Pretty Iconic: A Personal Look at the Beauty Products that Changed the World

Its woeful misuse was and is a terrible shame, because when used judiciously and sparingly as an undercoat for concealer or as a straightforward highlighter, Touche Éclat is actually rather wonderful. Its revolutionary click pen packaging makes it very convenient for making up on the move (you’ll need to wash the brush regularly, of course), its thin formula blends beautifully, and its sparkle-free light reflection is perfect on brow bones to sharpen their appearance. On cheekbones, or applied lightly across the centre of the face in a cat’s whiskers formation (then blended, of course), it can bathe skin in gloriously flattering light.

Sadly, my appreciation for Touche Éclat came way too late in the day. I am horribly allergic (and I say this as someone who, after a lifetime of product testing, has skin as hardy as Shane MacGowan’s liver), and so I cannot finally make amends for my former harshness. I use Bobbi Brown or Becca corrector on my own dark circles. But to the vast majority of women who can click, sweep and blend Touche Éclat with no adverse effects, all I can say is that I finally see where you’re coming from.

Avon Skin So Soft

I do so love a product with a sneaky sideline in something for which it was never designed. KY Jelly as a hair styler on short retro haircuts, non-oily eye make-up remover on stubborn carpet and soft furnishing stains, and clear nail polish on freshly laddered tights are just a few hugely satisfying deployments of products entirely fit for multiple purpose. Perhaps the most polymathic product of all is this, a cheap-as-chips fragrant body moisturising spray, reportedly used for decades by the US Navy as a standard-issue mosquito spray for soldiers stationed abroad. Meanwhile, on Civvy Street, Skin So Soft’s vast legion of fans (40 million bottles have been sold since its 1961 launch, and Avon representatives stockpile it at the beginning of every summer) claim the dry-oil spray makes an excellent remover for candlewax, chewing gum and paint. Artists and decorators use it to clean brushes, housekeepers swear by it to remove carpet stains, and Hollywood film crews douse themselves in large quantities before entering an insect-ridden shooting location. Even the royal household is rumoured to use it for purposes on which we can only speculate.

What we can be sure of is that Skin So Soft is a hidden gem of a product, and that to have this somewhat dated and naff-looking bottle (more like something kept under the sink than in the bathroom cabinet) handy at all times is to be in on an immensely satisfying secret. So wide is Skin So Soft’s skill set that it’s easy to forget that it delivers admirably on its original brief. It has a light, pleasant smell, a non-greasy texture, and leaves limbs softened and more evenly toned. And mercifully abhorrent to mozzies.

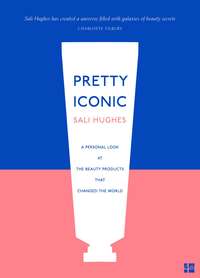

Elizabeth Arden Eight Hour Cream

I admire beauty brands with a sort of benign arrogance about their star products, a self-belief so strong that to tweak, reformulate or move with the times would be an unthinkable admission that any improvement on the original is even possible. This is why I so admire Elizabeth Arden’s Eight Hour Cream, a thick, glossy, greasy preparation invented in the 1930s by Miss Arden herself and used ever since on the burns, cuts, windburn, chapping, grazes, dry lips, ragged cuticles and unruly brows of humans, and on the aching legs of thoroughbred horses (yes, really – Miss Arden always kept jars in her stable and it caught on. I suppose if you’re dropping half a million on an animal, then twenty quid on some luxury hoof ointment is mere loose change).

But modern beauty fans will know 8-Hour less as a medicinal balm, more as a multi-purpose gloss quite unlike the rest. While other paraffin-based products like Vaseline become thin and slide gradually off the skin or into the eyes, 8-Hour remains thick, holds its gel-like structure well and tends to stay firmly (and stickily) on the job. This makes it peerless in changing the consistency and finish of all manner of traditional cosmetics. Make-up artists mix it with powder shadows to create eye gloss, with kohl to make brow wax, with lipstick for a sheer lip gloss or gleaming flush of cheek colour. But this is no industry secret. It’s by far Elizabeth Arden’s most successful product, with a tube of the original formula (as opposed to its many spin-offs) selling every thirty seconds worldwide. Millions of women, including Victoria Beckham, Penélope Cruz, Emma Watson and Kate Moss, use 8-Hour neat to add a flattering sheen to cheekbones and lips, softening the skin and adding a very subtle pinky-peach tint. I see 8-Hour primarily as cosmetic, but I don’t quibble with its skincare benefits in certain applications – the mild beta hydroxy acids slough dead skin flakes, particularly on the mouth and nose – while the vitamin E and paraffin provide temporary moisture and relief.

Those who love 8-Hour seem never to be without a tube in their handbag, ready for emergency deployment, and will suggest its use in seemingly any skin crisis or extreme weather condition. It provides an almost unmovable barrier of emollient and for this reason, many women even swear by 8-Hour for basting the face in readiness for long-haul flights, though some of us really wish they wouldn’t; the smell is a pungent and not universally pleasing combination of roses, lanolin, a nana’s handbag and Germolene. The relatively new unscented version – though by no means odourless – is a tad more sociable, if a little inauthentic.

Lush Bath Bombs

To the young or disinterested, bath bombs must have just appeared from nowhere, piled high in Lush shop windows, their distinctive and sometimes obnoxious smell polluting the air for fifty yards. But for me, bath bombs will always be a reminder of Cosmetics-to-Go, Lush’s innovative forerunner in Poole, Dorset. This was the first incarnation of Lush, founded in 1987 by husband and wife Mo and Mark Constantine and beauty therapist Liz Weir, selling natural, British-made and faintly bonkers products like solid shampoo bars, fresh fruit-enzyme face masks hand blended on the premises like smoothies, peanut butter face scrubs that were literally good enough to eat, and Second World War-inspired liquid stockings in glass bottles that looked like Camp Coffee. Like the Body Shop’s errant, less neurotic little sister (the Constantines had invented many products for Anita Roddick’s fledgling empire, including its bestselling Cocoa Butter Hand & Body Lotion), Cosmetics-to-Go was the first time I’d seen beauty with both a sense of humour and a strong sense of purpose.

A cruelty-free stance was at the heart of the brand, without it becoming so worthy and earnest as to be dull. Quite the contrary: I looked forward to new Cosmetics-to-Go catalogues like new issues of Just Seventeen, and pored over the quirky illustrations and chatty copy. I’d then ring the order line whenever I had a spare couple of quid, and two days later, a brown paper-wrapped box covered in primary-coloured labels would arrive, crammed with truly groundbreaking and extraordinarily packaged products. Eyeshadows in faux-marble wedges, popped in a Camembert box to create a bespoke palette not a million miles from a Trivial Pursuit wheel, a men’s grooming range festooned in chintzy florals when everyone else was flogging aftershaves got up to look like car parts, and a blackberry-scented bath powder moulded to look like the kind of Acme bomb beloved of Wile E. Coyote. This was the first ‘bath bomb’ – a fizzing mix of fragrance, essential oils, moisturising butters, citric acid and bicarbonate of soda, directly inspired by the uplifting, soothing qualities of Alka-Seltzer. Its relative cheapness and versatility spawned a whole range of bombs in multiple shapes, colours and scents, and an entirely new product category was born.

Ultimately, Cosmetics-to-Go had too many brilliant and impractical ideas, too little business acumen. Even as a child, I wondered how they could possibly be making enough money when, as a matter of course, they’d mistakenly send me free duplicates of practically every order I placed. They weren’t, as it turned out. Cosmetics-to-Go went down the plughole in 1994, but their bath bombs stayed afloat, providing the old CTG team with a basis for new venture Lush, now a hugely successful British high street retailer based on the same environment/employee/animal-friendly principles as before. Lush still makes dozens of different bath bombs (selling well over 26 million of them to date), all copied endlessly by rivals, often with much less care for quality and ethics. Even when the real thing enters my house via press sample, kid’s birthday gift or party bag, my heart sinks in anticipation of post-bath scrubbing to remove some glittery lurid puce tidemark. But I always give in to the pleas and chuck one in because I want my kids to see that modern beauty products aren’t only for making someone’s nose look skinny on Instagram. They can also be fun, kitsch, bonkers and kind. No one demonstrates that better than Lush. Long may they fizz.

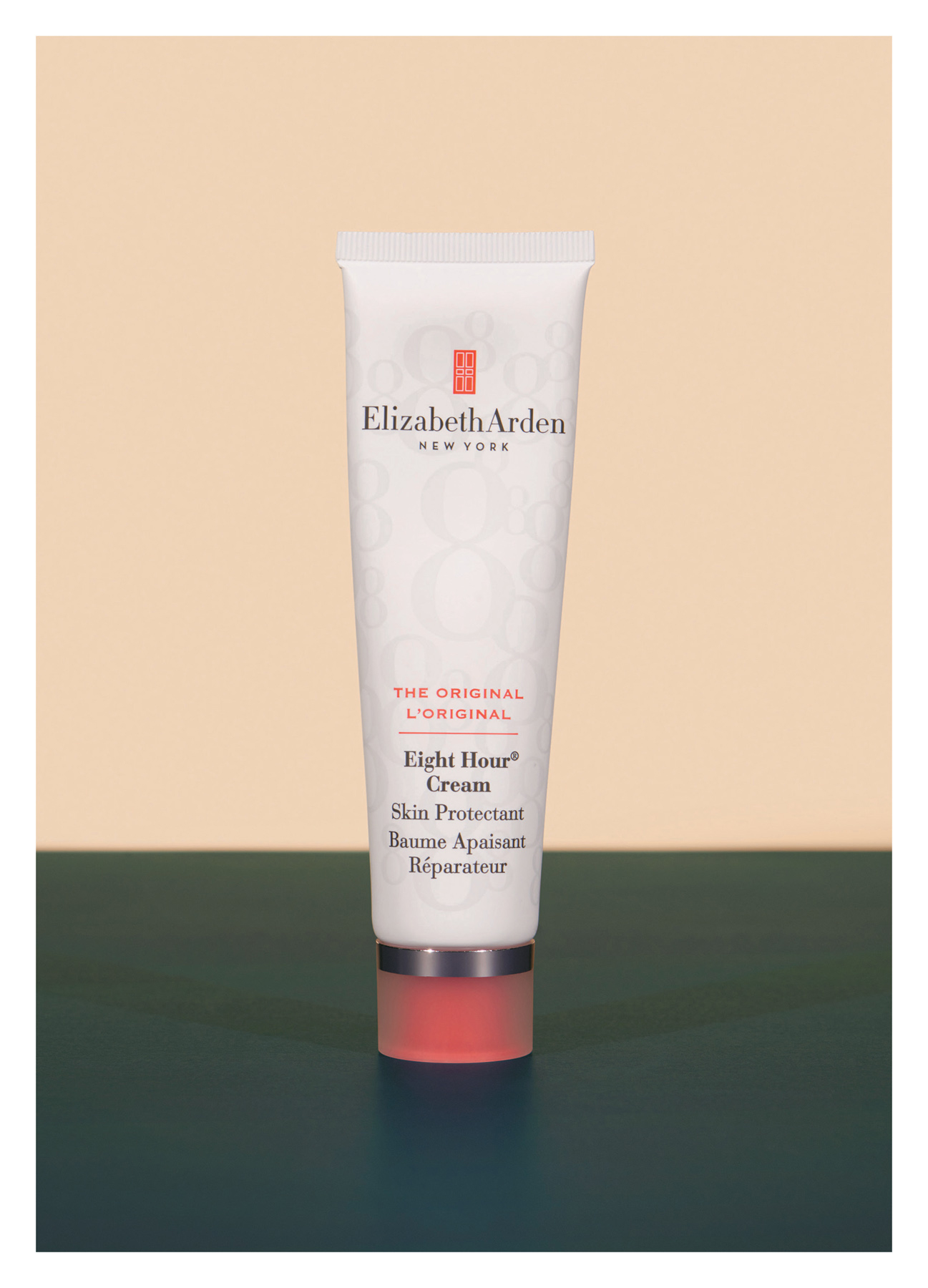

Kent Combs

Any company awarded a Royal Warrant – a recognition of excellence for selected small firms that supply the royal households – must be doing something right. A firm granted Royal Warrants by nine successive sovereigns, though, can claim quite persuasively to be doing pretty much everything better than anyone else. Founded in 1777, the brush-making concern G.B. Kent & Sons was awarded its first warrant by George III and has received royal thumbs-up from every king and queen since. Kent, the UK’s longest established brush-maker, is a heart-swelling example of a firm peopled by artisans, preserving specialist skills in the face of mass production and foreign imports.

Kent allies British pluck and ingenuity – the Second World War saw the firm produce a shaving brush with a secret compartment for map and compass to facilitate the escape of prisoners of war – with meticulous production methods to produce doughty, tactile artefacts of enduring loveliness. Its saw-cut combs are polished and buffed by hand, the teeth free of the tiny, snaggy ridges found in injection-moulded combs. The women’s tail comb – a seventies classic that sells a pleasingly un-mass-market forty a day – is a sleek, frictionless delight that makes you want to keep on combing, mermaid-like, long after the practical necessity has gone. I like to imagine Princess Anne using one to tease her crown before sweeping everything into a no-nonsense riding bun, or Charles reaching for his Kent brush in the hope of making his remaining strands go further.

If sharing a brush supplier with the Queen doesn’t float your royal yacht – and I do understand – focus instead on the preciousness of British-made beauty tools, made with love, pride and devotion to the craft, and sold widely at a very reasonable and accessible price point (my paternal grandfather always carried a tortoiseshell Kent – and he was a lowly stable lad). Kent is a company I wish to exist for ever. We should never assume that’s a given, and perhaps replace our old combs forthwith.

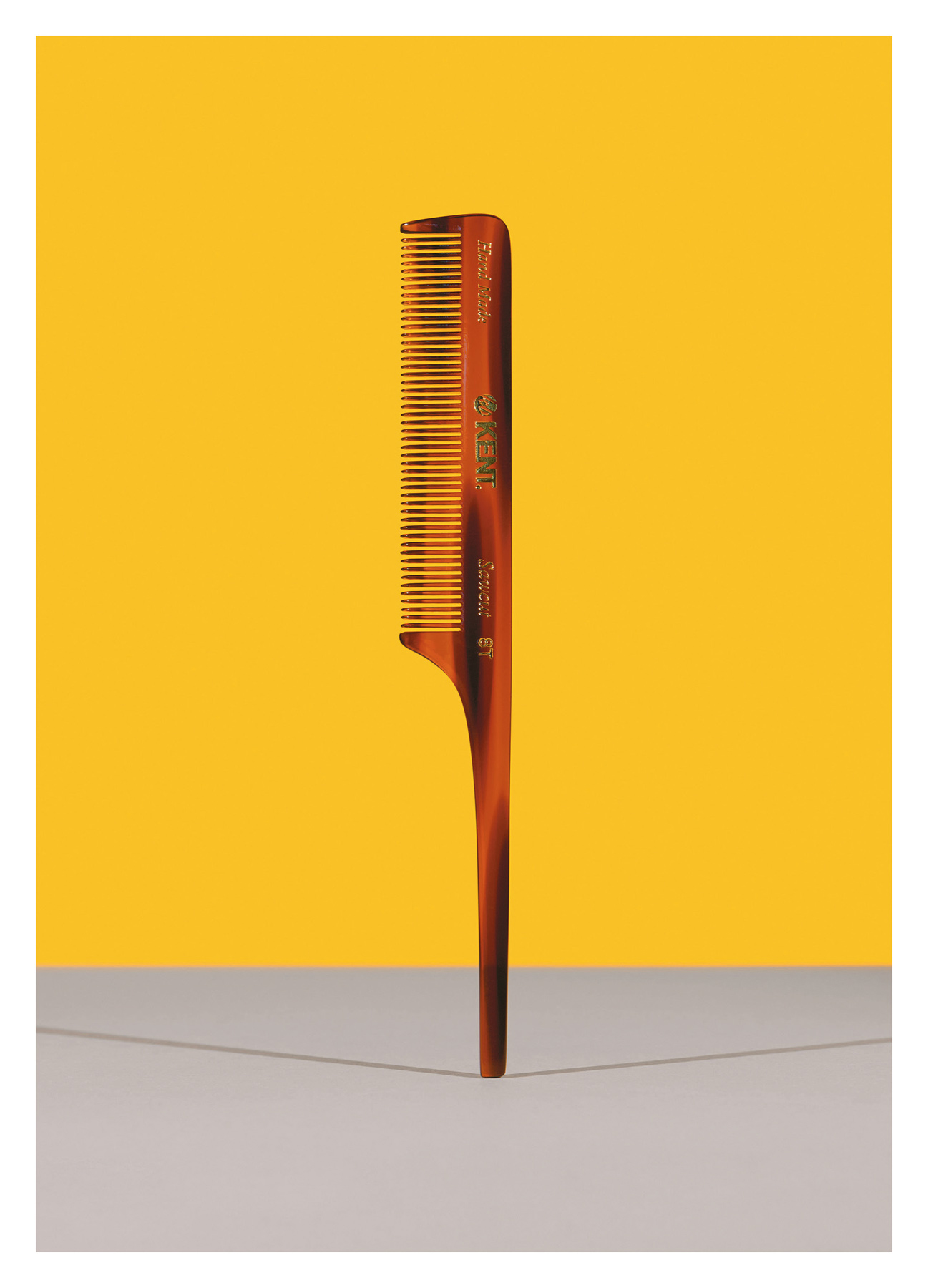

Shu Uemura Eyelash Curler

In the eyes of critics, perhaps no product better sums up the madness of beauty than the eyelash curler. Here is a prohibitively dangerous-looking piece of metal that resembles something a Victorian dentist might use to winch out a rotting molar, used for the sole purpose of lifting and curving one’s eyelashes temporarily. It does seem slightly bonkers, on reflection. And yet, with the right curler, it really is a uniquely gratifying twenty-second job.

The Shu Uemura eyelash curler is such a reference point for all other beauty tools, that it’s easy to forget that it only launched in 1991. When Japanese make-up artist Shu Uemura launched his groundbreaking eponymous brand, there were few luxury lash curlers on the market and he felt all of them failed to sufficiently and comfortably curl short lashes. And so he briefed his son Hiroshi Uemura to create one that did. Hiroshi worked with professional make-up artists to test different widths, lengths, gradient curves, rubber elasticity and pressure intensity until he had what the professionals still believe to be the eyelash curler against which all others should be measured. And while to the untrained eye it may look the same as a three quid version in Boots, they are apples and oranges. The Shu Uemuras don’t pinch or bend lashes in an unflattering right angle. They can be used both under and over mascara (this is always my preference – you get a better hold) without damage and even on short, pin-straight lashes like mine they give great and lasting curve. The mechanism is loose enough to allow partial release of tension, but can be tightened in case it becomes slack.

At time of writing, Shu Uemura’s eyelash curler has won a major beauty award for fifteen consecutive years and in all that time I don’t think I’ve met a single make-up artist who doesn’t own at least one set. The curler has appeared on magazine covers (Kylie Minogue’s iconic 1991 shoot for The Face), in films (The Devil Wears Prada, where it’s namechecked) and in pop videos (Annie Lennox’s wonderful ‘Why’ promo, featuring the extraordinary make-up skills of the great Martin Pretorius – a must-see for any beauty nerd), and been honoured with several limited editions, including a twenty-four-carat gold version. Shu Uemura’s eyelash curler is a beauty icon because, quite simply, it’s the best.

Bourjois Little Round Pots

There are few products more cheering than a little fat pot of Bourjois blush or eyeshadow, nor as instantly recognisable. None of us has lived in a time where these multicoloured pastel powders didn’t line high street chemist racks like freshly baked macarons in a patisserie window. These are domed, single shadows and blushers in sheer, muted tones including matriarch Cendre de Rose, an old Hollywood rouge, the deep, black-red hue of crushed rose petals, released in 1881, and Rose Thé, a dusky nude-pink blush born in 1936. For over 150 years, these traditional powders have provided the basis for the entire Bourjois brand, however cutting edge the rest of its offering has become.

The Fard Pastel powders – now known as Pastel Joues – are baked (much like Chanel’s European market shadows; for years, rumours abounded that they were made in the same factory) and so colour payoff is not as dramatic as with a modern, pressed pigment powder, but the finish is soft and blendable, and the colours are gentle, pretty washes that are hard to get wrong. Their rose scent is blissful, reminiscent of the dusty, flowery interior of a great-granny’s hanky drawer, and among my all-time favourite beauty smells.

The Little Round Pot franchise has been expanded over the years to include creme blushers that are among the very best at any price, and the packaging updated from rococo cherub design cardboard to chintzy floral tin, to gold-stamped coloured Bakelite (the packaging I grew up with), and the more convenient mirrored snap-compact we see today. But what has remained throughout is the chubby, tactile shape and moreish shade line-up that make Bourjois Little Round Pots the kind of rainy lunchtime purchase that can keep a girl going until clock-out.

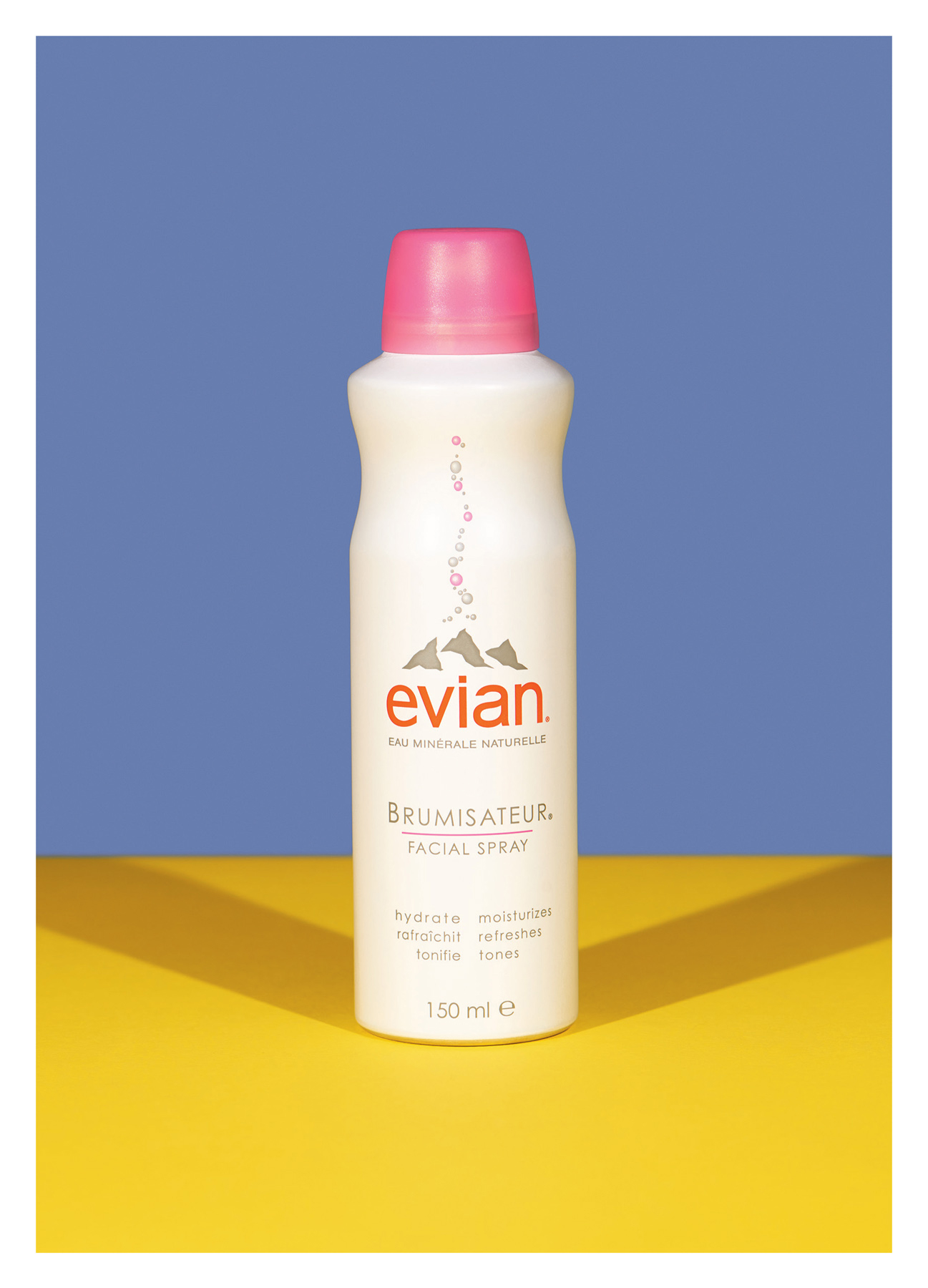

Evian Brumisateur

I must give props to Evian for somehow making a beauty icon of an almost laughably unnecessary product, but then the entire bottled water industry is based on turning a relatively free resource into a marketable commodity, so I guess popping water into an aerosol in the name of beauty was a fairly short leap for them to make. Yes, I am deeply cynical but yes, I am also no more immune to the hype than the next person. There was a time in my life when an Evian Brumisateur was all my heart desired. Magazines of the 1980s were always singing its praises, and if you were the kind of person who hoovered up every interview with make-up artists and beauty editors, you soon realised that this large can of water was in every industry kitbag.

Why? It’s a good question. The assertion by beauty professionals was that it ‘set’ make-up in place, though I’ve never personally found any evidence that this could be true, even over old-fashioned make-up formulas. It was also used to ‘freshen’ skin at the start of photo shoots, which is valid, if one has no access to a tap and an empty spray bottle, which admittedly were not as commonly available, and much less fine in the eighties (gardening sprays were more of a shower than a spritz). Where I can see the use for a Brumisateur is if you are working in some remote location, where cold water is scarce (the tin can tends to keep the water cooler), or if you are easily overheated – like in menopause – and you want something cooling and chemical-free in your handbag that won’t potentially cause any irritation.

In any case, Evian Brumisateur was successful in making itself a hugely desirable product, and in securing its place in every beauty junkie’s arsenal. I associate its packaging with the cluttered make-up table on countless photo shoots and filming sets and absolutely will concede that it launched an entire beauty category of facial spritzers, now a feature in most skincare brands with the addition of plant extracts, hyaluronic acid, glycerin and so on. I’ve also no doubt the dubious myth that a final spray of water locks make-up in place went on to inspire the development of true make-up fixing sprays like those by Urban Decay, MAC, NYX, Clarins and many others. But mostly I still see Evian’s original as little more than a status symbol born in an era obsessed with acquiring them. As with our obsession with buying wasteful plastic bottles of water in safe and plentiful supply from our own kitchen taps, I often think that future generations will look at Evian Brumisateur and wonder if ours had temporarily taken leave of its senses.

Benefit Benetint

Much like prawns, gin and bracelets, Benefit Benetint is something that looks so completely up my street, and yet, however persistently I try, I just can’t get onboard. My skin is too dry and too thirsty for this liquid rose-petal lip and cheek stain and so it sinks in well before I can blend it, and there it remains, like a clumsy Malbec spill on a white shag pile. On normals and oilies, Benetint is beautiful – but this isn’t the only reason I’m able to love it. Sometimes one quirky, interesting product can create enough mystique and ecstatic word of mouth, that it alone has the power to launch an empire – and never has that been more pleasingly demonstrated than here.

In 1977 an exotic dancer entered the tiny San Francisco beauty boutique of twins Jean and Jane Ford, and asked for something to stain her nipples (I do so enjoy hearing of a beauty gripe even I’d never considered), making them bright, perky and noticeable throughout a long show on a dark stage. The sisters took up the gauntlet and began experimenting in their kitchen, steaming real rose petals to create a deep, vivid red liquor to stain the skin. The liquid was poured in a tiny cork-stoppered glass bottle, hand-labelled with a naive line drawing of a single bloom, named ‘Rose Tint’ and delivered to the dancer. Needless to say, it was enthusiastically received, applied more widely than on the nips, and soon dozens of San Franciscan women wanted in.

Gradually, Benefit took off, arriving in the UK in the late nineties, where just a tiny handful of products were sold at Harrods. The press were captivated, the buzz about the by then repackaged and renamed Benetint in particular was huge. Now, Benefit is one of Britain’s top five bestselling colour brands. Some of their products are superb: they are particularly good at brows, bronzers and highlighters, but that original nipple tint remains its hero. When brushed onto the right skin and rubbed in with fingertips, it adds a pretty, effortless rose flush straight out of a Pre-Raphaelite watercolour that, sadly, I can only admire second-hand.

Mason Pearson Hairbrushes

I don’t know if you’ve ever sat in a hairdresser’s salon and witnessed your stylist find themselves temporarily unable to locate his or her Mason Pearson hairbrush, but I have on several occasions and can assure you it’s not pretty. Woe betide any chancer who attempted to make off with it. This is because a Mason Pearson rubber cushion brush remains, over 200 years after its original invention, the gold standard throughout the hairdressing world, with each owner feeling as attached to theirs as a chef to her favourite paring knife. I feel similarly about my own cherished brushes.

I encountered my first Mason Pearson at around six years old, when my aunt came to stay from London with a girlfriend who unpacked a large Mason Pearson and placed it ceremoniously on my tiny dressing table next to her Z-bed. Before then, I’d thought that hairbrushes were two quid jobs from the corner shop or chemist and associated them with tortuous and tear-filled detangling sessions in front of the fire – so fraught that my father once felt a yellow plastic handle, defeated by a knot as unyielding as a boulder, snap clean in half in my hair and sort of dangle, like Fay Wray in King Kong’s clutches. The Mason Pearson was different. Like the Mary Poppins of hairbrushes, it was firm, sturdy and no-nonsense but kind, modest and uncommonly elegant. Sadly, there was no way a family like ours could ever spend a week’s grocery money on a hairbrush, and so I had to wait until adulthood, when I was earning my own money and found myself in a traditional chemist in Mayfair ostensibly looking for Nurofen. That same 19-year-old ‘Handy’ sized Mason Pearson is still on my dressing table today, nobly doing its job, while an 8-year-old ‘Pocket’ size lives permanently in my handbag.

It’s endlessly satisfying to me that in an age of ceramic-barrelled, laser-cut, heated and rotating contraptions, this high-quality British-made icon prevails. Anyone who’s ever owned a Mason Pearson will know why. The weighty plastic handle (or a wooden one if you’re a purist – they’re still available on some models) feels smooth and solid in the hand, the bristles (natural bristle for fine hair, a bristle and nylon mix for normal hair, nylon bristles for thick and curly hair) glide through locks like a spoon through cream, gently massaging the scalp to dislodge dirt and distribute natural oils down the shaft, thus eliminating frizz. It backcombs brilliantly, neither scratches nor pulls, tames hair without causing static, and dries fringes or bangs better than anything (just pull the brush back and forth across your forehead while the dryer nozzle points downward). The Mason Pearson can also be used on children’s hair (I invariably buy the child’s size as christening gifts) without them wailing from bath to bedtime. The brush itself is extremely easy – and satisfying – to clean with a sturdy wide-toothed comb.