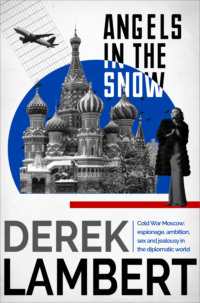

Angels in the Snow

He collected his mail and took the lift up to his floor. The duty marine who had recently arrived from Vietnam greeted him with a deference tinged somehow with the contempt he felt a military man should feel towards a diplomat. A closed-circuit television set recording departures and arrivals outside flickered beside him.

‘Seen anyone suspicious on that thing today?’ Randall asked.

The marine, crew-cut and built like a Wimbledon champion, shook his head. ‘Seen one helluva lot of snow, Mr. Randall,’ he said.

‘Should be a change after Vietnam.’

The marine shrugged. ‘I guess it’s a change right enough.’

‘But not a change for the better?’

The marine grimaced. What had he done to deserve Moscow?

In his office the secretary he shared with another diplomat was dealing his letters on to his desk.

‘You look like a card sharper,’ he said.

‘No card sharper should have fingers as cold as mine,’ she said.

Her fingers, he reflected, looked cold even in the summer. Thin and chalky like a school teacher’s fingers. Elaine Marchmont finished the deal and sat down at her desk. She was wearing her boots for the first time since the last winter had melted and dried up.

‘Shouldn’t you take those things off in the office?’ he asked.

‘Is it against protocol to wear boots in the office?’

‘Not as far as I know. I didn’t think they looked too comfortable, that’s all.’

‘If it was someone like Joyce Holiday or … or Mrs. Fry wearing them you’d tell them to keep them on.’

‘Why Mrs. Fry?’ he asked. And added quickly: ‘Or why Miss Holiday for that matter?’ He hoped Janice Fry had left his flat by now.

‘Because they’re the sort of women men like to see in boots.’

‘I don’t give a damn about boots on anyone. Those happened to look uncomfortable. You didn’t steal them from a Russian soldier did you? I noticed one on guard outside the Kremlin without his boots on.’

Elaine Marchmont said: ‘Why do you have to keep riling me? We can’t all be sex kittens.’

Then he felt sorry for her. Sorry about the boots that did nothing for her. Sorry about her myopia, her thin body, her hair which was the colour of dried grass rather than straw.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said.

‘There’s some decoded cables for you,’ she said. ‘Some mail from the pouch. A report from Chambers in agriculture. Three invitations to cocktail parties and APN’S translations of the Soviet Press.’

There was a duty letter from his wife, written with effort, recording the boys’ progress at school, asking for money to redecorate the flat in Washington. The words only flowed naturally when briefly they were oiled by anger, and she recalled his infidelity. The words became her voice, precise and plaintive and Anglicised. ‘Who, I wonder, is the current girl friend.’ Then she remembered her Bostonian upbringing; the voice faded and she hoped without sincerity that he was keeping well.

The cables contained Washington reaction to Soviet reaction to American policy in Vietnam. Their phraseology was as drearily predictable as the wording of a protest note.

Cocktails with his neighbours who still included his wife on the invitation although they knew she had left. Cocktails with his opposite number at the British Embassy. Cocktails with his own ambassador. Gallons of cocktails, except that there were never any cocktails—Scotch and soda, gin and tonic, occasionally Russian champagne.

Snowflakes pressed against the window and peeped in before dissolving. He walked to the window and gazed down at Tchaikovsky Street. A few parchment leaves adhered to the branches of the trees, clinging hopelessly to summer. Fur hats and head-scarves bobbed and weaved among each other and an ambulance, not much bigger than a limousine, raced towards Kutuzovsky Prospect where he lived.

‘The first road accident of the winter,’ he said.

‘And I’m willing to bet a cab was involved,’ said Elaine Marchmont. ‘The cab drivers are pigs. Worse than the French.’

‘Cab drivers are the same the world over. Except in Lagos. There’s nothing quite as bad as a Lagos cab driver.’

Elaine Marchmont knew nothing of Lagos cab drivers. ‘These pigs won’t even stop for you,’ she said. ‘And when they do they’re as surly as hell.’ She ground out half a cigarette. ‘I hate them,’ she said.

Randall looked at her speculatively. ‘Elaine,’ he said, ‘how long have you been here?’

‘Eighteen months. Going on nineteen. Why?’

‘Isn’t it about time you took a vacation?’

‘Moscow,’ she said firmly, ‘is not getting me down. Not one little bit.’

‘You must be unique,’ Randall said.

‘You know I like it.’

‘Sure,’ Randall said. ‘It’s an experience. Isn’t that right?’

‘I’ve enjoyed every minute of it.’

‘Come on,’ Randall said. ‘Not every minute. What about those minutes when you were trying to get a cab?’

‘And I’m pretty sick of hearing people bitching about Moscow. They should never have joined the diplomatic service.’

‘Moscow gets you,’ Randall said, ‘whether you like it or not. I know of one guy who lasted six days. They had to hold a plane at Sheremetievo to ship him out. He reckoned everyone was after him.’

Elaine Marchmont smiled wanly. ‘At least,’ she said, ‘I know no one is after me.’

‘Come on,’ Randall said. There wasn’t much else to say. Every embassy had its spinsters who volunteered for Moscow in the belief that there would be a surfeit of bachelors. But most of the men were married and the bachelors were careerists unlikely to jeopardise their careers by serious affairs within their embassies. And in any case they could always take the nannies out.

‘You’re a lousy diplomat,’ Elaine Marchmont said. ‘You know it’s true. I remind myself of an actress who used to play the perfect secretary on the movies. Eve someone or other. She used to cover up her lack of sex appeal by making cracks about it and helping her boss with his love affairs while all the time she was in love with him.’

‘Are you in love with me?’ Randall asked.

‘You must be joking,’ said Elaine Marchmont.

‘It’s stopped snowing,’ he said.

‘Sure. And now it’ll melt and there will be fogs and the planes won’t come in and we won’t get any mail.’

‘You sound as if you know your Russian winter off by heart. This is the thing that gets most people. The thought of another winter.’

‘I’ll survive. I don’t mind the real winter. It’s the preliminaries that bug me.’

‘Don’t use that word,’ Randall said. ‘This guy they flew out after six days thought everywhere was bugged.’

‘The preliminaries and the aftermath,’ she went on. ‘The snow that keeps stopping and starting. The mists. And then in April the mud and slush and running water. The whole place sounds like a running cistern.’

Her face was pale and taut, summer freckles on her nose already fading. Everything about her was pale, even her voice.

‘I honestly think you ought to take a holiday,’ he said. ‘Prepare yourself for the winter.’

‘And where should I go? Helsinki—again? I might as well stay here.’

You could fly to Copenhagen,’ Randall said. ‘Or Stockholm. Or London even.’

‘Or Siberia,’ Elaine Marchmont said. ‘I’ve never been there. You seem to forget a vacation costs a lot of dollars which I don’t happen to have.’ She blew her nose. ‘It’s the thought of Christmas that really frightens me.’

Christmas. Children around a tree fragile with bright glass. The elation subsided. Tonight a cocktail party.

‘Nonsense,’ he said. ‘You’ll have a great Christmas.’

‘Sure,’ she said. ‘With other people’s children. Buying them lousy Russian toys and helping other women cook the turkey. I just can’t wait.’

‘I think I’ll take a coffee break,’ he said.

The canteen was a small, gloomy place adjoining the transport section. A young German called Hans who had a way with hamburgers and tossed salad was in charge. He was sleekly blond, taciturn and efficient and gave the impression that he had exactly calculated the savings needed to return to The Fatherland to open his own restaurant. In Dusseldorf, perhaps, where a lot of money was spent on schnitzel and steaks and schnapps.

Here crew-cut young Kremlinologists discussed nuances of Soviet policy and reached conclusions which would have astonished the instigators. And when they had decided Soviet intentions in Vietnam, China, the Middle East and Africa they discussed the new ambassador and his wife, gently probing each other’s opinions in case they were in the presence of a confidant of the ambassador. They discussed the winter gathering around them; and they luxuriated in the privations and frustrations of life in Moscow—but only if they were friends because it was easy to become known as someone who was for ever bitching. If they were really close they debated the possibility of love affairs on the embassy circuit in Moscow and, if they were even closer, they confided their own desires.

Here American journalists dropped in for a snack with their hungry, pregnant wives. If there were rivals present they managed through faint praise to deride their exclusive stories; or to hint at their own mysterious assignments with anonymous Russian contacts. Journalists and diplomats mixed warily over hamburgers and salad, canned beer and ginger beer, seeking each other’s knowledge with deference and undertones of contempt for each other’s profession.

Randall took his coffee and joined the correspondents of a magazine and a news agency, who were talking shop while their wives, both as taut-bellied as bass drums, talked about babies, nannies and Russian maids.

They greeted him eagerly. No correspondent had really understood his brief within the embassy. He was a deep one, a dark one, with unfathomed depths of information to be tapped. Or he was a clerical nonentity whose non-slip mask concealed nothing. At cocktail parties each correspondent had stiffened Randall’s whiskies to free the mask; both had failed. Each was valuable to Randall because, with their contacts within the freemasonry of journalism, they gathered a little information from the correspondents of other countries; and sometimes, but very rarely, from Russians.

‘How’s the brains department these days?’ said the agency man. He had no idea what Randall’s job was.

‘Fine,’ Randall said. ‘Just fine.’

The agency man’s wife said: ‘I’m darned sure my maid has been stealing my cigarettes.’ In Cleveland, Randall thought, she would have been lucky to have had a cleaning woman in twice a week.

Everyone made plump jokes about pregnancy. Both women, terrified of Russian midwifery, were taking the train to Helsinki to have their babies.

‘The trouble with Russia where abortion is legal is they might think I’ve gone in to have one,’ said the magazine man’s wife.

‘I guess they would think you were a little on the tardy side,’ Randall said. Everyone laughed. That was one of the assets of being mysterious: everyone laughed at your jokes. ‘What are the agencies putting out today?’ he asked.

‘I don’t know about THE agencies. We haven’t moved a thing except the Pravda stuff on Vietnam and the Chinese. I sometimes wonder who they hate most—the Chinks or us.’

‘They don’t hate either,’ Randall said. ‘It’s just propaganda Soviet style.’

‘It’s so awful,’ said the magazine man’s wife. ‘This slaughter in Vietnam. Those terrible pictures of mutilated babies.’

The men regarded her uneasily. She had been emotional lately what with the baby coming and Moscow in general.

Behind them Hans moved stealthily from hamburger to steak.

‘It makes me want to cry,’ she said.

‘There, there, honey,’ said her husband. ‘You just take yourself to Finland soon and have that son for us.’

‘Sure I’ll have your son,’ said his wife. ‘Just so that he can go to Vietnam and be killed.’

‘That’s a long time ahead,’ said her husband.

‘Sure it’s a long time,’ she said. ‘I just wonder what little old battlefield they’ll have fixed up for him by then.’

The agency man’s wife said: ‘It could be a daughter.’

And Randall, bored by the dramatisation of the unborn, said: ‘Let’s worry about the weather. It’s the only thing we know for sure. It’s going to be very cold very soon.’

‘I don’t think I could stand another full winter,’ the agency man’s wife said.

‘We’re moving off,’ her husband explained.

‘Where to?’ Randall asked politely.

‘Paris, I guess. I’ve done a Vietnam stint.’

Vietnam coloured everything if you were an American, Randall thought. Especially in Russia. Every day the Press attacked American policy with fierce words which had been de-gutted by repetition: instead of crusading the newspapers nagged. But nagging eroded the questioning spirit. ‘Bandit aggression … dirty war.’ The phrases stuck and were assimilated like repetitive advertising. Student demonstrators automatically daubed their banners with these words. They had become a habit.

The counsellor for cultural affairs who looked as if he might have been a prize-fighter walked in and went through a pantomime of being cold. Shivering, rubbing his hands, calling for hot, very hot, coffee. Randall wondered why he still wore a lightweight suit. A first secretary who dealt with Press queries looked round the door, noticed the Pressmen present and hesitated. But the correspondents spotted him and waved; he was trapped.

Two girl secretaries with sallow complexions drank milk and talked intensely. Randall guessed they were discussing their careers or last night’s Bolshoi. ‘So virile … a real man … imagine him leaping into your bedroom.’ It was the Bolshoi.

‘When is your wife coming back?’ the magazine man’s wife asked.

You bitch, he thought. ‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘I had a letter from her just this morning. She’s not quite up to it yet.’

‘Poor girl. I sympathise with her. It’s too darned easy to crack up in this place.’

‘She didn’t exactly crack up,’ Randall said. ‘She would have stayed on if it hadn’t been for the kids. But we had to get them to a decent school. They were growing up too fast.’

The agency man’s wife folded her hands across her big belly. ‘I envy her,’ she said. ‘Oh boy, how I envy her being back in Washington.’

‘You’re free to go any time you like,’ said her husband. ‘You know that.’ There had been a row that morning.

His wife smiled and became pretty again. ‘I know,’ she said. ‘I know that. But you know I couldn’t leave you here. God knows what you’d get up to.’

They clasped hands, pleased that the others saw them happy together.

‘I must go,’ Randall said.

In the transport section the season’s first automobile casualty was limping in, an apple-green Chev with a buckled fender.

‘What happened?’ Randall asked.

The driver, one of the military attachés, said: ‘A —ing taxi.’

The sky had lightened again and the snow on the ground was fading. But you could feel winter assembling around the city; converging from the Arctic, from Siberia; shivering the match-stick forests of larch and birch, crusting the lakes with tissues of ice, breathing into the rheumy old dachas in the villages.

That afternoon, because the anti-freeze had not arrived at the embassy and the Russian anti-freeze tended to freeze, he poured a bottle of vodka in the radiator of his car.

The rear entrances of the diplomatic block—there were no front entrances—reminded Randall of a set from West Side Story. There was, like Russian diplomacy, very little diplomatic about them.

The tall flats, made of pale, dirty brick, almost surrounded the big car park and ramshackle playground. Balconies which few trusted seemed to have been stuck on the walls and were used by pigeons and sparrows and Africans who draped them with laundry. At night you could see television sets flickering and diplomats dining and sometimes the unwary undressing for bed.

On summer nights youths from a dozen countries lounged against the big packing cases in which furniture was shipped in and out. They wore jeans and sneakers and commented on pretty women passing in languages which they hoped were not understood. Little girls, black, coffee and white, played hopscotch around the chalk-scrawled entrances; and on the benches sat mammies and mummies and nannies remembering greasy Accra evenings, the curried dusks of New Delhi, late sunshine on the Serpentine, night thickening and salted by the sea in San Francisco.

The nights were pierced with children’s cries. Adolescent oaths in Spanish, French, Italian and many varieties of English. It was an international ghetto, a Block of Babel.

When Randall arrived the fire engines had just pulled up. An Algerian boy playing with matches inside an empty packing case had set fire to it and the crate was in flames. The boy lay on the dirty sand shivering violently and whimpering; his clothes and hair were scorched and, although his parents were beside him, he kept calling for his baby sister.

Sparks spiralled into the evening fog pressing down over the city. A breeze blew the sparks to one side and flames, like orange liquid, ran down the side of another case dust-dry after the hot late-summer. The case, as big as a small shop, was addressed in black paint to Cairo. A middle-aged woman with a dark creased face moaned, clasped her hands and shook her head.

‘All her furniture’s in there,’ someone shouted.

‘Let’s get it out then.’

‘Can’t, there’s no bloody key.’

‘The key,’ shouted a Swede. ‘You must give us the key.’

The woman began to rock from side to side. ‘My husband,’ she said. ‘My husband.’

Firemen in khaki were running with a hose to a hydrant.

Randall got a crowbar from his car. ‘Come on,’ he said, ‘we’ll bust it open.’ He grabbed the arm of a young man hurrying across the playground towards the fire. It was the Englishman he had collided with that morning. Most of Randall’s mind was occupied with saving the furniture; but a sliver of it observed maliciously that the stranger’s new coat, bright shoes and raw gloves would never be quite the same again.

Randall jammed the crowbar behind the bar of metal held by a padlock and pulled. The Englishman pulled beside him. He felt the bar give a little. Spectators crowded the precarious balconies and children chased the sparks. Then the jet from the hose hit the side of the case thrusting it backwards. Smoke and steam enveloped Randall and the Englishman.

‘Pull,’ Randall shouted. ‘For Christ’s sake pull.’

The bar ripped loose and the doors burst open. Hot white smoke burst out. Other men ran forward and helped them pull the furniture, bandaged in newspaper, out of the case. The cheap veneer was blistered and butterflies of flames fluttered among the newspaper. The woman watched, still rocking, murmuring to herself in Arabic.

‘Poor bitch,’ Randall said. ‘She was going home tomorrow. That’s all she needed.’ He looked at the Englishman and laughed. His eyes were red, his cheeks coursed with sooty streams, his coat singed and flaked with ash. ‘You’d better come up and have a drink,’ he said. ‘You look as if you need one.’

‘No thanks. I’m perfectly all right. I need a bath more than a drink.’

‘A drink first,’ Randall said firmly. ‘Come on. What’s your name by the way?’

‘Mortimer. Richard Mortimer. I only arrived last night.’

‘A baptism of fire,’ Randall said.

Mortimer smiled, teeth flashing coonishly in his blackened face. ‘It’ll be something to write home about,’ he said.

Randall entered the flat cautiously in case Mrs. Fry had returned, or never left. There was a note in the bedroom: that was inevitable. It would have taken over an hour to compose, vituperation distilled into four painstaking paragraphs. He tore it up without reading it. The room smelt faintly of her hair lacquer.

‘What can I get you?’ he asked. Mortimer was patrolling the lounge examining his possessions—the simova, two heavy brass candlesticks, beaming wooden dolls, flabby succulents, a cactus which had sprouted two ears and looked like a cat, a collection of china eggs bought in one of the commission shops, the modern art sprawled across one wall.

Mortimer said he would have a beer. Randall said: ‘You need a Scotch.’ And poured him one. ‘What do you think of them?’ He pointed at the paintings.

‘I think they’re splendid,’ Mortimer said.

‘I think that one looks like two Indian footprints, one on either side of a lavatory pan. My wife bought it. She bought them all.’

‘I take it you don’t like them.’

‘I don’t mind them for what they are. An hour or so’s decorative work. I object to them being described as art.’

‘I don’t much care for modern art myself,’ Mortimer said.

‘Then why didn’t you say so?’

Mortimer tinkled the ice in his glass. ‘Perhaps because I didn’t want to offend you,’ he said. ‘Perhaps because I’m a diplomat. Perhaps because I’ve been taught manners.’

‘Well said. Have another Scotch.’

Outside, as the evening chilled and darkened, an ambulance arrived to take the burned boy away.

‘Poor little devil,’ said Randall. He was thinking of his own boys. ‘I expect he was looking forward to the snow.’

‘Was he badly burned?’

‘I don’t know. Possibly not. I can’t stand seeing children hurt.’

They stood at the window watching the marionettes far below tidying up the drama. On the other side of the playground women were burning refuse on a bonfire. One by one the lights came on in the block across the way.

‘Sometimes,’ Randall said, ‘I feel as if I can control everything from here. See that car moving over there? I’ll park it in that space beside the Mercedes and the Chev.’ Obediently the car turned in. ‘And I’ll lead the driver across the sand, where he will pause briefly to look at the burned-out case, to entrance seven.’ The man followed the instructions.

‘Very impressive,’ Mortimer said.

‘Not really. He always parks there and he lives at number seven. I knew he wouldn’t bother too much with the fire. He’s a Norwegian, not very imaginative.’

‘There’s certainly a lot of nationalities here.’

‘The lot. The East Europeans are in that new block over there. We don’t mix except for cocktails. You’ll be having a lot of cocktails. Are you married?’

‘No. Are you?’

‘In a manner of speaking. My wife is in America.’ He poured himself another drink. ‘We’re separated if you must know,’ he said; and wondered why the green young Englishman was the first person in whom he had confided.

‘I’m sorry. Have you any children?’

‘Two.’ Randall didn’t want to discuss it any more. ‘A diplomat hanged himself here this morning,’ he said.

‘So I heard.’

The stylised understatement irritated Randall. ‘You Goddam Englishmen,’ he said, is that all you can say—so I heard?’

‘It’s terrible. I’m sorry but I’m a bit overwhelmed. The fire, a hanging, my first day in Moscow …’

‘You’ll soon settle down. When the real snow comes. It sort of cossets you the first time round. It’s how you always imagined Russia. Come February and March you never want to see another snowflake. It’s on your second or third winter that you start to crack up.’

‘It is my experience,’ said Mortimer, selecting his words carefully, ‘that wherever you arrive there’s always someone around who wants to frighten you. I don’t believe that it’s such a bad place. It can’t be that bad.’

‘It isn’t,’ Randall said. ‘It’s me. Have another drink.’

‘No thanks. I’ll have to go now. Thanks for your hospitality.’

‘Don’t mention it. Drop in any time.’

He watched the marionette Mortimer, lit by the lamps round the playground, walking towards his entrance. Soiled overcoat flapping, gloves in hand, staring at the ground. Prim and proud and gullible. The affection which Randall felt surprised him. He retained it, examined it and put it aside. And guided Mortimer into his entrance.

Then he tore up the cocktail party invitation and walked around smoking and drinking whisky. The flat seemed more empty than ever before, resonant, washed with restless shadows. The children’s room was now the lumber room. In one corner stood a pile of broken toys. In a drawer of a filing cabinet he found last year’s Christmas cards. One of them was a Russian New Year card from his wife, a gold bust of Lenin on a blue background scattered with stars. ‘A happy Christmas, darling, and a happy New Year.’ But it had all been over even then. And two more Russian cards, bright, beaming dolls linking arms, from the children. There was a film of dust over the cards.