The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

(3.) When a man is indignant or defiant does he frown, hold his body and head erect, square his shoulders and clench his fists?

(4) When considering deeply on any subject, or trying to understand any puzzle, does he frown, or wrinkle the skin beneath the lower eyelids?

(5.) When in low spirits, are the corners of the mouth depressed, and the inner corner of the eyebrows raised by that muscle which the French call the "Grief muscle"? The eyebrow in this state becomes slightly oblique, with a little swelling at the Inner end; and the forehead is transversely wrinkled in the middle part, but not across the whole breadth, as when the eyebrows are raised in surprise. (6.) When in good spirits do the eyes sparkle, with the skin a little wrinkled round and under them, and with the mouth a little drawn back at the corners?

(7.) When a man sneers or snarls at another, is the corner of the upper lip over the canine or eye tooth raised on the side facing the man whom he addresses?

(8) Can a dogged or obstinate expression be recognized, which is chiefly shown by the mouth being firmly closed, a lowering brow and a slight frown?

(9.) Is contempt expressed by a slight protrusion of the lips and by turning up the nose, and with a slight expiration?

(10) Is disgust shown by the lower lip being turned down, the upper lip slightly raised, with a sudden expiration, something like incipient vomiting, or like something spit out of the mouth?

(11.) Is extreme fear expressed in the same general manner as with Europeans?

(12.) Is laughter ever carried to such an extreme as to bring tears into the eyes?

(13.) When a man wishes to show that he cannot prevent something being done, or cannot himself do something, does he shrug his shoulders, turn inwards his elbows, extend outwards his hands and open the palms; with the eyebrows raised?

(14) Do the children when sulky, pout or greatly protrude the lips?

(15.) Can guilty, or sly, or jealous expressions be recognized? though I know not how these can be defined.

(16.) Is the head nodded vertically in affirmation, and shaken laterally in negation?

Observations on natives who have had little communication with Europeans would be of course the most valuable, though those made on any natives would be of much interest to me. General remarks on expression are of comparatively little value; and memory is so deceptive that I earnestly beg it may not be trusted. A definite description of the countenance under any emotion or frame of mind, with a statement of the circumstances under which it occurred, would possess much value.

To these queries I have received thirty-six answers from different observers, several of them missionaries or protectors of the aborigines, to all of whom I am deeply indebted for the great trouble which they have taken, and for the valuable aid thus received. I will specify their names, &c., towards the close of this chapter, so as not to interrupt my present remarks. The answers relate to several of the most distinct and savage races of man. In many instances, the circumstances have been recorded under which each expression was observed, and the expression itself described. In such cases, much confidence may be placed in the answers. When the answers have been simply yes or no, I have always received them with caution. It follows, from the information thus acquired, that the same state of mind is expressed throughout the world with remarkable uniformity; and this fact is in itself interesting as evidence of the close similarity in bodily structure and mental disposition of all the races, of mankind.

Sixthly, and lastly, I have attended as closely as I could, to the expression of the several passions in some of the commoner animals; and this I believe to be of paramount importance, not of course for deciding how far in man certain expressions are characteristic of certain states of mind, but as affording the safest basis for generalisation on the causes, or origin, of the various movements of Expression. In observing animals, we are not so likely to be biassed by our imagination; and we may feel safe that their expressions are not conventional.

From the reasons above assigned, namely, the fleeting nature of some expressions (the changes in the features being often extremely slight); our sympathy being easily aroused when we behold any strong emotion, and our attention thus distracted; our imagination deceiving us, from knowing in a vague manner what to expect, though certainly few of us know what the exact changes in the countenance are; and lastly, even our long familiarity with the subject, – from all these causes combined, the observation of Expression is by no means easy, as many persons, whom I have asked to observe certain points, have soon discovered. Hence it is difficult to determine, with certainty, what are the movements of the features and of the body, which commonly characterize certain states of the mind. Nevertheless, some of the doubts and difficulties have, as I hope, been cleared away by the observation of infants, – of the insane, – of the different races of man, – of works of art, – and lastly, of the facial muscles under the action of galvanism, as effected by Dr. Duchenne.

