Berlin Game

‘I know just the place, Bernie. Straight up Friedrichstrasse, under the railway bridge at the S-Bahn station and it’s on the left. On the bank of the Spree: Weinrestaurant Ganymed.’

‘Very funny,’ I said. Between us and the Ganymed there was a wall, machine guns, barbed wire, and two battalions of gun-toting bureaucrats. ‘Turn this jalopy round and let’s get out of here.’

He switched on the ignition and started up. ‘I’m happier with her away,’ he said. ‘Who wants to have a woman waiting at home to ask you where you’ve been and why you’re back so late?’

‘You’re right, Werner,’ I said.

‘She’s too young for me. I should never have married her.’ He waited a moment while the heater cleared the glass a little. ‘Try again tomorrow, then?’

‘No further contact, Werner. This was the last try for him. I’m going back to London tomorrow. I’ll be sleeping in my own bed.’

‘Your wife … Fiona. She was nice to me that time when I had to work inside for a couple of months.’

‘I remember that,’ I said. Werner had been thrown out of a window by two East German agents he’d discovered in his apartment. His leg was broken in three places and it took ages for him to recover fully.

‘And you tell Mr Gaunt I remember him. He’s long ago retired, I know, but I suppose you still see him from time to time. You tell him any time he wants another bet on what the Ivans are up to, he calls me up first.’

‘I’ll see him next weekend,’ I said. ‘I’ll tell him that.’

2

‘I thought you must have missed the plane,’ said my wife as she switched on the bedside light. She’d not yet got to sleep; her long hair was hardly disarranged and the frilly nightdress was not rumpled. She’d gone to bed early by the look of it. There was a lighted cigarette on the ashtray. She must have been lying there in the dark, smoking and thinking about her work. On the side table there were thick volumes from the office library and a thin blue Report from the Select Committee on Science and Technology, with notebook and pencil and the necessary supply of Benson & Hedges cigarettes, a considerable number of which were now only butts packed tightly in the big cut-glass ashtray she’d brought from the sitting room. She lived a different sort of life when I was away; now it was like going into a different house and a different bedroom, to a different woman.

‘Some bloody strike at the airport,’ I explained. There was a tumbler containing whisky balanced on the clock-radio. I sipped it; the ice cubes had long since melted to make a warm weak mixture. It was typical of her to prepare a treat so carefully – with linen napkin, stirrer and some cheese straws – and then forget about it.

‘London Airport?’ She noticed her half-smoked cigarette and stubbed it out and waved away the smoke.

‘Where else do they go on strike every day?’ I said irritably.

‘There was nothing about it on the news.’

‘Strikes are not news any more,’ I said. She obviously thought that I had not come directly from the airport, and her failure to commiserate with me over three wasted hours there did not improve my bad temper.

‘Did it go all right?’

‘Werner sends his best wishes. He told me that story about your Uncle Silas betting him fifty marks about the building of the Wall.’

‘Not again,’ said Fiona. ‘Is he ever going to forget that bloody bet?’

‘He likes you,’ I said. ‘He sent his best wishes.’ It wasn’t exactly true, but I wanted her to like him as I did. ‘And his wife has left him.’

‘Poor Werner,’ she said. Fiona was very beautiful, especially when she smiled that sort of smile that women save for men who have lost their woman. ‘Did she go off with another man?’

‘No,’ I said untruthfully. ‘She couldn’t stand Werner’s endless affairs with other women.’

‘Werner!’ said my wife, and laughed. She didn’t believe that Werner had affairs with lots of other women. I wondered how she could guess so correctly. Werner seemed an attractive sort of guy to my masculine eyes. I suppose I will never understand women. The trouble is that they understand me; they understand me too damned well. I took off my coat and put it on a hanger. ‘Don’t put your overcoat in the wardrobe,’ said Fiona. ‘It needs cleaning. I’ll take it in tomorrow.’ As casually as she could, she added, ‘I tried to get you at the Steigerberger Hotel. Then I tried the duty officer at Olympia but no one knew where you were. Billy’s throat was swollen. I thought it might be mumps.’

‘I wasn’t there,’ I said.

‘You asked the office to book you there. You said it’s the best hotel in Berlin. You said I could leave a message there.’

‘I stayed with Werner. He’s got a spare room now that his wife’s gone.’

‘And shared all those women of his?’ said Fiona. She laughed again. ‘Is it all part of a plan to make me jealous?’

I leaned over and kissed her. ‘I’ve missed you, darling. I really have. Is Billy okay?’

‘Billy’s fine. But that damned man at the garage gave me a bill for sixty pounds!’

‘For what?’

‘He’s written it all down. I told him you’d see about it.’

‘But he let you have the car?’

‘I had to collect Billy from school. He knew that before he did the service on it. So I shouted at him and he let me take it.’

‘You’re a wonderful wife,’ I said. I undressed and went into the bathroom to wash and to brush my teeth.

‘And it went well?’ she called.

I looked at myself in the long mirror. It was just as well that I was tall, for I was getting fatter, and that Berlin beer hadn’t helped matters. ‘I did what I was told,’ I said, and finished brushing my teeth.

‘Not you, darling,’ said Fiona. I switched on the Water-Pik and above its chugging sound I heard her add, ‘You never do what you are told, you know that.’

I went back into the bedroom. She’d combed her hair and smoothed the sheet on my side of the bed. She’d put my pyjamas on the pillow. They consisted of a plain red jacket and paisley-printed trousers. ‘Are these mine?’

‘The laundry didn’t come back this week. I phoned them. The driver is ill … so what can you say?’

‘I didn’t check into the Berlin office at all, if that’s what’s eating you,’ I admitted. ‘They’re all young kids in there, don’t know their arse from a hole in the ground. I feel safer with one of the old-timers like Werner.’

‘Suppose something happened? Suppose there was trouble and the duty officer didn’t even know you were in Berlin? Can’t you see how silly it is not to give them some sort of perfunctory call?’

‘I don’t know any of those Olympia Stadion people any more, darling. It’s all changed since Frank Harrington took over. They are youngsters, kids with no field experience and lots and lots of theories from the training school.’

‘But your man turned up?’

‘No.’

‘You spent three days there for nothing?’

‘I suppose I did.’

‘They’ll send you in to get him. You realize that, don’t you?’

I got into bed. ‘Nonsense. They’ll use one of the West Berlin people.’

‘It’s the oldest trick in the book, darling. They send you over there to wait … for all you know, he wasn’t even in contact. Now you’ll go back and report a failed contact and you’ll be the one they send in to get him. My God, Bernie, you are a fool at times.’

I hadn’t looked at it like that, but there was more than a grain of truth in Fiona’s cynical viewpoint. ‘Well, they can find someone else,’ I said angrily. ‘Let one of the local people go over to get him. My face is too well known there.’

‘They’ll say they’re all kids without experience, just what you yourself said.’

‘It’s Brahms Four,’ I told her.

‘Brahms – those network names sound so ridiculous. I liked it better when they had codewords like Trojan, Wellington and Claret.’

The way she said it was annoying. ‘The postwar network names are specially chosen to have no identifiable nationality,’ I said. ‘And the number four man in the Brahms network once saved my life. He’s the one who got me out of Weimar.’

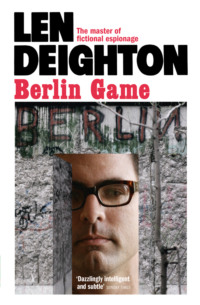

‘He’s the one who is kept so damned secret. Yes, I know. Why do you think they sent you? And now do you see why they are going to make you go in and get him?’ Beside the bed, my photo stared back at me from its silver frame. Bernard Samson, a serious young man with baby face, wavy hair and horn-rimmed glasses looked nothing like the wrinkled old fool I shaved every morning.

‘I was in a spot. He could have kept going. He didn’t have to come back all the way to Weimar.’ I settled into my pillow. ‘How long ago was that – eighteen years, maybe twenty?’

‘Go to sleep,’ said Fiona. ‘I’ll phone the office in the morning and say you are not well. It will give you time to think.’

‘You should see the pile of work on my desk.’

‘I took Billy and Sally to the Greek restaurant for his birthday. The waiters sang happy birthday and cheered him when he blew the candles out. It was sweet of them. I wish you’d been there.’

‘I won’t go. I’ll tell the old man in the morning. I can’t do that kind of thing any more.’

‘And there was a phone call from Mr Moore at the bank. He wants to talk with you. He said there’s no hurry.’

‘And we both know what that means,’ I said. ‘It means phone me back immediately or else!’ I was close to her now and I could smell perfume. Had she put it on just for me, I wondered.

‘Harry Moore isn’t like that. At Christmas we were nearly seven hundred overdrawn, and when we saw him at my sister’s party he said not to worry.’

‘Brahms Four took me to the house of a man named Busch – Karl Busch – who had this empty room in Weimar …’ It was all coming back to me. ‘We stayed there three days and afterwards Karl Busch went back there. They took Busch up to the security barracks in Leipzig. He was never seen again.’

‘You’re senior staff now, darling,’ she said sleepily. ‘You don’t have to go anywhere you don’t want to.’

‘I phoned you last night,’ I said. ‘It was two o’clock in the morning but there was no reply.’

‘I was here, asleep,’ she said. She was awake and alert now. I could tell by the tone of her voice.

‘I let it ring for ages,’ I said. ‘I tried twice. Finally I got the operator to dial it.’

‘Then it must be the damned phone acting up again. I tried to phone here for Nanny yesterday afternoon and there was no reply. I’ll tell the engineers tomorrow.’

3

Richard Cruyer was the German Stations Controller, the man to whom I reported. He was younger than I was by two years and his apologies for this fact gave him opportunities for reminding himself of his fast promotion in a service that was not noted for its fast promotions.

Dicky Cruyer had curly hair and liked to wear open-neck shirts and faded jeans, and be the Wunderkind amongst all the dark suits and Eton ties. But under all the trendy jargon and casual airs, he was the most pompous stuffed shirt in the whole Department.

‘They think it’s a cushy number in here, Bernard,’ he said while stirring his coffee. ‘They don’t realize the way I have the Deputy Controller (Europe) breathing down my neck and endless meetings with every damned committee in the building.’

Even Cruyer’s complaints were contrived to show the world how important he was. But he smiled to let me know how well he endured his troubles. He had his coffee served in a fine Spode china cup and saucer, and he stirred it with a silver spoon. On the mahogany tray there was another Spode cup and saucer, a matching sugar bowl, and a silver creamer fashioned in the shape of a cow. It was a valuable antique – Dicky had told me that many times – and at night it was locked in the secure filing cabinet, together with the log and the current carbons of the mail. ‘They think it’s all lunches at the Mirabelle and a fine with the boss.’

Dicky always said fine rather than brandy or cognac. Fiona told me he’d been saying it ever since he was president of the Oxford University Food and Wine Society as an undergraduate. Dicky’s image as a gourmet was not easy to reconcile with his figure, for he was a thin man, with thin arms, thin legs and thin bony hands and fingers, with one of which he continually touched his thin bloodless lips. It was a nervous gesture, provoked, said some people, by the hostility around him. This was nonsense of course, but I did dislike the little creep, I will admit that.

He sipped his coffee and then tasted it carefully, moving his lips while staring at me as if I might have come to sell him the year’s crop. ‘It’s just a shade bitter, don’t you think, Bernard?’

‘Nescafé all tastes the same to me,’ I said.

‘This is pure chagga, ground just before it was brewed.’ He said it calmly but nodded to acknowledge my little attempt to annoy him.

‘Well, he didn’t turn up,’ I said. ‘We can sit here drinking chagga all morning and it won’t bring Brahms Four over the wire.’

Dicky said nothing.

‘Has he re-established contact yet?’ I asked.

Dicky put his coffee on the desk, while he riffled some papers in a file. ‘Yes. We received a routine report from him. He’s safe.’ Dicky chewed a fingernail.

‘Why didn’t he turn up?’

‘No details on that one.’ He smiled. He was handsome in the way that foreigners think bowler-hatted English stockbrokers are handsome. His face was hard and bony and the tan from his Christmas in the Bahamas had still not faded. ‘He’ll explain in his own good time. Don’t badger the field agents – that has always been my policy. Right, Bernard?’

‘It’s the only way, Dicky.’

‘Ye gods! How I’d love to get back into the field just once more! You people have the best of it.’

‘I’ve been off the field list for nearly five years, Dicky. I’m a desk man now, like you.’ Like you have always been is what I should have said, but I let it go. ‘Captain’ Cruyer he’d called himself when he returned from the Army. But he soon realized how ridiculous that title sounded to a Director-General who’d worn a General’s uniform. And he realized too that ‘Captain’ Cruyer would be an unlikely candidate for that illustrious post.

He stood up, smoothed his shirt, and then sipped coffee, holding his free hand under the cup to guard against drips. He noticed that I hadn’t drunk my chagga. ‘Would you prefer tea?’

