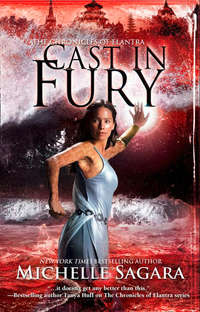

Cast In Fury

Добавить В библиотекуАвторизуйтесь, чтобы добавить

Добавить отзывДобавить цитату

Cast In Fury

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов

Авторизация