But there remains the much greater difficulty of understanding the cause or origin of the several expressions, and of judging whether any theoretical explanation is trustworthy. Besides, judging as well as we can by our reason, without the aid of any rules, which of two or more explanations is the most satisfactory, or are quite unsatisfactory, I see only one way of testing our conclusions. This is to observe whether the same principle by which one expression can, as it appears, be explained, is applicable in other allied cases; and especially, whether the same general principles can be applied with satisfactory results, both to man and the lower animals. This latter method, I am inclined to think, is the most serviceable of all. The difficulty of judging of the truth of any theoretical explanation, and of testing it by some distinct line of investigation, is the great drawback to that interest which the study seems well fitted to excite.

Finally, with respect to my own observations, I may state that they were commenced in the year 1838; and from that time to the present day, I have occasionally attended to the subject. At the above date, I was already inclined to believe in the principle of evolution, or of the derivation of species from other and lower forms. Consequently, when I read Sir C. Bell's great work, his view, that man had been created with certain muscles specially adapted for the expression of his feelings, struck me as unsatisfactory. It seemed probable that the habit of expressing our feelings by certain movements, though now rendered innate, had been in some manner gradually acquired. But to discover how such habits had been acquired was perplexing in no small degree. The whole subject had to be viewed under a new aspect, and each expression demanded a rational explanation. This belief led me to attempt the present work, however imperfectly it may have been executed. —

I will now give the names of the gentlemen to whom, as I have said, I am deeply indebted for information in regard to the expressions exhibited by various races of man, and I will specify some of the circumstances under which the observations were in each case made. Owing to the great kindness and powerful influence of Mr. Wilson, of Hayes Place, Kent, I have received from Australia no less than thirteen sets of answers to my queries. This has been particularly fortunate, as the Australian aborigines rank amongst the most distinct of all the races of man. It will be seen that the observations have been chiefly made in the south, in the outlying parts of the colony of Victoria; but some excellent answers have been received from the north.

Mr. Dyson Lacy has given me in detail some valuable observations, made several hundred miles in the interior of Queensland. To Mr. R. Brough Smyth, of Melbourne, I am much indebted for observations made by himself, and for sending me several of the following letters, namely: – From the Rev. Mr. Hagenauer, of Lake Wellington, a missionary in Gippsland, Victoria, who has had much experience with the natives. From Mr. Samuel Wilson, a landowner, residing at Langerenong, Wimmera, Victoria. From the Rev. George Taplin, superintendent of the native Industrial Settlement at Port Macleay. From Mr. Archibald G. Lang, of Coranderik, Victoria, a teacher at a school where aborigines, old and young, are collected from all parts of the colony. From Mr. H. B. Lane, of Belfast, Victoria, a police magistrate and warden, whose observations, as I am assured, are highly trustworthy. From Mr. Templeton Bunnett, of Echuca, whose station is on the borders of the colony of Victoria, and who has thus been able to observe many aborigines who have had little intercourse with white men. He compared his observations with those made by two other gentlemen long resident in the neighbourhood. Also from Mr. J. Bulmer, a missionary in a remote part of Gippsland, Victoria.

I am also indebted to the distinguished botanist, Dr. Ferdinand Muller, of Victoria, for some observations made by himself, and for sending me others made by Mrs. Green, as well as for some of the foregoing letters.

In regard to the Maoris of New Zealand, the Rev. J. W. Stack has answered only a few of my queries; but the answers have been remarkably full, clear, and distinct, with the circumstances recorded under which the observations were made.

The Rajah Brooke has given me some information with respect to the Dyaks of Borneo.

Respecting the Malays, I have been highly successful; for Mr. F. Geach (to whom I was introduced by Mr. Wallace), during his residence as a mining engineer in the interior of Malacca, observed many natives, who had never before associated with white men. He wrote me two long letters with admirable and detailed observations on their expression. He likewise observed the Chinese immigrants in the Malay archipelago.

The well-known naturalist, H. M. Consul, Mr. Swinhoe, also observed for me the Chinese in their native country; and he made inquiries from others whom he could trust.

In India Mr. H. Erskine, whilst residing in his official capacity in the Admednugur District in the Bombay Presidency, attended to the expression of the inhabitants, but found much difficulty in arriving at any safe conclusions, owing to their habitual concealment of all emotions in the presence of Europeans. He also obtained information for me from Mr. West, the Judge in Canara, and he consulted some intelligent native gentlemen on certain points. In Calcutta Mr. J. Scott, curator of the Botanic Gardens, carefully observed the various tribes of men therein employed during a considerable period, and no one has sent me such full and valuable details. The habit of accurate observation, gained by his botanical studies, has been brought to bear on our present subject. For Ceylon I am much indebted to the Rev. S. O. Glenie for answers to some of my queries.

Turning to Africa, I have been unfortunate with respect to the negroes, though Mr. Winwood Reade aided me as far as lay in his power. It would have been comparatively easy to have obtained information in regard to the negro slaves in America; but as they have long associated with white men, such observations would have possessed little value. In the southern parts of the continent Mrs. Barber observed the Kafirs and Fingoes, and sent me many distinct answers. Mr. J. P. Mansel Weale also made some observations on the natives, and procured for me a curious document, namely, the opinion, written in English, of Christian Gaika, brother of the Chief Sandilli, on the expressions of his fellow-countrymen. In the northern regions of Africa Captain Speedy, who long resided with the Abyssinians, answered my queries partly from memory and partly from observations made on the son of King Theodore, who was then under his charge. Professor and Mrs. Asa Gray attended to some points in the expressions of the natives, as observed by them whilst ascending the Nile.

On the great American continent Mr. Bridges, a catechist residing with the Fuegians, answered some few questions about their expression, addressed to him many years ago. In the northern half of the continent Dr. Rothrock attended to the expressions of the wild Atnah and Espyox tribes on the Nasse River, in North-Western America. Mr. Washington Matthews Assistant-Surgeon in the United States Army, also observed with special care (after having seen my queries, as printed in the 'Smithsonian Report') some of the wildest tribes in the Western parts of the United States, namely, the Tetons, Grosventres, Mandans, and Assinaboines; and his answers have proved of the highest value.

Lastly, besides these special sources of information, I have collected some few facts incidentally given in books of travels. —

