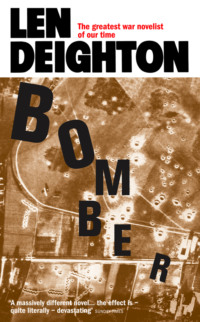

Bomber

Each day Batters hung round the ground crew of his aeroplane watching and asking endless questions in his thin high voice. While this added to his knowledge, it did nothing for his popularity. He watched Lambert all the time and hoped for nothing more than the curt word of praise that came after each flight. Batters was an untypical flight engineer. Most of them were more like Micky Murphy, practical men with calloused hands and an instinct for mechanical malfunction. They came from factories and garages, they were apprentices or lathe operators or young clerks with their own motorcycle that they could reassemble blindfold. Battersby would never have their instinct. He’d been a secondary-school boy with one afternoon a week in the metalwork class. Of course Batters could run rings round most of the Squadron’s engineers at written exams and luckily the RAF set high store by paperwork. His father taught physics and chemistry at a school in Lancashire.

I marked your last physics paper while on fire-watching. The headmaster was on duty with me. He’d given the sixth form the same sample paper but he told me that yours was undoubtedly the best. This, I need hardly say, made your father rather proud of you. I am confident however that this will not tempt you to slacken your efforts. Always remember that after the war you will be competing for your place at university with fellows who have been wise enough to contribute to the war in a manner that furthers their academic qualifications.

This week’s sample entrance paper should prove a simple matter. Perhaps I should warn you that the second part of question four does not refer solely to sodium. It requires an answer in depth and its apparent simplicity is intended solely to trap the unwary.

Mrs Cohen came into the breakfast room from the kitchen just as Battersby was helping himself to one pancake and a drip of honey. She was a thin white-haired woman who smiled easily. She pushed half a dozen more upon his plate. Battersby had that sort of effect upon mothers. She asked in quiet careful English if anyone else would like more pancakes. In her hand there was a tall pile of fresh ones.

‘They’re delicious, Mrs Cohen,’ said Ruth Lambert. ‘Did you make them?’

‘It’s a Viennese recipe, Ruth. I shall write it for you.’ They all looked towards Mrs Cohen and she cast her eyes down nervously. They reminded her of the clear-eyed young storm-troopers she had seen smashing the shopfronts in Munich. She had always thought of the British as a pale, pimply, stunted race, with bad teeth and ugly faces, but these airmen too were British. Her Simon was indistinguishable from them. They laughed nervously at the same jokes no matter how often repeated. They spoke too quickly for her, and had their own vocabulary. Emmy Cohen was a little afraid of these handsome boys who set fire to the towns she’d known when a girl. She wondered what went on in their cold hearts, and wondered if her son belonged to them now, more than he did to her.

Mrs Cohen looked at Lambert’s wife. Her WAAF corporal’s uniform was too severe to suit her but she looked trim and businesslike. At Warley Fen she was in charge of the inflatable rafts that bombers carried in case they were forced down into the sea. Nineteen, twenty at the most. Her wrists and ankles still with a trace of schoolgirl plumpness. She was clever, thought Mrs Cohen, for without saying much she was a part of their banter and games. They all envied Lambert his beautiful, childlike wife, and yet to conceal their envy they teased her and criticized her and corrected the few mistakes she made about their planes and their squadron and their war. Mrs Cohen coveted her skill. Lambert seldom joined in the chatter and yet his wife would constantly glance towards him, as though seeking approval or praise. Cheerful little Digby and pale-faced Battersby sometimes gave Lambert the same sort of quizzical look. So, noticed Mrs Cohen, did her son Simon.

It was eight-fifteen when a tall girl in WAAF officer’s uniform stepped through the terrace doors like a character in a drawing-room play. She must have known that the sunlight behind her made a halo round her blonde hair, for she stood there for a few moments looking round at the blue-uniformed men.

‘Good God,’ she said in mock amazement. ‘Someone has opened a tin of airmen.’

‘Hello, Nora,’ said young Cohen. She was the daughter of their next-door neighbour if that’s what you call people who own a mansion almost a mile along the lane.

‘I can only stay a millisecond but I must thank you for sending that divine basket of fruit.’ The elder Cohens had sent the fruit but Nora Ashton’s eyes were on their son. She hadn’t seen him since he’d gained his shiny new navigator’s wing.

‘It’s good to see you, Nora,’ he said.

‘Nora visits her mother almost every weekend,’ said Mrs Cohen.

‘Once a month,’ said Nora. ‘I’m at High Wycombe now, Bomber Command HQ.’

‘You must fiddle the petrol for that old banger of yours.’

‘Of course I do, my pet.’

He smiled. He was no longer a shy thin student but a strong handsome man. She touched the stripes on his arm. ‘Sergeant Cohen, navigator,’ she said and exchanged a glance with Ruth. It was all right: this WAAF corporal clearly had her own man.

Nora pecked a kiss and Simon Cohen briefly took her hand. Then she was gone almost as quickly as she arrived. Mrs Cohen saw her to the door and looked closely at her face when she waved goodbye. ‘Simon is looking fine, Mrs Cohen.’

‘I suppose you are surrounded with sergeants like him at your headquarters place.’

‘No, I’m not,’ said Nora. They seldom saw a sergeant at Bomber Command HQ, they only wiped them off the black-board by the hundred after each attack.

After they had finished eating Cohen passed cigars around. Digby, Sweet, and Lambert took one but Batters said his father believed that smoking caused serious harm to the health. Sweet produced a fine ivory-handled penknife and insisted upon using its special attachment to cut the cigars.

Ruth Lambert got up from the table first. She wanted to make sure their bedroom was left neat and tidy, no hairpins on the floor or face powder spilled on the dressing-table.

She looked back at her husband. He was a heavy man and yet he could move lightly and with speed enough to grab a fly in mid-air. His was a battered face and wrinkled too, especially round the mouth and eyes. His eyes were brown and deep-set with dark patches under them. Once she had written that his eyes were ‘smouldering’.

‘Then mind you don’t get burned, my girl.’

‘Oh Mother, you’ll both love him.’

‘Pity he can’t get a commission. Do him more good than that medal.’

‘A commission isn’t important, Father.’

‘Wait until you’re living in a post-war NCO’s Married Quarters. You’ll soon change your tune.’

He felt her looking at him. He looked up suddenly and winked. His eyes revealed more than he would ever speak. This morning for instance she had watched him while Flight Lieutenant Sweet was theorizing about engines, and had known that it was all nonsense by the amused shine in Sam’s eyes. Sam, I love you so much: calm, thoughtful and brave. She glanced at the other airmen around the table. It’s strange but the others seem to envy me.

Mrs Cohen also hastened away to pack her son’s case. Left to themselves the boys stretched their feet out. They were puffing stylishly at the large cigars, and clichés were exchanged across the table. They could talk more freely when a chap’s mother wasn’t there.

‘We’ll be on tonight,’ predicted Sweet. ‘I feel it in my corns.’ He laughed. ‘We’ll put a little salt on Hitler’s tail again, eh?’

‘Is that what we are doing?’ asked Lambert.

‘Certainly it is,’ said Sweet. ‘Bombing the factories, destroying his means of production.’ Sweet’s voice rose a little higher as he became exasperated by Lambert’s patronizing smile.

Cohen spoke for the first time. ‘If we are going to talk about bombing, let’s be as scientific as possible. The target map of Berlin is just a map of Berlin with the aiming-point right in the city centre. We are fooling only ourselves if we pretend we are bombing anything other than city centres.’

‘What’s wrong with that?’ said Flight Lieutenant Sweet.

‘Simply that there are no factories in city centres,’ said Lambert. ‘The centre of most German towns contains old buildings: lots of timber construction, narrow streets and alleys inaccessible to fire engines. Around that is the dormitory ring: middle-class brick apartments mostly. Only the third portion, the outer ring, is factories and workers’ housing.’

‘You seem very well informed, Flight Sergeant Lambert,’ said Sweet.

‘I’m interested in what happens to people,’ said Lambert. ‘I come from a long line of humans myself.’

‘I’m glad you pointed that out,’ said Sweet.

Cohen said, ‘One has only to look at our air photos to know what we do to a town.’

‘That’s war,’ said Battersby tentatively. ‘My brother said there’s no difference between bankrupting a foreign factory in peacetime and bombing it in wartime. Capitalism is competition and the ultimate form of that is war.’

Cohen gave a little gasp of laughter, but corrected it to a cough when Battersby did not smile.

Lambert smiled and rephrased the notion. ‘War is a continuation of capitalism by other means, eh, Batters?’

‘Yes, sir, exactly,’ said Battersby in his thin childish voice. ‘Capitalism depends upon consumption of manufactured goods and war is the most efficient manner of consumption yet devised. Furthermore, it’s a test of each country’s industrial system. I mean, look at the way we are developing our aeroplanes, radios, engines, and all sorts of secret inventions.’

‘What about man for man?’ said Digby.

‘Surely after the great victories of the Red Army you don’t still subscribe to the superhuman ethic, Mr Digby,’ said Battersby. ‘Evils may exist within our social systems but the working man who fights the war is pretty much the same the world over.’

They were all surprised to hear Battersby converse at length, let alone argue.

‘Are you a Red, Battersby?’ said Flight Lieutenant Sweet.

‘No, sir,’ said Battersby, biting his lip nervously. ‘I’m just stating what my brother told me.’

‘He should be shot,’ said Sweet.

‘He was, sir,’ said Battersby. ‘At Dunkirk.’

Sweet’s rubicund face went bright red with embarrassment. He stubbed his cigar into a half-eaten pancake and, getting to his feet, said, ‘Perhaps we’d best get cracking. Just in case there’s something on tonight.’

Digby and Battersby also went upstairs to pack. Lambert was silent, sipping at his coffee and watching the cigar smoke drifting towards the oak ceiling.

Cohen poured coffee for himself and Lambert. The two of them sat at the table in silence until Cohen said, ‘You don’t believe in this war?’

‘Believe in it?’ said Lambert. ‘You make it sound like a rumour.’

‘I think about the bombing a lot,’ admitted Cohen.

‘I hope you do,’ said Lambert. ‘I hope you worry yourself sick about it.’

On the Squadron Lambert usually spoke only of technical matters and like most of the old-timers he would smile without committing himself when politics or religion was discussed. Today was different.

‘What do you believe then?’

‘I believe that everyone is corruptible and I’m always afraid that I might become corrupt. I believe that all societies are a plot to corrupt the individual.’

‘That’s anarchy,’ said young Cohen, ‘and you are never an anarchist by any measure. After all, Skipper, society has a right to demand a citizen’s loyalty.’

‘Loyalty? You mean using another man’s morality instead of your own. That’s just a convenient way of putting your conscience into cold storage.’

‘Yes,’ reflected Cohen doubtfully. ‘The SS motto is “my honour is my loyalty”.’

‘Well, there you are.’

‘But what about family loyalty?’

‘That’s almost as bad: it’s giving your nephew the prize for playing the piano when the little boy down the street plays better.’

‘Is that so terrible?’ asked Cohen.

‘I’m the little boy down the street. I wouldn’t have even got as far as grammar school unless a few people had let a prize or two go out of the family.’

‘What you are really saying,’ said young Cohen trying to make it a question rather than a verdict, ‘is that you don’t like bombing cities.’

‘That is what I’m saying,’ said Lambert and the young navigator was too shocked to think of a reply. Lambert drained his cup. ‘That’s good coffee.’

Hastily Cohen reached for the pot to pour more for him. He wanted to demonstrate his continuing admiration and regard for his pilot. ‘Coffee isn’t rationed,’ said young Cohen.

‘Then fill her up, and give me two hundred Player’s.’

The roses on the table were now fully open. Lambert reached out to them but as he touched one it disintegrated and the pale-pink petals fell and covered the back of his hand like huge blisters.

‘Men are disturbed by any lack of order.’ The voice by his shoulder made Lambert start for old Mr Cohen had entered the room without either of them hearing him. He was a tall man with a handsome face, marred only by a lopsided mouth and yellow teeth. He spoke the careful style of English that only a foreigner could perfect. However a nasal drone accompanied his flat voice which gave no emphasis to any word nor acknowledged the end of a sentence.

‘You and I might be able to see the virtue of chaos,’ he continued, ‘but dictators gain power by offering pattern, ranks, common purpose, and men in formations. Men want order, they strive for it. Even the world’s artists are asked only to impose meaning and symmetry upon the chaos of nature. You and I, Sergeant Lambert, may know that muddle and inefficiency are man’s only hope of freedom but we will not easily convert our fellow men.’

‘You are mocking me, Mr Cohen.’

‘Not me, Sergeant. I have seen men line up to dig their own graves and turn to face the firing squad with a proud precision. I am not mocking you.’

‘The British are not easy to regiment, Father.’

‘So they keep telling me, my son, but I wonder. In this war they have gained the same sense of national identity and purpose that the Nazis gave the Germans. The British are so proud of their conversion that they will almost forgo their class system. I see the clear eyes and firm footfalls of the self-righteous and that is a good start on the road to totalitarian power. History is being quoted and patriotic songs revived. Believe me, the British are proud of themselves.’

There was a commotion outside as Digby stumbled down the stairs with his suitcase but Mr Cohen did not pause.

‘Some day, in the not-so-far-distant future, when the trade unions are being particularly tedious, students are being unusually destructive, and the pound is buying less and less, then a Führer will appear and tell the British that they are a powerful nation. “Britain Awake” will be his slogan and some carefully chosen racial minority will be his scapegoats. Then you will see if the British are easy to regiment.’

Sergeant Cohen smiled at Lambert. ‘For goodness’ sake don’t argue with him or we’ll be here all day.’ He got to his feet.

‘I wouldn’t mind that at all,’ said Lambert. The old man bowed courteously. As the two airmen went into the hall old Mr Cohen followed Lambert closely, as if to separate him from his son. Lambert turned to the old man and waited for him to speak but he didn’t do so until his son had left.

‘All fathers become old fools, Lambert,’ he said and then stopped. Lambert looked at him, trying to draw the words from him as one does with a man who stutters. The words again came in a rush: ‘You’ll look after the boy, won’t you?’

For a moment Lambert said nothing. Sweet came down the stairs. He took the old man’s arm and said airily, ‘Don’t worry about that, sir,’ but Cohen had selected only Lambert for his plea.

Lambert said, ‘It’s not my job to look after your son, sir.’

Young Cohen was still within earshot on the balcony above them. Digby saw him and felt like tugging the back of Lambert’s tunic in warning.

Lambert knew they were all listening but he didn’t lower his voice. He said, ‘It simply doesn’t work like that. A crew all need each other. Any one of them can endanger the aircraft. Your son is the most skilful navigator I’ve flown with, probably the best in the Squadron. He’s the brains of the aeroplane; he looks after us.’

There was silence for a moment, then Mr Cohen said, ‘He certainly should be good, he’s cost me a fortune to educate.’ The old man nodded to himself. ‘Look after my boy, Mr Lambert.’

‘I promise.’ Lambert nodded to the old man and hurried upstairs cursing himself for saying it. How the hell could he protect anyone? He was always amazed to get back safely himself. He passed young Cohen who was coming downstairs with a large case.

When he was alone with his son the old man said, ‘You hear that? Your Captain Lambert says you’re the best.’

Mrs Cohen appeared from nowhere and brushed her son’s coarse blue uniform distastefully.

‘His captain says he’s the best. Best on the Squadron, he said.’

Mrs Cohen ignored her husband. She pulled a piece of cotton from her son’s sleeve. ‘I see that Mr Sweet, the officer, is wearing gold cufflinks. Why don’t you take yours with you? They look so nice.’

‘Not in the Sergeants’ Mess, Mother.’

‘How old is Captain Lambert?’ she said.

‘He’s not a captain, Mother, he’s a flight sergeant. That’s one rank above mine. We call him captain because he’s the senior man on our aircraft.’

His mother nodded, trying to understand and remember.

‘Twenty-six or twenty-seven.’

‘He looks much older,’ said Mrs Cohen, looking at her son. ‘He looks forty, an old man.’

‘Do you want him to fly with a child?’ said Mr Cohen.

‘This Mr Sweet can help to make you an officer, Simon.’

‘Oh, Mother, you’ve been talking about me.’

‘Would it be so bad, Simon?’ said Mr Cohen.

‘It would mean changing to another crew.’

‘Why?’

‘They don’t like officers flying under NCO captains. Anyway, it would make Lambert’s job more difficult, having me sitting behind him with shiny little officer’s badges. And we wouldn’t be together in the Sergeants’ Mess. And perhaps I’d have to go away to a training school.’

‘Quite a speech,’ said Mr Cohen. ‘The most I’ve heard you say all weekend.’

‘I’m sorry, Father.’

‘It doesn’t matter. But if Mr Lambert is such a fine fellow, why is he not an officer? You tell me he has more experience, medals, and does the same job as your friend Mr Sweet.’

‘Surely you know the English by now, Father. Lambert has a London accent. He’s never been to an expensive school. The English believe that only gentlemen can be leaders.’

‘And this is the way they fight a war?’

‘Yes. Lambert is the best, most experienced pilot on the Squadron.’

Mrs Cohen said, ‘If you became an officer perhaps you could fly with Mr Sweet.’

‘I’d rather fly with Lambert,’ he replied, trying to keep his voice amiable.

She said, ‘You mustn’t be angry, Simon. We’re not trying to make you stop flying.’

‘That’s right. Just thinking of you earning more cash,’ his father joked.

‘I keep telling both of you I’m just not ambitious. I’m never going to be an officer and I’m never going to be a philosophy professor like Uncle Carol. Nor a scientist like dad. I’m not sure I could even run the farm. This job I’m doing in the Air Force …’

Cohen raised a finger to interrupt. ‘There is a common mistake made by historians: to review the past as a series of errors leading to the perfect condition that is the present time. It’s a common mistake in life too, especially in one of our closed societies like a school or a prison camp. It’s easy then to forget that the outside world or future time exist. Now in the middle of 1943 your Messrs Sweets and Lamberts seem to have attained the highest pinnacle of prestige and achievement. But it’s all glamour and tinsel. When the war is over, being the finest bomber crew that ever flew across Germany won’t get any of you so much as a free dog licence.’

‘You’ve got the wrong idea, Dad. I don’t like being in the Air Force. It’s dangerous and uncomfortable, and a lot of the people I work with are pretty nasty fellows.’ The old man looked up quizzically. ‘But if nasty fellows can destroy the Fascists I’ll put up with it. I know how to do my job theoretically at any rate so don’t worry about me. You’ve both got to understand that this is my life now. The whole of my life and I’ve got to live it in my own way. Without gold cufflinks or your talking to anyone about commissions or pocket money even. And most of all, no more parcels.’

Mrs Cohen nodded. ‘I understand, Simon, I always overdo things. I’ve embarrassed you with your captain, have I?’

‘No, no, no, it’s fine. It’s been a wonderful weekend and wizard food.’

‘Wizard,’ repeated Mrs Cohen, making a mental note of the superlative. She reached for her handbag but after a warning glance from her husband did not open it.

‘Have a good journey, Cosy,’ said his father.

‘My nickname is Kosher. Kosher Cohen they call me.’

‘So what’s wrong with that?’ asked his father. Kosher smiled but did not answer. The old man nodded and patted his son on the arm. They were closer than ever before.

‘Nora Ashton always asks about you,’ said Mrs Cohen. ‘She’s a fine girl.’

The hall clock struck nine. ‘I must go. They are waiting. There’s probably too much moon but we might fly tonight.’

‘Over Germany?’

‘There’s not time to go far on these short summer nights. Probably we’ll be dropping mines into the North Sea. All the boys like that, it’s a milk run but it counts as a full operation.’

Digby heard the last bit of that. ‘That’s right, Mrs Cohen, these gardening trips go off as quiet as a Sunday in Adelaide.’

‘Phone me in the morning, Simon.’

Chapter Two

‘One thing about these short summer nights,’ an elderly Wing Commander said, ‘we can usually shortlist the target files and have them in the old man’s hands the moment he makes the decision.’

Nora Ashton, the young WAAF officer, smiled at him briefly and then went back to checking the target files. Each one had been started on orders from the Targets Selection Committee at Air Ministry. She identified each file by its code name: Whitebait was Berlin and Trout was Cologne. The code names were the idea of the Senior Staff Officer, who was a keen angler. Recently he had taken up collecting butterflies and moths but the C-in-C said that code names like Broad-bordered Bee Hawk would be inconvenient. Inside each target file there were population figures, industrial descriptions, photos and intelligence about searchlights and guns. The files varied a great deal: some files were as fat as phone directories and packed with reports from resistance workers and secret agents, while many contained little that didn’t appear in a prewar city guide. Others were contradictory or out of date, and some were so thin that they scarcely existed at all. In each file there was a record of Bomber Command’s previous attacks.

‘The Ruhr tonight,’ said the elderly Wing Commander. ‘I’ll bet you my morning tea-break: Essen or Cologne.’

‘What, on my wages?’ said the WAAF officer. ‘When you buy three or four sticky buns.’

He shrugged. ‘You would have lost.’

Quickly she picked up a newspaper and turned to the astrology section. Under Aries it said, ‘Someone dear to you will make a journey. Financial affairs promising.’ She folded it and pushed it into the drawer.

She said, ‘Some day I’ll take you up on one of your bets. Anyway, look at the moon chart. After the casualties we’ve had on recent light nights they might decide a full moon is too dangerous.’

‘Too dangerous for some ops,’ said the Wing Commander, ‘but the Ruhr looks messy on radar screens. Moonlight gives a visual identification of the target. If the Met man predicts some cloud cover they’ll go, and the Ruhr’s the only logical target.’