National Geographic Kids Chapters: Danger on the Mountain: True Stories of Extreme Adventures!

Copyright © 2016 National Geographic Partners, LLC

All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

Since 1888, the National Geographic Society has funded more than 12,000 research, exploration, and preservation projects around the world. The Society receives funds from National Geographic Partners LLC, funded in part by your purchase. A portion of the proceeds from this book supports this vital work. To learn more, visit www.natgeo.com/info.

For more information, visit www.nationalgeographic.com, call 1-800-647-5463, or write to the following address:

National Geographic Partners

1145 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 U.S.A.

Visit us online at nationalgeographic.com/books

For librarians and teachers: ngchildrensbooks.org

More for kids from National Geographic: kids.nationalgeographic.com

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights: ngbookrights@ngs.org

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC and Yellow Border Design are trademarks of the National Geographic Society, used under license.

Art directed by Sanjida Rashid

Designed by Ruth Ann Thompson

National Geographic supports K–12 educators with ELA Common Core Resources. Visit natgeoed.org/commoncore for more information.

Trade paperback

ISBN: 978-1-4263-2565-6

Reinforced library edition

ISBN: 978-1-4263-2566-3

eBook ISBN: 978-1-4263-2568-7

v3.1

Version: 2017-08-29

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

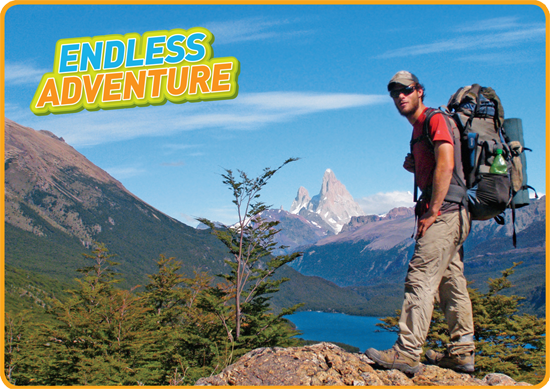

ENDLESS ADVENTURE

Chapter 1: Out of Control

Chapter 2: Pushing Boundaries

Chapter 3: Wild for Wolverines

THREE SECONDS OF COURAGE

Chapter 1: One Foot in Front of the Other

Chapter 2: Painful Lessons

Chapter 3: Moose on the Loose

DANGER ON THE MOUNTAIN!

Chapter 1: Walking on Clouds

Chapter 2: Chilly in Chile

Chapter 3: Beautiful Puzzle

DON’T MISS!

More Information

Credits

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Author’s Note

Explorer Gregg Treinish enjoys the view from the top of a mountain. (Photo Credit p1.1)

Skittish horses kick up dirt in their corral. (Photo Credit p1.1.1)

The pounding of horses’ hooves was like thunder in my ears. I knew I was in trouble when the frothy white foam from my horse’s mouth flew back and hit me in the face. I clung to his sweaty neck as he sprinted. I felt completely out of control.

This had all been my dad’s idea. My family was on a six-week, cross-country trip out West. My dad had been talking about doing this trip my whole life. When we left the Ohio, U.S.A., suburbs, I had no idea what was ahead, but I couldn’t wait. I loved the idea of journeying into the unknown.

So far, the trip had been amazing. We had searched for grizzly bears in Yellowstone National Park. We had raced go-karts in Wisconsin, visited Mount Rushmore in South Dakota, and hiked in the Grand Canyon in Arizona. Now we were in Nevada.

On this day, my dad wanted to take my brothers and me horseback riding in the foothills of the gigantic, snow-capped Sierra Nevada mountains.

I followed my brothers out of the RV and headed toward a dusty, run-down barn. But my excitement turned into something else as soon as I saw the horses.

Did You Know?

Yellowstone National Park is an animal-lover’s dream. It’s home to 67 species of mammals, 285 bird species, and 6 kinds of reptiles.

Right away, I could tell that the horses weren’t well cared for. They were dirty and skittish. They tossed their heads as if they were afraid.

The man getting the horses ready dropped heavy western saddles on their backs. The horses sidestepped and snorted. He yelled at them to stand still while he tightened the saddles to keep them from slipping. We mounted up. But the horses wouldn’t move.

The man smacked them to make them walk out of the corral. I had a sick feeling in my stomach for the animals.

But once we left the corral, I started to feel something else. I loved the powerful feeling of riding a horse. My body fell into a rhythm with the horse’s motion as he walked forward. I gripped the cracked leather reins that rested across his neck, and I looked out toward the mountains. I took a deep breath and closed my eyes for a moment.