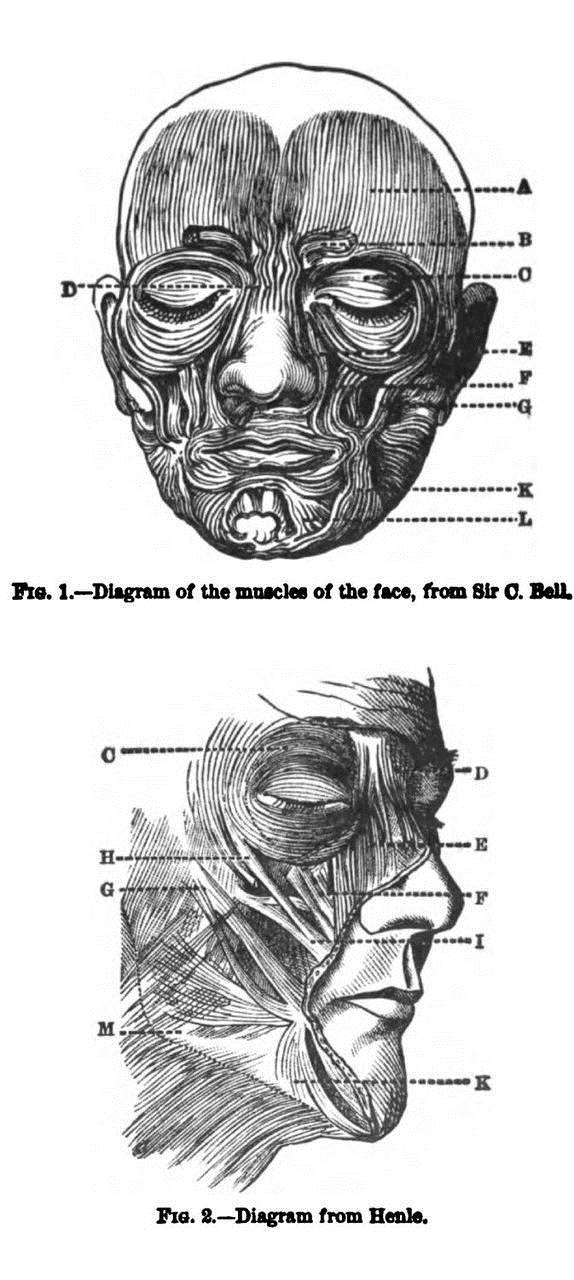

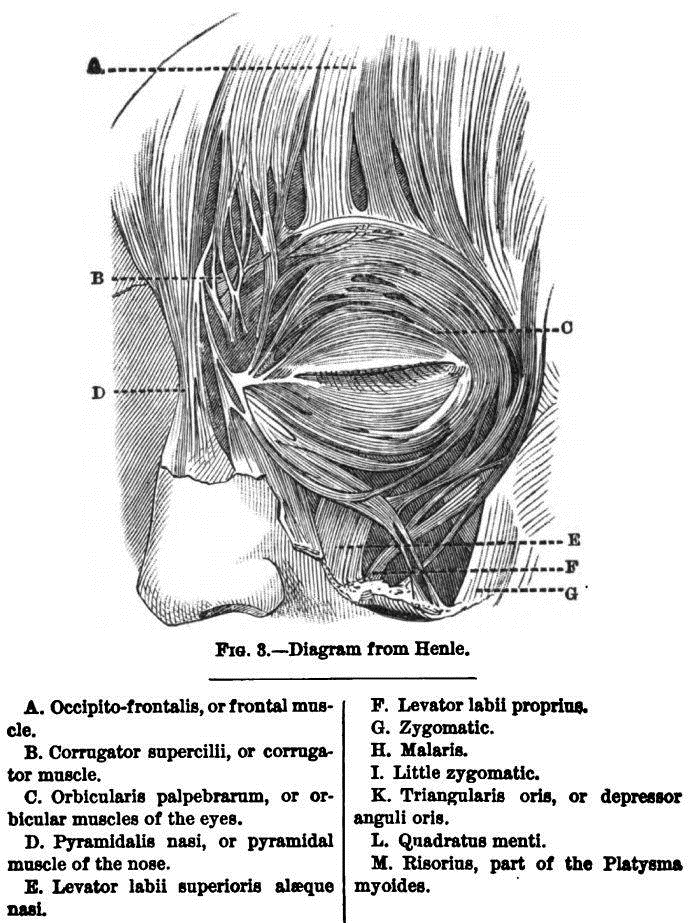

As I shall often have to refer, more especially in the latter part of this volume, to the muscles of the human face, I have had a diagram (fig. 1) copied and reduced from Sir C. Bell's work, and two others, with more accurate details (figs. 2 and 3), from Herde's well-known 'Handbuch der Systematischen Anatomie des Menschen.' The same letters refer to the same muscles in all three figures, but the names are given of only the more important ones to which I shall have to allude. The facial muscles blend much together, and, as I am informed, hardly appear on a dissected face so distinct as they are here represented. Some writers consider that these muscles consist of nineteen pairs, with one unpaired;[20] but others make the number much larger, amounting even to fifty-five, according to Moreau. They are, as is admitted by everyone who has written on the subject, very variable in structure; and Moreau remarks that they are hardly alike in half-a-dozen subjects.[21] They are also variable in function. Thus the power of uncovering the canine tooth on one side differs much in different persons. The power of raising the wings of the nostrils is also, according to Dr. Piderit,[22] variable in a remarkable degree; and other such cases could be given.

Finally, I must have the pleasure of expressing my obligations to Mr. Rejlander for the trouble which he has taken in photographing for me various expressions and gestures. I am also indebted to Herr Kindermann, of Hamburg, for the loan of some excellent negatives of crying infants; and to Dr. Wallich for a charming one of a smiling girl. I have already expressed my obligations to Dr. Duchenne for generously permitting me to have some of his large photographs copied and reduced. All these photographs have been printed by the Heliotype process, and the accuracy of the copy is thus guaranteed. These plates are referred to by Roman numerals.

I am also greatly indebted to Mr. T. W. Wood for the extreme pains which he has taken in drawing from life the expressions of various animals. A distinguished artist, Mr. Riviere, has had the kindness to give me two drawings of dogs – one in a hostile and the other in a humble and caressing frame of mind. Mr. A. May has also given me two similar sketches of dogs. Mr. Cooper has taken much care in cutting the blocks. Some of the photographs and drawings, namely, those by Mr. May, and those by Mr. Wolf of the Cynopithecus, were first reproduced by Mr. Cooper on wood by means of photography, and then engraved: by this means almost complete fidelity is ensured.

CHAPTER I. – GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF EXPRESSION

The three chief principles stated – The first principle – Serviceable actions become habitual in association with certain states of the mind, and are performed whether or not of service in each particular case – The force of habit – Inheritance – Associated habitual movements in man – Reflex actions – Passage of habits into reflex actions – Associated habitual movements in the lower animals – Concluding remarks.

I WILL begin by giving the three Principles, which appear to me to account for most of the expressions and gestures involuntarily used by man and the lower animals, under the influence of various emotions and sensations.[101] I arrived, however, at these three Principles only at the close of my observations. They will be discussed in the present and two following chapters in a general manner. Facts observed both with man and the lower animals will here be made use of; but the latter facts are preferable, as less likely to deceive us. In the fourth and fifth chapters, I will describe the special expressions of some of the lower animals; and in the succeeding chapters those of man. Everyone will thus be able to judge for himself, how far my three principles throw light on the theory of the subject. It appears to me that so many expressions are thus explained in a fairly satisfactory manner, that probably all will hereafter be found to come under the same or closely analogous heads. I need hardly premise that movements or changes in any part of the body, – as the wagging of a dog's tail, the drawing back of a horse's ears, the shrugging of a man's shoulders, or the dilatation of the capillary vessels of the skin, – may all equally well serve for expression. The three Principles are as follows.

I. The principle of serviceable associated Habits. – Certain complex actions are of direct or indirect service under certain states of the mind, in order to relieve or gratify certain sensations, desires, &c.; and whenever the same state of mind is induced, however feebly, there is a tendency through the force of habit and association for the same movements to be performed, though they may not then be of the least use. Some actions ordinarily associated through habit with certain states of the mind may be partially repressed through the will, and in such cases the muscles which are least under the separate control of the will are the most liable still to act, causing movements which we recognize as expressive. In certain other cases the checking of one habitual movement requires other slight movements; and these are likewise expressive.

II. The principle of Antithesis. – Certain states of the mind lead to certain habitual actions, which are of service, as under our first principle. Now when a directly opposite state of mind is induced, there is a strong and involuntary tendency to the performance of movements of a directly opposite nature, though these are of no use; and such movements are in some cases highly expressive.

III. The principle of actions due to the constitution of the Nervous System, independently from the first of the Will, and independently to a certain extent of Habit. – When the sensorium is strongly excited, nerve-force is generated in excess, and is transmitted in certain definite directions, depending on the connection of the nerve-cells, and partly on habit: or the supply of nerve-force may, as it appears, be interrupted. Effects are thus produced which we recognize as expressive. This third principle may, for the sake of brevity, be called that of the direct action of the nervous system.

With respect to our first Principle, it is notorious how powerful is the force of habit. The most complex and difficult movements can in time be performed without the least effort or consciousness. It is not positively known how it comes that habit is so efficient in facilitating complex movements; but physiologists admit[102] "that the conducting power of the nervous fibres increases with the frequency of their excitement." This applies to the nerves of motion and sensation, as well as to those connected with the act of thinking. That some physical change is produced in the nerve-cells or nerves which are habitually used can hardly be doubted, for otherwise it is impossible to understand how the tendency to certain acquired movements is inherited. That they are inherited we see with horses in certain transmitted paces, such as cantering and ambling, which are not natural to them, – in the pointing of young pointers and the setting of young setters – in the peculiar manner of flight of certain breeds of the pigeon, &c. We have analogous cases with mankind in the inheritance of tricks or unusual gestures, to which we shall presently recur. To those who admit the gradual evolution of species, a most striking instance of the perfection with which the most difficult consensual movements can be transmitted, is afforded by the humming-bird Sphinx-moth (Macroglossa); for this moth, shortly after its emergence from the cocoon, as shown by the bloom on its unruffled scales, may be seen poised stationary in the air, with its long hair-like proboscis uncurled and inserted into the minute orifices of flowers; and no one, I believe, has ever seen this moth learning to perform its difficult task, which requires such unerring aim.

When there exists an inherited or instinctive tendency to the performance of an action, or an inherited taste for certain kinds of food, some degree of habit in the individual is often or generally requisite. We find this in the paces of the horse, and to a certain extent in the pointing of dogs; although some young dogs point excellently the first time they are taken out, yet they often associate the proper inherited attitude with a wrong odour, and even with eyesight. I have heard it asserted that if a calf be allowed to suck its mother only once, it is much more difficult afterwards to rear it by hand.[103] Caterpillars which have been fed on the leaves of one kind of tree, have been known to perish from hunger rather than to eat the leaves of another tree, although this afforded them their proper food, under a state of nature;[104] and so it is in many other cases.

The power of Association is admitted by everyone. Mr. Bain remarks, that "actions, sensations and states of feeling, occurring together or in close succession, tend to grow together, or cohere, in such a way that when any one of them is afterwards presented to the mind, the others are apt to be brought up in idea."[105] It is so important for our purpose fully to recognize that actions readily become associated with other actions and with various states of the mind, that I will give a good many instances, in the first place relating to man, and afterwards to the lower animals. Some of the instances are of a very trifling nature, but they are as good for our purpose as more important habits. It is known to everyone how difficult, or even impossible it is, without repeated trials, to move the limbs in certain opposed directions which have never been practised. Analogous cases occur with sensations, as in the common experiment of rolling a marble beneath the tips of two crossed fingers, when it feels exactly like two marbles. Everyone protects himself when falling to the ground by extending his arms, and as Professor Alison has remarked, few can resist acting thus, when voluntarily falling on a soft bed. A man when going out of doors puts on his gloves quite unconsciously; and this may seem an extremely simple operation, but he who has taught a child to put on gloves, knows that this is by no means the case.

When our minds are much affected, so are the movements of our bodies; but here another principle besides habit, namely the undirected overflow of nerve-force, partially comes into play. Norfolk, in speaking of Cardinal Wolsey, says —

"Some strange commotion Is in his brain; he bites his lip and starts; Stops on a sudden, looks upon the ground, Then, lays his finger on his temple: straight, Springs out into fast gait; then, stops again, Strikes his breast hard; and anon, he casts His eye against the moon: in most strange postures We have seen him set himself." —Hen. VIII., act 3, sc. 2.A vulgar man often scratches his head when perplexed in mind; and I believe that he acts thus from habit, as if he experienced a slightly uncomfortable bodily sensation, namely, the itching of his head, to which he is particularly liable, and which he thus relieves. Another man rubs his eyes when perplexed, or gives a little cough when embarrassed, acting in either case as if he felt a slightly uncomfortable sensation in his eyes or windpipe.[106]

From the continued use of the eyes, these organs are especially liable to be acted on through association under various states of the mind, although there is manifestly nothing to be seen. A man, as Gratiolet remarks, who vehemently rejects a proposition, will almost certainly shut his eyes or turn away his face; but if he accepts the proposition, he will nod his head in affirmation and open his eyes widely. The man acts in this latter case as if he clearly saw the thing, and in the former case as if he did not or would not see it. I have noticed that persons in describing a horrid sight often shut their eyes momentarily and firmly, or shake their heads, as if not to see or to drive away something disagreeable; and I have caught myself, when thinking in the dark of a horrid spectacle, closing my eyes firmly. In looking suddenly at any object, or in looking all around, everyone raises his eyebrows, so that the eyes may be quickly and widely opened; and Duchenne remarks that[107] a person in trying to remember something often raises his eyebrows, as if to see it. A Hindoo gentleman made exactly the same remark to Mr. Erskine in regard to his countrymen. I noticed a young lady earnestly trying to recollect a painter's name, and she first looked to one corner of the ceiling and then to the opposite corner, arching the one eyebrow on that side; although, of course, there was nothing to be seen there.