‘Is it too early for a gin and tonic?’

He didn’t respond to this question. ‘I think you feel beholden to our friend Bee Four. You still feel grateful about his coming back to Weimar for you.’ He greeted my look of surprise with a knowing nod. ‘I read the files, Bernard. I know what’s what.’

‘It was a decent thing to do,’ I said.

‘It was,’ said Dicky. ‘It was a truly decent thing to do, but that wasn’t why he did it. Not only that.’

‘You weren’t there, Dicky.’

‘Bee Four panicked, Bernard. He fled. He was near the border, at some godforsaken little place in Thüringerwald, by the time our people intercepted him and told him he wasn’t wanted for questioning by the KGB – or anyone else, for that matter.’

‘It’s ancient history,’ I said.

‘We turned him round,’ said Cruyer. It had become ‘we’ I noticed. ‘We gave him some chickenfeed and told him to go back and play the outraged innocent. We told him to cooperate with them.’

‘Chickenfeed?’

‘Names of people who’d already escaped, safe houses long since abandoned … bits and pieces that would make Brahms Four look good to the KGB.’

‘But they got Busch, the man who was sheltering me.’

Unhurriedly, Cruyer finished his coffee and wiped his lips with a linen napkin from the tray. ‘We got two of you out. I’d say that’s not bad for that sort of crisis – two out of three. Busch went back to his house to get his stamp collection … Stamp collection! What can you do with a man like that? They put him in the bag of course.’

‘The stamp collection was probably his life savings,’ I said.

‘Perhaps it was, and that’s how they put him in the bag, Bernard. No second chances with those swine. I know that, you know that, and he knew it too.’

‘So that’s why our field people don’t like Brahms Four.’

‘Yes, that’s why they don’t like him.’

‘They think he informed on that Erfurt network.’

Cruyer shrugged. ‘What could we do? We could hardly spread the word that we’d invented that story to make the fellow persona grata with the KGB.’ Cruyer walked across to his drinks cabinet and poured some gin into a large Waterford glass tumbler.

‘Plenty of gin, not too much tonic,’ I said. Cruyer turned to stare blankly at me. ‘If that’s for me,’ I added. So there had been a blunder. They’d told Brahms Four to reveal old Busch’s address, then the poor old sod had gone back for his stamps. And run into the arms of a KGB arrest squad.

Dicky put a little more gin into the glass, and added ice cubes gently so that they would not splash. He brought it, together with a small bottle of tonic, which I left unused. ‘No need for you to concern yourself with this one any more, Bernard. You did your bit in going to Berlin. We’ll let one of the others take over now.’

‘Is he in trouble?’

Cruyer went back to the drinks cabinet and busied himself tidying away the bottle caps and stirrer. Then he closed the cabinet doors and said, ‘Do you know the sort of material Brahms Four has been supplying?’

‘Economics intelligence. He works for an East German bank.’

‘He is the most carefully protected source we have in Germany. You are one of the few people ever to have seen him face to face.’

‘And that was almost twenty years ago.’

‘He works through the mail – always local addresses to avoid the censors and the security – posting his material to various members of the Brahms net. In emergencies he uses a dead-letter drop. But that’s all – no microdots, no one-time pads, no codes, no micro transmitters, no secret ink. Very old-fashioned.’

‘And very safe,’ I said.

‘Very old-fashioned and very safe, so far,’ agreed Dicky. ‘Even I don’t have access to the Brahms Four file. No one knows anything about him except that he’s been getting material from somewhere at the top of the tree. All we can do is guess.’

‘And you’ve guessed,’ I prompted him, knowing that Dicky was going to tell me anyway.

‘From Bee Four we are getting important decisions of the Deutsche Investitions Bank. And from the Deutsche Bauern Bank. Those state banks provide long-term credit for industry and for agriculture. Both banks are controlled by the Deutsche Notenbank, through which come all remittances, payments and clearing for the whole country. Now and again we get good notice of what the Moscow Narodny Bank is doing and regular reports about the COMECON briefings. I think Brahms Four is a secretary or personal assistant to one of the directors of the Deutsche Notenbank.’

‘Or a director?’

‘All banks have an economics intelligence department. Being head of that department is not a job an ambitious banker craves for, so they get switched around. Brahms Four has been feeding us this sort of thing too long to be anything but a clerk or assistant.’

‘You’ll miss him. Too bad you have to pull him out,’ I said.

‘Pull him out? I’m not trying to pull him out. I want him to stay right where he is.’

‘I thought …’

‘It’s his idea that he should come over to the West, not mine! I want him to remain where he is. I can’t afford to lose him.’

‘Is he getting frightened?’

‘They all get frightened eventually,’ said Cruyer. ‘It’s battle fatigue. The strain of it all gets them down. They get older and they get tired and they start looking for that pot of gold and the country house with the roses round the door.’

‘They start looking for things we’ve been promising them for twenty years. That’s the truth of it.’

‘Who knows what makes these crazy bastards do it?’ said Cruyer. ‘I’ve spent half my life trying to understand their motivation.’ He looked out of the window. Hard sunlight sidelighting the lime trees, dark blue sky with just a few smears of cirrus very high. ‘And I’m still no nearer knowing what makes any of them tick.’

‘There comes a time when you have to let them go,’ I said.

He touched his lips; or was he kissing his fingertips, or maybe tasting the gin that he’d spilled on his fingers. ‘Lord Moran’s theory, you mean? I seem to remember he divided men into four classes. Those who were never afraid, those who were afraid but never showed it, those who were afraid and showed it but carried on with their job, and the fourth group – men who were afraid and shirked. Where does Brahms Four fit in there?’

‘I don’t know,’ I said. How the hell can you explain to a man like Cruyer what it’s like to be afraid day and night, year after year? What had Cruyer ever had to fear, beyond a close scrutiny of his expense accounts?

‘Well, he’s got to stay there for the time being, and there’s an end to it.’

‘So why was I sent to receive him?’

‘He was acting up, Bernard. He threw a little tantrum. You know the way these chaps can be at times. He threatened to walk out on us, but the crisis passed. Threatened to use an old forged US passport and march out through Checkpoint Charlie.’

‘So I was there to hold him?’

‘Couldn’t have a hue and cry, could we? Couldn’t give his name to the civil police and send teleprinter messages to the boats and airports.’ He unlocked the window and strained to open it. It had been closed all winter and now it took all Cruyer’s strength to unstick it. ‘Ah, a whiff of London diesel. That’s better,’ he said as there came a movement of chilly air. ‘But he’s still proving difficult. He’s not giving us the regular flow of information. He threatens to stop altogether.’

‘And you … what are you threatening?’

‘Threats are not my style, Bernard. I’m simply asking him to stay there for two more years and help us get someone else into place. Ye gods! Do you know how much money he’s squeezed out of us over the past five years?’

‘As long as you don’t want me to go,’ I said. ‘My face is too well known over there. And I’m getting too bloody short-winded for any strong-arm stuff.’

‘We’ve plenty of people available, Bernard. No need for senior staff to take risks. And anyway, if things went really sour on us, we’d need someone from Frankfurt.’

‘That has a nasty ring to it, Dicky. What kind of someone would we need from Frankfurt?’

Cruyer sniffed. ‘No need to draw you a diagram, old man. If Bee Four really started thinking of spilling the beans to the Normannenstrasse boys, we’d have to move fast.’

‘Expedient demise?’ I said, keeping my voice level and my face expressionless.

Cruyer became a fraction uncomfortable. ‘We’d have to move fast. We’d have to do whatever the team on the spot thought necessary. You know how these things go. And XPD can never be ruled out.’

‘This is one of our own people, Dicky. This is an old man who has served the Department for over twenty years.’

‘And all we’re asking,’ said Cruyer with exaggerated patience, ‘is for him to go on serving us in the same way. What happens if he goes off his head and wants to betray us is conjecture – pointless conjecture.’

‘We earn our living from conjecture,’ I said. ‘And it makes me wonder what I would have to do to have “someone from Frankfurt” come along to get me ready for that big debriefing in the sky.’

Cruyer laughed. ‘You always were a card!’ he said. ‘You wait until I tell the old man that one.’

‘Any more of that delicious gin?’

He took the glass from my outstretched hand. ‘Leave Brahms Four to Frank Harrington and the Berlin Field Unit, Bernard. You’re not a German, you’re not a field agent any longer, and you are far, far too old.’

He put a little gin in my glass and added ice, using claw-shaped silver tongs. ‘Let’s talk about something more cheerful,’ he said over his shoulder.

‘In that case, Dicky, what about my new car allowance? The cashier won’t do anything without the paperwork.’