As soon as we got away from the barn, my horse threw his head up and walked faster through the lush prairie. The other horses walked a little faster, too. I wondered if the horses had planned an escape.

Did You Know?

A horse can run about the same speed cars drive—25 to 30 miles an hour (40.2 to 48.2 km/h).

Then my horse leaped forward. I lurched back. Now we were trotting, one-two, one-two, one-two, faster and faster. I bounced hard with each quick step and yelled for him to stop.

But the horse didn’t stop. He lowered his head and charged across the meadow like a runaway train. I held my breath and struggled to balance as the horse plunged forward. We skimmed over rocks and wove around bushes and logs. I dug my fingers into his tangled mane as I clung to his neck.

The other horses raced, too. My dad held on to my little brother David’s shirt as he dangled off the side of the horse they shared. David screamed and cried.

Eventually, the horses got tired. Somehow, we got back to the barn without falling off or killing ourselves.

My brothers and my dad got off and said they never wanted to ride horses again. But I loved the rush of tearing across that open range. I also really, really wished I could have helped those horses. I could feel their misery. This crazy ride left a strong impression on me as a kid.

Today, I’m a biologist (sounds like bye-OL-uh-jist). Ever since I was a kid, I have loved outdoor adventure. And I’ve always wanted to make a positive impact on the world.

I founded an organization called Adventure Scientists. We match extreme outdoor athletes (like hikers, paddlers, and skiers) with information-hungry scientists who need data samples from hard-to-reach places all over the world.

(Photo Credit p1.1.2)

I once hiked for 520 miles (837 km) in the Northern Rocky Mountains to study wild animals like wolverines, moose, mountain lions, and grizzly bears. I collected information to help protect those species and their wild homes, but I also became part of the ecosystem (sounds like EE-koh-sis-tum) myself. If you see a wild animal, you can think like a biologist, too. Imagine yourself as the animal. View the world from the animal’s eyes. Ask yourself questions about how the animal might act or how it finds food.

Even though I grew up in the suburbs, I saw beauty in nature and animals all around me. I had a few wild “pets” at home, like the chipmunk that lived under our garage. I called him Chippy.

I loved Chippy. I’d sit and wait for him to show up. Then I’d watch him run around. There was a stray cat I used to watch for, too. I called him Mr. Whiskers.

Looking back, I realize it was my connection with animals that started me on the path to become a biologist, and to start Adventure Scientists. As a kid, I thought a lot about how animals survived despite the challenges of their environments.

I had struggles in my own environment, too. I got in trouble a lot. That summer of our trip out West, I spent a lot of time in the bathroom of the RV. That’s where my parents made me sit if I was harassing my brothers too much.

I saw a lot of Yellowstone National Park through the bathroom window, including animals like bison, elk, and eagles. I really wanted to see a grizzly bear on that trip, but we never did.

When I got back home and started the eighth grade, life was hard then, too. I made fun of other kids. As a result, I didn’t have many friends. I was usually the kid people’s parents didn’t want their kid to be friends with. That made school tough.

But outdoors, things were different. I always felt more comfortable outdoors than indoors. So I became an explorer.

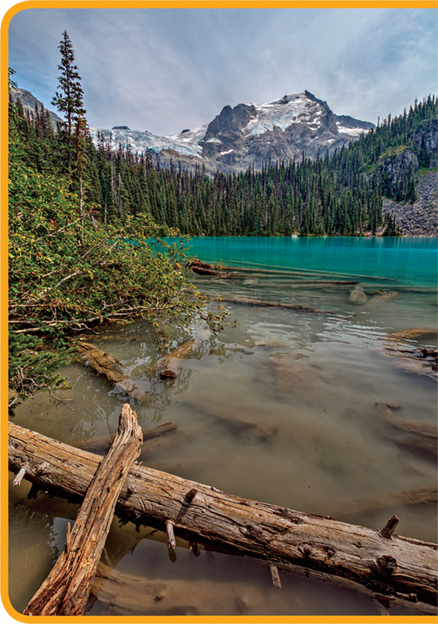

The pristine wilderness awaited Gregg in Garibaldi Park, north of Vancouver. (Photo Credit p1.2.1)

I could hardly hear anything except my own heavy breathing as I struggled up the steep ridge trail. My pulse throbbed in my ears. To make it to the top, I focused on a single tree up ahead. Ten more steps to reach it. Then I’d pick another towering pine tree and make a goal to reach that.

I was 16 now. Dealing with other kids at school had gotten harder for me. I tried to stay out of trouble, but it never seemed to work. I didn’t want to follow the rules. I pushed boundaries with my parents and my teachers.

My grandma Mandu seemed to sense that an outdoor adventure might help me. She offered to send me on a guided, three-week summer wilderness trek on the coast of British Columbia, Canada. I couldn’t wait to go. But once I was there, I was having a tough time. It was hard.

The rocky trail stretched out long and steep in front of us. We were in Garibaldi Park, a pristine wilderness north of Vancouver, Canada. I tried not to think about the weight of the pack on my back. Hardly anyone talked as our group slowly trudged up the hill.

The kid in front of me was slow. He kept stumbling and crying and holding up the group. We could only go as fast as our slowest member. I was getting upset with him.

Did You Know?

Garibaldi Park is home to mountain goats, grizzly bears, bald eagles, and endangered trumpeter swans.

Then he fell. Our guide, Guybe (sounds like GUY-bee) was quick to help. Guybe asked us to divide up the stuff in the kid’s pack and help him carry it. It had never occurred to me to offer to help. But I realized that was the quickest way to get to the top. I knew I was strong enough to carry a little more.

Guybe unzipped the kid’s pack. I reached in and grabbed a five-pound (2.3-kg) bag of apples and put it in my own pack. I carried it the rest of the day. Helping was a new thing for me. I was part of a team. I was doing something right. For once, I was not in trouble. That was a big deal.

I admired Guybe. He seemed fearless. He also had a lot of wilderness experience. Guybe had been a thru-hiker on the Appalachian (sounds like ap-uh-LAY-chun) Trail. That means he had walked the whole 2,190 miles (3,524 km) from Georgia to Maine, U.S.A.

Guybe and I talked a lot about long hikes. He told me he thought I could do a hike like the Appalachian Trail. I wasn’t so sure. Maybe I could do the Buckeye Trail. That’s the long-distance trail that loops around my home state of Ohio. That might be something I could do. But I wasn’t so sure I could do anything quite like Guybe did. To me, he was a mythical creature.

(Photo Credit p1.2.2)

Once during that three-week summer trek, he helped our whole group get through a scary situation. The trail had washed out after a storm. Thinking there was no way to get across, we stopped short. To our left was a wall of dirt and rocks that spilled across where the trail had been. To the right, the earth dropped off. I didn’t see how we could get around it.

Guybe skipped across the loose, wet rocks in his sandals. Then he looked back and told us “c’mon,” like it was nothing.

(Photo Credit p1.2.3)

A friend of mine refers to hiking as “land snorkeling.” You can see a lot when you’re on foot. When you walk through the woods—as opposed to driving or being on a bike—you notice everything. You see animals moving through the shadows. You see the bark on the trees. I always tell people to “hike their own hike.” Go where you want to go. Stop when you want to stop. And take your time as you land snorkel through the woods.

A couple of kids made it across the 10-foot (3-m) gash in the trail. But when it was my turn, I looked over the edge to the right. Roots dangled out from the side of the hill. Sharp rocks were piled a long way down below. My heart pounded. My feet wouldn’t move.

Guybe looked at me. “You can do it,” he said, “just go fast.”

I took a deep breath and launched. I went fast. The rocks skittered under my feet. I slipped and stumbled and went down on one knee. I heard the smash of a rock as it sailed over the edge and landed against another rock down below. I couldn’t believe I wasn’t dead yet.

Guybe had a way of making me believe in myself. I focused on his calm voice. I got up. I kept going. It all happened kind of fast. Suddenly, I was on the other side. I was terrified! But I was also laughing and talking with the other kids about the crossing. It was like pushing a boundary in a different kind of way. I had pushed myself.

Another time on that trip, we paddled sea kayaks around an unpopulated island off the coast of Vancouver. When a summer storm rolled in, I felt like I was paddling through a cloud. There was so much rain and mist that I couldn’t see a thing. I was cold and wet and had no idea where I was going. But I had trust in my guide, and I was gaining trust in myself.

Did You Know?

Early Arctic nomads hunted in hand-carved sea kayaks.

(Photo Credit p1.2.4)

After our group paddled to shore, climbed out onto the beach, and secured our stuff, Guybe taught us how to build a sauna on the beach. It was a fun way to get warm. We dragged branches and logs in from the woods. We set them up and built a teepee with a tarp. Then we built a fire inside it and put rocks on the fire. When the rocks got hot, we poured salt water on them. Warm steam filled our makeshift teepee. I breathed in the warm, salty air, feeling tired but strong and resourceful.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги