Consumed: How We Buy Class in Modern Britain

CONTENTS

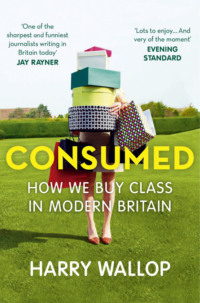

COVER

TITLE PAGE

INTRODUCTION

1. FOOD

2. FAMILY

3. PROPERTY

4. HOME

5. CLOTHES

6. EDUCATION

7. HOLIDAYS

8. LEISURE

9. WORK

CONCLUSION

NOTES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

INTRODUCTION

‘We are all middle class now,’ said John Prescott to howls of derision in 1997, in the run-up to the general election that swept Tony Blair into power.

Prescott was, of course, Blair’s bruising, working-class sidekick who had gone to sea at the age of 16 and worked his way up the ranks of P&O. With his pugnacious beliefs and mangled English, he was wheeled out to persuade old Labour voters that Blair, the first prime minister since Sir Alec Douglas-Home to attend a public school, understood their concerns. The idea that Prescott was middle class seemed as likely as finding caviar in Lidl.

But 15 years on, his astute comment has been proved correct, with the great majority of us considering ourselves middle class. Meanwhile he’s sitting in the House of Lords, the ultimate sanctuary of the ruling elite of Britain, and Lidl sells John West lumpfish caviar. Yours for £2.48 for a 50g tin.

The election was held on 1 May 1997. It was, I remember, a very warm day, and in glorious sunshine I cast my ballot for regime change, as nearly all students that day did. It was the summer of my finals at Oxford, and for a generation who had only ever known Margaret Thatcher and John Major things really could only get better, as D:Ream sang. My vote was not really political; it was generational.

That evening I went down to London to attend the dinner to celebrate my cousin’s 21st birthday. It was being held at White’s, the smartest of all London’s gentlemen’s clubs, a glorious early Georgian building on St James’s, which had once served as the unofficial headquarters of the Tory party and where the Prince of Wales had his stag night. The dress code, as it is always at gentlemen’s clubs, come rain or stifling heat, was jacket and tie. I turned up in a three-piece tweed suit. Nowadays I would call it vintage. Then, it was charity shop chic, bought in a second-hand outlet in Oxford for a student Chekhov play. It was, in reality, a 1950s garment, but accessorised correctly I was sort of passable as a turn-of-the-century Russian doctor hanging out near a cherry orchard. I thought I looked pretty stylish.

My father thought otherwise. Possibly the mildest mannered man you could imagine, he exploded with ill-concealed contempt, ending with the immortal lines uttered without any hint of irony: ‘Gentlemen do not wear tweed after six o’clock in London.’

Behind this temper was, I knew, a deep-seated disappointment that I had let him down. My entire upbringing had been an extended lesson in the British class system, and its tiny invisible rules, a living out of Nancy Mitford’s list of ‘U and non-U’ words to ensure my vocabulary did not embarrass any of the guests for tea. Debrett’s was occasionally brought down from the shelf to teach me how to address envelopes correctly to the assorted earls, countesses and viscounts from whom I had received Christmas presents. Mostly these were aunts and cousins. How to curtsy to royalty, eat asparagus and artichokes, pluck a pheasant, tip a gamekeeper, when to leave the room, what one wore – this was not some parlour game, this was just how I was brought up in west London in the 1970s and 80s. These rules were never drilled into me, they were merely taught alongside tying one’s shoelaces, riding a bicycle and asking to get down from the table. It seemed, as it always does for any child, normality itself. Whether one wore tweed after six, brown in town, if one called it ‘pudding’ or ‘dessert’ were things I was just meant to know. If I wanted to look like a tramp in my student flat, fine, but please God, not in White’s.

I had got it wrong and my father believed I had done so on purpose as some sort of silent political protest – though it was clearly laughable to suggest that wearing tweed in the grandest of all St James’s clubs was an act of solidarity with John Prescott.

