Human Universe

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2015

Text © Brian Cox and Andrew Cohen 2014

Photographs © individual copyright holders

Diagrams © HarperCollinsPublishers

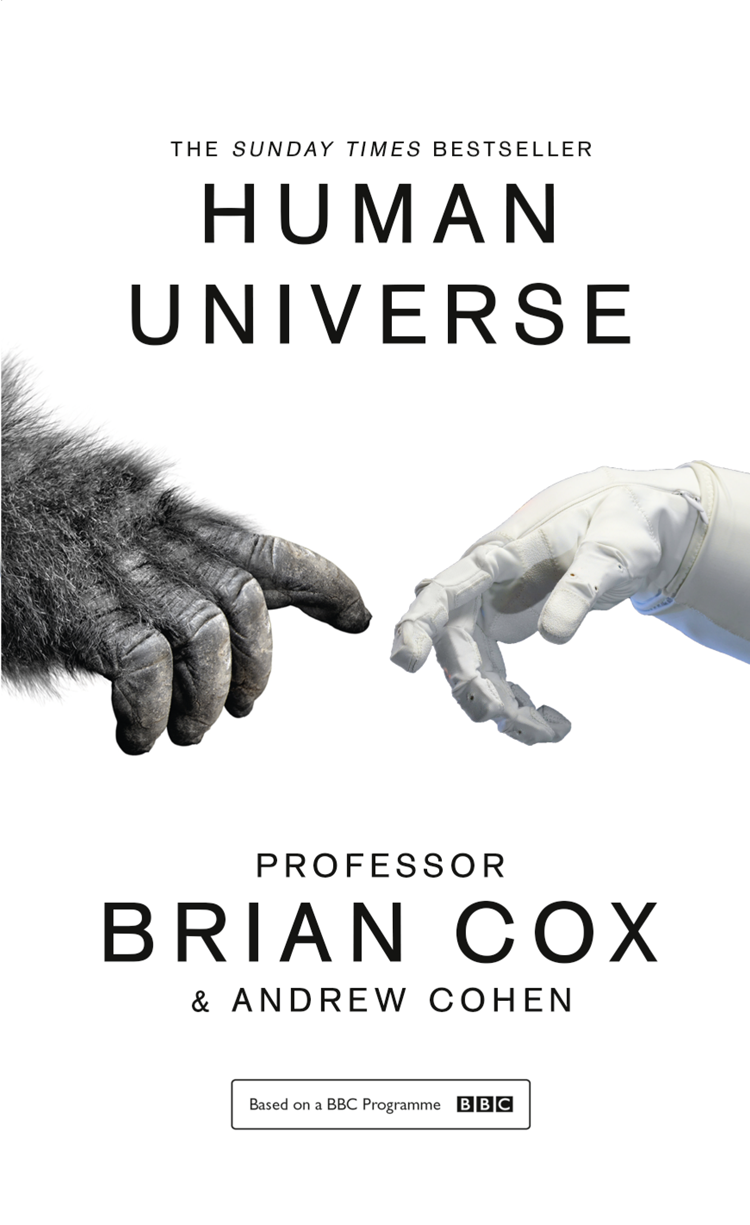

Cover photographs © Shutterstock (ape); © NASA (arm)

By arrangement with the BBC.

The BBC logo is a trademark of the British Broadcasting Corporation and is used under licence.

BBC logo © BBC 2014

The authors assert their moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-Book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008125080

eBook Edition © May 2015 ISBN: 9780008129798

Version: 2018-09-28

Praise for Professor Brian Cox:

‘Engaging, ambitious and creative.’ Guardian

‘He bridges the gap between our childish sense of wonder and a rather more professional grasp of the scale of things.’

Independent

‘If you didn’t utter a wow watching the TV, you will while reading the book.’

The Times

‘In this book of the acclaimed BBC2 TV series, Professor Cox shows us the cosmos as we have never seen it before – a place full of the most bizarre and powerful natural phenomena.’

Sunday Express

‘Cox’s romantic, lyrical approach to astrophysics all adds up to an experience that feels less like homework and more like having a story told to you. A really good story, too.’

Guardian

‘Will entertain and delight … what a priceless gift that would be.’

Independent on Sunday

Dedication

From Brian

To George Albert Eagle:

It’s your future, little boy.

From Andrew

To my soulmate Anna, my beautiful children Benjamin, Martha and Theo, my wonderful mum Barbara, my brothers Paul and Howard and all of the ‘small creatures’ whom I am lucky enough to have with me in the vastness.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for Professor Brian Cox

Dedication

Where are We?

Oakbank Avenue, Chadderton, Oldham, Greater Manchester, England, United Kingdom, Europe, Earth, Milky Way, Observable Universe …?

Off Centre

Changing Perspective

Outwards to the Milky Way

Searching for Patterns in Starlight

Beyond the Milky Way

The Great Debate

The Political Ramifications of Reality, or ‘How to Avoid Getting Locked Up’

The Happiest Thought of My Life

A Day Without Yesterday

Are We Alone?

Science Fact or Fiction?

The First Aliens

Listen Very Carefully

The Golden Voyage

Alien Worlds

The Recipe for Life

Origins

A Brief History of Life on Earth

A Briefest Moment in Time

So, are We Alone?

Who are We?

Spaceman

Apeman

Lucy in the Sky

From the North Star to the Stars

Climate Change in the Rift Valley and Human Evolution

‘An Unprecedented Duel with Nature’

Farming: The Bedrock of Civilisation

The Kazak Adventure: Part 1

Intermission: Beyond Memory

The Kazak Adventure: Part 2

Why are We Here?

A Neat Piece of Logic

New Dawn Fades

The Rules of the Game

Nature’s Fingerprint

A Brief History of the Snowflake

How the Leopard Got Its Spots

A Universe Made for Us?

A Day Without Yesterday?

What is Our Future?

Making the Darkness Visible

Sudden Impact

Seeing the Future

Science Vs. Magic

The Wonder of It All

Dreamers: Part 1

Dreamers: Part 2

The End

Plate Section Credits

Picture Section

Footnotes

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Authors

About the Publisher

WHAT A PIECE OF WORK IS A

MAN, HOW NOBLE IN REASON,

HOW INFINITE IN FACULTIES,

IN FORM AND MOVING HOW

EXPRESS AND ADMIRABLE, IN

ACTION HOW LIKE AN ANGEL, IN

APPREHENSION HOW LIKE A GOD!

THE BEAUTY OF THE WORLD,

THE PARAGON OF ANIMALS –

AND YET, TO ME, WHAT IS THIS

QUINTESSENCE OF DUST? MAN

DELIGHTS NOT ME – NOR WOMAN

NEITHER, THOUGH BY YOUR

SMILING YOU SEEM TO SAY SO.

HAMLET

What is a human being? Objectively, nothing of consequence. Particles of dust in an infinite arena, present for an instant in eternity. Clumps of atoms in a universe with more galaxies than people. And yet a human being is necessary for the question itself to exist, and the presence of a question in the universe – any question – is the most wonderful thing. Questions require minds, and minds bring meaning. What is meaning? I don’t know, except that the universe and every pointless speck inside it means something to me. I am astonished by the existence of a single atom, and find my civilisation to be an outrageous imprint on reality. I don’t understand it. Nobody does, but it makes me smile.

This book asks questions about our origins, our destiny, and our place in the universe. We have no right to expect answers; we have no right to even ask. But ask and wonder we do. Human Universe is first and foremost a love letter to humanity; a celebration of our outrageous fortune in existing at all. I have chosen to write my letter in the language of science, because there is no better demonstration of our magnificent ascent from dust to paragon of animals than the exponentiation of knowledge generated by science. Two million years ago we were apemen. Now we are spacemen. That has happened, as far as we know, nowhere else. That is worth celebrating.

WHERE ARE WE?

We shall not cease from exploration,

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

T. S. Eliot

OAKBANK AVENUE, CHADDERTON, OLDHAM, GREATER MANCHESTER, ENGLAND, UNITED KINGDOM, EUROPE, EARTH, MILKY WAY, OBSERVABLE UNIVERSE …?

For me, it was an early 1960s brick-built bungalow on Oakbank Avenue. If the wind was blowing from the east you could smell vinegar coming from Sarson’s Brewery – although these were rare days in Oldham, a town usually subjected to Westerlies dumping Atlantic moisture onto the textile mills, dampening their red brick in a permanent sheen against the sodden sky. On a good day, though, you’d take the vinegar in return for sunlight on the moors. Oldham looks like Joy Division sounds – and I like Joy Division. There was a newsagent on the corner of Kenilworth Avenue and Middleton Road and on Fridays my granddad would take me there and we’d buy a toy – usually a little car or truck. I’ve still got most of them. When I was older, I’d play tennis on the red cinder courts in Chadderton Hall Park and drink Woodpecker cider on the bench in the grounds of St Matthew’s Church. One autumn evening just after the start of the school year, and after a few sips, I had my first kiss there – all cold nose and sniffles. I suppose that sort of behaviour is frowned upon these days; the bloke in the off-licence would have been prosecuted by Oldham Council’s underage cider tsar and I’d be on a list. But I survived, and, eventually, I left Oldham for the University of Manchester.

Everyone has an Oakbank Avenue; a place in space at the beginning of our time, central to an expanding personal universe. For our distant ancestors in the East African Rift, their expansion was one of physical experience alone, but for a human fortunate to be born in the latter half of the twentieth century in a country like mine, education powers the mind beyond direct experience – onwards and outwards and, in the case of this little boy, towards the stars.

As England stomped its way through the 1970s, I learned my place amongst the continents and oceans of our blue planet. I could tell you about polar bears on Arctic ice flows or gazelle grazing on central plains long before I physically left our shores. I discovered that our Earth is one planet amongst nine (now redefined as eight) tracing out an elliptical orbit around an average star, with Mercury and Venus on the inside and Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune beyond. The Sun is one star amongst 400 billion in the Milky Way Galaxy, itself just one galaxy amongst 350 billion in the observable universe. Later, at university, I discovered that physical reality extends way beyond the 90-billion-light-year visible sphere into – if I had to guess based on my 46-year immersion in the combined knowledge of human civilisation – infinity.

This is my ascent into insignificance; a road travelled by many and yet one that remains intensely personal to each individual who takes it. The routes we follow through the ever-growing landscape of human knowledge are chaotic; the delayed turn of a page in a stumbled-upon book can lead to a lifetime of exploration. But there are common themes amongst our disparate intellectual journeys, and the relentless relegation from centre stage that inevitably followed the development of modern astronomy has had a powerful effect on our shared experience. I am certain that the voyage from the centre of creation to an infinitesimally tiny speck should be termed an ascent, the most glorious intellectual climb. Of course, I also recognise that there are many who have struggled – and continue to struggle – with such a dizzying physical relegation.

John Updike once wrote that ‘Astronomy is what we have now instead of theology. The terrors are less, but the comforts are nil’. For me, the choice between fear and elation is a matter of perspective, and it is a central aim of this book to make the case for elation. This may appear at first sight to be a difficult challenge – the very title Human Universe appears to demonstrate an unjustifiable solipsism. How can a possibly infinite reality be viewed through the prism of a bunch of biological machines temporarily inhabiting a mote of dust? My answer to that is that Human Universe is a love letter to humanity, because our mote of dust is the only place where love certainly exists.

This sounds like a return to the anthropocentric vision we held for so long, and which science has done so much to destroy in a million humble cuts. Perhaps. But let me offer an alternative view. There is only one corner of the universe where we know for sure that the laws of nature have conspired to produce a species capable of transcending the physical bounds of a single life and developing a library of knowledge beyond the capacity of a million individual brains which contains a precise description of our location in space and time. We know our place, and that makes us valuable and, at least in our local cosmic neighbourhood, unique. We don’t know how far we would have to travel to find another such island of understanding, but it is surely a long long way. This makes the human race worth celebrating, our library worth nurturing, and our existence worth protecting.

Building on these ideas, my view is that we humans represent an isolated island of meaning in a meaningless universe, and I should immediately clarify what I mean by meaningless. I see no reason for the existence of the universe in a teleological sense; there is surely no final cause or purpose. Rather, I think that meaning is an emergent property; it appeared on Earth when the brains of our ancestors became large enough to allow for primitive culture – probably between 3 and 4 million years ago with the emergence of Australopithecus in the Rift Valley. There are surely other intelligent beings in the billions of galaxies beyond the Milky Way, and if the modern theory of eternal inflation is correct, then there is an infinite number of inhabited worlds in the multiverse beyond the horizon. I am much less certain that there are large numbers of civilisations sharing our galaxy, however, which is why I use the term ‘isolated’. If we are currently alone in the Milky Way, then the vast distances between the galaxies probably mean that we will never get to discuss our situation with anyone else.

We will encounter all these ideas and arguments later in this book, and I will carefully separate my opinion from that of science – or rather what we know with a level of certainty. But it is worth noting that the modern picture of a vast and possibly infinite cosmos, populated with uncountable worlds, has a long and violent history, and the often visceral reaction to the physical demotion of humanity lays bare deeply held prejudices and comfortable assumptions that sit, perhaps, at the core of our being. It seems appropriate, therefore, to begin this tour of the human universe with a controversial figure whose life and death resonates with many of these intellectual and emotional challenges.

Giordano Bruno is as famous for his death as for his life and work. On 17 February 1600, his tongue pinioned to prevent him from repeating his heresy (which recalls the stoning scene in Monty Python’s Life of Brian when the admonishment ‘you’re only making it worse for yourself’ is correctly observed to be an empty threat), Bruno was burned at the stake in the Campo de’ Fiori in Rome and his ashes thrown into the Tiber. His crimes were numerous and included heretical ideas such as denying the divinity of Jesus. It is also the opinion of many historians that Bruno was irritating, argumentative and, not to put too fine a point on it, an all-round pain in the arse, so many powerful people were simply glad to see the back of him. But it is also true that Bruno embraced and promoted a wonderful idea that raises important and challenging questions. Bruno believed that the universe is infinite and filled with an infinite number of habitable worlds. He also believed that although each world exists for a brief moment when compared to the life of the universe, space itself is neither created nor destroyed; the universe is eternal.

Although the precise reasons for Bruno’s death sentence are still debated amongst historians, the idea of an infinite and eternal universe seems to have been central to his fate, because it clearly raises questions about the role of a creator. Bruno knew this, of course, which is why his return to Italy in 1591 after a safe, successful existence in the more tolerant atmosphere of northern Europe remains a mystery. During the 1580s Bruno enjoyed the patronage of both King Henry III of France and Queen Elizabeth I of England, loudly promoting the Copernican ideal of a Sun-centred solar system. Whilst it’s often assumed that the very idea of removing the Earth from the centre of the solar system was enough to elicit a violent response from the Church, Copernicanism itself was not considered heretical in 1600, and the infamous tussles with Galileo lay 30 years in the future. Rather, it was Bruno’s philosophical idea of an eternal universe, requiring no point of creation, which unsettled the Church authorities, and perhaps paved the way for their later battles with astronomy and science. As we shall see, the idea of a universe that existed before the Big Bang is now central to modern cosmology and falls very much within the realm of observational and theoretical science. In my view this presents as great a challenge to modern-day theologians as it did in Bruno’s time, so it’s perhaps no wonder that he was dispensed with.

Bruno, then, was a complex figure, and his contributions to science are questionable. He was more belligerent free-thinker than proto-scientist, and whilst there is no shame in that, the intellectual origins of our ascent into insignificance lie elsewhere. Bruno was a brash, if portentous, messenger who would likely not have reached his heretical conclusions about an infinite and eternal universe without the work of Nicolaus Copernicus, grounded in what can now clearly be recognised as one of the earliest examples of modern science, and published over half a century before Bruno’s cinematic demise.

OFF CENTRE

Nicolaus Copernicus was born in the Polish city of Torun in 1473 and benefited from a superb education after being enrolled at the University of Cracow at 18 by his influential uncle, the Bishop of Warmia. In 1496, intending to follow in the footsteps of his uncle, Copernicus moved to Bologna to study canon law, where he lodged with an astronomy professor, Domenica Maria de Novara, who had a reputation for questioning the classical works of the ancient Greeks and in particular their widely accepted cosmology.

The classical view of the universe was based on Aristotle’s not unreasonable assertion that the Earth is at the centre of all things, and that everything moves around it. This feels right because we don’t perceive ourselves to be in motion and the Sun, Moon, planets and stars appear to sweep across the sky around us. However, a little careful observation reveals that the situation is in fact more complicated than this. In particular, the planets perform little loops in the sky at certain times of year, reversing their track across the background stars before continuing along their paths through the constellations of the zodiac. This observational fact, which is known as retrograde motion, occurs because we are viewing the planets from a moving vantage point – the Earth – in orbit around the Sun.

This is by far the simplest explanation for the evidence, although it is possible to construct a system capable of predicting the position of the planets months or years ahead and maintain Earth’s unique stationary position at the centre of all things. Such an Earth-centred model was developed by Ptolemy in the second century and published in his most famous work, Almagest. The details are extremely complicated, and aren’t worth describing in detail here because the central idea is totally wrong and we won’t learn anything. The sheer contrived complexity of an Earth-centred description of planetary motions can be seen in Ptolemy’s Model, which shows the apparent motions of the planets against the stars as viewed from Earth. This tangled Ptolemaic system of Earth-centred circular motions, replete with the arcane terminology of epicycles, deferents and equant, was used successfully by astrologers for thousands of years to predict where the planets would be against the constellations of the zodiac – presumably allowing them to write their horoscopes and mislead the gullible citizens of the ancient world. And if all you care about are the predictions themselves, and your philosophical prejudice and common-sense feeling of stillness require the Earth to be at the centre, then everything is fine. And so it remained until Copernicus became sufficiently offended by the sheer ugliness of the Ptolemaic model to do something about it.

Copernicus’s precise objections to Ptolemy are not known, but sometime around 1510 he wrote an unpublished manuscript called the Commentariolus in which he expressed his dissatisfaction with the model. ‘I often considered whether there could perhaps be found a more reasonable arrangement of circles, from which every apparent irregularity would be derived while everything in itself would move uniformly, as is required by the rule of perfect motion.’

The Commentariolus contained a list of radical and mostly correct assertions. Copernicus wrote that the Moon revolves around the Earth, the planets rotate around the Sun, and the distance from the Earth to the Sun is an insignificant fraction of the distance to the stars. He was the first to suggest that the Earth rotates on its axis, and that this rotation is responsible for the daily motion of the Sun and stars across the sky. He also understood that the retrograde motion of the planets is due to the motion of the Earth and not the planets themselves. Copernicus always intended Commentariolus to be the introduction to a much larger work, and included little if any detail about how he had come upon such a radical departure from classical ideas. The full justification for and description of his new cosmology took him a further 20 years, but by 1539 he had finished most of his six-volume De revolutionibus, although the completed books were not published until 1543. They contained the mathematical elaborations of his heliocentric model, an analysis of the precession of the equinoxes, the orbit of the Moon, and a catalogue of the stars, and are rightly regarded as foundational works in the development of modern science. They were widely read in universities across Europe and admired for the accuracy of the astronomical predictions contained within. It is interesting to note, however, that the intellectual turmoil caused by our relegation from the centre of all things still coloured the view of many of the great scientific names of the age. Tycho Brahe, the greatest astronomical observer before the invention of the telescope, referred to Copernicus as a second Ptolemy (which was meant as a compliment), but didn’t accept the Sun-centred solar system model in its entirety, partly because he perceived it to be in contradiction with the Bible, but partly because it does seem obvious that the Earth is at rest. This is not a trivial objection to a Copernican solar system, and a truly modern understanding of precisely what ‘at rest’ and ‘moving’ mean requires Einstein’s theories of relativity – which we will get to later! Even Copernicus himself was clear that the Sun still rested at the centre of the universe. But as the seventeenth century wore on, precision observations greatly improved due to the invention of the telescope and an increasingly mature application of mathematics to describe the data, and led a host of astronomers and mathematicians – including Johannes Kepler, Galileo and ultimately Isaac Newton – towards an understanding of the workings of the solar system. This theory is good enough even today to send space probes to the outer planets with absolute precision.