Blow by Blow: The Story of Isabella Blow

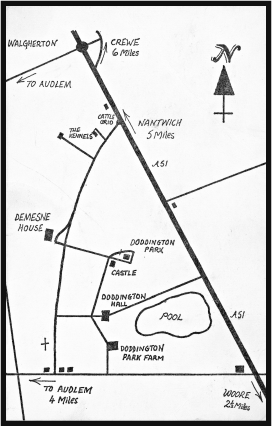

A hand-drawn map of the Doddington estate.

By the outbreak of the Second World War the Delves Broughton family estates had been reduced to just over a thousand acres: the deer park around Doddington Hall and one nearby farm.

In 1940 Vera divorced Jock. In her divorce petition, Vera cited Jock’s affair with Diana Caldwell – a glamorous blonde divorcée, almost 30 years younger than him, who would become his second wife. With Britain desperately fighting for survival against Nazi Germany, Jock and Diana decided to leave England and go to Kenya, where Jock had acquired a beef and coffee estate.

Jock believed that his colonial adventure was going to give him a chance not only to make a fresh start with his beautiful young wife but also to allow him to contribute to the war effort with his farming. It did not hurt that it was also immensely cheap to live very well in Kenya. Jock and Diana were soon partying with the freewheeling ‘Happy Valley’ set of decadent colonials who drank heavily, took drugs and slept with each other.

Diana fell in love with Josslyn Hay, the Earl of Errol, a famous seducer of other men’s wives, who had been married three times himself. Diana and Lord Errol started a passionate and very public affair. Three months later, Errol was found, shot dead in his car, just 2½ miles from Jock’s house outside Nairobi; earlier that night, at 3 a.m., he had dropped off Diana.

Deer beside the lake in the park at Doddington.

Jock, the humiliated and cuckolded husband, was the obvious suspect and he was subsequently charged with Errol’s murder. At the trial he put in a witty and polished performance in the witness box – and was acquitted. But the blanket coverage of the trial both in Kenya and the United Kingdom and the associated scandal destroyed him. After the trial, he headed back home, and when he arrived at the dock in Liverpool he was met by agents investigating his dubious insurance claims.

A few months after his return to England, in December 1942, Jock committed suicide at the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool with a morphine overdose. He left behind a tangled legacy – and, as Issie often noted, 60 pairs of shoes.

CHAPTER FOUR

Evelyn

The upshot of all this was that what should have been a huge inheritance for Jock’s son, Evelyn (Issie’s father), was massively reduced. The vast estate was less than 10 per cent of its former size, a ‘mere’ 1000 acres. If an estate that size was to continue to support even a much reined-in Delves Broughton lifestyle, a major rethinking of how the estate functioned as a business would clearly be necessary.

The park at Doddington had been occupied by over 1100 Polish refugees in Nissen huts during the war. They stayed on for a few years afterwards, providing Evelyn with a meagre but welcome income from the government. But with the army no longer requiring Doddington Hall itself, Evelyn leased it out to Goudhurst Ladies College and in 1946 most of the contents of Doddington were sold at auction. This was a common occurrence at the time, when many stately homes were turned into prisons for young offenders, schools – or simply demolished and the contents sold off.

After the Polish refugees left, Evelyn, who was brutally practical, set about turning his remaining land into a modern farm. He killed the 300 fallow and red deer in the park, cut down many of the trees planted by ‘Capability’ Brown, now mature and valuable as hard timber in the post-war reconstruction, and then ploughed the park up and turned it into farmland.

The decision paid off. Over the next 20 years he made Doddington Park Farm into a state-of-the-art dairy, beef, corn, sheep and potato farm – and a great commercial success. Isabella described it as being run on factory lines.

Evelyn’s greatest agricultural success was growing potatoes. They became a very successful cash crop, especially after he won a contract to supply potatoes to Walkers Crisps. Once, he told me, a manufacturer desperate for potatoes had paid him £9000 in cash for a large pile of spuds. Evelyn, who had a pathological aversion to paying tax, did not pay the money into the bank, thereby obviating the need to pay any levies on the sum, which gave him great pleasure. The local bank manager in Nantwich mournfully commented, ‘Sir Evelyn, we have not seen you in here for such a long time.’

On other occasions he flew with Issie to Switzerland, where he would deposit the potato money into his Swiss bank account and return the following day. For the night Issie and her father would stay in luxury at the Palace Hotel. A Swiss bank account was a not unusual accessory for a rich man at the time – my father, far less wealthy, opened a Swiss account and deposited £250 – but it was illegal.

Evelyn’s austerity drive complemented his miserly streak. Once, Issie was invited to stay at Chatsworth, the home of the Duke of Devonshire. One of her best friends from Oxford, Anthony Murphy, had married the Duke’s youngest daughter. Issie asked her father for some money to tip the butler at the end of the weekend. Evelyn reluctantly agreed – but insisted Isabella write him a cheque for the £10 he gave her. On her return to Doddington, Evelyn plied Isabella for details on the set-up at Chatsworth, particularly wanting to know how many footmen there were. When he presented Isabella’s cheque at the bank to get his £10 advance back, the cheque was returned. Isabella recalled with glee that her father tried to re-present it several times before giving up.

Issie put a cheerful gloss on her father’s penny-pinching ways, but his habits often made life difficult or socially embarrassing for her. In 1979 she was invited by her friend Mimi Lady Manton to stay with her at her home in Yorkshire. She had a special guest coming – the unmarried Prince of Wales. She told Issie, ‘You have goofy teeth and will make him laugh.’

When Issie excitedly told her father that she was going to the same house party as Prince Charles, she asked for some money to buy an evening dress, a not unreasonable request.

Her father’s reply was, ‘Beg, steal, or borrow.’ And he meant it. He was not going to give her any money for mere fripperies.

Evelyn may have been stingy but he did have a sense of propriety – he rejoined Lloyds Insurance to pay off his father’s frauds, he claimed.

His big cut-back was to move into what had been the head gardener’s cottage, located about half a mile from the Hall. Isabella was to resent this all of her life. She described it to me as ‘a hideous pink house’ with a ‘1950s wing’ and ‘a carport’ which her father built onto it. Evelyn had decorated it with pictures bought ‘from Boots the Chemist’, according to Issie. His favourite was a painting of a scantily clad Caribbean girl weaving a basket – now in the possession of Isabella’s youngest sister, Lavinia. Issie told me that she always knew her parents had ‘bad taste’.

Isabella’s mother, Helen Shore.

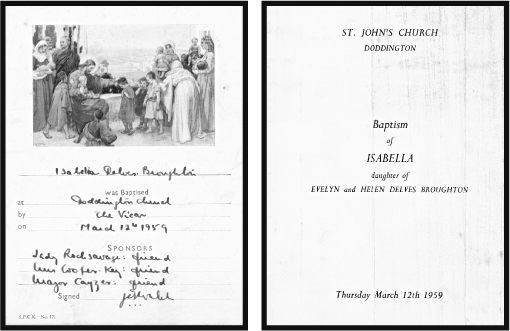

Isabella’s baptism certificate. She was baptised on Thursday 12 March 1959, at the age of four months.

Evelyn admitted freely – almost proudly – that he was a cultural philistine, and this would bring him into sharp conflict with Isabella, who grew up as a child yearning for the lost beauty and glamour of Doddington Hall, ever-visible just across the fields.

By 1955, with Doddington running successfully, Evelyn, now aged 40, married Helen Shore. The daughter of a successful Manchester greengrocer family, she was ambitious and clever, and had been called to the Bar in 1951 at the age of 21. Evelyn had in fact been briefly married before, to Elizabeth Cholmondley, so he and Helen had to content themselves with a service of blessing at St Simon the Zealot’s church in Chelsea in 1955.

At the time of Isabella’s birth, Evelyn was 43 and Helen 28. Isabella was born three years after the marriage. Julia was born in 1961 – and then in 1962 the longed-for son and heir, John Evelyn, finally arrived.

The birth of a son settled all the inconvenient questions of inheritance that had been lurking unspoken in the background following the birth of the two girls, Isabella and Julia. It was quite clear now what would happen to Doddington Park – it would pass to John on his father’s death. He may not have been able to afford to live in the splendour of the big house, but the prospect of a male heir redoubled Evelyn’s determination to work at his farm. After a generation of scandal and financial disaster, it seemed that things might finally be starting to turn the corner for the Delves Broughtons.

Newborn Isabella at the London clinic with her mother, who has had her make-up and hair done, which Issie later strongly approved of.

One can understand, then, why the loss of Johnny was so devastating. Evelyn belonged to an age and a class which valued males more highly than females. He did little to spare his grieving daughter’s feelings on this account.

After Johnny’s death, he considered leaving Doddington Park to his closest male relative, Simon Fraser, Master of Lovat, the eldest son of his sister Rosie, and himself in line to inherit from his father, Lord Shimi Lovat. But then Evelyn did some research on some family assets managed by his nephew and was not impressed. Simon was struck off the list.

Another possible beneficiary, he announced to Helen when he came down to breakfast one morning, was Trinity, his old college at Cambridge. He had known happiness there, he said. His three daughters, sitting there eating their cornflakes, were not considered at all.

There was a curious dichotomy in his relationship with Isabella – and all his daughters – for while, ultimately, he betrayed them and badly let them down, there were tender moments of affection. Isabella often accompanied Evelyn on his agricultural rounds, for example, an important ritual that bonded her closely to her father and allowed her to feel loved by him. From the age of 14 she would drive along the internal farm roads to pick him up for lunch every day in the battered old farm car. And Evelyn was, to his credit, not always quite as distant to his children as many upper-class fathers of the age. As her father’s friend Major Peter Ormerod recalled, Evelyn would dress up as Santa Claus at Christmas parties at the house and distribute presents to the children – and to the mothers give ‘out of his sack a half bottle of champagne’.

Isabella with her mother and father, at the gardener’s cottage. In the background you can see the beef cattle.

Evelyn was not a bad man. His great fault was that he was weak.

CHAPTER FIVE

Poor Relations

Even as a child, Isabella was bedevilled by financial insecurity. She undoubtedly picked up her almost existential anxiety about money from her father, who, when he wrote to her at boarding school, would put in brackets next to each person’s name the total number of acres of land which they owned.

Issie measured herself against the wealth of others and found she came up wanting. She keenly felt the part of poor relation. While the Cholmondleys, for example, still lived in splendour in their very own castle, with a retinue of uniformed servants, the Delves Broughtons, by comparison, were holed up in the hated gardener’s cottage while the main house was occupied by a school. There were butlers and gardeners, to be sure, but the set-up was all too obviously being run on a shoestring by comparison to their far richer neighbours. Evelyn’s proud boast that the family had once been able to walk fourteen miles without straying off their own property made matters, if anything, even worse.

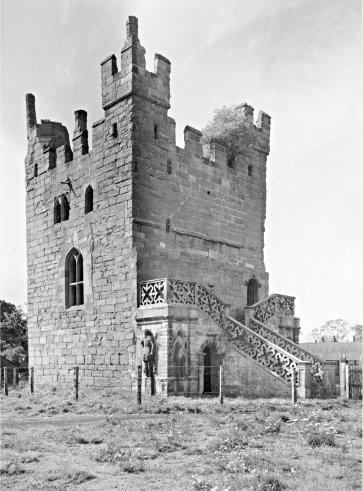

The gardener’s cottage so despised by Issie was, in fact, a perfectly agreeable and spacious four-bedroom house. Yet even today, with the once-magnificent big house boarded up in the distance, it still looks out of place, a curiously suburban, almost hacienda-style structure, parked incongruously next to a tumbledown pink sandstone castle tower dating back to medieval times.

Issie loved to play in this perilous, weed-filled tower, conducting dramatic re-creations of medieval rites and myths with her sisters as willing or unwilling participants, and it was an important part of the family’s history. At the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, John de Delves fought valiantly and he was later knighted by King Edward III and granted a licence to crenellate and fortify the tower. The tower was a formative element in Issie’s medieval aesthetic. Years later, the tower would be the inspiration for a ‘castle hat’ designed by one of Issie’s most famous discoveries, the milliner Philip Treacy.

The medieval castle in the grounds of Doddington Park, where Issie spent much time playing as a child.

The Broughtons had an-old fashioned disregard for modern health concerns. Isabella grew up enjoying fresh, unpasteurised, creamy milk straight from the house cow. Their farm manager, worried about the risk of catching tuberculosis, had his milk delivered by the milkman in a sanitised bottle. Throughout her life, Isabella would insist on the richest, full-fat milk.

Another family indulgence was cigarette smoking. Evelyn and Helen smoked heavily, though Evelyn eventually had to give it up when he began suffering bad emphysema. Married to me, Isabella would start smoking at breakfast – sometimes chain-smoking five in a row – ignoring my pleas and entreaties that it was damaging her health.

‘Detmar, you cannot talk, you smoke cigars,’ she would say airily, clouds of smoke billowing out from under her latest Philip Treacy hat.

‘But not for breakfast, Issie,’ I would retort, gasping for air. ‘And anyway, cigars are good for you – look at Churchill and Castro.’

Growing up at Doddington, Isabella often heard stories from the locals of her grandmother Vera’s menagerie at Doddington. Vera had kept a dazzling array of exotic animals, including Carroway birds, ostriches and honey bears, which would often escape to the village from the cages that can be seen at Doddington House to this day. Once a bear had to be lured down from the church steeple with pots of honey.

Isabella’s last memory of her beloved grandmother Vera was being with her while watching the news coverage of the assassination of Bobby Kennedy at her first-floor flat at 51 Eaton Square. Shortly afterwards, Vera died. When Issie and I were first married we lived a few hundred yards away from Eaton Square in Elizabeth Street, and when she was upset with me Isabella would go and sulk in the doorway at 51 Eaton Square, beneath Granny’s old flat.

After Vera’s funeral, Evelyn’s sister Rosie suggested that their mother’s ashes should be buried at the family church at Doddington. Evelyn flew into a rage and refused Rosie’s request. He told his sister, ‘If our mother had not divorced our father, none of the murder trial mess would have happened.’ The scars and shame of Kenya ran very deep for Evelyn.

* * *

Isabella was six years old when Lavinia arrived, and was attending Nuthurst school, the local private primary school in Nantwich, a few miles from Doddington. The school, which has since closed down, was a red-brick Georgian house with a white portico doorway in Hospital Street. Isabella enjoyed it and was popular with the other children and the teachers.

Her friends remember Isabella for ‘her mop of blonde hair’, and described Issie enjoying doing the washing-up at a schoolfriend’s party with her sister Julia.

Midway through Issie’s career at Nuthurst, a new teacher started. Arriving for her first day, Isabella, seeing that she looked a bit lost, greeted her with the words, ‘You must be new here. Let me show you around.’ It was typical of Isabella’s kindness and thoughtfulness to people, the teacher said.

Left to right: Lavinia, Helen, Julia and Isabella, at their home in Cadogan Square, London.

Young Isabella in her Nuthurst school uniform.

Isabella was, she added, ‘A little ray of sunshine.’

To occupy her children outside of term time, Helen, who had studied medieval history at school, encouraged them to look to their medieval roots. In addition to playing fantasy games in the tower, where she would make other children worship a plaque of a ‘goddess’, Isabella was often taken to nearby Audlem church, where she would make brass rubbings of her knightly ancestors’ tombs.

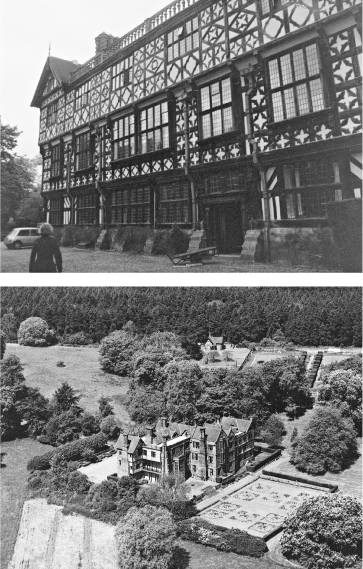

Once they went on a trip to the former family house, Broughton Hall. This single visit left a lasting impression on the young Isabella. For the rest of her life, she remained intrigued by the place, a sturdy black-and-white timbered building constructed in the 1450s. During the English Civil War in the 1640s, a young Broughton boy declared to the entering enemy Parliamentarian soldiers, ‘I am for the King!’ He was shot instantly, his blood flowing down the ornately carved staircase as he lay dying. As Isabella was absorbing all this history, her mother told her, ‘Well, Isabella, it is not yours any more,’ and took her home to the former gardener’s cottage.

Two views of Broughton Hall.

In the inexplicable way of such incidents, this cruel jibe about the lost Broughton fortune became a focal point for Isabella’s hatred of her mother. And in her escalating battles with her mother Isabella was to hone in on her mother’s weak spot: her bourgeois background.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги