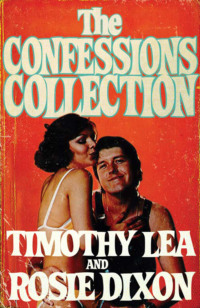

The Confessions Collection

“Look, Sid,” I say, my mind returning to the window cleaning, “couldn’t you just give me a trial? A couple of weeks maybe. I’m certain I could do the job. If I can’t, well, O.K. then.”

Sid is exploring the darkness and doesn’t seem to be listening to me. Eventually he sees what he’s looking for and, beckoning to me to follow him, makes towards the pond. By the water’s edge a fat old git is buttoning his oilskin trench coat and spitting words at a thin bird who is picking pieces of grass off her skirt. No prizes for guessing what they’ve been up to. The man bends down and reels in his line which, I notice, only has a weight on the end of it – no hooks. Presumably his technique is to whirl the weight round and round above his head and bash the fish over the bonce with it.

“Hallo, Lil” says Sid all cheerful like, “You busy?”

“With old kinky-coat” says the bird, “You must be joking. He exhausted himself screwing his rod together.”

The fat man says something ‘not nice’, as my mother would say, and collapsing his collapsible stool, hurries away.

“Lil,” says Sid, “I’d like you to meet my brother-in-law, Timmy. Timmy this is my aunty Lil.”

“Not so much of the aunty, ta.” says Lil. “Pleased to meet you Timmy. I don’t remember you at the wedding.”

“Timmy was detained elsewhere. He was giving her majesty pleasure.”

Sid’s aunty! What a turn up. She doesn’t seem old enough.

She’s not bad looking really. A bit tired and a bit skinny but not bad. Fancy her being on the game.

“She’s my mum’s youngest sister. Much younger.”

“Pleased to meet you,” I say. I have a nasty feeling that Sid has engineered our meeting with what the B.B.C. calls an ulterior motive in view. Sid immediately proves me right. Waiting no longer than the space of time it takes fatso to merge into the background he begins to speak.

“Lil,” he says, “with my friend Timmy, actions speak a bloody sight louder than words, or so he would have me believe. He’s not much of a chatterbox but he’s shit hot when it comes to the proof of the pudding. I’d like you to take him in hand or anything else you have to offer and give me your views.”

I start to say something but Sid shuts me up and sweeps Lil away into outer darkness. I hear them rabbiting away and then Lil nips back again all peaches and cream. Before I can say anything she’s kneading the front of my trousers like dough and steering me towards the wide open spaces.

“Hey, Sid—” I begin but there’s no stopping her.

“Don’t be frightened,” she murmurs, “Lil’s going to take care of you.”

The minute she opens her mouth with that quiet reassuring tone I can feel my old man disappearing like a pat of butter at the bottom of a hot frying pan. It’s about as sincere as Ted Heath singing the Red Flag. At the same time I realise that Sid is setting this up so he can see what I’m made of, and that after the last cock-up I can’t afford to blow it.

It’s in this uneasy frame of mind that I find myself wedged up against a tree with the lights of Clapham sparkling all around me and Aunty Lil’s hand pulling the zip of my fly out of its mooring.

“Ooh, ooh, ooh,” she grunts fumbling away, but my cock has got about as much sensation in it as a headline in ‘Chicks Own’.

“Come on, darling,” she pants, “don’t you want a nice time?”

“I feel we’re being watched” I say and it’s no exaggeration. Talk about Edward G. Robinson in ‘The Night Has A Thousand Eyes’. There’s a crackle of plastic macs around us like a crisp eating contest. That’s another thing I’ve got against Clapham Common. The public don’t only come to watch the football matches.

“Don’t worry about them,” says Aunty Lil soothingly, “they’re only jealous.”

Nothing is happening down below and I can see she’s getting a bit fed up. What with the beer and the tension I’m under, and all those dirty old buggers creeping round us like red indians, I don’t think it’s going to be one of my nights. Lil stops mauling me and puts her hands on my shoulders.

“Don’t worry about the money,” she says, “it’s on the family.”

I try and blurt out my thanks and in a desperate effort to get in the mood I attempt to kiss her. This is definitely not a good move, for she twists away as if I’ve sunk fangs into her neck.

“Don’t do that!” she snarls, “Don’t ever do that.”

It’s obvious that I’ve seriously offended her and I’ve since learned that a lot of whores don’t mind what you do to them below the waist but they reserve their mouths for their boyfriends – or girl friends since quite a few of them are bent. There is also the problem of smudged make-up and Clapham Common isn’t exactly crawling with powder rooms.

“I’m sorry,” I mutter.

“Get on with it,” she spits. I can see she’s had enough. I’m all for chucking it in but I think of Sid and some kind of pride drives me on.

“Come on, come on.”

I put my hands underneath her skirt and she sucks in her breath because they must be quite cold. She’s not wearing any knicks which is no surprise and I fumble till I find something like a warm pan scourer, Lil’s arms are round me and I’m gritting my teeth and staring over her shoulder towards the string of lights that run across the common. There’s a bit of something going for me down below now, so I grab hold of it and lunge forward until I feel myself secured between her legs. It’s really very disappointing after all I’ve read and heard about it, but at least I’m there. I put my hands behind her arse and start pulling her towards me. Sid should be quite impressed.

“Well,” says Lil, “aren’t you going to put it in?”

“I have put it in!” I gulp.

“You stupid berk. You’ve got it caught under my suspender strap.”

CHAPTER TWO

We return home in silence. At least I’m silent. Sid keeps pissing himself with laughter and has to be left behind to recover. I can hear him wheezing: “her suspender strap, oh my God,” and terrifying people out of their wits. I feel like belting him but I know it won’t do any good and frankly I’m a bit frightened of him anyway.

We live in a semi off Nightingale Lane which is the class street round these parts. In fact Scraggs Road is quite a long way off but my old mum always mentions the two in the same beery breath and the habit has rubbed off on me. Mum is very sensitive about her surroundings and I’ve heard her tell people we live at Wandsworth Common because she thinks it sounds better. I reckon its Balham myself but mum doesn’t want to know about that. She has a photograph of Winston Churchill in the outside toilet so you can see where her sympathies lie. It’s pretty damp out there and poor old Winnie is getting mildew, but when mum gets in there its like Woburn Abbey as far as she’s concerned.

When we lumber into the front room the family are grouped in their usual position of homage to the telly. Dad is dribbling down his collar stud and his hands are thrust protectively down the front of his trousers as if he reckons someone was going to knock off his balls the minute his eyes are closed. As he gets older he gets more and more embarrassing does dad. He must be the world champ at pocket billiards. Mum is sitting there guzzling down ‘After Eights’ and smoking at the same time so the ashtrays are full of fag ends and sticky brown paper spilling onto the floor. Rosie’s position has hardly changed since we went out except that her mouth has dropped open a bit as if her jaw has started melting. Her fingers are still clicking away seemingly independent of the rest of her body. Looking at her I have to confess that our Rosie is going to seed fast.

They are all watching ‘Come Dancing’ and every few seconds the birds make little exclamations of wonder and surprise as another six hundred feet of tuile and sequins hover into sight or Peter West cocks the score up. Dad’s head has lolled back and from the noise he is making it sounds as if his dentures are lodged in his throat.

“Did you have a nice time?” says Mum without taking her eyes off the set. She’d say that to you if you had just come back from World War Three.

“Alright” I say quickly before Sid can get his oar in. “We had a couple of jars at the Highwayman.”

Its amazing but on the mention of the pub Dad’s eyes leap open as if a little alarm bell has rung in his mind.

“Did you bring us back a drop of something?” he says.

“Sorry Dad” says Sid, “we moved out a bit sharpish and it quite slipped my mind.”

“Leave him alone Dad” says Rosie. “That’s a nice little dress isn’t it mum. Eh, Sid, how would you fancy me in that?”

“You’d look bloody nice on top of a Christmas tree” says Sid.

“It’s no good asking him,” goes on Dad, “he can’t even afford a bottle of brown ale for his father-in-law. You won’t get any dresses out of him.”

“I told you, to leave him alone Dad. Sid is saving up for the down payment on one of those new flats up by the common. He hasn’t got the money to keep you in booze.”

“I don’t want champagne and caviar. I just ask to be remembered, that’s all. A bit of common civility – that’s all I ask for. Bugger me, he isn’t bankrupting himself, the rent he’s paying to stay here.”

“Give over, Dad” says Mum. “You’ve already said all that. You know Sid is doing his best.”

“That’s what he tells me” says Dad, who is probably the most boring old git in the world when he puts his mind to it. “I haven’t seen any evidence of it – not even a single solitary bottle of brown ale.”

“Oh, for Chrissakes,” explodes Sid, “I can’t stand any more of this. I’m going to bed. Look, here’s some money. Go and buy your own bloody brown ale.” And he chucks two bob down at dad’s feet and slams out. Immediately everybody starts shouting and it’s all turning into another typical evening at the Lea’s. Rosie throws a tizzie and has to be comforted by Mum and they both turn on Dad while Peter West tells us it all depends on the result of the formation dancing. Dad is in a spot because you can see he wants to pocket the two bob but knows that if he does the women will really start riding him. He solves that one by picking the money up and resting it casually on the arm of his chair as if he was frightened that someone might trip over it. Rosie is ranting about how they both might as well get out because Dad has never liked Sid and Mum is trying to quieten her down, saying things like “ssh, think about the neighbours”.

She’s very neighbour-conscious is Mum. It nearly broke her heart when Mr Ngobla moved in next door with the five little Ngoblas. She’s dead keen that nothing untoward should take place which might make the Ngoblas suspect that they aren’t a great deal less refined than we are. “Is that really his wife?” Mum keeps saying. “I’d never have recognised her. They all look the same to me. No, of course I didn’t mean to give offence. I thought it was one of his – you know – one of his other ones.”

Dad is much more tolerant than Mum. He’s always leaning over the wall and explaining to them that many of our ways must strike them as being a bit strange and that a few years ago we had some pretty primitive customs ourselves. You can see them looking at each other when he’s talking.

Anyway, that’s nothing to do with this evening’s caper which ends with Central London winning by one point and Mum going off to make a cup of Ovaltine. Dad, choosing his moment well, pockets the two bob and shuffles off to bed. Rosie is still snivelling and showing no interest in professional wrestling from the Winter Gardens, Morecambe, which shows how serious things are. I turn the set off and for a few minutes we have to get used to the strange sound of our voices unaccompanied by the background noise of the telly.

“I should have married Rory,” sniffs Rosie, “that would have made Dad happy.”

Rory was a big silent slob who worked in a garage and used to leave greasemarks all over the settee. He and Rosie were very close for a while and it was a union Dad would have smiled upon since Rory’s old man owned the garage. They even went on holiday once. Rory and Rosie I mean, not his old man. A few months after that Rosie faints down at the palais and tongues start wagging backwards and forwards like wedding bells. They’ve got it a bit wrong though, for it’s about that time that Sid rolls up and Rosie falls like a pair of lead knickers. She nips off to see a friend of a friend one evening and comes back looking pale but relieved. A couple of weeks later they’re calling the banns. Rory is very cut up about it and saying how he’s going to smash Sid’s face in, but he never does anything. How much Sid knows about it all I’ve never found out.

“I saw Rory the other day,” I say. “He was asking after you.”

Now this is a complete lie and I don’t know why I say it but I just have the feeling that I might be doing myself a bit of good. Rosie looks really agitated.

“What did he say?”

“Said how about having a drink.”

“What me?”

“No, no. Me.”

“And what did you say?”

“I said fine.”

“Did he say anything else?”

I’m thinking very fast now. Rosie is obviously dead worried that Rory is going to start blabbing his mouth off. She also has a lot of influence over Sid. More than he’d care to let on. This might be what I’m looking for.

“Oh, he started saying there were a few things he’d like to tell Sid. He was a bit pissed, you couldn’t take him seriously.”

“I don’t want him near Sid.”

“You’ve nothing to worry about. He didn’t say he was going to glass him or anything.”

“No, well I still think its better that they don’t meet. Let bygones be bygones.”

“Yes, you’re probably right. Trouble is, Rory was talking about a job up at the garage and you know what Dad’s been like lately. I was thinking of taking it.”

It’s a fact that Dad has had the dead needle with me ever since I got back from Bentworth, and I usually get more of it than Sid. This evening’s little interchange has not been typical.

The reference to the job with Rory is obviously a master-stroke and I can see Rosie wriggling.

“It’s a bit difficult isn’t it,” I go on, “I mean, I’ve got to get a job and the garage seems favourite but I can understand your feelings about Rory. It would be difficult to stop him coming round here.”

“I haven’t got any feelings about Rory” she snaps, “I just don’t want him telling Sid a lot of lies about me.”

‘No, of course not.” I shake my head understandingly and then my face lights up as an idea suddenly comes to me. “I’ve just thought,” I say, “Sid was telling me that the old window cleaning lark was picking up a treat. Perhaps I could go in with him? Keep it in the family and all that. I’ve heard him saying he’s got more work than he can handle.”

I’m holding my breath and crossing my fingers and, by Christ, it works.

“That’s a good idea,” she says. “Why don’t you have a word with him about it?”

“I would but – you know – it’s his business, and what with him living here and me being family, I don’t want him to feel that I’m pushing it too much. You know what I mean? I think it would be much better if you could mention it to him first. Might make things easier with Dad too.” I soon learn that I’m overplaying my hand there.

“Dad can get stuffed,” she says, “he’s always had it in for Sid and now he’s beginning to do alright for himself he’s getting jealous.” He’s not the only one I think.

“Yes, you’re probably right. Well, if you could have a word with Sid and see if there’s anything going, I’d be very grateful, Rosie. I’m supposed to be seeing Rory tomorrow and he was pushing me for an answer so maybe I can say ‘no go’ and warn him off, so to speak.”

“I’ll talk to him tonight,” says Rosie firmly, “it seems a good idea to me, really it does. And if you can, see Rory doesn’t make any fuss – of course he can’t do anything but you know what it’s like.”

“Of course, Rosie, don’t worry yourself. I’ll see you alright. It’ll be a sort of tit for tat won’t it?”

She looks at me a bit hard but I give her my brotherly smile and I don’t think she suspects anything.

A few minutes later she goes to bed and I have my Ovaltine with Mum. It makes me think how I could have used all that malt, milk and eggs and added vitamins earlier in the evening. I can never understand how the stuff is supposed to give you more energy than you know what to do with and yet help you to sleep at the same time. Mum pushes off and I take a quick shufty in the hall stand where Dad keeps all the dirty books he’s ashamed to bring into the house. Things must be bad down at the lost property office where he works because there’s not so much as a censored copy of ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’ let alone the hard core porn he thrives on. Dad and his mates down at the L.P.O. are on to a good thing because, knowing that no one is ever going to come round and confess to having lost a fully illustrated copy of ‘Spanking through the ages’ they nick everything juicy they can lay their hands on.

My room is at the top of the house; in fact if it was any higher my head would be sticking out of the chimney, and I have to go past Sid and Rosie’s room to get there. Normally, at this time, I would be treated to the sound of creaking springs, but tonight I can hear Rosie rabbiting away and Sid making occasional muffled grunts that sound as if he’s got a pillow over his head. I hope she is getting stuck in on my behalf.

I lie in my bed, naked, and listen to somebody’s wireless playing a few houses away. Or maybe they’re having a party. Now that I don’t need it I’ve got a bloody great hard on and when I think of Silk Blouse, or even Aunty Lil, or any of the millions of birds who must be lying alone in bed and feeling like a bit of the other, I’m bloody near bursting into tears.

When I come down the next morning Sid is sitting there with his hands wrapped round a cup of tea and he’s giving me an old fashioned expression that tells me Rosie has been getting at him.

“Morning” I say agreeably. Sid doesn’t answer.

“You going down the Labour today?” says Mum.

“I went yesterday” I say. “I don’t want to look as if I’m begging.”

“Well, don’t leave it too long, dear, you know what your father is like.”

I help myself to a cup of tea and ask Sid for the sugar. He slides it across very slowly without taking his hand off the bowl. I think Paul Newman did it in ‘Hud’ but I can’t be certain.

“I had a talk with your sister last night,” he says.

“Oh, really.”

“Yes, I thought you’d be surprised.”

“Well, I didn’t know you talked to each other as well.”

“Don’t be cheeky” says Mum.

“Don’t suppose you’ve any idea what we were talking about?” says Sid.

“No.”

“No?”

“No.”

“Well it was about what we were talking about yesterday.”

“Really? Oh, interesting.”

“Yeah. And to stop us poodling on like this any longer I might as well tell you that I’ve agreed to give it a go.”

“Great!” I say. “Ta very much. You won’t regret it.”

“Um, we’ll see.”

“What you on about?” says Mum.

“Sid and I are going into business” I say. “I’m going to be a window cleaner, Mum.”

“That’s nice, dear. Do you think he’ll be alright, Sid?”

“No” says Sid bitterly, “but you don’t expect much from a brother-in-law do you?”

“Now Sid,” says Mum, all reproachful, “that’s not very nice. That’s not the right spirit to work together in.”

“It’s alright, Mum,” I say, “he’s only joking, aren’t you, Sid?” Sid can’t bring himself to say ‘yes’ but he nods slowly.

“Today, you can do your Mum’s windows” he says, “It’ll be good practice for you. Tomorrow we’ll be out on the road.” He makes it sound like we’re driving ten thousand head of prime beef down to Texas.

“That’s a good idea” says Mum, “I was wondering when someone was going to get round to my windows.”

Sid gives me a quick demo and it looks dead simple. There’s a squeegee, or a bit of rubber on a handle, that you sweep backwards and forwards over a wet window and that seems to do the trick in no time. With that you use the classical chamois and finish off with a piece of rough cotton cloth that won’t fluff up called a scrim. It seems like money for old rope and I can’t wait to get down to it. Sid pushes off to keep his customers satisfied and I attack Mum’s windows. Attack is the right word. In no time at all I’ve put my arm through one of them and I’m soaked from head to foot. The squeegee is a sight more difficult to use than it looks. Whatever I do I end up with dirty lines going either up or down the window and it gets very de-chuffing rearranging them like some bloody kid’s toy. When I get inside it’s even worse because the whole of the outside of the windows look as if I’ve been trying to grow hair on them. That’s what comes of wearing the woolly cardigan Rosie knitted for me last Christmas. I get out and give the windows a shave and then I find that there are bits that are still dirty which you can only see from the inside. I’m popping in and out like a bleeding cuckoo in a clock that’s stuck at midnight. Inside at last and I drop my dirty chamois in the goldfish tank and stand on Mum’s favourite ashtray which she brought back the year they went to the Costa Brava. By the time I’ve cleaned up and replaced the broken window-pane – twice – it’s dinner time and I’m dead knackered.

Sid drops in to see how I’m getting on and you can tell that he’s not very impressed.

“At this rate,” he says, “you might do three a day – with overtime.”

“Don’t worry,” I say. “It’s a knack. It’ll come.”

Sid shakes his head. “What with that and your lousy sense of direction” he says. “I’ll be surprised if you last the first day.”

But he’s wrong. It doesn’t go badly at all. Sid starts me off at the end of a street and gives me a few addresses and though I’m dead nervous, I soon begin to get the hang of it. I drop my scrim down the basement a couple of times but there are no major cock-ups and nobody says anything. A few of them ask where Sid is but on the whole it’s all very quiet. In fact, if I wasn’t so busy trying to concentrate on the job I’d be a bit choked. After what Sid has led me to believe, these dead-eyed old bags look about as sexed up as Mum’s Tom after he had his operation. Curlers, hairnets, turbans, carpet slippers, housecoats like puke-stained eiderdowns – I was expecting Gina Lollamathingymebobs to pull me on to her dumplings the minute I pressed the front door bell. Perhaps Sid was having me on or perhaps, and this is much more likely, its some crafty scheme to con me into the business for next to nothing. Sid hasn’t been over-talkative about the money side of the deal. I do get one spot of tea but the cup has a tide-mark on it like a coal miner’s bath and I reckon the slag that gives it to me has the same. Perhaps Sid has purposely given me a list of no-hopers after my performance, or lack of it, with Aunt Lil.

This is a subject I tax him with when we’re having a pint and a wad in the boozer at lunch time but he is quick to deny it.

“Oh no,” he says, “I wouldn’t do a thing like that. No, it’s the school holidays, you see. That always calms them down a bit. You wait till the little bleeders go back – then you’ll be amongst it.”

I had to admit that a lot of kids have been hanging around asking stupid questions and generally getting in the way, so perhaps he’s on the level.

“Don’t worry,” he goes on, “I’ve got a little treat lined up for this afternoon. Very good friend of mine, she’ll see you alright.”

“Not Aunt Lil?” I say nervously.

“No. You won’t be seeing her again. Not if she sees you first.”

“Who is it then?”

“Nobody you know. Sup up and we’ll have a game of darts.”

And that’s all he will say. Of course it preys on my mind and I’m playing like a wanker. Two pints it costs me before Sid rubs the back of his hand against his mouth and looks at his watch.

“Right, off we go.”

It’s overcast and a bit sultry as we cycle along and I envy the way Sid handles his bike. With the ladder on my shoulders I’m wobbling all over the shop.