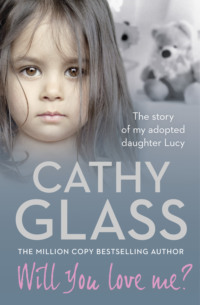

Will You Love Me?: The story of my adopted daughter Lucy

Leaving the tap running, Bonnie took off Lucy’s nappy and lifted her into the bath where she held her bottom under the tap. Lucy’s cries escalated. ‘Sssh,’ Bonnie said, as she washed her with an old flannel. ‘Please be quiet.’ But Lucy didn’t understand.

Having cleaned her back and bottom, Bonnie turned Lucy around and washed her front, finishing with her face and the little hair she had. Lucy gave a climactic scream and shivered as the water ran over her head and face. ‘Finished. All done!’ Bonnie said.

Turning off the tap, she lifted Lucy out of the bath and onto the towel. The comparative warmth and comfort of the fabric soothed Lucy and she finally stopped crying. ‘Good girl,’ Bonnie said, relieved.

She knelt on the floor in front of her daughter and patted her dry with the towel. Lucy’s gaze followed her mother’s movements apprehensively as though at any moment she might have reason to cry again. Once Lucy was dry, Bonnie wrapped the towel around her daughter like a shawl and then carried her into the half-light of the living room, where she sat on the threadbare sofa with Lucy on her lap. ‘Soon have you dressed,’ she said, kissing her head.

Bonnie took a disposable nappy from the packet she kept with most of her other possessions on the sofa. Bonnie owned very little; her and Lucy’s belongings were easily accommodated on the sofa and armchair. At least I won’t have much packing to do, she thought bitterly. Where she would go escaped her, but she knew she had no choice but to leave, now that Ivan’s money had gone.

Lying Lucy flat on the sofa, Bonnie secured the clean nappy with the sticky fasteners, and then reached to the end of the sofa for Lucy’s clean clothes. One advantage of working in the launderette was that she’d been able to wash and dry their clothes for free.

Taking the clean vest, Baby-gro and cardigan (bought second-hand), Bonnie dressed Lucy as quickly as she could. The only heating in the room was an electric fire, which was far too expensive to use, so Bonnie relied on the heat rising from the launderette to take the chill off the flat, but it was never warm. Lucy didn’t cry as Bonnie dressed her; in fact, she didn’t make any noise at all. Bonnie found that Lucy was either silent or crying; there was no contented in-between. Neither had she begun to make the babbling and chuntering noises most babies of her age do. The reason was lack of stimulation, but Bonnie didn’t know that.

Once Lucy was dressed, Bonnie replaced the sheet in the Moses basket ready for later and then carried her daughter into the squalid kitchen. Balancing Lucy on her hip with one arm, she filled and plugged in the kettle with the other, and then took the carton of milk from the windowsill. There was no fridge so the windowsill, draughty from the ill-fitting window, acted as a fridge in winter. Bonnie kept her ‘fridge foods’ there – milk, yoghurt and cheese spread. An ancient gas cooker stood against one wall but only the hobs had ever worked, so since coming to the flat five months previously Bonnie had lived on cold baked beans, cheese spread on bread, cornflakes, crisps and biscuits. Lucy was on cow’s milk – the formula was too expensive – and Bonnie wondered if this could be the reason for Lucy’s sickness and diarrhoea.

Bonnie prepared the milk for Lucy in the way she usually did, by half filling the feeding bottle with milk and topping it up with boiling water. Without a hob or milk pan it was all she could do, and it also made the milk go further. She made herself a mug of tea and, taking a handful of biscuits from the open packet, returned to the living room. She sat on the sofa and gave Lucy her bottle while she drank her tea and nervously ate the biscuits. She would have liked to make her escape now so she was well away from the area before Ivan returned in the morning and found his money and them gone, but the night was cold, so it made sense to stay in the flat for as long as possible. Bonnie decided that if she left at 6.00 a.m. she’d have two hours before Ivan arrived – enough time to safely make their getaway.

Physically exhausted and emotionally drained, Bonnie rested her head against the back of the grimy sofa and closed her eyes, as Lucy suckled on her bottle. She wondered if she should head north for Scotland where her mother lived, but her mother wouldn’t be pleased to see her. A single parent with a procession of live-in lovers, many of whom had tried to seduce Bonnie; she had her own problems. Bonnie had tolerated her mother’s lifestyle for as long as she could but had then left. Aged seventeen and carrying a single canvas holdall that contained all her belongings, Bonnie had been on the streets, sleeping rough or wherever she could find a bed. Bonnie’s two older brothers had left home before her and hadn’t kept in touch, so as Lucy finished the last of her bottle and fell asleep Bonnie concluded that she didn’t have anywhere to go – which was how she’d ended up at Ivan’s in the first place.

Dioralyte! Bonnie thought, her eyes shooting open. Wasn’t that the name of the medicine you gave babies and children when they had diarrhoea or sickness? Hadn’t she seen it advertised on television last year when she’d stayed in a squat where they’d had a television? She was sure it was. She had a bit of money – the tips from the day – she’d find a chemist when they opened in the morning and buy the Dioralyte that would make Lucy well again. With her spirits rising slightly, Bonnie looked down at her daughter sleeping peacefully in her arms and felt a surge of love and pity. Poor little sod, she thought, not for the first time. She deserved better than this, but Bonnie knew that better wasn’t an easy option when you were a homeless single mother.

Careful not to wake Lucy, Bonnie gently lifted her from her lap and into the Moses basket, where she tucked her in, making sure her little hands were under the blanket. The room was very cold now the machines below had stopped. It then occurred to her that tonight neither of them had to be cold – she didn’t have to worry about the heating bill as she wouldn’t be here to pay it. They could be warm on their last night in Ivan’s disgusting flat! Crossing to the electric fire she dragged it into the centre of the room, close enough for them to feel its warmth, but not too close that it could burn or singe their clothes. She plugged it in and the two bars soon glowed red. Presently the room was warm and Bonnie began to yawn and then close her eyes. She lifted up her legs onto the sofa, kicked off the packet of nappies to make space and then curled into a foetal position on her side, resting her head on the pile of clothes, and fell asleep.

She came to with a start. Lucy was crying, and through the ill-fitting ragged curtains Bonnie could see the sky was beginning to lighten. ‘Shit!’ she said out loud, sitting bolt upright. ‘What time is it?’ Groping in her bag she took out her phone. Jesus! It was 7.00 a.m. The heat of the room must have lulled her into a deep sleep; Ivan would be here in an hour, possibly sooner!

With her heart racing and leaving Lucy crying in the Moses basket, Bonnie grabbed the empty feeding bottle from where she’d left it on the floor and tore through to the kitchen. She filled the kettle and then rinsed out the bottle under the ‘hot’ water tap. While the kettle boiled she returned to the living room and, ignoring Lucy’s cries, changed her nappy. It was badly soiled again; she would find a chemist as soon as she could. Returning Lucy to the Moses basket, Bonnie flew into the kitchen, poured the last of the milk into Lucy’s bottle and topped it up with boiling water. Back in the living room she put the teat into Lucy’s mouth and then propped the bottle against the side of the basket so Lucy could feed while she packed.

Opening the canvas bag, Bonnie began stuffing in their clothes and then the nappies and towel. She put on her hoody and zipped it up; she didn’t own a coat or warmer jacket. Bonnie then ran into the bathroom, quickly used the toilet, washed her hands in the lukewarm water and, taking her toothbrush and the roll of toilet paper, returned to the living room and stuffed those into the holdall. Bonnie didn’t have any toiletries or cosmetics; they were too expensive and she never risked stealing non-essential items; she could live without soap and make-up.

In the kitchen Bonnie collected together the little food she had left – half a packet of biscuits, two yoghurts and a tub of cheese spread. She remembered to take a teaspoon from the drawer so she could eat the yoghurts, and then returning to the living room she put them all in the holdall. The bag was full now so she zipped it shut. She’d packed most of their belongings; all that remained were Lucy’s soiled clothes and they would have to stay. There wasn’t room for them and they would smell.

Bonnie checked the time again. It was now 7.15. Her heart quickened. She’d have to be careful as she left the area and keep a watchful lookout for Ivan. He arrived by car each morning, but from which direction she didn’t know. With a final glance around the dismal living room and with mixed feelings about leaving – at least the place had provided a roof over their heads and a wage – Bonnie threw her bag over her shoulder and then picked up the Moses basket. She felt a stab of pain in her back from where Vince had pushed her into the washing machine.

Opening the door that led from the flat to the staircase, Bonnie switched on the timed light and then manoeuvred the Moses basket out and closed the door behind her. She began carefully down the stairs, her stomach cramping with fear. The only way out was through the launderette and if for any reason Ivan arrived early, as he had done a couple of times before, there’d be no escape. The back door was boarded shut to keep the yobs out. Halfway down the stairs the light went out and Bonnie gingerly made her way down the last few steps, tightly clutching the Moses basket and steadying herself on the wall with her elbow. At the foot of the stairs she pressed the light switch and saw the door to the launderette. Opening it, she went through and then closed it behind her. With none of the machines working the shop was eerily still and cold. She began across the shop with her eyes trained on the door to the street looking for any sign of Ivan; her heart beat wildly in her chest. With one final glance through the shop window, she opened the door. The bell clanged and, leaving the sign showing ‘Closed’, she let herself out.

Chapter Three

Concerned

The cruel northeasterly wind bit through Bonnie’s jeans and zip-up top as she headed for town, about a mile away. She had no clear plan of what she should do, but she knew enough about being on the streets and sleeping rough to know there would be a McDonald’s in the high street open from 6.00 a.m.; some even stayed open all night. It would be warm in there and as long as you bought something to eat or drink – it didn’t matter how small – and sat unobtrusively in a corner, the staff usually let you stay there indefinitely. That was how she’d met Jameel last year, she remembered, sitting in a McDonald’s. He’d sat at the next table and had begun talking. When he’d found out she was sleeping rough, he’d taken her back to the squat he shared with eight others – men and women in their late teens and early twenties, many of whom had been in the care system. One of the girls had had a four-year-old child with her, and at the time Bonnie had thought it was wrong that the kid should be forced to live like that and felt it would have been better off in foster care or being adopted, but now she had a baby of her own it was different; she’d do anything to keep her child. Bonnie had lived at the squat for two months and had only left when Vince had reappeared in her life. Bad move, Bonnie thought resentfully, as she continued towards the town with Lucy awake and gazing up at her.

‘You all right, love?’ a male voice boomed suddenly from somewhere close by.

Bonnie started, stopped walking and turned to look. A police car had drawn into the kerb and the male officer in the driver’s seat was looking at her through his lowered window, waiting for a reply.

‘Yes, I’m fine,’ she said, immediately uneasy.

‘Bit early to be out with a little one in this cold,’ he said, glancing at the Moses basket she held in front of her.

Bonnie felt a familiar stab of anxiety at being stopped by the police. ‘I’m going on holiday,’ she said, trying to keep her voice even and raising a small smile. She could see from his expression that he doubted this, which was understandable. It was the middle of winter and she didn’t exactly look like a jet-setter off to seek the sun. ‘To my aunt’s,’ she added. ‘Just for a short break while my husband’s away.’

The lie was so ludicrous that Bonnie was sure he’d know. Through the open window she could see the trousered legs of a WPC sitting in the passenger seat.

‘Where does your aunt live?’ the officer driving asked.

‘On the other side of town,’ Bonnie said without hesitation. ‘Not too far.’

The WPC ducked her head down so she, too, could see Bonnie through the driver’s window. ‘How old is the baby?’ she asked.

‘Six months,’ Bonnie said.

‘And she’s yours?’

‘Yes. Don’t worry, she won’t be out in the cold long. I’ll get a bus as soon as one comes along.’

Bonnie saw the driver’s hand go to the ignition keys. This was a bad sign. She knew from experience that if he switched off the engine it meant they would ask her more questions and possibly run a check through the car’s computer. When that had happened before she hadn’t had Lucy, so she’d legged it and run like hell. But that wasn’t an option now. It would be impossible to outrun the police with the holdall and Lucy in the Moses basket.

‘Where does your aunt live?’ the WPC asked, as the driver cut the engine.

Shit! Bonnie thought. ‘On the Birdwater Estate,’ she said. She didn’t know anyone on the estate, only that it existed from seeing the name in the destination window on the front of buses.

Suddenly their attention was diverted to the car’s radio. A message was coming through: ‘Immediate support requested for an RTA’ – a multi-vehicle accident on the motorway. Bonnie watched with relief as the driver’s hand returned to the ignition key and he started the engine.

‘As long as you’re OK then,’ the WPC said, straightening in her seat and moving out of Bonnie’s line of vision.

‘I am,’ Bonnie said. ‘Thank you for asking.’

The driver raised his window and the car sped away with its lights flashing and siren wailing.

‘That was close,’ Bonnie said, and quickened her pace.

She knew she’d attract the attention of any police officer with child protection on his mind, being on the streets so early with her holdall and a baby. That was how she’d arrived at Ivan’s launderette at 7.30 a.m. when Lucy had been one month old. Living rough, she’d dodged a police car that had been circling the area, and Bonnie had run into the launderette, which had just opened, to find Ivan cursing and swearing that the woman who should have been opening up and working for him had buggered off the day before. They’d started talking and when she’d heard that the job came with the flat above she’d said straight away she would work for him.

Now she crossed the road and waited at the bus stop. It was only a couple of stops into town, and she could just afford the fare. She also knew from experience that she was less likely to be stopped by the police while waiting at a bus stop than she was while walking.

It was a little after 8.00 a.m. when Bonnie entered the brightly lit fast-food restaurant, with its usual breakfast clientele. She was thirsty, her arms and back ached from carrying the Moses basket and bag and she desperately needed a wee. She was also hungry; apart from the handful of biscuits she’d eaten the evening before, she’d had nothing since lunch yesterday, and that had only been a cheese-spread sandwich made from the last of the bread. Although she had enough money to buy breakfast, she had no idea how long she’d be living rough, so she wasn’t about to spend it until it became absolutely necessary. Bonnie opened the door to the corridor that led to the toilets and one of the staff came out. ‘Oh, a baby!’ she said, surprised, and then continued into the restaurant to clear tables.

Bonnie manoeuvred the Moses basket and holdall into the ladies. Fortunately it was empty, so she left the bag and Moses basket with Lucy in it outside the cubicle with the door open while she had a wee. Flushing the toilet, she came out, washed her hands and then held them under the hot-air dryer. As the dryer roared, Lucy started and cried. ‘It’s all right,’ Bonnie soothed, and quickly moved away from the dryer.

She picked up the Moses basket and bag, and as she did she caught sight of her face in the mirror on the wall. Under the bright light she looked even paler than usual and she seemed to have lost weight; her cheekbones jutted out and there were dark circles under her eyes. With a stab of horror, Bonnie thought that if she didn’t change her lifestyle soon she’d end up looking like her mother, haggard from years of drinking and smoking and being knocked around.

Returning to the restaurant, Bonnie ordered a hot chocolate for herself and a carton of milk for Lucy. ‘Eat here or takeaway?’ the assistant asked.

‘Here,’ Bonnie confirmed.

She paid and then, lodging the drinks upright at the foot of the Moses basket so she could carry everything in one go, she crossed to one of the long bench seats on the far side – away from the cashiers and the draughty door. Placing the Moses basket on the seat beside her, Bonnie quickly began drinking her hot chocolate. The warmth and sweetness was comforting and reminiscent of the hot milky drinks her gran used to make for her when she’d stayed with her as a child. Bonnie wondered what her gran was doing now. Her mother had fallen out with her and they hadn’t spoken for some years. Bonnie loved her gran, although she hadn’t seen her since she’d left home eight years previously.

She took the packet containing the last few biscuits from her bag and kept it on her lap, out of sight of the staff, as she quickly ate them. The sugar rush lifted her spirits and helped quell her appetite for the time being. Lucy was watching her, but didn’t appear to be hungry so Bonnie decided she’d keep the carton of milk she’d just bought for later and tucked it back in at the foot of the Moses basket, ready for when it was needed. She also had the yoghurts, one of which she’d give to Lucy later. She’d started giving her some soft food – yoghurt, a chip chewed by her first to soften it or a piece of bread soaked in her tea. When they were settled, she thought, and she had more money, she’d start buying the proper baby foods for weaning.

‘It won’t always be like this,’ Bonnie said out loud, turning to her daughter and gently stroking her cheek. ‘It will get better. I promise you.’ Although how and when it would get better Bonnie had no idea.

At 9.00 a.m. Bonnie hitched the bag over her shoulders, picked up the Moses basket and left the fast-food restaurant in search of a chemist. Lucy was asleep now and, although she hadn’t been sick or had a dirty nappy yet that morning, Bonnie wanted to buy the medicine so she had it ready in case it was needed. She tried to be a good mum, she told herself, but it was very difficult with no home, no regular income and having her own mother as a role model. When she’d been a child she’d assumed that the chaos and poverty she and her brothers were forced to live in was normal, that all families lived like that. But when she was old enough to play in other children’s houses she realized not only that it was not normal but that others on the estate pitied her and criticized her mother for neglecting her and her brothers. Bonnie wondered why no one had intervened; perhaps it was because of her mother’s ugly temper, which she’d been on the receiving end of many times and was always worse when she’d been drinking. This might also have been the reason why the social services hadn’t rescued her and her brothers as they had some of the other kids on the estate, she thought; that, or they weren’t worth saving – a view she still held today.

Bonnie spotted the blue-and-white cross on the chemist’s shop a little further up and went in. There were two customers already inside: a lady browsing the shelves and a man being served at the counter. Bonnie scanned the shelves looking for the medicine she needed but couldn’t find it. Once the man at the counter had finished, she went up to the pharmacist – a rather stern middle-aged Asian woman dressed in a colourful sari.

‘I think what I need is called Dioralyte,’ Bonnie said.

‘Is it for you?’ the pharmacist asked, giving Bonnie the once over.

‘No, for my baby.’

‘How old is it?’

‘Six months.’

She glanced at the Moses basket Bonnie held in front of her. ‘What are the symptoms?’

‘Sickness and diarrhoea.’

‘How long has she been ill?’

‘Two days,’ Bonnie said.

‘She needs to see a doctor if it continues,’ the pharmacist said. Reaching up to a shelf on her right, she took down a box marked Dioralyte. ‘This box contains six sachets,’ she said, leaning over the counter and tapping the box with her finger. ‘You follow the instructions. Mix one sachet with water or milk. You understand this doesn’t cure sickness and diarrhoea? It replaces the salts and glucose lost from the body. If your baby is no better in twenty-four hours, you must take her to your doctor.’

‘I will,’ Bonnie said, taking her purse from her pocket.

‘Four pounds twenty,’ the woman said.

‘That’s a lot!’ Bonnie exclaimed. ‘Can’t I just buy two sachets?’

The pharmacist paused from ringing up the item on the till and looked at Bonnie. Bonnie knew she should have kept quiet and paid. Through the dispensing hatch Bonnie could see a man, presumably the woman’s husband, stop what he was doing and look at her. Then the woman came out from behind the counter and leaned over the Moses basket for a closer look at Lucy.

‘I can smell sick,’ she said, feeling Lucy’s forehead to see if she had a temperature. Lucy stirred but didn’t wake.

‘It might be on the blanket,’ Bonnie said defensively. ‘I didn’t have time to wash that before I left. Her clothes are clean.’

‘Have you taken the baby’s temperature?’ the woman now asked.

‘Yes,’ Bonnie lied. ‘She doesn’t feel hot, does she?’

‘No, but that isn’t necessarily a good test. What was her temperature?’

‘Normal,’ Bonnie said, with no idea what that was.

The woman looked at her and then returned to behind the counter. ‘Babies can become seriously ill very quickly,’ she said. ‘You need to watch her carefully. If you go to your doctor’s, they will give you a prescription for free. Where do you live?’

‘Eighty-six Hillside Gardens,’ Bonnie said, giving the address of the launderette she’d just left. It was the only local address she knew by heart.

‘Do you want the Dioralyte?’

‘Yes,’ Bonnie said, and quickly handed her a five pound note.

‘Remember, you see your doctor if she’s no better tomorrow,’ the woman said again, and gave her the change.

‘I will,’ Bonnie said, just wanting to get out. Once she’d tucked the change into her purse, she dropped it along with the paper bag containing the Dioralyte into the Moses basket and hurried from the shop.

However, inside the shop Mrs Patel was concerned. The young woman she had just served looked thin and gaunt and her baby was ill. She’d appeared agitated and the basket she carried her baby in was old and grubby; she hadn’t seen one like it for years. And why was the mother out on the streets with her bags packed in the middle of winter when her baby was ill? It didn’t add up; something wasn’t right. Mrs Patel was aware that in the past chemists had missed warning signs when intervention could have stopped suffering and even saved a life. Half an hour later, having voiced her concerns to her husband, he served in the shop while she went into their office at the back of the shop and phoned the social services.