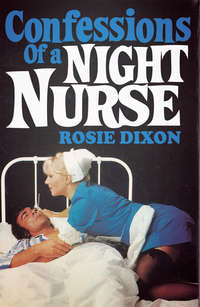

Confessions of a Night Nurse

“Hoity-toity,” sneers Natalie.

“In order to avoid more bloodshed I think it would be a good idea if we started cleaning opposite ends of the house,” I say with commendable self control. “May I suggest that you tackle the so appropriately named tool shed—if it is still standing?”

Mum and Dad are due back on the Sunday afternoon and Natalie and I hardly exchange more than a few words up to that time. However, I do see Mrs Wilson. I am standing in one of the dustbins trying to force the rubbish down and make room for some more bottles. She takes one look at me, over the fence, shrugs, and says “That’s the best place for both of you.”

By the time I have opened my mouth she has gone inside her house and slammed the back door. There is obviously little point in expecting any sympathy there.

“Do you think we ought to go to the station?” I ask Natalie.

“And get a train out of the country?”

“No, stupid. Meet Mum and Dad.”

“You can never be certain what train they’ll catch. We don’t want to miss them and find them having a long chat with Mrs W. when we get back.”

“True. We’d better stay here, then. Do you think the place looks all right?”

“It’s difficult to say. I know where all the stains and scuff marks are, so I notice them more easily than the average person might.”

“I hope you’re right. The trouble is that Mum isn’t the average person. After six days away she and Dad are going to come through that door like they’ve got to find six deliberate mistakes in sixty seconds.”

For once Natalie and I share a common emotion. It is expressed in a shiver of terror.

It is half past four when Mum and Dad pause at the gate and look at the garden as if they can’t believe their eyes. I remember the time because a film called A Farewell To Arms had just ended and I am still brushing away the tears. It is about this nurse who falls in love with a soldier at the front. You know—where the fighting is. They make love in his hospital bed and she gets pregnant and dies in childbirth just as they are going to cross over into Switzerland and safety. It is so sad that I cried buckets. The bloke was Rock Hudson and it really made me feel what a wonderful job nurses do.

While I am trying to compose myself, Natalie rushes to the front door and throws it open. “Hello, Mumsie!” she cries. “Did you have a lovely time?”

“Quite nice, thank you, dear,” says Mum.

Dad is still gazing thunderstruck at the garden. “Where are all the flowers?” he says.

“The milkman’s horse got up on the pavement, Dad.”

“He got it out of retirement, did he? He’s had a van for five years.”

“Vandals,” I say. “There’s been an awful lot of trouble while you’ve been away. Look what they did to Mrs Wilson’s lawn.”

“Blimey. I thought it was an open cast coal mine. You told the police, have you?”

“They know all about it,” says Natalie truthfully. “What was the weather like, Dad?”

Dad carries the suitcases into the house. “Diabolical. The worst we’ve ever had there—the worst we will ever have there. I’m not going back. Holiday? It was more like six days in a prisoner of war camp.”

“Where’s my coat?” says Mum, looking at the hallstand.

I am just thinking that it must have been nicked and wondering what to say when the telephone rings. I know instinctively who it must be, but before I can move Dad picks up the receiver.

“Hello? Oh, hello Mrs Wilson.” He puts his hand over the mouthpiece. “It’s Mrs Wilson. Stupid old bag. What on earth can she want?”

“I’m going upstairs,” says Mum.

Ten minutes later Natalie and I are in the front room with Dad who now knows what Mrs Wilson wanted. He has turned a strange blue colour and his hands are shaking. “Now listen, you two,” he says. “I’m going to—”

At that moment Mum comes in. She, too, is looking strained and holding something in her hand. “I was doing the unpacking and I noticed these stuffed down the end of our bed,” she says. “Whose are they?”

She is dangling a pair of bright yellow men’s underpants which, with a shiver of distaste, I remember covering Flash’s vulgarly large private parts. Natalie bursts into tears.

“Were people using our bedroom?” snarls Dad.

“Oh Rosie, why did I ever listen to you?” sobs my deceitful little sister.

“Right. You go outside with your mother. I want to speak to Rosie.” They are hardly out of the room before Dad lets fly. “What you’ve done is a bloody disgrace! You’ve disobeyed your mother and you’ve blackened our name amongst the neighbours—I understand you’ve even had the police round here. The house is like a pigsty and I shudder to think what went on.”

“Dad—”

“Shut up! When I want your interruptions I’ll ask for them.

“What I am most disturbed about is the effect your behaviour is having on your sister. She is at a very formative age and the kind of carryings on you go in for could be a blooming disaster as far as her moral standards are concerned.”

“Dad—!”

“Shut up!!! You must realise that, being older than her, you have to set some kind of example. Supposing she starts imitating your behaviour?”

“It’s not fair, Dad. I always get the blame for everything. Just because she’s younger than I am you seem to think that butter wouldn’t melt in her mouth. Well, I’ve got news for you—”

“And I’ve got news for you, my girl. I want you out of this house just as soon as you can find a job to support you. I think you’re a bad influence on your sister and it’s much better if the two of you are kept apart.”

For ten seconds after he had finished speaking I am on the point of telling my father a few home truths about my sweet little sister; and then my mind soars up to a higher plane. I see Doctor Eradlik walking down a long white corridor, a look of stoical self-sacrifice etched across his beautiful features. I see Jennifer Jones approaching Rock Hudson’s bed. I have arrived at a decision.

“Very well, Dad,” I say calmly. “I can tell you what I’m going to do, now. I’m going to be a nurse.”

Three and a half weeks later I have been summoned to an interview with the matron of Queen Adelaide’s and Dad and the family are just beginning to understand that I meant what I said.

Dad, particularly, finds it difficult to believe that any hospital would be prepared to consider me. He has an idea that nurses are somewhat like nuns and unlikely to be accepted if they have so much as caught a glimpse of an unpeeled banana. He also reckons that you have to be of noble birth and watch BBC 2 as well as have it.

“You’re not going to tell me that all those black nurses are princesses,” says Mum.

“I don’t know so much,” says Dad. “A lot of those blackies you see on the telly are better dressed than white people.”

“You don’t watch those,’ says Natalie. “You watch the ones with the bare titties doing the conga.”

“Natalie! Watch your language, please!” Mum looks horrified.

“We all know where she gets that from, don’t we?” Dad fixes me with his beady eye and I would like to bash him over the nut with Natalie.

Raquel Welchlet is the one who continued to be most surprised by the way I stick to my resolve.

“I never reckoned you were serious,” she says. “I thought you were just doing it for effect. Like when you read that book about air hostesses.”

“Air stewardesses,” I hiss. “Hostesses are people who work in nightclubs.”

“Those stewardesses spent all their time in night clubs if that book was anything to go by.”

“Well, nurses don’t spend all their time in night clubs so you needn’t start fretting about my eyesight.”

“I don’t think you’ll be able to stick it even if they do accept you. They work terribly hard, you know.”

“But it must be rewarding, mustn’t it?”

“The pay’s lousy from what I can make out.”

“I didn’t mean that.” Natalie is about as sensitive as a clay tuning fork. “I meant that it must be satisfying to nurse people back to health.”

Natalie sniffs and shakes her head. “I don’t like sick people.”

“It’s people like you that give being healthy a bad name,” I tell her.

Mum is merely realistic. “Do what you like, dear, but make sure you don’t catch anything.”

Queen Adelaide’s is a big disappointment after Mount Vista on the Doctor Eradlik show. It is a huge hospital but it looks as if it was carved out of charcoal and then had a giant vacuum cleaner bag emptied over it. What I at first imagine to be its grounds turn out to be the public park next door. As I go through the swing doors two nurses are coming out. They are wearing red cloaks with blue linings and talking in upper class voices.

“Stupid little bitch thought your sternum was what you sat on,” says the first.

“Oh no!” The second one’s voice screeches into the air like a rocket. Dad would love them.

Just inside the door is a pigeon hole behind which sits a pigeon wearing glasses. She coos softly to herself when I say that I have an appointment with matron and shuffles through a pile of papers.

“Rose Dixon?” She rises up slightly and leans forward as if she is wishing to confirm that I have brought the lower half of my body with me. Apparently satisfied, she sinks back and gives me totally unmemorable directions of which I can recall no more than that I have to go to the third floor. I am frightened to ask her to say it all again unless I immediately give the impression of being hopelessly stupid—just like the girl the two nurses were talking about. Who knows? The directions might be part of some cunning test to check on my memory.

I get into the lift and, for some reason that I will never understand, press the button marked four. I immediately press three but the lift glides contemptuously past my destination and stops at the fourth floor. The doors slide open and I am faced by an old man in a wheelchair and a nurse who is escorting him. He is wearing a dressing gown and seems half asleep. The nurse has no sooner pushed her patient into the lift than she slaps her hand to her forehead.

“Jesus, but it’s a fool that I am. I’ve gone and left his records in the ward. Hang on here for a moment, will you?”

Before I can say anything she has disappeared down the corridor. My presence on the fourth floor must suggest to her that I am a member of the hospital staff.

She has pressed the “door open” button but no sooner has she padded off than the patient’s eyes open a quarter of an inch, rather like those of the crocodiles you see in all those nature films on the telly. I am probably being very unkind comparing him to a crocodile because he looks quite a sweet old man. He is smiling at me now.

“She’ll be back in a minute,” I say comfortingly. It is all rather nice because I feel like a nurse already.

“Get your knicks off!”

Before I can be certain that I am hearing aright the old man has pressed the button marked B for Basement and the doors are closing.

“Please! We must wait,” I yelp.

“We’ll go down to the boiler room and stimulate each other on the coke,” says the sprightly greybeard. “You don’t mind a few pink patches on your bum, do you?”

“I’ve got to see Matron!” The lift sinks below the third floor.

“Don’t waste your time. She’s the ugliest woman in the hospital.” He suddenly propels his chair across the lift and pins me against the wall. “Come here! I want to take handfuls of you.”

He is a man of his word, too. When I come to think about it he must be both the oldest and the dirtiest man that I have ever met.

“Stop doing that!” I squeal, thinking that his sense of direction has not faltered over the years. “You must pull yourself together!”

“Up guards and at ’em! I’m eighty-four and I could show you young girls a thing or two.” He whips open his dressing gown and once again proves his point. I must say that though it distresses me to look at his equipment it is certainly more ramrod than shamrod. The door slides open and I catch a glimpse of an amazed man in shirt-sleeves leaning on a shovel. Hurriedly I press the button for the fourth floor.

“You were in the army, were you?” I humour the wizened octogenarian.

“The Gold Coast. That’s where you get them. Big, wobbling titties wanging against your belly. That’s the stuff to give the troops, eh?”

“It’s very nice,” I say appeasingly. “But don’t you think you ought to put it away now?”

“I know just where to put it away. It won’t keep, you know. They don’t.”

What a very lively old man, I think to myself. I bet he has more than a glass of Lucozade for elevenses.

“You’ve got a firm bosom, my dear.”

“Thank you. Can I have it back now?” For a senior citizen he certainly has very strong fingers. I can hardly prise them off my sweater.

The doors slide open on the fourth floor and there is an astonished nurse blinking at us.

“What happened to you, Mr Arkwright?”

Greybeard shrinks into his wheelchair and half closes his eyes.

“She tried to elope with me, Nurse Finnegan.”

“He went mad the minute you disappeared,” I say lowering my voice discreetly. “He started mauling me and suggested we made love in the boiler room.”

Nurse Finnegan looks at me in a way that might be described as strange.

“She pressed the button, Nurse.”

“You wicked old man.” I round on him so fiercely that Mr Arkwright sinks even lower into his chair. Nurse Finnegan is looking at me suspiciously.

“You don’t nurse here, do you?”

I give her the famous Rosie Dixon smile. “Not yet. I’ve come to see Matron.”

“What were you doing on the fourth floor?”

“I pressed the wrong button.”

“Don’t leave her with me, Nurse Finnegan,” croaks Arkwright pathetically.

“Hasn’t he done this before?” I whisper.

“They call him Mr Sunshine,” says Nurse Finnegan gazing at me with obvious suspicion.

“Bengers Food,” murmurs Mr Arkwright, closing his eyes.

Nurse Finnegan does not let me out of her sight until she sees me knocking on Matron’s door. I can’t blame her in the circumstances but I wish there was some way of repaying that horrible old man. I am still thinking about my harrowing experience when an upper class voice rings out from the other side of the door. “En-ta!”

I go in and find myself in the presence of a woman who makes Hattie Jacques look like Twiggy’s kid sister. She is sitting behind an antique desk signing papers.

“Miss Dixon?” She does not look up.

“That’s right.”

“My staff address me as matron.”

For a moment I think she is supplying me with some interesting information for my scrap book. Then I cotton on. “Yes, Matron.”

“That’s better. Now, where have you been? I was told you were coming up and then you disappeared for ten minutes.”

“I got lost, Matron.”

“Lost?” Matron looks up at last. “Good gracious. When I look at you I would find it easier to believe that you had been assaulted.”

“Well, actually—” And then I stop myself. Even if she believes that I was attacked by a sex-mad geriatric she will probably think I egged him on. Either way it is not going to make a very good impression.

“Actually, what?”

Matron has enough hair on her upper lip to clog a moustache cup and when she moves, the starch in her uniform crackles like an icy pond breaking up—at least, I imagine it is in her uniform.

“Nothing,” I say.

Matron gazes down her nose towards a bosom that looks like a ruckle in a barrage balloon. “I think I should make it absolutely clear at the onset that I am a stickler for smart turn-out. The discipline required to make sure that one is a credit to oneself and the hospital carries over into one’s attitude to one’s job and inspires confidence in the patients. By arriving here as if you have just been dragged through a hedge backwards you have not taken that first step towards reassuring me that you have the right attitude of mind to become a nurse.”

“I’m afraid my appearance is due to my confusion at losing my way,” I grovel.

Matron gazes up towards the ceiling and sighs. “No matter. The golden days are past. We must be thankful for what we can get.”

“Amen,” I don’t know why I say it. It is just that she drones on in such a way as that I imagine I must be in church.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Granted.”

“What?! !”

“I mean, granted, Matron.”

Matron shudders and her moustache quivers as if a strong wind has just run through it. “I have a horrible suspicion that you are trying to mock me, Miss – er Dixon.”

“Oh no, Matron.” What is the old bag on about?

“Tell me, Miss Dixon.” Crackle, crackle goes Matron’s uniform. “Does your family have a nursing background?”

“I think my father had his tonsils out.”

“No, Miss Dixon.” Something seems to be causing Matron pain. Maybe her cap is on too tight. “What I meant was do you have any relations who have worked in the medical profession?”

“My Aunt Gladys used to work in Boots during the war.”

Matron’s eyes are now tightly closed. “Fascinating. It says on your curriculum vitae that you have one ‘A’ level. What is that?”

I shake my head. “I’m sorry, Matron. I don’t know.”

“You don’t know what ‘A’ level you’ve got?”

“Oh, I see. I thought you meant what does curriculum vimto mean. I’ve got geography.”

“Geography.” Matron shrugs. “It could have been woodwork, I suppose.”

“Not really,” I say, hoping I don’t appear too pushy. “We didn’t do woodwork after ‘O’ levels.”

Matron closes her eyes again. “Of course.” She shudders and then addresses me in a firm brisk voice. “Now, Miss Dixon, I don’t have to tell you that nursing is a hard, arduous profession. You have to dig deep and conscientiously to find jewels. Many girls—” she shakes her head sadly “—just can’t take it.” She looks at me expectantly and I can see that she is hoping that I will speak up and show her that I am not the wilting type.

“I know what I’m letting myself in for,” I say.

Matron nods. “Sometimes it’s a good idea if a gel faces up to the facts right at the onset and realises that she isn’t cut out for the life. Long hours … mental and physical strain … the requirement to study while you work… .” Her voice dies away and she smiles sympathetically. It is the first time I can remember her smiling.

“That’s what everybody says to me,” I tell her.

“Y-e-s.” Matron speaks slowly and thoughtfully. “That’s never worried you? I mean, you think you would be able to cope all right?”

“I’m no stranger to stress,” I tell her. “I used to work on the check-out at Tescos. Of course it was Saturdays only because—”

“We have what we call a four weeks trial period at Queen Adelaide’s.” Matron obviously takes in what you say to her very quickly. “It’s a safety precaution on both sides. During that time a nurse is able to see if she likes the life and—” Matron pauses dramatically “—we are able to see if we like her. Should we find that we are suited to each other, training proceeds, with preliminary examinations after one year and the majority of our gels becoming fully qualified State Registered Nurses after three years.”

I give her my cool, efficient nod and tuck my blouse back into the top of my skirt—ooh! I would like to take away that old man’s false teeth and feed him toast. Matron crackles and gives me another smile. “You’re not intimidated?”

I think hard for a minute and then shake my head. “I don’t think so. I’ve had a polio jab, though.”

Poor Matron. There is no doubt that she is in pain. Probably some tummy upset due to all the strains and stresses of the job. “We will be writing to you in due course. Thank you for coming to see me and for expressing your willingness to indulge in life’s noblest work.”

For a moment I think she is going to stand up but she just crackles and goes back to signing papers. The interview is presumably over. Short and sweet. It could have been worse. I win another brisk nod when I fall over a chair and then hobble out into the corridor. There is no sign of Mr Arkwright but I go down by the stairs, just in case.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книгиВсего 10 форматов