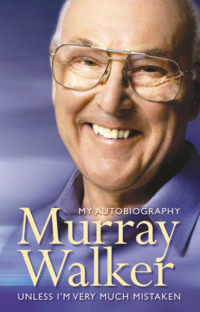

Murray Walker: Unless I’m Very Much Mistaken

In 1925 the Walker family moved to Wolverhampton, for my father had been made an offer he couldn’t refuse – to become Competitions Manager for Sunbeam, ‘the Rolls-Royce of motor cycles’ as the company modestly described itself. More success led to another move in 1928, this time to Coventry and Rudge-Whitworth, which has long since disappeared but was then one of the world’s truly great motor-cycle manufacturers – at a time when motor bikes were a highly desirable everyday means of personal transport for normal people, as opposed to a sporting device for enthusiasts. And that was where my father really came good. Rudge, Norton and the rest of Britain’s motor-cycle manufacturers who dominated the world were in a head-to-head battle for sales. The promotional benefits, both at home and overseas, that came from sporting supremacy were immense, so racing success was vital. At Rudge-Whitworth my father was Sales and Competition Director and he got down to it with a will.

In 1928 he came within an ace of winning what was then by far the most important race in the world, the Senior TT, retiring in the lead with only 14 of the 268 miles to go after a titanic scrap with the great Charlie Dodson. Just two months later he got his revenge by becoming the first man to win a motor cycle Grand Prix at an average speed of over 80mph. It was the Ulster Grand Prix and this time he beat Charlie, after an even more epic duel, by 11 seconds in a race where they were wheel-to-wheel for over two and a half hours. And this on the bumpy, gruelling Clady Circuit riding a bike with no rear suspension, almost solid girder forks, hand-operated gear change and skimpy, narrow, bone-hard tyres. No disrespect to the modern superstars but they made them tough in those days.

With the sales office in London and the factory in Coventry my father had constantly to commute from one to the other by way of the A5 in his mighty 4.5 litre Lagonda, with its mammoth Lucas P 100 headlamps which used to impress young Murray so much. It was a stunning motor car. So he said to my mother, ‘We can live in the Midlands or in the northern part of London. I don’t mind, so it’s your choice.’ Well, that was no contest for my mother who, as a Bedfordshire-born country girl, detested the industrial Midlands where her son had been born and in which he subsequently lived, worked and thoroughly enjoyed himself.

Off we went then to Enfield in Middlesex, which is where I spent most of my time from the age of five until I married at the ripe old age of 36.

Father raced on for Rudge on bikes whose constant development by the brilliant chief designer George Hack had made them the class of the field. He rode to victory in the Isle of Man in 1931, and received an impressive 15 silver TT Trophy Replicas, which I still proudly have. In 1931, Hack masterminded a new 350cc which had never even turned a wheel until it got to the Isle of Man, but the three works entries finished first, second and third with all three team members, my father, Ernie Nott and Tyrrell Smith, breaking the race and lap records. Mighty days! And that’s not to mention umpteen Continental Grand Prix wins. Had there been World Championships in those days, my father would undoubtedly have won at least one of them.

In the meantime I grew up. If my mother had an idyllic youth then I most certainly did. A governess at home started my early education, which was followed by a couple of prep schools in the country before I went to my father’s old public school at Highgate to be taught by several of the masters who had taught my Dad. One of them was the Reverend K R G Hunt, whose claim to fame was that he had played soccer for England as an amateur. On one occasion he got me out in front of the class to beat me (as they did in those days) for something trivial like putting sticky seccotine on the board rubber.

‘I’m going to give you three strokes, Walker, but before I administer justice have you got anything to say in mitigation?’

‘Yes, Sir! I thought you’d be interested to know that I will be the second generation of Walkers you have beaten because you beat my father.’

‘Oh did I? Well, I’m now going to give you six for that!’

Which taught me not to be cocky and to keep my mouth shut in difficult circumstances.

I really enjoyed school. I was no great scholar, but a steady grafter; I got School Certificate with Credits (the equivalent of A-levels today) including, believe it or not, a Distinction in Divinity. I needed an extra subject to compensate for my incompetence at Maths and taught myself by learning almost by heart the Acts of the Apostles and the Gospel according to St Matthew.

Within two years of my arrival at Highgate I’d learnt to play the bugle in the School Corps, become a Prefect, mastered the intricacies of the intriguing wall game Fives, proudly won my First Class shot (0.303 Short Model Lee-Enfield World War One rifles with a kick like a mule) and demonstrated a staggering lack of ability at soccer and cricket due to an abysmal lack of hand and eye co-ordination. Then came the ‘Phoney War’ and with it evacuation to Westward Ho! in glorious North Devon, as the School’s governors were convinced that there was going to be a war and that London would be heavily bombed. They were right on both counts but a year early, so we soon returned. In 1939 we were back in Devon again, this time for the duration, and I was there until 1941.

What a life it was! My school house was at the end of a superb beach with the Atlantic breakers crashing ashore just beneath my dormitory window. Hardly affected by the rationing to which the rest of Britain was subjected, it was shorts and shirts the whole year round, weekend cycle rides to Clovelly and Appledore, excitedly staring up at the Avro Ansons of Coastal Command as they lumbered across the blue skies in search of U-boats, swimming in the sea, sunbathing on the Pebble Ridge and the joy of achieving things that mattered to me as I developed. I rose to the giddy height of Company Sergeant Major of the School Corps, pompously marching about shouting commands in my World War One khaki uniform, complete with knee-length breeches, puttees, peak cap, scarlet sash and a giant banana-yellow drill stick with a silver knob on the top. I became Captain of Shooting with the honour of an annual competition at Bisley and even, arrogance of arrogance, an instructor to members of the LDV (Local Defence Volunteers: the predecessor of the Home Guard, or ‘Dad’s Army’), many of whom had fought in World War One, teaching them how to use a Lewis machine gun. And I loved it.

But then, at 18, and with school behind me, it was time to go to war myself. As Britain unflinchingly suffered the devastating ravages of Hitler’s Messerschmitt, Dornier and Junkers bombers, while his seemingly invincible armies raced across Russia, it was also slowly starting to ready itself for the invasion of Europe. My country needed me. Youth does not heed the horrors of war and I was eager to go – but in one particular direction. Conscription was very much in force and if you waited to be called you went where they sent you. However, if you volunteered and were accepted you went where you wanted to. I had stars in my eyes and knowing that inadequate eyesight prevented me from going for every schoolboy’s dream – fighter pilot – I volunteered for tanks. I was accepted all right but, believe it or not, they said, ‘Sorry Murray, you’ve got to wait. Not enough of the right sort of kit for you to train on. So off you go. Fill in the time and we’ll let you know when we’re ready.’

What a frustrating setback. It is difficult to convey to today’s generation, who are lucky not to have experienced it, how totally involved, intense and patriotically passionate everyone in Britain was about the war. Germany, and everything to do with it, was then regarded as the personification of evil. It is easy now, divorced from the bitter loathing and hatred that war inevitably generates, to accept that the vast majority of its people were (and are) the same as us but there was naturally little appreciation and no tolerance then of the fact that the ordinary Germans had been taken over by an obsessive megalomaniac and the fanatical political machine he had created. Hitler and his minions were doing unspeakably terrible things in the name of the Third Reich and were aiming for world domination. With the enemy literally at the door, Britain had its back to the wall and was fighting for its very survival. There was a gigantic amount to be done and I desperately wanted to be a part of it. I still had a bit of a wait ahead of me though.

‘Fill in the time,’ they had said. But how? It clearly wasn’t going to be long before I was in battledress but, as I have so often been, I was lucky.

At that time the Dunlop Rubber Company, then one of Britain’s greatest companies, awarded 12 scholarships a year to what they regarded as worthy recipients and I was fortunate to win one of them. Sadly, Dunlop now exists only as a brand name, having been fragmented and taken over by other companies including the Japanese Sumitomo organization whose country it did so much to defeat in the war. But back then Dunlop, with its proud boast ‘As British as the Flag’, was a force in the world of industry with many thousands of employees all over the world. It owned vast rubber plantations and produced, distributed and sold tyres, footwear, clothing, sports goods, cotton and industrial products and Dunlopillo latex foam cushioning.

Its scholarship students were based at its famous Fort Dunlop headquarters (part of which still exists beside the M6 in Birmingham) and had tuition and fieldwork on all of its activities as well as instruction from top people on every aspect of what makes a business tick, from production and distribution to marketing, law and accountancy. It was an invaluable grounding. I had a whale of a time, living in digs at 58 Holly Lane, Erdington with the Bellamy family, spreading my wings and discovering, amongst other things and to my surprise and delight, that girls had all sorts of charms I hadn’t experienced at Highgate.

But then came the call via a telegram. ‘We’re ready for you now, Murray. Report to the 30th Primary Training Wing at Bovington, Dorset on 1 October 1942’. I went there as a boy and rather more than four years later was demobbed at Hull as a man.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов