TV Cream Toys Lite

Airfix Kits

Inch high club

Rather like a box of cotton-wool buds that warns ‘Do not insert into ear canal’ and the punter replies incredulously: ‘But what else are they for?’ So it was with Airfix–loudly proclaimed to be ‘display models’ and not ‘toys’, and yet toys they so obviously were. Paint? Bah! We wanted to play with the bloody thing, not wait overnight while the Humbrol enamel dried on the still-unassembled pieces! Even the decals were an annoyance.

But, oh, there’s a word. Decals.

It’s hard to imagine a time when we hadn’t heard of them. A time, perhaps, when we could see an RAF livery without immediately picturing one. A time before we soaked one in a bowl of warm water, slid it off its backing paper and placed it on the wing of a Spitfire or a Wellington Bomber.

For the purposes of this entry, we’re limiting our examination to model planes. Because it was only the model planes that came in such a ridiculously varied range of scales and classes. Because you couldn’t hang a miniature replica vintage Darracq from a piece of fishing line thumbtacked to the ceiling. Because the big ships had annoyingly fiddly tacking rigging and plastic sails.

See also Hornby Railway Set, LEGO, Flight Deck

And because the planes had a truly aspirational hierarchy (which we seem to recall was based largely around the number of moving parts. Pretty much all the model cars had proper moving wheels, but it was only the bigger and badder model aircraft that included moving propellers, rotating gun-turrets and tyres, or fully opening bomb-bays and cockpits). Therefore, they win.

The decals, of course, were one of many hobby-threatening booby-traps designed to scupper your enjoyment, getting forever crinkled or folded before they could be applied properly. Here’s another: polystyrene cement–which could be guaranteed to coagulate into crusty white flakes all over your fingers and tabletop without ever acting as a useful plastic adhesive.1

Worse still was discovering a missing part. You then had to fill out a flimsy form, send it off to Airfix and wait an interminable amount of time for the spare to arrive in the post.2But the biggest disappointment with any Airfix Kit was the huge disparity between the size of the box and the size of the finished model. We’re looking at you, Hawker Harrier.

1 It was also handy for adding an unwanted ‘frosted’ bathroom window effect to the previously clear cockpit covers.

2 Dick Emery, comedian and then president of the Airfix Modellers Club, ran his expanded polystyrene empire in the pages of British comics. In January 1975, he rather excitingly revealed the launch of the company’s new 1:12 scale construction kit of Anne Boleyn. That’ll get ’em gluing, Dick!

Armatron

Programmable robotic arm

While the foreign car factories were laying off staff in favour of this toy’s older brothers, kids across the land were celebrating their new-found ability to remotely move objects around the kitchen table. By twiddling around a couple of joystick levers on the base, Armatron’s various shoulder, wrist and elbow joints could be manoeuvred to pick up anything within it’s admittedly limited reach. In theory. Anything slightly more delicate than the plastic canisters, cones and globes included (an egg, say) would break under pressure between the rubberised jaws, and so any notions of performing David Banner-style laboratory experiments were soon similarly shattered.

Although the lab-coated ginger kids on the box photos hinted otherwise, Armatron was actually intended as a race-against-time game of skill and coordination. Bright-orange ‘energy-level’ indicators on the console acted as a kind of countdown: when the gauge reached zero (‘total discharge’), Armatron turned itself off. Although this probably conserved some of that D-cell battery life, it wasn’t half annoying if you were just seconds away from tightly gripping on to your sleeping cat’s tail.

Armatron was manufactured in Singapore by Tomy and imported by Radio Shack, inspiring loads of knock-off versions in the ’80s.1 A veritable miracle of engineering, it shipped with a single electric motor and a mass of nylon gears and clutches throughout the entire base and arm (as anyone who opened it up would discover). A late addition to the range was the Mobile Armatron, which came on caterpillar tracks (though the remote control wire was only half a metre long). Quite what this added to the game is anyone’s guess.

Robotics enthusiasts delighted in ‘hacking’ the toy (i.e. ‘tricking it out’ with motion sensors or a steam-powered engine), which makes a complete one hard to track down these days. In any case, poorer kids had to make do with the manually ratchet-operated Robot Arm, a Terminator-esque Robot Hand or Robot Claw, each of which–though less impressive–could be secreted up the sleeve of a Parka to aid in the pretence of the owner having been transformed into some kind of futuristic human cyborg. Pop into Hamleys and you’ll find a new version of these going by the name Armatron. But we know the truth.

See also Tasco Telescope, Electronic Project, Slinky

1 Radio Shack eventually acquired the manufacturing rights and re-released the toy in the ’90s under the new name Super Armatron, even though it was mechanically exactly the same.

Backgammon

Pork-soundalike dice ’n’ counters game

There are two reasons why this venerable strategy game leapfrogs those other most austere of board games, chess and draughts, into our list. First, its sheer perverseness. There it was–the backgammon board–always hiding on the other side of the travel draughts, stubbornly resisting comprehension. Not for backgammon the patchwork of squares. Oh no! This thing needed a whole new board with ‘quadrants’ and a ‘bar’ and everything.

Second, the whiff of maturity, the wisdom of ages. Backgammon carried the weight of millennia and, though we didn’t know it at the time, we could sense it. The ancient Egyptians, the Byzantine emperors of Mesopotamia and now us–the great unwashed of suburbia–all staring at the pointy triangle things. At the very least, it proffered a vacant seat at the big table–a proper conversation between adult and child as the rules were explained.

Yet also it was accessible, but not too indiscriminate. Unlike the untouchable ivory chess set in your best mate’s dad’s study, you could get your hands dirty with the backgammon counters. Those green, snot-sleeved draughts players with their petulant ‘crown me!’s kept their distance. Backgammon had a vocabulary of its own: bearing off, kibitzers, the gin position, double bumps and mandatory beavers…Hang on: maybe they were just making this up as they went along after all.

See also Othello, Connect Four, Yahtzee

Oh, and we lied up there. There was a third reason why we wanted a backgammon of our own: the huge surge in popularity it underwent in the 1970s. Rather like snooker in the ’80s and football in the ’90s, backgammon suddenly became trendy. Leading players jetted from tournament to tournament, wrote bestselling books (about backgammon, obviously) and made the front pages in ‘my hotel sex-romp roast hell’ tabloid headlines.1

However, we come not to damn the game but to praise its Cream-era maker. Before Paul Heaton and his mates were a twinkle in a skiffle-humming Hull milkman’s eye, the name ‘House Martin’ was already a stamp of quality thanks to the Hackney-based games factory. Specialising in no-nonsense, phlegmatic renderings of popular post-war games, House Martin unashamedly embossed every box with the legend ‘Made in England’. No wonder they went under.

1 One of Graham Greene’s last novels, The Captain and the Enemy, is about a boy who is won from his father by a con man in a game of backgammon. Possibly one to omit from the bedtime story selection for the little ones, there.

Barbie

Whore next door1

Barbie had been knocking around since the arse-end of the ’50s in one permatanned form or other, but we’re most interested in the so-called ‘aspirational’ late ’80s when manufacturer Mattel realised they could sell the dolls as collectors’ items as well as mere playthings. Or, as the marketing speak of the day put it: to improve profitability and maintain consistent revenue streams, Mattel began a strategy of maximising core brands while simultaneously identifying new brands with core potential. Ah yes! There’s the insipid corporate message at the heart of your Dream Glow Barbie.

But then she’s always been one for the commercial tie-up, has Barbie. From the days of her first-run adverts during the Mickey Mouse Club to Barbie couture and those straight-to-DVD CGI-saturated movies, she’s monetised every innovation, trend and fashion in search of global dominance. In fact, she’d probably use a word like ‘monetise’ without blushing. If she wasn’t wearing so much blusher in the first place.

See also Sindy, Rainbow Brite, Girl’s World

Fair play to the girl, though–always impossibly glamorous and immaculately turned out, Barbie has proved to be a role model to a million all-American, body-conscious Diet Coke heads. And she sure shifts some units, taking upward of three billion dollars over the counter each year.2 What could be more upwardly mobile than that?

As Mattel’s trademarked mission statement solemnly avows, Barbie is ‘more than a doll’. What exactly she wants to be, though, is still unclear. Model, gymnast, fashion designer, rock star–Barbie’s had a punt at every job under the sun, presumably packing each one in after a few days in floods of tears before settling down in front of Trisha with a packet of milk-chocolate digestives ‘consider her options’.3

Call her anything you like, but don’t call her unpatriotic. There is a Barbie doll in a time capsule due to be opened in 2076 to celebrate 300 years of the American Revolution: she is dressed in a stars-and-stripes dress featuring a line of soldiers in uniform on the hem. Cut her down the middle and she’d have the letters ‘U’, ‘S’ and ‘A’ stencilled through her like a stick of rock. Blow her head off and the blood on the wall behind would be red, white and blue.

1 Just as a matter of record, we’d like to point out that no-one at TV Cream thinks that Barbie is a whore (nor, indeed, that she lives next door). We’re just being flippant, based on perceived notions of the doll’s proportions as being just that bit too anatomically unrealistic. Christ, we’re only three words in and already there’s a footnote.

2 Initial profits from Barbie allowed Mattel to become a PLC in 1960. Goodbye garage-based workshop, hello stockholder-pleasing listings on the Fortune 500

3 In recent years, Barbie’s fortunes have seesawed, as she suffered declining sales in the face of the Spice Girl-indebted Bratz dolls.

Battling Tops

Gyroscopic gladiators

Battling Tops? Why, ’tis a grand olde European folk game, sir, as famously depicted in sixteenth-century paintings by Brueghel and his ilk. However, we suspect his Battling Tops weren’t housed in a blue-plastic arena, presumably didn’t go by such wrestling-ring monikers as Super Sam, Tricky Nicky, Twirling Tim, Dizzy Dan or, erm, Smarty Smitty, and certainly were far from Ideal.

Yep! Since 1968, the company that invited you to wind up Evel Knievel had been dishing up more red-plastic crank-powered fun with their repackaging of an old wooden favourite. With defiantly un-medieval box art depicting various ’50s-type kids and their worryingly Barry Cryer-like dad enraptured by the centrifugal tournament taking place under their noses, this was the tabletop arena game to end all tabletop arena games. Wind the spindle with string, give a yank on the starting cord and away you go!

See also Crossfire, Raving Bonkers Fighting Robots, Hungry Hippos

A similar game, Space Attack, was an air-hockey variant on the rotating theme. Crank the red handle with all your tiny might and stop the spinning top being knocked into a trough with a plastic slider. Or, as they put it, ‘Fight off the lightning alien attacks!’ The ‘space’ theme was provided by a piss-poor ‘galactic’ backdrop on the field of play, with a pointless concentric red ring design overlaid. They might as well have written ‘Look, it’s in space, all right? Use your bloody imagination, you ungrateful little sods!’ and been done with it. Ideal at least went the whole hog and–in the wake of Star War s mania–launched a rebranded Battling Spaceships game, which also included some extra, Monopoly-inspired round-the-board progression.

Space Attack and Battling Spaceships shared one gameplay drawback–the frequency with which one of the spinning combatants would be knocked right out of the ring. Frequently the victorious top would be the one that found its way under the radiator, still merrily buzzing away on the lino long after the rest had limped to a standstill.

Although the original is still out there, produced under licence from Mattel,1no additional TV Cream points will be awarded for spotting that this game and its various spin-offs over the years have left us with the legacy that is Beyblades. Now those things really do look like you can take someone’s eye out with them. They’re like Chinese throwing stars. Seriously, they’ve even got ‘blade’ in the name. Why hasn’t someone reported them to Trading Standards?

Space Attack On the rebound

1 You won’t be astounded if we tell you that the arena of this new game is bleedin’ tiny now, will you? This isn’t just a case of ‘the memory cheats’–we know Wagon Wheels and Creme Eggs are the same size and our hands just got bigger. But with these games, they’re deliberately shrinking our childhood!

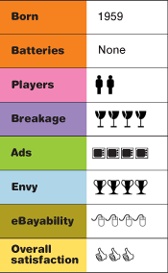

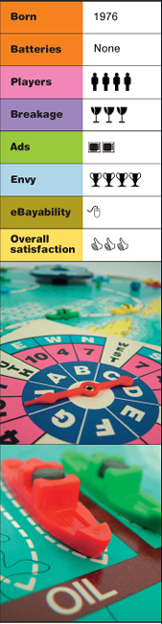

Bermuda Triangle

Makes people disappear

See also Up Periscope, Computer Battleship, Chutes Away

Way before The X Files, back in the mysterious 1980s, part-work magazines such as The Unexplained and telly shows like The Crazy World of Arthur C. Clarke1–he invented satellites, you know–cashed in on our periodic fascination for paranormal phenomena. Strange how, in cycles of almost exactly 20 years, ESP, spontaneous combustion, spoon-bending and all that bollocks inexplicably suckers in an entirely new generation. One might say that the regularity itself is almost…supernatural. Woooo!

Further back in the mists of time, in 1974 to be exact, Charles Berlitz wrote a book called The Bermuda Triangle. Then, in 1981–by complete coincidence–Barry Manilow had a Top 20 hit of the same name. Spooky, huh? In the intervening years, MB had cashed in handsomely with this ships ‘n’ storm cloud ludo variant.

Yet even at a young age, when our experience of triangles was limited to early maths lessons, school band practice and Quality Street,2 we spotted the one thing lacking from this game. The board was square. The cloud was–erm–acoustic-guitar-shaped (and we’d love to have been sitting in on the design meeting for that one). Even the ‘shipping route’ around the game was just some random meandering.

That aside (and ignoring the very fundamental imprudence in setting up a merchant-shipping operation in the middle of an area renowned for strange disappearances), it was a fun game. Move your fleet around the board, trading for bananas, oil, timber and sugar, and try to avoid the ominous, foreboding, magnetic cloud that wants to eat your ships. Simple.

Various ‘spoiler’ tactics could be employed (blocking your fellow players’ ships from each dock), but none was more effective than bribing whoever was moving the cloud to spin it just that bit too fast, thus preventing the ominous ‘click’ of magnet on magnet and keeping you in the game for another go. Many Top Trumps and sticker collections would unaccountably vanish under the table when the Bermuda Triangle rolled into town.

Incidentally, theories that the strange occurrences of the real Bermuda Triangle are caused by aliens sucking boats and planes out of the sky with giant magnets have not yet been disproved. But then, as the great Arthur C. Clarke himself said, ‘Your guess is as good as mine.’3

1 You must remember it, surely? No? Oh, alright, it was actually called Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World, but we’d love to have seen the auld fella fetch up on Top of the Pops singing ‘Fire’. That would’ve been fab!

2 The green ones. You can also buy posh chocs in triangle-shaped boxes Toblerone doesn’t count–technically, it’s a prism.

3 He’s the president of the H.G. Wells fan club, you know.

Big Trak

Futuristic battle tank and apple cart

See also Star Bird, Speak & Spell, Armatron

Resembling nothing more than a vehicle from Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons redesigned by Clive Sinclair, Big Trak was controlled, as the presenters of Tomorrow’s World breathlessly related, by that all important ‘silicon chip’.1 With just a few taps on the keypad, this fully programmable beast could be instructed to move and turn in different directions, fire up its ‘photon canon’ and make a couple of modish electronic noises. It was, of course, used mainly to frighten the family pet. Pretty good value for £20.

The novelty was that it was ostensibly capable of navigating a path around cumbersome household objects–assuming no-one had actually moved any of them while you were busily punching in the required sequence of movements–usually a case of trial and error. Big Trak worked best when its route avoided shag-pile carpet, inclines and anywhere outdoors. According to the manual, programming distance travelled was calculated in noncommittal units of ‘roughly 13 inches’, while the angle of rotation ‘may not be enough to make the turn you want. Or it may be too much.’ You want vagueness? MB Electronics delivered it in spades (which themselves were probably of wildly indeterminate size).

Used in conjunction with the Big Trak Transporter (yours for only another £15), Big Trak was rumoured to be able to ferry objects around the house–maximum load: ‘about one pound’.2 Promised innovations that never materialised were voice synthesis and additional accessories (there was a mysterious unassigned keypad button marked ‘IN’ on the keypad for just this purpose).

Not to be outdone, Kenner Toys came up with Radarc, another twenty-first-century-esque remote-controlled tank. The gimmick with Radarc was that, instead of being programmable, it was operated by ‘muscle control’–a radio transmitter that strapped to your forearm, with buttons on the inside that made contact as you worked your hand and wrist (stop sniggering at the back!).3

However, with six chunky traction tyres, sticky labels ‘to add exciting detail’ and a camp little signature tune that played before and after every, erm, motion, Big Trak was much coveted and seldom seen–the dictionary definition of toy envy.

1 A 4-bit Texas Instruments TMS1000 microcontroller running at approximately 0.2 MHz, chip fans. That’s just 64 bytes of RAM to you.

2 A fabulously complicated and tortuous process for carrying out otherwise simple household tasks? Clearly this was a toy aimed at men.

3 There was also TOBOR, a robot from Schaper that looked like a cross between R2D2 and Darth Vader, was operated by a ‘transmitter’ that was nothing more than a tin clicker, and was utterly defeated by any carpeted surface.

Big Yellow Teapot

It’s big and it’s yellow, but there’s no tea in it

Now-defunct toy manufacturer Bluebird was founded on two very solid principles. Small girls like doll’s houses. Small girls also like plastic tea sets for serving cups of invisible tea to their dollies.1 Then someone fell into a filing cabinet at the office Christmas party and came up with the bizarre idea of crossbreeding the two. Yes, this was a doll’s house, but made of yellow plastic and shaped like a huge teapot.

Why was this? No reason was ever given. The house was inhabited by small plastic peg-like people (somewhere between stunted Playmobil folk and Weebles without the wobble) with welded-together legs, all the better to slide them down the chimney or make them ride round and round in the roundabout-cum-teapot lid (the latter 20 seconds of entertainment–lots of fun for everyone’–also forming the most memorable moment of the accompanying ad). This delightful pied-à-terre was furnished throughout with a small quantity of monolithic red and blue teacup chairs and tables, with the further appointment of additional decor simply printed on cardboard walls (where it floated slightly above the floor in an unconvincing fashion).

See also Weebles, My Little Pony, ‘A La Cart Kitchen’

A rival effort came courtesy of Palitoy, whose Family Treehouse obeyed the same basic design principles and yet had the added bonus of a trunk-based elevator (which presumably attracted a better class of tenant than the average council-estate teapot). Another was Matchbox’s School Boot, adding a whiff of academia to the old ‘woman who lived in a shoe’ routine and thus robbing it of much appeal, although there was at least a variety of playground-themed accessories.2 Live-in chimneys and pumpkins caught the tail end of the trend.

Basically, Big Yellow was a doll’s house for the Duplo generation: those who required everything to be large, unbreakable and safe to chew, yet were still innocent enough to refrain from shoving the little plastic people down (or up) the cat for a change (or indeed, trying to create a teapot tropical monsoon by actually pouring boiling water on them).