National Geographic Kids Chapters: Diving With Sharks!: And More True Stories of Extreme Adventures!

Copyright © 2016 National Geographic Partners, LLC

All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

Since 1888, the National Geographic Society has funded more than 12,000 research, exploration, and preservation projects around the world. The Society receives funds from National Geographic Partners, LLC, funded in part by your purchase. A portion of the proceeds from this book supports this vital work. To learn more, visit www.natgeo.com/info.

For more information, please visit www.nationalgeographic.com, call 1-800-647-5463, or write to the following address:

National Geographic Partners

1145 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 U.S.A.

Visit us online at www.nationalgeographic.com/books

For librarians and teachers: www.ngchildrensbooks.org

National Geographic supports K–12 educators with ELA Common Core Resources. Visit natgeoed.org/commoncore for more information.

More for kids from National Geographic: kids.nationalgeographic.com

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights: ngbookrights@ngs.org

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC and Yellow Border Design are trademarks of the National Geographic Society, used under license.

Art directed by Callie Broaddus

Designed by Ruth Ann Thompson

Trade paperback

ISBN: 978-1-4263-2461-1

Reinforced library edition

ISBN: 978-1-4263-2462-8

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-4263-2463-5

v3.1

Version: 2017-07-11

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

DAVID DOUBILET AND JENNIFER HAYES: Diving With Sharks!

Chapter 1: Face-to-Face

Chapter 2: Swimming With Seals

Chapter 3: Great White Bite

RHIAN WALLER: Keeping Your Cool!

Chapter 1: Cold Conditions

Chapter 2: Danger in the Dark

Chapter 3: Running Out of Air

KENNY BROAD: Into the Dark!

Chapter 1: Diving Deep

Chapter 2: Deadly Depths

Chapter 3: A Surprising Find

DON’T MISS!

More Information

Credits

Dedication

Acknowledgments

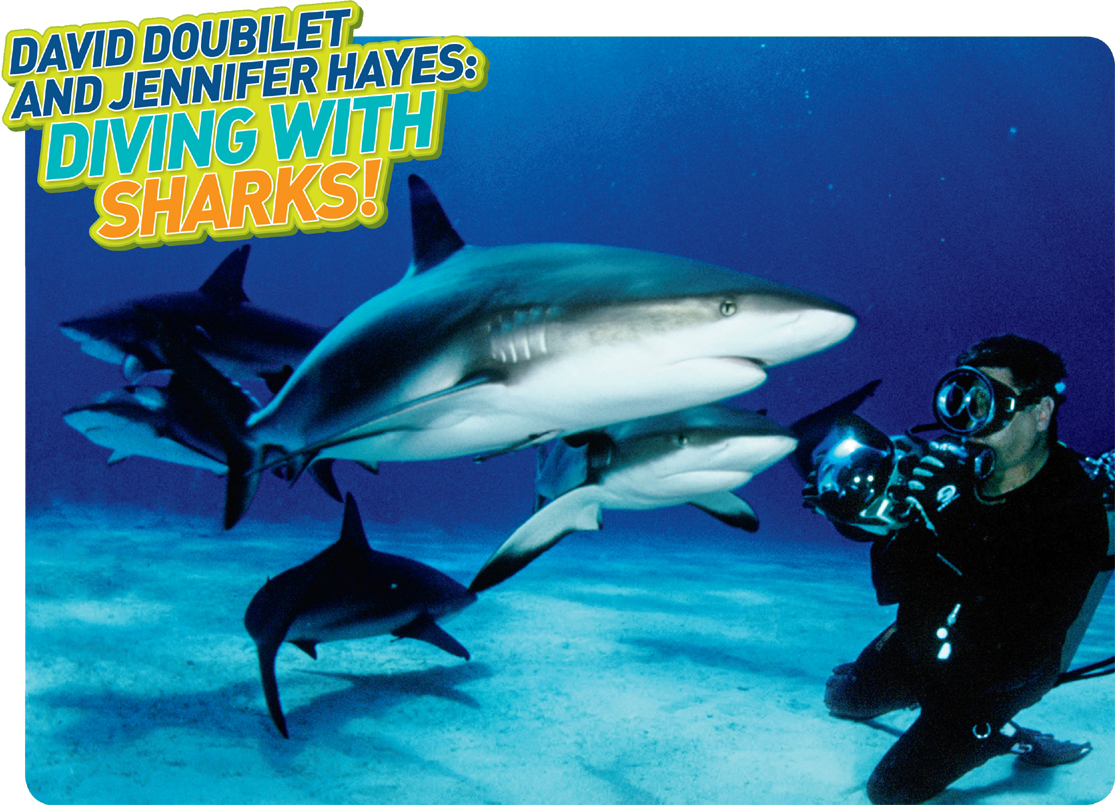

Photographer David Doubilet comes face-to-face with some Caribbean reef sharks. (Photo Credit p1.1)

A tiger shark feeds on a dead sperm whale. (Photo Credit p1.1.1)

The radio on the boat crackled to life. David Doubilet and his wife and diving partner, Jennifer Hayes, listened closely. A dead sperm whale had been sighted off the reef of Cairns in Australia. This was rare. There had not been a sperm whale carcass sighting in 30 years. Ten large tiger sharks were feeding on the whale. David knew they had to photograph it.

It’s unusual to see sharks feeding in the wild. Sometimes sharks are hand-fed during tours so tourists can dive and see them. David and Jennifer knew that this natural feeding would be a special opportunity.

They set the boat’s coordinates (sounds like co-ORE-din-its) to where the whale had been spotted, and sped along the water as fast as they could. Yet when they arrived at their destination, there was no whale to be seen. The wind and tide had moved it, but where?

David and Jennifer scanned the water. Finally, they saw a large mass floating on the ocean’s surface. They breathed a sigh of relief. It was the whale.

The whale’s white flesh was oozing whale oil. The strong smell filled the air. And eight large tiger sharks circled the carcass. It was time for David and Jennifer to get a closer look.

David and Jennifer slipped into the water. From there, they had a much better view. The sharks’ teeth ripped into the whale’s body, tearing it to shreds. David and Jennifer raised their cameras and began taking pictures.

Did You Know?

Sharks are ancient animals. The first one lived on Earth about 400–450 million years ago.

They knew that as long as they kept their distance from the sharks, they’d be safe. After all, the sharks were busy eating the whale. But they had taken some precautions (sounds like pree-COSH-ens), just in case. Both were wearing full diving gear. “We always wear full wet suits, including gloves that cover our hands,” said Jennifer. “Our bare hands look a lot like dead fish and may be tempting to a shark used to seeing dead fish as food.” They also had their cameras. In some ways, those big cameras helped the team feel safer. It was like having an extra layer of protection between them and the sharks.

So, David and Jennifer focused on shooting pictures. The sharks focused on their meal. In fact, the sharks didn’t seem to notice David and Jennifer at all.

But as they kept taking pictures, David and Jennifer didn’t realize they were getting closer and closer to the tiger sharks and their carcass. The sharks noticed, though. Suddenly, the mood changed. The sharks were interested in the two humans bobbing in the water.

David and Jennifer looked around. They had somehow drifted too close to the whale. Now, the sharks saw them as a threat. Finding food in the ocean can be hard, and sharks will protect their meal. David and Jennifer weren’t safe anymore.

The sharks began to circle. They swam close enough to bump into David and Jennifer. That’s when the photographers thought about their “extra layer of protection.” They held their cameras in front of them to block the sharks.

Suddenly, one of the sharks lunged forward. It bit at one of the large, round strobe lights attached to the cameras. Other sharks did the same.

(Photo Credit p1.1.2)

David and Jennifer are married, and they work together, too! On land, they have different jobs. David prepares their camera gear and lights. Jennifer researches their subjects and talks with experts. Underwater, they work as a team. To make sure they understand each other underwater, they use hand signals. Or they write using a dive slate and pencil. In dangerous situations, David and Jennifer wear face masks with voice gear so they can talk to each other—that’s the clearest form of communication.

Strobes are normally used to light up dark areas. But now they were being used as shark shields!

David and Jennifer needed a way to fend off the sharks until they could swim to safety. They changed their position in the water and put their backs against each other. This way they could see all around them. They could see where the sharks were. That would keep them safe.

They began to swim slowly away from the sharks and toward their boat. The key was to keep their movements small. If they moved too quickly, the sharks would react.

Soon, they put space between themselves and the sharks. That seemed to work. No longer thinking someone was after their food, the sharks headed back toward the whale to finish their meal.

The danger had passed. David and Jennifer shook off the scary encounter. They raised their cameras again to take more photos.

The sun was beginning to set. Dawn and dusk are prime feeding times for sharks. The water was full of the smell of whale oil. That smell brought more tiger sharks to the whale.

David and Jennifer were still in the water taking pictures. But they and their gear were now covered in whale oil.

“Our rubber suits sucked up and absorbed all the whale oil,” said Jennifer. “We smelled like food. Like wounded fish.”

The tiger sharks were still hungry. Before long, they surrounded David and Jennifer. The sharks made fast runs toward them, bumping and nudging them. David and Jennifer looked to their boat. So did the sharks. The boat was also covered in whale oil. And like the whale, the boat was white.

“It was time to get out before things got out of control,” said Jennifer. David and Jennifer swam as fast as they could. The sharks followed. Reaching the boat didn’t mean they were safe, though. The sharks tried to bite the boat. David and Jennifer put the boat into gear and motored away as fast as they could.

Jennifer Hayes took this picture of a mother harp seal nuzzling her baby. (Photo Credit p1.2.1)

The water temperature in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence was below freezing, but diver, scientist, and photographer Jennifer Hayes hardly noticed. She had thick, warm clothes under her dry suit. She wore special dry gloves and boots attached to her suit. These items were made to keep her warm. What Jennifer didn’t know was that they would save her life on this dive.

Jennifer was snorkeling alone this time, without her husband, David Doubilet. Her goal was to take photos of a baby harp seal and its mother. But that was a challenging assignment (sounds like ah-SINE-ment) because mother and pup harp seals don’t stay together long. After a harp seal is born, its mother nurses it for between 12 and 15 days. Then the mother leaves her pup to survive on its own.

Jennifer jumped into the icy waters in search of a mother and her pup. Before long, she spotted a baby seal on top of a sheet of frozen ice, or ice floe (sounds like FLO).

Just as Jennifer approached the pup, its mother swooped past Jennifer and swam toward her pup. Jennifer watched as the pup and mom met underwater. They rubbed noses. “It was a kiss of recognition,” said Jennifer. She captured the tender moment with her camera before the mom led her pup away.

Jennifer wanted more photos of the mom and pup together. As the seals swam toward another ice floe, Jennifer swam alongside them. The pup kept swimming toward her. He seemed interested. But each time the pup got too close, his mom would push him back with her flipper.

Did You Know?

By day 15, harp seals can reach 80 pounds (36.3 kg). However, after their mothers leave them, they can lose more than half of that weight before they figure out how to survive on their own.

Yet the baby seal was determined. As the seals and Jennifer swam through the ice, the pup came closer and closer to Jennifer. When Jennifer and the seals stopped to rest, the pup climbed onto Jennifer’s arm. Jennifer floated on her back, and the pup pushed himself onto her chest. Jennifer couldn’t believe she was so close to the pup. She clicked away with her camera. Finally, the pup rolled off her chest. His mom swam over and inspected him, making sure he was okay.

Jennifer floated in the water, watching the seals, when she suddenly felt a nip on her right ankle. Then she felt another bite on her left ankle. What was going on?

“I looked down and saw more than 20 male harp seals circling below me,” said Jennifer. She took a picture of them. She wasn’t worried. She remembered her guide’s warning when she was learning to dive: Sometimes the animals will test you.

Her thought was cut short, though, as a 400-pound (181-kg) male seal suddenly climbed onto her back and over her head. He pushed her completely underwater and knocked off her mask.

The uncertainty of what could happen next concerned Jennifer. Would the harp seal attack her again? Jennifer grabbed her mask and tried to put it back on her face. Then another blur zoomed past her.

But this blur wasn’t after Jennifer. It was the mother harp seal, and she was after the male. The mother seal dived down and slammed into the male seal. Jennifer saw a jumble of fur and flippers as the mother harp seal battled the male seal. Jennifer and the pup floated above the mother and male, watching and waiting.

(Photo Credit p1.2.2)

Think you have what it takes to be a diver like David and Jennifer? You can start by watching the animals you want to study. Learn about their habits from the Internet, books, or visiting them in an aquarium. Learn to swim or snorkel. Then bring your camera and practice taking pictures of animals from a safe distance away. Don’t be afraid to ask an expert’s advice. And be patient. David and Jennifer sometimes wait for hours to get that perfect shot.

Finally, the mother resurfaced. She grunted as she swam toward her pup. She inspected her pup. She nudged him through the water with her head and flippers.

When the mother was sure her pup wasn’t hurt, she swam to Jennifer. This surprised Jennifer. She couldn’t believe the mother seal seemed to care about her, too. “She began to nudge me like she did her pup, until I was next to him,” said Jennifer.

Then the mother began to move the pair through the water, away from the male seals below them. There was a small gap in the ice. The mother and pup slipped into the gap and disappeared. Jennifer watched them go.

Jennifer swam to the edge of the ice and began taking off her weight belt and camera. But before she could finish, she felt a sharp pain on her leg. The male harp seal had returned.

He bit Jennifer again on her thigh. The bite was deep. She knew she had to make it out of the water and onto the ice. If she didn’t, the results could be deadly. “He could have pulled me underneath the sheet of ice that went on for hundreds and hundreds of feet,” said Jennifer. “I would have been stuck under the ice.”

Jennifer jumped onto the ice floe. She could stand on the ice, but it hurt to walk far. Her right leg felt weak, and there were puncture wounds in her dry suit, but there was no gushing blood. “I thought it might not be so bad,” she said. But she needed to be sure. Back on her boat, she inspected her leg. The bite was long but not bleeding too badly. It hurt, but it wasn’t a life-and-death situation (sounds like sit-yoo-A-shun).

More than two years later, Jennifer still has the scars and the memories. “The suit saved my life,” she said. If the suit hadn’t been made of tough Kevlar, the seal might have broken through it. Her injuries could have been much worse.

But that frightening moment is not what she focuses on. Instead, she’s in awe of the mother seal and how she protected Jennifer. “Had someone else told this story to me, I wouldn’t have believed them. I’m less of a skeptic now. Animals do amazing things, and there’s no answer why,” she said.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги