National Geographic Kids Chapters: Rhino Rescue: And More True Stories of Saving Animals

Copyright © 2016 National Geographic Society

All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

Staff for This Book

Shelby Alinsky, Project Editor

Callie Broaddus, Art Director

Ruth Ann Thompson, Designer

Bri Bertoia, Photo Editor

Brenna Maloney, Editor

Paige Towler, Editorial Assistant

Rachel Kenny and Sanjida Rashid, Design Production Assistants

Tammi Colleary-Loach, Rights Clearance Manager

Michael Cassady and Mari Robinson, Rights Clearance Specialists

Grace Hill, Managing Editor

Alix Inchausti, Production Editor

Lewis R. Bassford, Production Manager

George Bounelis, Manager, Production Services

Susan Borke, Legal and Business Affairs

Published by the National Geographic Society

Gary E. Knell, President and CEO

John M. Fahey, Chairman of the Board

Melina Gerosa Bellows, Chief Education Officer

Declan Moore, Chief Media Officer

Hector Sierra, Senior Vice President and General Manager, Book Division

Senior Management Team, Kids Publishing and Media Nancy Laties Feresten, Senior Vice President; Erica Green, Vice President, Editorial Director, Kids Books; Amanda Larsen, Design Director, Kids Books; Julie Vosburgh Agnone, Vice President, Operations; Jennifer Emmett, Vice President, Content; Michelle Sullivan, Vice President, Video and Digital Initiatives; Eva Absher-Schantz, Vice President, Visual Identity; Rachel Buchholz, Editor and Vice President, NG Kids magazine; Jay Sumner, Photo Director; Amanda Larsen, Design Director, Kids Books; Hannah August, Marketing Director; R. Gary Colbert, Production Director

Digital Laura Goertzel, Manager; Sara Zeglin, Senior Producer; Bianca Bowman, Assistant Producer; Natalie Jones, Senior Product Manager

The National Geographic Society is one of the world’s largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations. Founded in 1888 to “increase and diffuse geographic knowledge,” the Society’s mission is to inspire people to care about the planet. It reaches more than 400 million people worldwide each month through its official journal, National Geographic, and other magazines; National Geographic Channel; television documentaries; music; radio; films; books; DVDs; maps; exhibitions; live events; school publishing programs; interactive media; and merchandise. National Geographic has funded more than 10,000 scientific research, conservation, and exploration projects and supports an education program promoting geographic literacy.

For more information, please visit nationalgeographic.com, call 1-800-NGS LINE (647-5463), or write to the following address:

National Geographic Society

1145 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 U.S.A.

Visit us online at nationalgeographic.com/books

For librarians and teachers: ngchildrensbooks.org

National Geographic supports K–12 educators with ELA Common Core Resources. Visit natgeoed.org/commoncore for more information.

More for kids from National Geographic: kids.nationalgeographic.com

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights: ngbookrights@ngs.org

Trade paperback

ISBN: 978-1-4263-2311-9

eBook ISBN: 978-1-4263-2313-3

Reinforced library edition

ISBN: 978-1-4263-2312-6

v3.1

Version: 2017-07-11

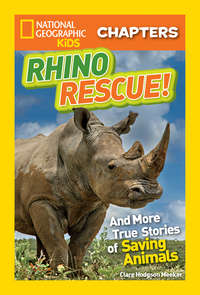

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

HONEY GIRL: Miraculous Monk Seal!

Chapter 1: Hooked

Chapter 2: A Delicate Operation

Chapter 3: Miracle Mom

KUZYA AND BORYA: Tiger Rescue!

Chapter 1: Brothers in Trouble

Chapter 2: Practice Makes Purrfect

Chapter 3: Home Free

KASS AND DRAEGON: Rhino Rescue!

Chapter 1: Thinking Big

Chapter 2: Flying on Their Feet

Chapter 3: Running Free

DON’T MISS!

More Information

Credits

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Honey Girl, a Hawaiian monk seal, looks back before diving into the ocean.

(photo credit p1.1)

Having “hauled out” on a sandy beach in Hawaii, this female monk seal warms herself in the sun.

(photo credit 1.1)

November 2012

Oahu, Hawaii

A kite surfer squinted into the sun. The waves were pretty good that day off the northeastern coast of Oahu (sounds like oh-WAH-hoo) in Hawaii. Suddenly, something caught his eye. There, bobbing in the waves just ahead of him, was a strange sight.

It looked like a monk seal. But this monk seal was green. And it wasn’t moving. It looked like the seal was tangled up in something. The surfer wasn’t sure what was going on, but one thing was clear: This seal was in trouble.

Did You Know?

Hawaiian monk seals get their name from the soft folds of fur around their necks. People used to think these folds looked like the hood on a monk’s robe.

When the surfer reached land, the first thing he did was call the Hawaiian monk seal hotline. The hotline is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries Service. He described what he’d seen to wildlife biologist Tracy Mercer. Tracy is in charge of NOAA’s monk seal search and rescue operations on the main Hawaiian Islands. Since 2002, she’s been working with a team of NOAA scientists, staff, and volunteers to keep track of this endangered population of Hawaiian monk seals. The team also rescues injured seals so they can be treated and returned to the wild. Tracy sent a search team to the spot where the surfer had seen the seal. They found nothing.

Five days later, a NOAA response team volunteer sent photos of a monk seal lying on a beach not far from where the injured seal had first been spotted. The seal was dangerously thin, and it looked green.

Tracy studied the photo. Her heart sank as she read the tag on the monk seal’s flipper: R5AY. She knew this seal. It was Honey Girl, a 17-year-old female. Honey Girl was well known to the NOAA staff and volunteers.

(photo credit 1.2)

Monk seals are native to Hawaii. They aren’t found anywhere else in the world. The northeastern coast of Oahu is known for its big waves and rough water. When storms roll in from the Pacific Ocean, most animals take cover. But the monk seal is built for this rugged environment. It has a sleek, barrel-shaped body and powerful back flippers. It can glide through strong ocean currents and dive deep for food. Ancient Hawaiian legends called the monk seal Ilio holo i ka uaua (sounds like EE-lee-oh HO-lo i COW ah-OO-ah). It means “the dog that runs in rough seas.”

Honey Girl had given birth to seven pups over seven years. Everyone called her a “miracle mom.” She had raised each pup with great care. Now Honey Girl was the one in need of care. Tracy knew she had to save her. She also knew she’d need help to do it.

NOAA’s on-duty marine mammal veterinarian (sounds like vet-er-ih-NAIR-ee-en) answered the call. Dr. Michelle Barbieri (sounds like bar-bee-AIR-ee) knew a lot about monk seals. At first light, she and Tracy began the long drive to the coast. Hours later, they reached the beach and started their search.

Over the next three days, Tracy, Michelle, and a team of volunteers hiked along a 15-mile (24-km) stretch of coastline, searching. Monk seals spend most of their time in the water, but a healthy seal will spend time on land, too. It’s called “hauling out.” The team combed the beaches, hoping to find Honey Girl.

Finally, they saw her. She was drifting in the waves offshore. But she was never close enough to the shore for them to reach her. Tracy and Michelle grew anxious (sounds like ANGK-shuhs). “It’s suspicious when a monk seal does not haul out and is floating or logging on the water’s surface,” said Michelle. “Maybe something is preventing her from coming on shore.” But what could it be?

They got their answer when they found Honey Girl on the beach a few days later, asleep. “We didn’t want to scare her back into the water,” said Michelle. As they approached her quietly, they saw the source of Honey Girl’s problem.

A fishhook the size of Michelle’s palm was lodged into Honey Girl’s cheek. A tangle of razor-sharp fishing line trailed from her mouth. Every time she moved, the line cut deeper into her skin.

Finding Honey Girl solved another mystery, too. Tracy and Michelle discovered why Honey Girl looked green. Her coat was covered with mossy, green algae (sounds like AL-jee).

“Algae grows on most seal hair, but it usually bleaches out from their lying in the sun,” said Michelle. “Honey Girl must have been floating in the water for several weeks.” The sun hadn’t bleached it.

Michelle noticed something else, too. Honey Girl’s ribs and spine were showing. This meant she had not eaten for a very long time.

This worried Michelle. She knew that Honey Girl had recently weaned a pup. She had already lost half of her body weight from nursing her pup. She needed to eat to regain that weight.

It was clear that Honey Girl needed immediate help. There was no way to tell at that moment how much damage the fishing line had done. At least Michelle could trim away some of the line to make things less painful for Honey Girl.

Michelle and Tracy decided to transport Honey Girl to the Waikiki (sounds like WHY-kee-kee) Aquarium. It was the only place on Oahu that treated injured marine mammals.

Honey Girl was hurt, but she was also probably pretty scared, too. The rescue team needed to move carefully but quickly.

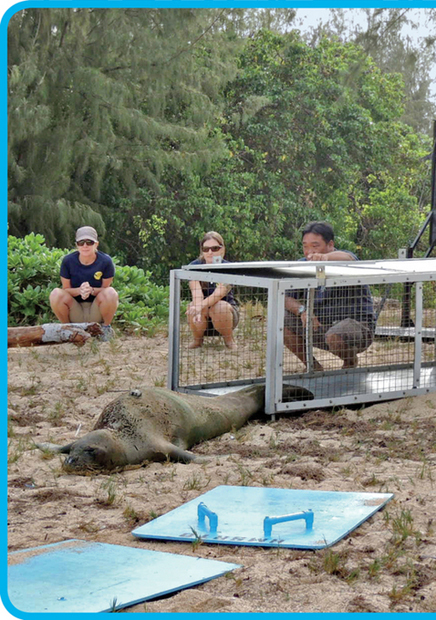

Moving an injured monk seal is a tough challenge. Even at half her normal weight, Honey Girl weighed more than 300 pounds (136 kg). The team used a large plank of wood with a handle on the back to gently guide her into a metal cage.

Once Honey Girl was inside the cage, it took six people to lift it onto the back of a truck. Honey Girl opened her eyes but showed little reaction to the people around her. As the truck drove off, everyone was wondering if Honey Girl would make it. Would she ever see the ocean again?

Rescuers watch as Honey Girl wriggles out of a carrying cage and makes her way back to the ocean.

(photo credit 2.1)

At the Waikiki Aquarium, Honey Girl was given medicine to make her feel drowsy. Only now was it safe for Michelle to gently open her mouth and look inside. The fishing line had left her tongue swollen and deeply infected. It was hard to know how far the infection had spread. Honey Girl would need surgery to repair the damage.

Performing surgery on any wild animal can be dangerous. It’s especially hard on a monk seal. The same dive reflex that allows a seal to stay underwater for a long time could cause her to stop breathing when she’s put to sleep for surgery. Michelle needed an experienced doctor. She called on Dr. Miles Yoshioka at the Honolulu Zoo. He agreed to take the job.

Miles took a look at Honey Girl. The infection had not spread beyond her tongue. That was the good news. But much of her tongue was damaged beyond repair. Miles had to cut away nearly two-thirds of Honey Girl’s tongue. The next few days after the surgery would be critical. No one knew if Honey Girl would survive.

Honey Girl was moved to an empty pool to recover. For two days after the surgery, she barely moved at all. Michelle didn’t know if Honey Girl was ready to swim yet, so they kept the tank empty of water.

Honey Girl was weak and dehydrated. Michelle injected fluids under her skin to rehydrate her. She gave her more pain medication to soothe her swollen tongue. None of these treatments seemed to help.

On the third day, Michelle filled the empty pool with water. As soon as the water was high enough for her to float, Honey Girl started swimming. Michelle and the aquarium staff were thrilled to see her moving again. But Michelle was also cautious (sounds like CAW-shus). She knew Honey Girl was weak. She made sure that a staff member was always nearby, in case Honey Girl struggled in the water or started to sink.

But instead of showing signs of weakness, Honey Girl seemed to grow stronger in the water. She also tried to bite her caretakers with her sharp teeth. This was a very good sign. It meant that Honey Girl was responding the way a wild animal should when near humans.

Now they needed Honey Girl to start eating again to gain back her strength. Michelle used a tube to feed Honey Girl a meal of pureed (sounds like pure-AID) herring and water. It was like drinking a fish smoothie!

The next day, Michelle put a small live fish in the pool. Honey Girl ignored it. She has to be hungry, thought Michelle. Is she in pain? Does it hurt to eat? Or maybe Honey Girl was just uncomfortable catching food with people around.

Unlike other seal species, monk seals spend most of their lives alone. The only time female monk seals gather in groups is when they are giving birth or nursing their pups. Since her rescue, Michelle had made sure that Honey Girl was never left alone. Maybe that’s what she needed now.

Thanksgiving had arrived. The aquarium staff members were eager to be home celebrating with their families. Michelle thought this would be a good day to test her idea and give Honey Girl some time alone. She put fresh fish in Honey Girl’s pool and hoped for the best.

(photo credit 2.2)

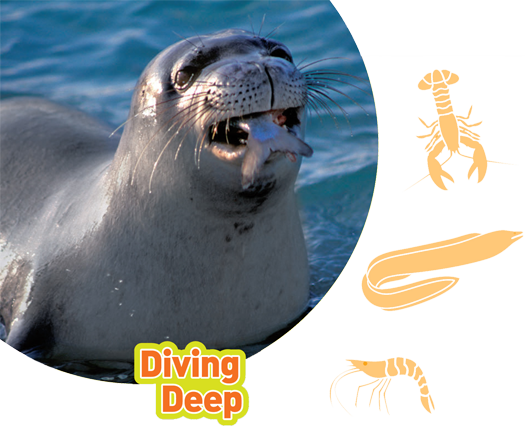

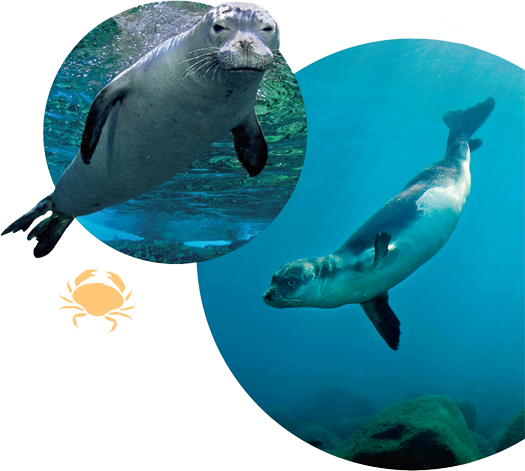

A Hawaiian monk seal eats a lot, but first it has to catch its meal. Monk seals can dive 1,500 feet (457 m) to hunt for food. Usually they make dives of less than 200 feet (61 m), though, to forage on the seafloor. A typical dive lasts about 6 minutes. On deeper dives, they can hold their breath for as long as 20 minutes.

(photo credit 2.3)

Monk seals aren’t picky eaters. They eat a variety of foods, depending on what they find. Squid, octopuses, eels, and many types of fish are all on the menu. They also eat crustaceans (sounds like kruh-STEY-shuns), like crabs, shrimp, and lobsters. A monk seal can eat up to 10 percent of its body weight in food each day.

Michelle spent the day at home with family. But she could not stop thinking about Honey Girl. Monk seals are not picky eaters. But would her injuries prevent her from eating even small fish?

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги