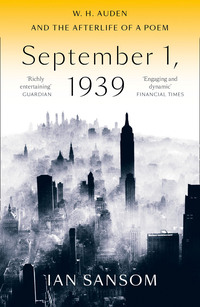

September 1, 1939

Whether we know it or not, we bring great expectations to a poem: we are conditioned to expect something from a poem, as soon as it declares itself a poem, and even more so when an ‘I’ declares itself at the beginning of a poem. A poetic ‘I’ implies a particular kind of poem, a lyric poem, the kind of poem we are familiar with from school, a poem which usually promises and delivers intense personal emotions presented in the first person. M. H. Abrams, who was one of those literary critics everyone used to read and now almost no one has heard of – the fate of all critics – defined the Romantic lyric poem as a meditation that ‘achieves an insight, faces up to a tragic loss, comes to a moral decision, or resolves an emotional problem’. This is the kind of poem we know what to do with.

So what are we going to get here, in ‘September 1, 1939’? An insight? A reckoning? A decision? A resolution?

*

In ‘September 1, 1939’ we get all of that, and more – which is exactly the trouble, and what Auden hated about the poem, which he described as ‘the most dishonest’ he had ever written.

*

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s just assume for a moment – as we naturally do – that the ‘I’ here is an unproblematic person, that the ‘I’ here is Auden.

Fine.

*

Who the hell is W. H. Auden?

The Modern Poet

‘It’s odd to be asked today what I saw in Auden,’ replied the American poet John Ashbery to a wet-behind-the-ears interviewer in 1980. ‘Forty years ago when I first began to read modern poetry no one would have asked – he was the modern poet.’

*

In his 1937 ‘Letter to W. H. Auden’, the poet Louis MacNeice addressed his friend, ‘Dear Wystan, I have to write you a letter in a great hurry and so it would be out of the question to try to assess your importance. I take it that you are important.’

*

He was more than important: he was an absolute star. In his book The Personal Principle (1944), the literary critic D. S. Savage claimed that during the 1930s Auden was ‘the centre of a cult’ and, in a telling phrase, described Auden’s position thus: ‘A new star had arisen, it seemed, in the English sky.’ John Berryman recalled that even in America ‘by 1935 … the Auden climate had set in strongly’. What Tom Driberg in the Daily Express called ‘awareness of Auden’ was everywhere: it affected things generally; as Boswell breathed the Johnsonian ‘oether’, so the 1930s breathed the air of Auden. When the London Mercury was published for the last time on the eve of the Second World War, Stephen Spender summed things up in an article titled ‘The Importance of W. H. Auden’: ‘Auden’s poetry is a phenomenon, the most remarkable in English verse of this decade.’

*

Now, to be clear: not everyone admired Auden. Some people despised him. Hugh MacDiarmid thought him a ‘complete wash-out’. Truman Capote, when asked what he thought of Auden’s poetry, replied, ‘Never meant nothin’ to me.’ (Though – note – even MacDiarmid, in his polemical autobiographical prose work Lucky Poet (1943), attempting to define ‘The Kind of Poetry I Want’, had to devote much of his time to defining ‘the kind of poetry I don’t want’, i.e. ‘the Auden–Spender–MacNeice school’.) The argument against Auden is certainly worth stating and goes something like this:

‘W. H. Auden is to blame for everything that went wrong with English poetry in the late twentieth century. Absurdly overpraised when young, he remained naive and immature both as a person and as a poet, his preciosities and youthful good looks becoming vile and monstrous. He was dictatorial in his approach and his opinions, imprisoned by his own intelligence, intellectually dishonest, irresponsible and incoherent, atrociously showy in diction and lexical range, technically ingenious rather than profound, pathetically at the mercy of contemporary cultural and political fashions and ideas, facetious, frivolous, self-praising, self-indulgent, vulgar and ultimately merely quaint: the ruined schoolboy; an example, indeed the ultimate example, the epitome, the exemplum, not of mastery but of Englishness metastasised. Auden undoubtedly thought he was it and the next big thing, when in fact he was It: the disease, the enemy, The Thing.’

*

This sort of argument has been thoroughly rehearsed down through the years by readers such as F. R. Leavis, and Randall Jarrell (during the hate phase of his love–hate relationship), and Philip Larkin (ditto), and Hugh MacDiarmid, and William Empson. One would perhaps expect all of them to complain – they were world-class complainers – but when someone like Seamus Heaney, that Seamus Heaney, the Seamus Heaney, a poet and critic with perfect manners, whose kindness and generosity knew almost no bounds, when even Seamus Heaney, in a review of Auden’s Collected Poems, writes dismissively of Auden’s ‘educated in-talk’ and of his tone ‘somewhere between camp and costive’, one might begin to think that there is indeed a serious case to be made against him. Maybe Auden was just a coterie poet; maybe he was just a flash in the pan; a poet merely of his class and his place and his time. William Empson has a poem, ‘Just a Smack at Auden’, which is certainly very funny, mocking Auden’s 1930s doom-mongering (‘Treason of the clerks, boys, curtains that descend, / Lights becoming darks, boys, waiting for the end’), but Heaney’s summation of Auden’s achievement as ‘a writer of perfect light verse’ is potentially more wounding.

(We may well return to the question of ‘light’ verse later. But an obvious question has to be, does great literature necessarily have to be ‘heavy’? Does it have to be serious and difficult? Does it have to be exhausting and challenging and exceptional? Does every book have to be a pick-axe breaking the frozen sea in our souls? Sometimes it’s nice – isn’t it? – to hear the sound of a swizzle stick tinkling away at the ice.)

*

Anyway, and nonetheless, and despite the quibbles and the doubts, it would be safe to say that in the 1930s, for those whom it affected, the Auden phenomenon was as disturbing as it was remarkable. The title of Geoffrey Grigson’s contribution to the special 1937 New Verse Auden double issue, ‘Auden as a Monster’, is indicative of the fear and excitement generated by Auden’s reputation. ‘Auden does not fit. Auden is no gentleman. Auden does not write, or exist, by any of the codes, by the Bloomsbury rules, by the Hampstead rules, by the Oxford, Cambridge, or the Russell Square rules,’ enthused Grigson; Auden’s poetry, he claimed, had a ‘monstrous’ quality. Other contributors to New Verse were similarly impressed by Auden’s peculiar strength and power: Edwin Muir described Auden’s imagination as ‘grotesque’; Frederic Prokosch described his talents as ‘immense’; Dylan Thomas described him as ‘wide and deep’; Bernard Spencer claimed that he ‘succeeds in brutalizing his thought and language’.

*

Auden was clearly regarded – as great writers often are by their contemporaries – as somehow superhuman, or rather subhuman, inhuman, freakish. (Stephen Spender, in his Journals, recalls being accused of making Auden ‘sound a bit inhuman’: ‘This did ring a bell,’ he writes, ‘because I remember when we were both young thinking of him as sui generis, not at all like other people and of an inhuman cleverness. I did not think of him as having ordinary human feelings.’)

*

(I tend to fall into this trap today, with writers I know and admire: they are just not, I think, like me. They are different; they are special; they are odd. Which is both true, as it happens, and entirely false.)

*

With its emphasis on Auden’s ‘monstrous’ qualities, his physicality, his animality, his otherness, the New Verse double issue inaugurated a significant theme in subsequent figurations of Auden. In numerous books, reviews, essays and poems, Auden is figured as a kind of predatory Übermensch, possessing great physical prowess and preternatural powers. The English poet Roy Fuller, for example, described him as a ‘legendary monster’, an ‘immense father-figure’,‘ransacking the past of his art’. The poet Patrick Kavanagh claimed that ‘a great poet is a monster who eats up everything. Shakespeare left nothing for those who came after him and it looks as if Auden is doing the same.’ Such language can’t help but admire as much as be appalled.

Auden is a hero.

Auden is a monster.

*

His intelligence was superlative and frightening. (He was ‘the greatest mind of the twentieth century’, according to the Russian poet Joseph Brodsky. ‘At one or another time there must be five or six supremely intelligent people on earth,’ writes Howard Moss in his book Minor Monuments. ‘Auden was one of them.’)

His appearance was outlandish. (‘I was struck by the massive head and body and these large, strong, pudgy hands, […] the fine eyes did not look at oneself or at any individual but directly at concepts,’ wrote the critic G. S. Fraser.)

And his troubled career was strangely exemplary. (Seamus Heaney’s decision to leave Northern Ireland and move to Wicklow in 1972, for example, was read by some critics as a symbolic gesture similar to Auden’s move to America in 1939.)

He was a creature to be feared as well as admired, an obstacle to be negotiated as well as an inspiration.

‘He set standards so lofty that I developed writer’s block,’ recalls the poet Harold Norse in his Memoirs of a Bastard Angel: A Fifty-Year Literary and Erotic Odyssey (1989).

Even now he remains a barrier. This book, for example: both blocked and enabled by Auden, a classic example of reading in abeyance, a testament to his posthumous power, and a confession and demonstration of my own lowly subaltern status and secondariness.

*

(My interest in Auden, like anyone’s interest in any poet, any writer or artist, any great figure who has achieved and excelled in a field in which one wishes oneself to achieve and excel, represents an expression of awe, and disappointment, and self-disgust – and goodness knows what other peculiar and murky impulse is lurking down among the dreck at the bottom of one’s psyche. My interest in Auden represents perhaps a desire, if not actually to be Auden, then at least to be identified with Auden. My grandfather used to sing a song, ‘Let me shake the hand that shook the hand of Sullivan’, referring to John L. Sullivan, the one-time world heavyweight champion. How much literary criticism, one wonders, is in fact a vain attempt to shake the hand of Sullivan? U & I is the title of the novelist Nicholson Baker’s book about his – non-existent – relationship with John Updike, for example. An alternative title for this effort might be A & I. But this implies an addition. Better: I − A?)

The continual cracking of your feet on the road makes a certain quantity of road come up into you.

(Flann O’Brien, The Third Policeman)

‘Biographers are invariably drawn to the writing of a biography out of some deep personal motive,’ according to Leon Edel, the biographer of Henry James. Freud’s famous criticism of biographers was that they are ‘fixated on their heroes in a quite special way’, and that they devote their energies to ‘a task of idealization, aimed at enrolling the great man among the class of their infantile models – at reviving in him, perhaps, the child’s idea of his father’.

I don’t think I am reviving in Auden an idea of the father. But it’s possible that I might be reviving in him an idea of the uncle. The kind of uncle I never had.

(Auden was, by all accounts, an excellent uncle. He sponsored war orphans to go to college. He supported the work of Dorothy Day’s homeless shelter for the Catholic Worker Movement. He did not stint in doing good.)

*

He was many things to many people. As every critic notes, Auden’s book The Double Man (1941) begins with an epigraph from Montaigne, ‘We are, I know not how, double in ourselves, so that what we believe we disbelieve, and cannot rid ourselves of what we condemn.’

*

But he wasn’t really double, any more than anyone is double: anyone, everyone is multiple.

So, to go back to that question, who the hell was W. H. Auden?

He was a poet, a dramatist, a librettist, a teacher, an amateur psychologist, a journalist, a reviewer, an anthologist, a critic, a Yorkshireman, an Englishman, an American.

That’ll do, for starters.

Not Standing

So why is he sitting at the start of the poem?

And how is he sitting?

Is he on a chair? A stool? A bench?

Is he perched on a stoop or a stairwell?

*

(And – my wife asks, appalled, having read the first draft of this book, twenty-five years after I embarked upon it – are you really going to spend all that time worrying over every single word in the poem?)

Many poets have some idiosyncrasy or tic of style which can madden the reader if he finds their work basically unsympathetic, but which, if he likes it, becomes endearing like the foibles of an old friend.

(Auden, ‘Walter de la Mare’)

Of course I’m not going to worry over every single word in the poem. That would be ludicrous – unfeasible, and unhealthy.

*

(Really unhealthy. Fatal. In a lecture on ‘The Art of Literature and Commonsense’, collected in his Lectures on Literature, Nabokov remarks that ‘In a sense, we are all crashing to our death from the top story of our birth […] and wondering with an immortal Alice in Wonderland at the patterns of the passing wall. This capacity to wonder at trifles – no matter the imminent peril – these asides of the spirit […] are the highest forms of consciousness.’ Twenty-five years of falling to my death, gazing around, wondering at trifles.)

*

Let me reassure you: we may have started out on the scenic route, but I promise there are going to be short-cuts. There’s just a lot of heavy lifting to get through at the start. Think of all this as backstory. Think of these early chapters as foundation stones, as building blocks, as … bricks.

(In Joe Brainard’s cult classic I Remember he writes, ‘I remember a back-drop of a brick wall I painted for a play. I painted each red brick in by hand. Afterwards it occurred to me that I could have just painted the whole thing red and put in the white lines.’ I’m not going to be painting each red brick by hand: after a while, I’ll be sketching in white lines.)

Civilization is a precarious balance between what Professor Whitehead has called barbaric vagueness and trivial order.

(Auden, ‘The Greeks and Us’)

(I have been reading – I have been teaching – Erich Auerbach’s essay ‘Odysseus’ Scar’, the first chapter of his book Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, published in 1946. It is surely one of the last great, readable works of literary criticism, in which Auerbach distinguishes between Hellenistic and Hebraic modes of storytelling:

It would be difficult, then, to imagine styles more contrasted than those of these two equally ancient and equally epic texts. On the one hand, externalized, uniformly illuminated phenomena, at a definite time and in a definite place, connected together without lacunae in a perpetual foreground; thoughts and feeling completely expressed; events taking place in leisurely fashion and with very little of suspense. On the other hand, the externalization of only so much of the phenomena as is necessary for the purpose of the narrative, all else left in obscurity; the decisive points of the narrative alone are emphasized, what lies between is nonexistent; time and place are undefined and call for interpretation; thoughts and feeling remain unexpressed, are only suggested by the silence and the fragmentary speeches; the whole, permeated with the most unrelieved suspense and directed toward a single goal (and to that extent far more of a unity), remains mysterious and ‘fraught with background.’

It’s like that old Lenny Bruce routine – Jewish or goyish? In Bruce’s estimation, Count Basie is Jewish, Ray Charles is Jewish – but Eddie Cantor, Eddie Cantor is goyish. The joke being that Eddie Cantor was Jewish, but he was nothing more than a smooth, crowd-pleasing entertainer. ‘If you live in New York or any other big city, you are Jewish. It doesn’t matter even if you’re Catholic; if you live in New York, you’re Jewish. If you live in Butte, Montana, you’re going to be goyish even if you’re Jewish.’ Auden was a High Church Anglican, but he’s definitely Jewish, in the same way Count Basie and Ray Charles are Jewish: his best poems are Hebraic rather than Hellenistic. They are fraught with background.)

*

I imagine Auden sitting in a straight-backed chair, both feet flat on the floor, upright, sitting slightly forward, intent – like a sphinx, benevolent, ferocious, strong.

*

One of the most famous of the early photographs of Auden is the head-and-shoulders snap taken by Eric Bramall in 1928, showing Auden sitting with head bowed, lighting a cigarette. Or at least, I think he’s sitting – I’m not entirely sure. It’s not quite clear. The image has been reproduced numerous times on book covers and in feature articles and probably owes its enduring appeal to its ambiguity: the pose is simultaneously feminine and macho, coy and defiant; Bramall has captured a gesture of the kind that Roland Barthes describes, in Camera Lucida (1980), as ‘apprehended at the point in its course where the normal eye cannot arrest it’, providing a privileged glimpse that stimulates in the viewer a secret or erotic thrill. W. H. Auden is Humphrey Bogart. He is Marlene Dietrich. Joan Didion. Tom Waits. (The critic Cyril Connolly admitted to having been ‘obsessed’ with Auden’s physical appearance, recalling a homoerotic dream in which Auden ‘indicated two small firm breasts’ and teased him with the words, ‘Well, Cyril, how do you like my lemons?’)

There’s no denying it. Look at the photos.

Auden is sexy.

Seriously.

*

Anyway. How he is sitting is less important than the fact that he is sitting: at the outset of the poem, he is assuming a definite relationship with and towards the world and towards the reader. He is adopting a particular posture.

What he’s not doing is standing.

*

After a decade of running around all over the place – travelling to Iceland and to China and to Spain, and also undertaking vast intellectual journeys, from Marx to Freud and on towards Kierkegaard – sitting was something that Auden now believed people should be doing: being rather than doing, thinking rather than acting. He began his Smith College Commencement Address in June 1940 with these words:

On this quiet June morning the war is the dreadful background of the thoughts of us all, and it is difficult indeed to think of anything except the agony and death going on a few thousand miles to the east and west of this hall. While those whom we love are dying or in terrible danger, the overwhelming desire to do something this minute to stop it makes it hard to sit still and think. Nevertheless that is our particular duty in this place at this hour.

It is our particular duty in this place at this hour to sit with him.

*

(In the poems where Auden is most truly himself, he is either sitting or lying down: ‘Out on the lawn I lie in bed’; ‘Lay your sleeping head, my love’; the flirtatious male of ‘In Praise of Limestone’ who ‘lounges / Against a rock in the sunlight, never doubting / That for all his faults he is loved.’)

*

And if he’s not standing, he’s certainly not walking.

*

(After all these years, I realise I have no idea how Auden might have walked. I know in his later life he was famous for shuffling around outside in his carpet slippers, but how exactly did he walk? What was his gait? The truth is, I know both too much about Auden – endless, useless facts about him – and absolutely nothing. I know a lot of useless facts about a lot of writers: about William Burroughs, I know how he injected his morphine and how he scored his Benzedrine inhalers; I know the precise details of his sexual relationship with Allen Ginsberg, including the size of his penis; I know all about Marianne Moore’s tricorne hats, and Elizabeth Bishop’s taste in home furnishings; I know about Jack London’s sweet tooth; I have read Reiner Stach on Kafka; and Richard Ellmann and Michael Holroyd on everyone. All of these books, all of this endless information about writers – and for what? If Auden were in the distance now, walking away from me, I wouldn’t be able to recognise him. After all these years, I couldn’t spot him in a crowd. He remains a total stranger.)

In grasping the character of a society, as in judging the character of an individual, no documents, statistics, ‘objective’ measurements can ever compete with the single intuitive glance.

(Auden, ‘The American Scene’)

In his essay ‘My First Acquaintance with Poets’ (1823), William Hazlitt recalls one fine morning, in the middle of winter in 1798, going for a walk with Coleridge:

I observed that he continually crossed me on the way by shifting from one side of the foot-path to the other. This struck me as an odd movement; but I did not at the time connect it with any instability of purpose or involuntary change of principle, as I have done since. He seemed unable to keep on in a straight line.

Coleridge’s strange saunter was matched only by his curious conversation. ‘In digressing,’ writes Hazlitt, ‘in dilating, in passing from subject to subject, he appeared to me to float in air, to slide on ice.’

I can’t imagine Auden sliding, or indeed shimmering, like Jeeves. Striding, maybe? No. Slouching? A little. Sauntering? Strolling? Strutting? Slinking? Shambling? No. No. No. Schlepping? Maybe, a little.

Auden, I imagine, would have schlepped like a mensch.

*

(He loved this sort of thing himself, of course, categorising people according to some weird feature. In The Orators, for example:

Three kinds of enemy walk – the grandiose stunt – the melancholic stagger – the paranoic sidle.

Three kinds of enemy bearing – the condor stoop – the toad stupor – the robin’s stance.

Three kinds of highly entertaining bullshit.)

*

Just because he’s sitting, he’s not necessarily immobile. He’s not inactive. He is observing. He is concentrating. He is preparing himself for the poem, perhaps, gathering his energies. When we think of authors sitting, we imagine them sitting with single-mindedness and with purpose – don’t we? – sitting still but getting somewhere, going inwards.

*

Or maybe he’s just posing. He’s pouting. He’s sitting for a portrait.

(There is no recent book-length study of the phenomenon of the poet as pin-up, as far as I know. The best I can find is David Piper’s The Image of the Poet, which was published in 1982, long before our current crop of selfie-loving Insta poets. Auden would have made an excellent Insta poet: he loved the camera. He was arguably – at least, I shall argue here, now – the first poet of the technologised twentieth century, his career formed not just through books but through the media of film, photography, radio, television, mass-circulation newspapers and poetry readings. Not only was he enormously ambitious, he was endlessly inventive. He used all the tools available to him. He took a camera to Iceland in 1936, and the photographs were included in his and MacNeice’s travelogue, Letters from Iceland. At his parties in the 1950s, long before Warhol’s snapping and spooling at the Factory, he would go around photographing his guests. The critic Edmund Wilson describes a truly Warholian scene at Auden’s birthday party in 1955: ‘Hordes of people arrived; the room became crowded and smoke-filled and the conversation deafening. Wystan went around with a camera taking flashlights of his guests. When he came to the group in which I was, I hung a handkerchief over my face at the moment he was taking the picture.’)