Botham’s Century: My 100 great cricketing characters

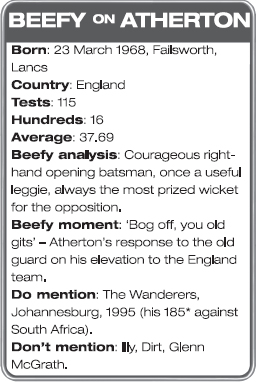

I know Mike himself believes that had he been allowed to pursue a new-broom policy without interruption, England might have made more progress more quickly. Then again, he never counted on the dirt-in-the-pocket affair during the Lord’s Test against South Africa in 1994 that effectively handed over the final say in selection to Raymond Illingworth, with whom he was subsequently to fight and lose too many battles over personnel.

I do think that one of the reasons the captaincy got to him in the end was that he didn’t feel able to communicate with or confide in guys like myself from a slightly older generation who might have been able to offer advice in certain situations. But whether he was right or wrong, his attempt to put his own mark on things from the start, whatever the fall-out, offered an insight into the single-mindedness that is at the core of his character.

In certain situations, of course, for single-mindedness read bull-headed obstinacy. First, consider events at Lord’s in ‘94, when he was spotted on television seeming to apply dust to the ball in what could only be described as suspicious circumstances, then copped a fine after he admitted to not telling the match referee Peter Burge exactly what he was carrying in his pockets at the time. The cricketing public were split right down the middle over whether he should quit the job, and even some of his closest friends thought he would. It took a certain kind of dog-with-a-bone stubbornness to hold on to the captaincy and his sanity while the debate raged around him. In the end he felt that carrying on was the right thing to do for the good of the side. Understanding what kind of scrutiny he was bound to be under from then on, that was an extremely courageous call.

A little more than a year later, as we went head-to-head in the Cane rum & Coke challenge to celebrate his marathon 185 not out to save the Wanderers Test against South Africa, one of the things Athers revealed to me was how much he regretted bring economical with the truth when interviewed by Burge. He genuinely panicked, I believe, and no matter how hard he tried to rationalize his actions subsequently, I don’t believe he will ever be able to rid himself of the feeling that he let himself down badly that day.

Courage, stubbornness, obstinacy, bravery. They say that a cricketer’s batting gives the clearest insight into his character; has there been a more transparent case of someone whose batting was so obviously what made them tick? Athers loved a fight; the tougher the opponent, the more he relished the challenge and, no matter what personal differences might have arisen, the longer he carried on the more his players respected him for it.

Take a look through memories of some of his most defiant innings, such as the aforementioned epic at The Wanderers to snatch the most unlikely draw. And later, to his great delight, painstaking hundreds against West Indies at the Oval and Pakistan in Karachi in 2000 to secure historic wins for his side. The vision of the full face of the bat comes inexorably towards you time and again, only occasionally barged out of the way by a full-on glare at Allan Donald, Curtly Ambrose, Glenn McGrath or Wasim Akram, or the exquisite execution of the off-side drives he unleashed with drop-dead timing when at the very top of his game.

As if the mere statistics of these and other achievements were not enough, remember this: for almost all of his career, Athers suffered from back pain that could only be kept at a tolerable level by a constant diet of painkillers which occasionally made him nauseous and cortisone injections that carried a significant health risk. He rarely mentioned his back, never made a fuss about it, and was rightly proud of the fact that he was fit enough to captain England in 52 successive Tests. A lesser character would never have come close.

Away from the fray, and for some reason I suspect we shall never fully understand, Athers put up barriers to people which he would only raise when he was absolutely sure he could trust someone. You could see why sometimes that would alienate, antagonize and offend people, and there is no doubt that at times he suffered because of it. I admit that at first I just didn’t know how to take him. But, as I came to know him better later in his Test career, I realized that the stern-faced exterior that made many misread him as aloof was probably only the defence mechanism of a paralyzingly shy person.

What I do know is that, during the second half of the 1990s, no side in world cricket relied so much upon the efforts of one man as did England. The rule of thumb during that period was that once the captain got out it was ‘man the lifeboats’. How richly deserved were the rewards that finally came the way of unquestionably the most complete England batsman of his generation.

Douglas Bader

One of the most enthralling evenings of my life was spent talking with, but mainly listening to, the amazing World War II fighter pilot, Douglas Bader.

Bader is remembered as the man who taught himself not just to walk again, but also to fly again during the Battle of Britain after losing both legs in a flying accident in 1931. His extraordinary courage and determination gained an international audience through Kenneth Moore’s portrayal of him in the successful film, Reach for the Sky. What is not so well known is that Group Captain Sir Douglas Bader, CBE, DSO, DFC – to give him his full title – was an outstanding sportsman. The accident – ‘my own bloody stupid fault’ – after attempting a low roll at 50ft in a British Bulldog biplane at the civilian airfield of Woodley, near Reading, came the week after he played fly-half for Harlequins against the Springboks, and just before his expected selection for the England debut against South Africa.

I was in my third summer as an England cricketer when Douglas Bader rang me out of the blue. I’d met him once before, very briefly. He’d been to the cricket, liked the way I played the game, heard that I was attempting to qualify for a pilot’s licence, and wondered whether I’d like to pop round to his mews house in London for a drink. I was round like a shot. As when I met Nelson Mandela, I was immediately aware that I was in the presence of someone very special. I couldn’t imagine what it must have been like to have lost both legs at the age of 20 with the sporting world his for the taking. He was a talented cricketer, and had captained the 1st XI at St Edward’s School, Oxford as an attacking bat and fast-medium bowler. The summer before his accident, Douglas top-scored for the RAF with 65 against the Army, in what was then a first-class fixture. But there was no moaning about his bad luck, nor any hint of regret at what fate had dealt him, or any sense of his being ‘disabled’.

The only problem was that he wanted to talk about sport – cricket, rugby and golf – while I wanted to know what it was like to fly a Spitfire and be in a dogfight. As ever, Douglas Bader’s persistence won the day. I was astonished about his knowledge of sport, and fascinated at his fight to become a decent golfer after his accident. He was determined to compete at some sport, now that rugby and cricket was lost to him, and at first it was an unequal struggle. Every time he swung the club, he would end up in a heap. As with everything else he tried, his simple refusal to be beaten by his disability enabled him to succeed in the end. Indeed, when I told him of my own concern about missing out on a licence because of my colour-blindness, he let me in on a little secret. He also suffered.

Eventually, by way of discussing the film Reach for the Sky, I managed to coax some recollections of life in the air during World War II – being shot down, getting replacement legs flown out to the French Hospital where he was prisoner so he could attempt to escape, and his days in Colditz Castle. He felt that the movie had rather glamourized the Battle of Britain, suggesting there was not a lot of romance involved in the experience of fighting for your very existence. One of his abiding memories was just how tiring it all was. The RAF were running out of pilots and planes; every time the Germans attacked, the squadrons were ‘scrambled’ and up they went, again and again. The only respite came when the weather was bad, and the pilots would lie back on their beds, exhausted.

Douglas was much older than most of the pilots, who were in their teens or early twenties. His life in the services seemed to have ended in late 1931 with his accident, but after the outbreak of world war in 1939 a chronic shortage of experienced pilots, his desire to get back in the air and his persistence in trying to persuade the RAF that he could still do a job earned him another chance to fly. He told me to forget the war films in which the fighter pilots stayed in the air for hours with endless supplies of ammunition. The actual firing time available in the spitfire was about three and half seconds. If you weren’t on the ball and your aim was off, you would run out of ammo before you had time to blink. The fuel gauges weren’t always that accurate either, and pilots would end up having to bale out over the sea or find a field somewhere near home. It also surprised me when he told me he was not fighting an anonymous enemy; on many occasions he could almost see the eyes of German pilots that were trying to shoot him down.

Douglas Bader must have been an inspiration to the RAF Young Guns, as much as he was to the next generation in Britain when his story was told. Douglas was a guy who was determined to succeed in whatever he did. He was so enthusiastic and wholehearted and did not know any other way. But he also had a very practical view of life. That was evident even when he was awarded his knighthood. Buckingham Palace called to make sure that, with his tin legs, he would be able to kneel on the cushion when the Queen touched his shoulders with the sword. Douglas replied that he wasn’t sure but would go away and have a go. ‘No good,’ he told the Palace, ‘I’ve had two goes at it and fallen on my arse both times!’

I enjoyed my evening and it convinced me this was someone who would have been a lot of fun to be with, especially in his younger days. Those who think I’m not a fan of old ways and the older generation are way off the mark. It’s the person who impresses or distresses me. Age has nothing to do with it.

I’m not sure today’s youngsters appreciate the sacrifices made by Douglas’ generation. I did, not only because of the films. My parents had been through the War. It’s 60 years ago now and I suppose those days have passed from the memory into history. Not that Douglas was one for living in the past. I was rather saddened a few years ago when the television programme, Secret Lives, tried to slur his reputation. His widow Lady Joan Bader said at the time, ‘People either say he was a super guy or an absolute bastard.’ I’m firmly in the ‘super guy’ camp. I’m sure there was more of a touch of arrogance in his younger days, but so what? He lived life to the full. There are always people ready to try and bring down those who have made the most of their time and refuse to compromise or be beaten.

My evening with Douglas Bader was an experience I will always cherish.

Ken Barrington

Kenny Barrington and I shared a birthday, 24 November, and a whole lot more besides.

People often ask me who was my favourite cricketer when I was first getting interested in the game. Bearing in mind the way I played, most assumed that I took my lead from somebody like Sir Gary Sobers, the greatest all-rounder I ever saw, or a swashbuckling cavalier like Ted Dexter.

But when I told them Kenny Barrington was my favourite, almost all were nonplussed. Kenny could play. Make no mistake about that.

He scored 20 Test hundreds and nearly 7,000 runs in all, and if you look at the list of those batsmen with the highest Test averages of all time you’ll find K. F. Barrington at number six, with an average of 58.67. To put that in its proper context, of the all-time greats he made his runs at an average higher than Wally Hammond, Sobers, Jack Hobbs, Len Hutton and Denis Compton, and of the modern giants, higher than Sachin Tendulkar, Steve Waugh, Brian Lara and Viv Richards. He could play all right.

The problem for those who assume that someone like me takes their lead from a similar player is the way Kenny generally batted. If you wanted to be kind, you’d call him obdurate. Others, less kind, said that on occasion, watching Kenny grind out the runs was like watching your fingernails grow.

But what I loved about The Colonel, as he was known and revered, was neither the number of runs he made nor the way he made them. It was simply the look of him. Had they made a film of his life, Jack Hawkins would have been perfect for the part. Kenny brushed his teeth like he was going to war. When he marched out to bat, he looked ready to take on an army single-handed. With his great, jutting jaw and hook nose almost touching in front of gritted teeth, the expression on his face said, ‘You’ll never take me alive,’ and it made an impression on the young Botham that deepened as I grew to know him personally in his roles as England selector and later coach.

Before I met Kenny I was actually quite apprehensive about the kind of bloke he might turn out to be. Bearing in mind what he looked like in action, scary was the word that crossed my mind. But it didn’t take me long to realize that although he was ice-cold on the outside, the guy had the warmest heart in cricket. What is more, he was held in exactly the same high regard wherever he went. There wasn’t a dressing room in the world where Kenny wasn’t welcome.

One of the reasons was the humour that went with him; some of it was even intentional. The rest, down to the fact that for years he waged a losing battle with a tongue that simply refused to say what he wanted. ‘Carry on like that,’ he told me once, ‘and you’ll be caught in two-man’s land.’ ‘Bowl to him there,’ he urged, ‘and you’ll have him between the devil and the deep blue, err … sky.’

But he was far more than a figure of fun. In fact, I would go so far as to say that had untimely death not cut short his second career, I believe Kenny would have become a truly great coach. Confidant, technician, helper and motivator; these were his responsibilities as he saw them. And he was excellent at all of them.

The last thing a player wants to hear from a coach is the sentence that begins with the dreaded words: ‘In my day.’ I never once heard him utter them. He was happy enough to talk about the past and his career as a player – and I for one never tired of hearing him recount hitting the mighty Charlie Griffith back over his head for the six with which he reached a century against the West Indies in Trinidad on the 1967–68 tour, his last in Test cricket – but the crucial thing was that he only did so when asked.

The key to Kenny’s success as a coach was that he never spoke down to his players. In later years it became the norm for the coach to adopt a much more authoritarian approach and believe they should ‘run’ the team. Kenny never told anyone to ‘do this’ or ‘do that’; instead, he posed the question: ‘What if you did this?’ or ‘How would you feel about doing that?’, and we responded because we all felt our opinions were being considered.

As a technical coach he was brilliant at spotting little problems and addressing them before they took hold. On my second tour of Australia in 1979–80 he corrected something in my batting that altered the way I played for the rest of my career. I used to take guard on middle-and-leg stumps, then just before the bowler reached the moment of delivery I would move back and across to get right in line. Early in the tour I found I was getting out lbw on a regular basis and couldn’t understand why. The incident that brought things to a head happened in Adelaide, when a South Australian quickie by the name of Wayne Prior won an lbw decision against me with a ball I was convinced was drifting down the leg side.

Kenny saw I was cross when I got back to the dressing room, but when I watched the replay on the television link-up I was amazed to see that I was in fact plumb. Kenny waited until I’d calmed down then quietly took me to one side and suggested we have ten minutes with the bowling machine in the nets. That was all it took. He spotted that I was moving too far across my stumps before the bowler let go, so that balls I thought were going to miss the leg stump were actually hitting about middle and leg.

‘Try taking leg stump guard,’ he said, and for the rest of my career, apart from when specific situations demanded otherwise, I did.

He became a massive influence on me personally. Which is why his sudden death during the Barbados Test on the 1980–81 tour of the West Indies hit so hard. When I took the phone call from A. C. Smith, our manager, I just didn’t want to believe what he was telling me – that Kenny had suffered a heart attack in the night. My immediate reaction was that we shouldn’t play the next day’s cricket, but after a team meeting to discuss what we should do, it soon became clear that the only thing to do was to carry on, for Ken.

I have often wondered how my career and my life might have been different if Kenny had been around to guide me. Regrets, I’ve had a few, etc. But there were times, particularly following the amazing triumphs of 1981, that I allowed success to go to my head and in what came to be known as the ‘sex, drugs and rock’n’roll’ days of the mid-80s. Would Kenny have been a sobering influence when I needed one? Many friends of mine believe Kenny was taken at the very time I needed someone like him to make me see sense. All I know is that I missed him terribly.

Bill Beaumont

I regard Bill Beaumont as the best ambassador for British sport there has ever been. After his distinguished rugby career as captain of England and the British Lions, Bill has continued to give of his time and considerable experience to rugby as it struggled with professionalism.

The name of Beaumont is linked with mine because we spent eight years in opposition as the team captains in A Question of Sport with David Coleman in the chair trying to keep order, but our first memorable evening was years earlier, on the night that Bill led England to their first Grand Slam for 23 years at Murrayfield.

I was in the company of my father-in-law, Gerry a big rugby nut, and Tony Bond, the England centre who had broken his leg at the start of the Five Nations against Ireland. He was still on crutches. In the lobby of the team hotel, the North British, Bill saw us and invited us into the official reception for a drink. Standing around with some of the England players, chatting and enjoying a glass, we were pounced upon by some Scottish MacJobsworth and told that I had to leave. I explained I was not a gatecrasher; Bondie had been a member of the England squad until his injury, and we had been asked in by the victorious England captain and coach, Mike Davis, so I thought that would be the end of the matter. Not with this Rob Roy.

‘We are paying for this function, and we’ll decide who comes in. You are not wanted, out you go.’

‘Well, if you paid for this gin and tonic, you’d better have it back,’ I replied and I promptly tipped it over his head.

The trio of us were frog-marched out, closely followed by most of the England squad, who decided to join us. That’s why the England captain spent most of the evening sitting on the stairs outside the Scottish Rugby Union reception. Every so often, one of the players would come out with a tray of drinks to keep us going. It was the start of a very memorable evening.

Bill was forced to retire from the game a couple of years later after being told that another kick on the head could have serious consequences. His England career finished at Murrayfield, but his last appearance at Twickenham saw that famous half-time streak from the well-endowed Erica Roe. Bill had his back to the action and couldn’t understand why his emotional team-talk was not being received with the same intense concentration as usual, until his scrum-half, Steve Smith, explained: ‘Sorry Bill, but some bird has just run on wearing your bum on her chest!’

Bill and I enjoyed a tremendous rivalry during our time on A Question of Sport. Bill is as competitive as me, and his sporting knowledge is extensive. His three specialist subjects were cricket, rugby and motor racing – he loved showing up my weakness on the cricket questions. But on golf, or soccer, he didn’t have a weakness. He was hard to beat. I’m glad that we both decided to call it a day together after eight years. I couldn’t have imagined doing the show without him.

Despite his good nature, Bill was not beyond some skullduggery. I remember the night when Gazza (Paul Gascoigne) was on the show. He wasn’t supposed to be drinking, but was getting fed up with the taste of bitter lemon and tonic water. As Gazza was going to be a member of Bill’s team, when he asked if there was anything else non-alcoholic he could try, I suggested advocaat. I knew the taste would disguise the alcohol and its effects were slow-acting. Gazza promptly drank a bottle and half in about an hour and half before the show. Imagine my horror when I discovered that Bill had worked out what was going on and I found myself with Gazza on my team. We lost, and the show took twice as long as normal to record.

One of the funniest holidays Kath and I ever had was with Bill and his wife, Hilary, when we went to Courcheval in the Alps to learn to ski. Because of the insurance, I was never allowed to ski when I was playing. Can you imagine Beaumont and Botham on the nursery slopes? Even trying to get our skis on took half a morning and nearly caused an avalanche. We had these all-in-one ski suits and as we came down the nursery slopes rather sedately, all these little kids, some aged about three, were shooting past, weaving in and out, and cutting across us, regularly causing us to fall apex over tit. After a couple of days of this, Bill had had enough and was looking for an opportunity to spear someone with his ski stick. The trouble was that every time he made that sort of move, over he went. I’ve never spent so much time on my backside.

Lunch on the third day was the turning point. After a couple of bottles of Dutch courage, Bill and I decided to leave the nursery slopes and graduate to something a little more testing. We felt reasonably confident as we’d just about learnt to keep upright in a straight line. It hadn’t occurred to us that stopping was another crucial skill that didn’t come naturally. We both realized our predicament at about the same time … I can tell you that Beaumont and Botham out of control on the pistes is not a pretty sight.

Franz Beckenbauer

Just one of the true giants of football to whom I was compared during my all-too-brief reign as the leading centre-half in the English game. Norman ‘bites yer legs’ Hunter, Ron ‘Chopper’ Harris, and Vlad ‘on me ’ead son’ the Impaler, were among the others. The debate rages on.

Actually, I might have been good enough to have made a professional career in soccer. When I was 15, Bert Head, the Crystal Palace manager and, clearly, one of the shrewdest judges around, thought enough of my potential to offer me a trial at Selhurst Park.

I’d been playing for Somerset Schools and training with Yeovil Town for a couple of years. At the time, the manager there was Ron Saunders, who went on to become one of the best in the league, and he recommended me to Bert.

In the end I chose cricket, and the decision to do so came about as a result of me listening to my father, Les, for once. He was a top all-round sportsman himself, who’d represented the navy at soccer – good enough for Bolton Wanderers to try and prise him away from a life on the ocean waves – and he was the one I turned to when the time came for me to pick which horse to ride.