I spent the entire evening fuming, as the grandees around me fumed too about how the incoming government was going to ruin Britain. The votes had yet to be counted, but the landslide was already inevitable. Change was in the air, but not in this privileged corner of SW1. Surely, I argued, in the summer of 1997 such niceties of class and of what gentlemen did or did not do were not just a decade out of joint, but a full century? Apparently not.

And 15 years later the niceties are still very much alive – just in a different form. Class has never gone away. Even after the years of never having it so good, the white heat of technology, the no turning back, 13 years of New Labour and, now, of being all in it together. If anything, it is more prevalent than it has ever been and it touches nearly everyone, including millions who consider class an irrelevant anachronism. John Major promised a classless society by the end of the 1990s, Tony Blair said that the old establishment was being replaced by a new, larger, more meritocratic middle class, Gordon Brown vowed to create a generation that would build a Britain where the ‘talent you had mattered more than the title you held’. But for all the pronouncements from various different governments, the country is obsessed as much as ever about class. When the chief whip Andrew Mitchell reportedly hurled abuse at a Downing Street policeman, he was mostly criticised not for his appalling manners, but for his alleged use of the word ‘pleb’, confirming in the eyes of the critics of the Government such as Polly Toynbee that ‘the social class of Cameron’s crew … rule for their own ruling class’.1

A whole host of activities and institutions are attacked for being ‘too middle class’ – the Church of England, English Heritage, Girl Guides, tennis, BBC sitcoms, the Labour party. Various broadcasters, the Chelsea Flower Show, the Royal Opera House and the entire cabinet are derided for being ‘too posh’; rows over the education system are almost entirely centred around how to ensure more working-class children get better grades and places at university; hands are wrung about how nearly every Bafta winner and top-40 musician went to private school, and why a disproportionate number of white working-class boys end up out of work, out of a job, out of luck.

It’s not just the press which casts so much of what they write about in the molten, malleable language of class – ‘Are your neighbours middle-class cocaine addicts like me?’2 is a recent headline in the Daily Mail. Policy makers too increasingly see class as the cause of so many of Britain’s economic and social woes. The Office for National Statistics, and a dazzling array of think-tanks and research houses, publish almost weekly data to show that social inequality continues to widen in Britain – your health, your wealth, your happiness are all related to the social class you belong to. An astonishing amount of time and money is spent measuring and defining the socio-economic groups that make up modern Britain: C1, D, Class 1, managerial, semi-routine sales occupation, intermediate clerical. These groups are meant to be as objective and statistically robust as possible. And all serve to help the Government and its agencies attempt to improve ‘social mobility’ – the ultimate goal of so many in charge.

But the dry statistics relating to the upper deciles, the long-term economically inactive, the ‘discouraged’ and higher managerial classifications are not a true reflection of class in Britain today. Class has never been simply about whether you were rich or poor, whether you were the boss or the worker, or if you paid for your education or not. It was more than that. Class was always a subjective, loaded term, one that implied judgement. It used to be about a thousand little rules designed to trip up those not in the inner circle – what time you ate your evening meal, phoning for the fish knives, how you pronounced Cholmondeley and Featherstonehaugh Ukridge, which day to wear an old school tie. Much of it was knowledge, wrapped up in a secret language and accent, and was a way that social superiors knew to assert their superiority. It was tricky (though not impossible) to fake, and it was designed, so it seemed to those not in the inner circle, to keep outsiders in their place. When Brian Winterflood started a job at the London Stock Exchange in 1951 he wore brown shoes to work, only to be greeted on his first day with shouts, running around the exchange, of ‘Brown boots, brown boots!’ He quickly scuttled off to find a pair of black shoes. ‘And I’ve always worn black ever since.’ Hardly anyone remembers these rules now. Brown shoes are a common sight in the City, while accents have become blurred, with the public school drawl edging ever closer to the Essex twang. Even Prince Harry’s speech is peppered with glottal stops.

Class has changed, as Britain has changed, and its populace has been faced with an ever wider array of choices. Class used to be about your position in life; now it appears to be increasingly about lifestyle. This is a term that only took hold in the 1950s when there started to be enough money around to furnish a lifestyle with more than a scuttle of coal and a week’s holiday in a boarding house at Blackpool. And it took off in the 1960s with the glossy Sunday newspaper magazines that chronicled the swinging consumerism of the era.

This book is an attempt to map some of those changes and to find out what class means in Britain today. It is about the habits and lifestyles of millions of households and families who grew up on salad cream and ended up using balsamic glaze from Morrisons on their monkfish fillets. Of how holidays hop picking in Kent turned into flights to Disney World and cruises around the Canaries, and how tables bought on tick from the Co-op became adorned with Jo Malone smelly candles and an orchid from M&S.

This makes no claim to being a history book, but it does have a nominal starting point: 1954, a year of British triumph, when the first sub-four-minute mile was run, the year after Everest had been conquered and the structure of DNA established, the early years of the new Elizabethan era when it seemed after two decades of deprivation and war that anything was possible. Importantly, for millions of households, 1954 was the year when meat rationing was lifted, the last of the restrictions to be scrapped and an end to 14 years of continually having to check your pocket book before you calculated what you could buy. Families finally had the freedom to spend their weekly pay packet as they saw fit. It kick-started six decades of conspicuous consumption, which have culminated in people scanning their iPhones for Wagamama discount vouchers and supermarket delivery vans ferrying jars of anchovies and espresso pods at ten o’clock at night around the streets of Britain. An era which now looks under threat from the dramatic and almost unprecedented collapse in disposable income for many families – a phenomenon that did not happen in such a sustained way during the recessions of the 1950s, 60s, 70s, 80s and 90s.

It has been six decades of radical change. 1954 also saw the first purpose-built comprehensive school, an attempt to give equal opportunities to the children of Britain, regardless of where or to whom they were born; the release of Bill Haley’s ‘Rock around the Clock’, the first cultural event to give a voice to teenagers; the very first Wimpy bar, bringing the concept of ‘jet-age eating’ to the masses; and the first package holidays to Benidorm, giving ordinary workers a taste of the sun-kissed beaches that only their betters had enjoyed a generation before.

During this second Elizabethan era there have been plenty of seismic changes and many things that have not really moved on at all. Class manages to straddle both camps. In the last 60 years there has been the almost complete destruction of the upper classes, the substantial dismantling of the working classes and the enormous, remorseless rise of the middle classes.

The landed aristocracy who owned Britain and ruled Britain have, save for a few notable exceptions, been forced to either sell off or open up their family homes to the public and vacate their comfortable benches in the House of Lords. Meanwhile, millions of manual workers who were paid decently for a hard day’s work have ended up jobless or in call centres, while the unions and working men’s clubs, organisations that gave so many working communities their backbone, appear to be in terminal decline.

The population of Britain has not got smaller; far from it. Those at the top and the bottom have not disappeared – they have merely moved class. Millions have left the ranks of the working classes and joined the ranks of the middle classes, while hundreds of thousands of those at the top have taken a step down. In the mid-1950s various surveys suggested that about a quarter of the population considered themselves ‘middle class’; that figure now is consistently 70 per cent. The rest say they are working class. No one openly admits to being upper class.

But even if seven in ten people are middle class, that does not mean they all share the same lifestyle. There has certainly been some blurring of once strict boundaries of taste and consumption patterns. The majority of people own their own homes, and some of those a place in the sun too. Even more own a car. Prime ministers wear trainers, royal princesses pop into Topshop to buy skirts, sushi is so commonplace that commuters can pick it up with their pint of milk at the station, and Iceland can sell you frozen chicken Kievs. Sky satellite dishes, formerly a sign of ‘council house culture’, are now found on the side of Belgravia maisonettes. What was once recherché is now quotidian, products and decorations that used to be strictly for the working class are now symbols of distinction. Politicians rush to Greggs to scoff sausage rolls and pasties in an attempt to prove how ‘in touch’ they are with ‘ordinary’ voters, while chipped and rough kitchen utensils that their grandparents would have been thrilled to have thrown out are now snapped up by their wealthier descendants as ‘vintage’.

Despite the severe recession, most of us enjoy a lifestyle of what seems – in comparison with 1954 – unbridled luxury: flights to Thailand, 47-inch televisions, food blenders, bread makers, steak on sale at the local supermarket (open till 10 o’clock at night), fashions that can be replenished every season, olives served alongside chilled chardonnay at your local pub. We are, in consumption terms, nearly all middle class. The white-goods revolution that started under Harold Macmillan, along with the white heat one under another Harold, not only put gadgets into consumers’ hands, it freed millions of women from the drudgery of housework, allowing them to join the ranks of the salariat. Washing machines, freezers and microwaves replaced domestic servants, and in so doing played their part both in creating two-income households and, in turn, a society with enough disposable income for status-defining trips to Itsu and days out at Blenheim Palace, where they can buy the ‘Below Stairs’ range of House Maid’s scrubbing brushes and Butler’s champagne openers.

Even as early as 1960 David Marquand, the academic and future Labour MP, declared that – superficially at least – ‘the class war appears to be over, its warriors drowned in a sea of consumer durables. The working class itself is rapidly adopting middle-class standards, middle-class values and a middle-class style of life. Marks and Spencer dress every shopgirl like a débutante, hire purchase equips working-class kitchens with gadgets which would once have made the middle classes gasp with envy; night after night telly erodes what cultural barriers still remain to divide one class from another. These changes may disconcert the intellectual and appal the nostalgic, but the onward rush of modern industry continues undismayed, slowly transforming the most class-conscious country in the world into “one nation”.’3

But 50 years on, new gulfs have opened up within that ‘one nation’ of shoppers. Do you buy your meat wrapped in waxed paper from a farmers’ market, from Tesco or from Asda? Is your holiday a trip to Butlins in Bognor or via Ryanair to Rimini? Is your electrical gadget a Roberts Radio from John Lewis or a James Martin spice grinder from Argos? These may seem trivialities that can only concern a society corrupted by consumerism. But they matter to an awful lot of people – even if they don’t realise it. One of the women I interviewed for this book, Hayleigh, a mother of three who was brought up in a council house, is accused by her grandmother of ‘shooting above her station’ because she owns a Sainsbury’s hessian bag-for-life. ‘She says I’ve forgotten where I came from.’ Hayleigh uses that same bag-for-life if she should ever pop to Iceland to buy her food – too embarrassed to be seen carrying Iceland plastic carrier bags.

Snobbism was never confined to ducal palaces, and certainly didn’t die out when the Queen stopped débutantes (‘debs’) being presented at court in 1958. It is a powerful social force and has a major influence on how we spend our money. This, particularly in an era when there is less cash about, is now more important, when it comes to deciding status, than how we earn that money, I argue. If everyone around you professes to be of the same class, or even classless, then the battle to assert one’s position comes down to what you consume rather than what you produce. It is about the little things – where you buy your jeans, the thickness of froth on your coffee, the thinness of your bresaola. The food, the clothes, the holidays, the homes, the culture, the furnishings we choose to spend our money on – even the plastic sacks we choose to carry those purchases around in.

This book tries to decipher all these products and work out what they say about us. Spending is more than just a frivolous matter of bags and burgers. It is, for some, a cause of great social anxiety as well as financial hardship and starts when they are in the womb – whether they were born in a private hospital or not, and whether their parents paid for a classified to announce their birth in the pages of a broadsheet newspaper or bought a Burberry sleepsuit and a Juicy Couture buggy to welcome them into the world.

I am aware that a book on class, which ignores the old pillars of social status – family, education, work – is one that only tells half the story, so I have attempted to tackle these topics as well, though even here, I argue, consumption plays a significant part in determining status. There are not many children that made it to Oxford whose parents never spent a penny on a tutor, music class or educational trip out.

It is all these consumer decisions that help separate the ‘middle classes’ that somehow include the Duchess of Cambridge – in her Le Chameau green wellies, Zara tops and Boden skirts – from the ‘middle classes’ that include Asda Mums, living off tinned food just before pay day. With a dazzlingly varied array of shops, brands and products available to furnish our lifestyles, there are many different types of middle class. This book attempts to categorise these different middle classes along patterns of consumption and explain why some brands remain exclusive and desired and others succumb to ‘prole drift’, why Iceland is despised by so many while Aldi is worshipped, why holidaying in Norfolk in a tent is so much more high class than in a hotel in Florida. For ease of reference I have given all these groups labels, many of them a bit flippant. Despite the stereotypes, we are not as a nation easily split into discrete groups, and I realise many of the labels are far from perfect.

There are the Portland Privateers, high earners and high spenders, who stamp their status (often newly won) onto their children before they have even been born by booking into the private maternity unit, preferably the Portland Hospital in London. They are some of the key supporters of a number of successful high-end, high-visibility brands that have flourished even in the economic downturn: Mulberry, Belstaff, Smythson. To the untrained eye they may appear similar to the Rockabillies. This lot is a broad church of consumers, but they have very much a rural attitude to life, even if they live in Fulham rather than Fairford. They are often wealthy individuals, sometimes not at all, whose defining feature is holidaying at home, ideally at the resort of Rock in Cornwall, where they can mingle with fellow Prosecco-sipping holidaymakers in their Jack Wills hoodies and Boden swimming trunks, red trousers, whipping up a Jamie Oliver recipe on the barbecue.

Similar in attitude to the Portland Privateers, but a million miles away from them in terms of income, are the Hyphen-Leighs – acutely aware of the power of brands and labels and keen to assert their status through spending. Their ability to latch onto the latest fashions and make them their own stretches even to the naming of their children – invariably double barrelled and unusually spelt. Paul’s Boutique and Sports Direct are their natural high street habitats, places where smart casual takes on a whole new meaning.

Sun Skittlers couldn’t really give two hoots about whether their polo shirt has a penguin in a top hat, a crocodile, a polo player or a hippo in a bath on the front. Money is spent on leisure, not fashion – from a 40p copy of the Sun to a game of skittles down at their local working men’s club. None of them defines themselves as middle class, but they are fully paid up members of the modern consumer class who despite fairly low incomes are usually home owners, sun seekers and season ticket holders.

The Middleton classes, named in honour of Carole, rather than Catherine, started off life in almost an identical situation to the Sun Skittlers, but have spent many of their waking hours escaping from their red-top, blue-collar, hire-purchase background. They too embraced all the opportunities that consumer Britain threw at them but they wanted more; and trips to Torremolinos were upgraded to Tuscany, the Daily Herald was swapped for the Daily Mail, the Co-op meat counter for M&S ready meals. This does not make them traitors to their roots; they are the golden generation that helped drive post-war Britain out of austerity and are proud to declare themselves ‘middle class’.

Asda Mums, mostly on low incomes, shy away from defining themselves as middle class. But their subtle understanding of status and brands, their insistence that their babies are given organic Ella’s Kitchen mango pouches (while the older one gets a McDonald’s as a treat), their championing of Pampers and Thorpe Park, prove that so much of modern consumption is driven by parents buying for their children. No more so than with this group.

Then there are the Wood Burning Stovers, the descendants of the original Habitat-shopping generation. A well-turned garlic press and a wood-burning stove, rather than an electric whisk and a large TV, is what gives them pleasure – you can spot them with their Daunt book bags tripping their way to pick up a box of yellow courgettes from their farmers’ market in their Birkenstock sandals, trying not to look too smug.

These groups are introduced throughout the book, and will I hope shed a little light on the country we are. Of course many people straddle more than one group and throughout their life have travelled through different classes. I am already on about my third class, having strived to squash my pheasant-plucking background ever since I was at school. I now fall mostly within the Wood Burning Stover category, which is not something I feel particularly comfortable with. No one likes to be pigeon-holed; we all understandably believe that our consumption patterns are unique. But, as the book explains, the consumer companies that supply us with our food, drink, leisure and clothes spend a considerable amount of time categorising us. We might as well try to beat them at their own game.