The Secret of the Totem

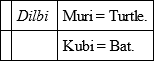

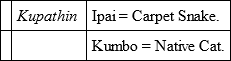

Suppose for the sake of argument that the class names denote, or once denoted animals, so that, say —

In phratry

It is obvious that male Turtle would marry female Cat, and (with maternal descent) their children would, by class name, be Carpet Snakes. Bat would marry Carpet Snake, and their children would, by class name, be Cats. Persons of each generation would thus belong to classes of different animal names for ever, and no one might marry into either his or her own phratry, his or her own totem, or his or her own generation, that is, into his or her own class. It is exactly (where the classes bear animal names) as if two generations had totems. The mothers of Muri class in Dilbi would have Turtle, the mothers in Kupathin (Ipai) would have Carpet Snake. Their children, in Kupathin, would have Cat. Not only the phratries and the totem kins, but each successive generation, would thus be delimited by bearing an animal name, and marriage would be forbidden between all persons not of different animal-named phratries, different animal-named totem kins, and different animal-named generations. In many cases, we repeat, the names of the phratries and of the classes have not yet been translated, and the meanings are unknown to the natives themselves. That the class names were originally animal names is a mere hypothesis, based on few examples.

Say I am of phratry Crow, of totem Lizard, of generation and matrimonial class Turtle; then I must marry only a woman of phratry Eagle Hawk, of any totem in Eagle Hawk phratry,15 and of generation and class name Cat. Our children, with female descent, will be of phratry Eagle Hawk, of totem the mother's, and of generation and class name Carpet Snake. Their children will be of phratry Crow, of totem the mother's, and of generation and class name Cat again; and so on for ever. Each generation in a phratry has its class name, and may not marry within that name. The next generation has the other class name, and may not marry within that. Assuming that phratry names, totem names, and generation names are always names of animals (or of other objects in nature), the laws would amount, we repeat, simply to this: No person may marry another person who, by phratry, or totem, or generation, owns the same hereditary animal name or other name as himself or herself. Moreover no one may marry a person (where matrimonial classes exist) who bears the same class or generation name as his mother or father.

In practice the rules are thus quite simple, mistake is impossible – complicated as the arrangements look on paper. Where totem and phratry names only exist, a man has merely to ask a woman, "What is your phratry name?" If it is his own, an amour is forbidden. Where phratry names are obsolete, and classes exist, he has only to ask, "What is your class name?" If it is that of either class in his own phratry of the tribe, to love is to break a sacred law. It is not necessary, as a rule, even to ask the totem name. What looks so perplexing is in essence, and in practical working, of extreme simplicity. But some tribes have deliberately modified the rules, to facilitate marriage.

The conspicuous practical result of the Class arrangement (not primitive), is that just as totem law makes it impossible for a person to marry a sister or brother uterine, so Class law makes a marriage between father and daughter, mother and son, impossible.16 But such marriages never occur in Australian tribes of pristine organisation (1) which have no class names, no collective names for successive generations. The origin of these class or generation names is a problem which will be discussed later.

Such is the Class system where it exists in tribes with female descent. It has often led to the loss and disappearance of the phratry names, which are forgotten, since the two sets of opposed class names do the phratry work.

We have next (3) the same arrangements with descent reckoned in the male line. This prevails on the south-east coast, from Hervey River to Warwick. In Gippsland, and in a section round Melbourne, there were "anomalous" arrangements which need not now detain us; the archaic systems tended to die out altogether.

All these south central (Dieri), southern, and eastern tribes may be studied in Mr. Howitt's book, already cited, which contains the result of forty years' work, the information being collected partly by personal research and partly through many correspondents. Mr. Howitt has viewed the initiatory ceremonies of more than one tribe, and is familiar with their inmost secrets.

For the tribes of the centre and north we must consult two books, the fruits of the personal researches of Mr. Baldwin Spencer, M.A., F.R.S., Professor of Biology in the University of Melbourne, and of Mr. F. J. Gillen, Sub-Protector of Aborigines, South Australia.17 For many years Mr. Gillen has been in the confidence of the tribes, and he and Mr. Spencer have passed many months in the wilds, being admitted to view the most secret ceremonies, and being initiated into the myths of the people. Their photographs of natives are numerous and excellent.

These observers begin in the south centre, where Mr. Howitt leaves off in his northerly researches, and go north. They start with the Urabunna tribe, north-east of Lake Eyre, congeners of Mr. Howitt's Dieri, and speaking a dialect akin to theirs, while the tribe intermarry marry with the Arunta (whose own dialect has points in common with theirs) of the centre of the continent These Urabunna are apparently in the form of social organisation which we style primitive (No. 1), but there are said, rather vaguely, to be more restrictions on marriage than is usual, people of one totem in Kiraru phratry being restricted to people of one totem in Matteri phratry.18

They have phratries, totem kins, apparently no matrimonial classes (some of their rules are imperfectly ascertained), and they reckon descent in the female line. But, like the Dieri (and unlike the tribes of the south and east), they practise subincision; they have, or are said to have, no belief in "a supernatural anthropomorphic great Being"; they believe in "old semi-human ancestors," who scattered about spirits, which are perpetually reincarnated in new members of the tribe; they practise totemic magic; and they cultivate the Dieri custom of allotting paramours. Thus, by social organisation, they attach themselves to the south-eastern tribes (1), but, like the Dieri, and even more so (for, unlike the Dieri, they believe in reincarnation), they agree in ceremonies, and in the general idea of their totemic magic, rites, and mythical ideas, with tribes who, as regards social organisation, are in state (4), reckon descent in the male line, and possess, not four, but eight matrimonial classes.

This institution of eight classes is developing in the Arunta "nation," the people of the precise centre of Australia, who march with, and intermarry with, the Urabunna; at least the names for the second set of four matrimonial classes, making eight in all, are reaching the Arunta from the northern tribes. All the way further north to the Gulf of Carpentaria, male descent and eight classes prevail, with subincision, prolonged and complex ceremonials, the belief in reincarnation of primal semi-human, semi-bestial ancestors, and the absence (except in the Kaitish tribe, next the Arunta) of any known belief in what Mr. Howitt calls the "All Father." Totemic magic also is prevalent, dwindling as you approach the north-east coast. In consequence of reckoning in the male line (which necessarily causes most of the dwellers in a group to be of the same totem), local organisation is more advanced in these tribes than in the south and east.

We next speak of social organisation (5), namely, that of the Arunta and Kaitish tribes, which is without example in any other known totemic society all over the world. The Arunta and Kaitish not only believe, like most northern and western tribes, in the perpetual reincarnation of ancestral spirits, but they, and they alone, hold that each such spirit, during discarnate intervals, resides in, or is mainly attached to, a decorated kind of stone amulet, called churinga nanja. These objects, with this myth, are not recorded as existing among other "nations." When a child is born, its friends hunt for its ancestral stone amulet in the place where its mother thinks that she conceived it, and around the nearest rendezvous of discarnate local totemic souls, all of one totem only. The amulet and the local totemic centre, with its haunted nanja rock or tree, determine the totem of the child. Thus, unlike all other totemists, the Arunta do not inherit their totems either from father or mother, or both. Totems are determined by local accident. Not being hereditary, they are not exogamous: here, and here alone, they do not regulate marriage. Men may, and do, marry women of their own totem, and their child's totem may neither be that of its father nor of its mother. The members of totem groups are really members of societies, which co-operatively work magic for the good of the totems. The question arises, Is this the primitive form of totemism? We shall later discuss that question (Chapter IV.).

Meanwhile we conceive the various types of social organisation to begin with the south-eastern phratries, totems, and female reckoning of descent (1) to advance to these plus male descent (2a), and to these with female descent and four matrimonial classes (2b). Next we place (3) that four-class system with male descent; next (4) the north-western system of male descent with eight matrimonial classes, and last (as anomalous in some respects), (5) the Arunta-Kaitish system of male descent, eight classes, and non-hereditary non-exogamous totems.

As regards ceremonial and belief, we place (1) the tribes south and east of the Dieri. (2) The Dieri. (3) The Urabunna, and north, central, and western tribes. (4) The Arunta. The Dieri and Urabunna we regard (at least the Dieri) as pristine in social organisation, with peculiarities all their own, but in ceremonial and belief more closely attached to the central, north, and west than to the south-eastern tribes. As concerns the bloody rites, Mr. Howitt inclines to the belief (corroborated by legends, whatever their value) that "a northern origin must ultimately be assigned to these ceremonies."19 It is natural to assume that the more cruel initiatory rites are the more archaic, and that the tribes which practise them are the more pristine. But this is not our opinion nor that of Messrs. Spencer and Gillen. The older rite is the mere knocking out of front teeth (also used by the Masai of East Central Africa). This rite, in Central Australia, "has lost its old meaning, its place has been taken by other rites."20 … Increased cruelty accompanies social advance in this instance. In another matter innovation comes from the north. Messrs. Spencer and Gillen are of the opinion that "changes in totemic matters have been slowly passing down from north to south." The eight classes, in place of four classes, are known as a matter of fact to have actually "reached the Arunta from the north, and at the present moment are spreading south-wards."21

Again, a feebler form of the reincarnation belief, namely, that souls of the young who die uninitiated are reincarnated, occurs in the Euahlayi tribe of north-western New South Wales.22 Whether the Euahlayi belief came from the north, in a limited way, or whether it is the germinal state of the northern belief, is uncertain. It is plain that if bloody rites and eight classes may come down from the north, totemic magic and the faith in reincarnation may also have done so, and thus modified the rites and "religious" opinions of the Dieri and Urabunna, who are said still to be, socially, in the most pristine state, that of phratries and female descent, without matrimonial classes.23 It is also obvious that if the Kaitish faith in a sky-dweller (rare in northern tribes) be a "sport," and if the Arunta churinga nanja, plus non-hereditary and non-exogamous totems, be a "sport," the Dieri and Urabunna custom, too, of solemnly allotted permanent paramours may be a thing of isolated and special development, not a survival of an age of "group marriage."

CHAPTER II

METHOD OF INQUIRY

Method of inquiry – Errors to be avoided – Origin of totemism not to be looked for among the "sports" of socially advanced tribes – Nor among tribes of male reckoning of descent – Nor in the myths explanatory of origin of totemism – Myths of origin of heraldic bearings compared – Tribes in state of ancestor-worship: their totemic myths cannot be true – Case of Bantu myths (African) – Their myth implies ancestor-worship – Another African myth derives tribal totems from tribal nicknames – No totemic myths are of any historic value – The use of conjecture – Every theory must start from conjecture – Two possible conjectures as to earliest men gregarious (the horde), or lonely sire, female mates, and off-spring – Five possible conjectures as to the animal names of kinships in relation to early society and exogamy – Theory of the author; of Professor Spencer; of Dr. Durkheim; of Mr. Hill-Tout; of Mr. Howitt – Note on McLennan's theory of exogamy.

We have now given the essential facts in the problem of early society as it exists in various forms among the most isolated and pristine peoples extant. It has been shown that the sets of seniority (classes), the exogamous moieties (phratries), and the kinships in each tribe bear names which, when translated, are usually found to denote animals. Especially the names of the totem kindreds, and of the totems, are commonly names of animals or plants. If we can discover why this is so, we are near the discovery of the origin of totemism. Meanwhile we offer some remarks as to the method to be pursued in the search for a theory which will colligate all the facts in the case, and explain the origin of totemic society. In the first place certain needful warnings must be given, certain reefs which usually wreck efforts to construct a satisfactory hypothesis must be marked.

First, it will be vain to look for the origin of totemism either among advanced and therefore non-pristine Australian types of tribal organisation, or among peoples not Australian, who are infinitely more forward than the Australians in the arts of life, and in the possession of property. Such progressive peoples may present many interesting social phenomena, but, as regards pure primitive totemism, they dwell on "fragments of a broken world." The totemic fragments, among them, are twisted and shattered strata, with fantastic features which cannot be primordial, but are metamorphic. Accounts of these societies are often puzzling, and the strange confused terms used by the reporters, especially in America, frequently make them unintelligible.

The learned, who are curious in these matters, would have saved themselves much time and labour had they kept two conspicuous facts before their eyes.

(1) It is useless to look for the origins of totemism among the peculiarities and "sports" which always attend the decadence of totemism, consequent on the change from female to male lineage, as Mr. Howitt, our leader in these researches, has always insisted. To search for the beginnings among late and abnormal phenomena, things isolated, done in a corner, and not found among the tribal organisations of the earliest types, is to follow a trail sure to be misleading.

(2) The second warning is to be inferred from the first. It is waste of time to seek for the origin of totemism in anything – an animal name, a sacred animal, a paternal soul tenanting an animal – which is inherited from its first owner, he being an individual ancestor male. Such inheritance implies the existence of reckoning descent in the male line, and totemism conspicuously began in, and is least contaminated in, tribes who reckon descent in the female line.

Another stone of stumbling comes from the same logical formation. The error is, to look for origins in myths about origins, told among advanced or early societies. If a people has advanced far in material culture, if it is agricultural, breeds cattle, and works the metals, of course it cannot be primitive. However, it may retain vestiges of totemism, and, if it does, it will explain them by a story, a myth of its own, just as modern families, and even cities, have their myths to account for the origin, now forgotten, of their armorial bearings, or crests – the dagger in the city shield, the skene of the Skenes, the sawn tree of the Hamiltons, the lyon of the Stuarts.

Now an agricultural, metallurgic people, with male descent, in the middle barbarism, will explain its survivals of totemism by a myth natural in its intellectual and social condition; but not natural in the condition of the homeless nomad hunters, among whom totemism arose. For example, we have no reason to suspect that when totemism began men had a highly developed religion of ancestor-worship. Such a religion has not yet been evolved in Australia, where the names of the dead are usually tabooed, where there is hardly a trace of prayers, hardly a trace of offerings to the dead, and none of offerings to animals.24 The more pristine Australians, therefore, do not explain their totems as containing the souls of ancestral spirits. On the other hand, when the Bantu tribes of Southern Africa – agricultural, with settled villages, with kings, and with many of the crafts, such as metallurgy – explain the origin of their tribal names derived from animals on the lines of their religion – ancestor-worship – their explanation may be neglected as far as our present purpose is concerned. It is only their theory, only the myth which, in their intellectual and religious condition, they are bound to tell, and it can throw no light on the origin of sacred animals.

The Bantu local tribes, according to Mr. M'Call Theal, have Siboko, that is, name-giving animals. The tribesmen will not kill, or eat, or touch, "or in any way come into contact with" their Siboko, if they can avoid doing so. A man, asked "What do you dance?" replies by giving the name of his Siboko, which is, or once was, honoured in mystic or magical dances.

"When a division of a tribe took place, each section retained the same ancestral animal," and men thus trace dispersed segments of their tribe, or they thus account for the existence of other tribes of the same Siboko as themselves.

Things being in this condition, an ancestor-worshipping people has to explain the circumstances by a myth. Being an ancestor-worshipping people, the Bantu explain the circumstance, as they were certain to do, by a myth of ancestral spirits. "Each tribe regarded some particular animal as the one selected by the ghosts of its kindred, and therefore looked upon it as sacred."

It should be superfluous to say that the Bantu myth cannot possibly throw any tight on the real origin of totemism. The Bantu, ancestor-worshippers of great piety, find themselves saddled with sacred tribal Siboko; why, they know not. So they naturally invent the fable that the Siboko, which are sacred, are sacred because they are the shrines of what to them are really sacred, namely, ancestral spirits.25 But they also cherish another totally different myth to explain their Siboko.

We now give this South African myth, which explains tribal Siboko, and their origin, not on the lines of ancestor-worship, but, rather to my annoyance, on the lines of my own theory of the Origin of Totems!

On December 9, 1879, the Rev. Roger Price, of Mole-pole, in the northern Bakuena country, wrote as follows to Mr. W. G. Stow, Geological Survey, South Africa. He gives the myth which is told to account for the Siboko or tribal sacred and name-giving animal of the Bahurutshe – Baboons. (These animal names in this part of Africa denote local tribes, not totem kins within a local tribe.)

"Tradition says that about the time the separation took place between the Bahurutshe and the Bakuena, Baboons entered the gardens of the Bahurutshe and ate their pumpkins, before the proper time for commencing to eat the fruits of the new year. The Bahurutshe were unwilling that the pumpkins which the baboons had broken off and nibbled should be wasted, and ate them accordingly. This act is said to have led to the Bahurutshe being called Buchwene, Baboon people – which" (namely, the Baboon) "is their Siboko to this day – and their having the precedence ever afterwards in the matter of taking the first bite of the new year's fruits. If this be the true explanation," adds Mr. Price, "it is evident that what is now used as a term of honour was once a term of reproach. The Bakuena, too, are said to owe their Siboko (the Crocodile) to the fact that their people once ate an ox which had been killed by a crocodile."

Mr. Price, therefore, is strongly inclined to think "that the Siboko of all the tribes was originally a kind of nickname or term of reproach, but," he adds, "there is a good deal of mystery about the whole thing."

On this point Mr. Stow, to whom Mr. Price wrote the letter just cited, remarks in his MS.: "From the foregoing facts it would seem possible that the origin of the Siboko among these tribes arose from some sobriquet that had been given to them, and that, in course of time, as their superstitious and devotional feelings became more developed, these tribal symbols became objects of veneration and superstitious awe, whose favour was to be propitiated or malign influence averted…"26

Here it will be seen that these South African tribes account for their Siboko now by the myth deriving the sacredness of the tribal animal from ancestor-worship, as reported by Mr. Theal, and again by nicknames given to the tribes on account of certain undignified incidents.

This latter theory is very like my own as stated in Social Origins, and to be set forth and reinforced later in this work. But the theory, as held by the Bahurutsche and Bakuena, does not help to confirm mine in the slightest degree. Among these very advanced African tribes, the Siboko or tribal sacred animal, is the animal of the local tribe, not, as in pure totemism, of the scattered exogamous kin. It is probably a lingering remnant of totemism. The totem of the most powerful local group in a tribe having descent through males, appears to have become the Siboko of the whole tribe, while the other totems have died out. It is not probable that a nickname of remembered origin, given in recent times to a tribe of relatively advanced civilisation, should, as the myth asserts, not only have become a name of honour, but should have founded tribal animal-worship.

It was in a low state of culture no longer found on earth, that I conceive the animal names of groups not yet totemic, names of origin no longer remembered, to have arisen and become the germ of totemism.

Myths of the origin of totemism, in short, are of absolutely no historic value. Siboko no longer arise in the manner postulated by these African myths; these myths are not based on experience any more than is the Tsimshian myth of the Bear Totem, to be criticised later in a chapter on American Totemism. We are to be on our guard, then, against looking for the origins of totemism among the myths of peoples of relatively advanced culture, such as the village-dwelling Indians of the north-west coast of America. We must not look for origins among tribes, even if otherwise pristine, who reckon by male descent. We must look on all savage myths of origins merely as savage hypotheses, which, in fact, usually agree with one or other of our scientific modern hypotheses, but yield them no corroboration.

On the common fallacy of regarding the tribe of to-day, with its relative powers, as primitive, we have spoken in Chapter I.

By the nature of the case, as the origin of totemism lies far beyond our powers of historical examination or of experiment, we must have recourse as regards this matter to conjecture.

Here a word might be said as to the method of conjecture about institutions of which the origins are concealed "in the dark backward and abysm of time."