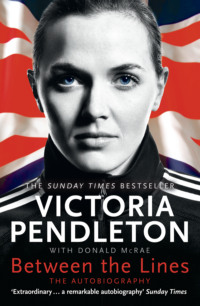

Between the Lines: My Autobiography

Max Pendleton was still a name, and a rider, to strike fear into the hearts of amateur cyclists across England. He was a winner. I remember going to track meetings with Dad when I’d hear other riders groan out loud and say, ‘Oh no, I can’t believe he’s here.’ They all knew that Max Pendleton would clean up. He’d win, pick up the prize money and go home.

Tough and aggressive, Dad was always the rider who attacked when everyone else was suffering. He would wait as long as it took for everyone else to start to wilt and then, showing no mercy, he would turn on the burners. I thought my dad was incredible.

Max Pendleton was good enough to make the black-and-white cover of Cycling Weekly – because he had been successful at national championship level. It made me proud to be his daughter. Secretly, I wanted to impress people like Max Pendleton did. I wanted to be really good at something; even if I didn’t know then what that ‘something’ might be or even how I might turn that feeling into words.

Something unusual began to take shape on a grass track in Fordham, a small village near Colchester in Essex. Alex and I stood next to our shiny new race bikes. We fiddled awkwardly with our helmets. It felt like a big block of polystyrene, covered by stretchy red, white and blue fabric, had been shoved on top of our heads. We looked ludicrous, and we knew it. We had just turned nine.

Nicola, who was fourteen, called her helmet a piss-pot. We all thought that was hysterical – and it took Nicky’s mind off cycling because she was far more interested in music. Nicky would have been happier performing a solo in the school orchestra, a challenge that would have scared me half to death. I felt safer on my bike, even with a massive piss-pot sliding off my head.

Dad never wore a helmet. He always rode hard and free. But we couldn’t escape the piss-pots. That year, in 1989, it had just been made legally binding for children to wear helmets in a race.

The Pendleton twins had their photo taken before our first-ever race in Fordham. Alex and I felt even more ridiculous, posing alongside our bikes. Our skinny arms stuck out of our baggy jumpers and our tiny legs looked strangely white beneath our black shorts. We were the only riders in the junior race that day. It was enough for me. I just wanted to beat Alex. Nothing else really mattered.

I felt amazingly close to Alex but I found it infuriating that, just because he was a boy, he was naturally stronger and faster than me. He was also much less fearful than me and had ridden his BMX far longer and more daringly than I had done on my bike. Years earlier, long before I felt confident enough to do so, Alex had asked for his stabilizers to be removed. I was more worried that I would fall off and hurt myself.

Alex was just better and braver than me. It wasn’t fair; and I was always trying to prove that I finally could match my twin for speed, endurance, efficiency, courage, tidiness, you name it. We all had the urge to beat each other. Even Nicola, when it came to war over Monopoly, was determined to win. It got very messy during board games. But, on our bikes, it was different. Alex still wanted to win but he was not as obsessed as me. He usually beat me but, on those rare occasions when I won while we were racing for fun at home, Alex just shrugged it off. I was much more like Dad. It felt important that I rode faster than Alex.

No more than thirty spectators stood around the track in Fordham. Most of them knew Dad and they must have been amused that his twins were the only two riders in the children’s race.

A Pendleton vs V Pendleton. A twin brother versus his twin sister. A boy against a girl.

I held the handlebars tight as we waited for the gun. The piss-pot felt heavy and unsteady on my head but I stared straight down the length of the grassy track. I could sense Alex at my side. He knew how much I wanted to beat him and so neither of us uttered a word.

Alex got away quicker than me, as usual, and he picked up speed down the long straight. I pedalled as fast as I could but the track was bumpy. Every time we hit another little mound of earth my helmet wobbled and slid down over my eyes. By the time I was about to take the first corner I was blinded by the piss-pot. I had to take a hand off the steering wheel and push the helmet back up my forehead. Alex had done the same. Our helmets were more likely to kill us than save us.

In between the bumps and the blinding moments I struggled to keep up with Alex in our one-lap race. Four hundred meters were just not long enough for me to haul my brother in – especially not with a piss-pot on my head. He won our first proper race. It was one-up to Alex, one for the boys.

I didn’t cry. I knew I’d be better next time. I would beat Alex one day in a proper race.

Dad was a man of achievement. He made things happen, often with his hands or the sheer force of his will. Dad might have made me feel bad some of the time but, still, I placed him high on a pedestal I built in my mind. I loved the fact that he was so practical and that he knew so much about everything. When he and Mum decided we needed to build an extension to the house, Dad did it himself. He learnt all he needed about the electrics and the plumbing; and he set about his work with drive and precision.

I liked helping Dad, and so I would pile up bricks in the wheelbarrow and move them to exactly where they were needed. Dad was cheerful. He even let me lay some of the bricks as he built our solid new extension. He taught me a lot and I could soon identify and hand him a jubilee clip. I was that sort of girl.

When Dad was in a good mood, no-one else in the whole wide world came close to being as much fun as him. I loved the fact that Dad still made us laugh uncontrollably and squeal when he took us out to fly our kites. We had many great days with Dad.

He could also be kind. Sometimes, when we were in the car, and driving to school or a race, and I felt nervous, Dad would lean across and squeeze my hand. He didn’t waste words but so much was packed into that gesture it felt as if he had steeled me for the trial ahead. At primary school, I hated being in the embarrassing group given extra maths and reading work while the rest of the class went off to assembly. But Dad always thought I was smart. And he knew I worked hard. Dad thought I would be alright because life was less about books and studying than living and learning out in the real world.

He and Mum took us on some wonderful holidays – with our bikes of course – to the Peak District and the Lake District. We also went cycling abroad, to stunningly beautiful places like the Pyrenees, and stayed in youth hostels where we met some intriguing people. Dad was happy that, through cycling, we were opening our minds. He also concentrated on his own distinct way of educating us.

It meant that, in the car, we had some traumatic clashes – usually over a map. Dad was fanatical about maps. He thought we should all learn how to read a map. And so, whenever we went somewhere new, and it was just me and Dad in the car, I would be the designated map-reader.

‘Where are you taking us?’ Dad would finally ask when my confused directions gave way to puzzled silence.

‘I don’t know where we are,’ I would admit.

‘Well, Victoria,’ Dad would reply, sighing with strained patience, ‘look at the map.’

‘I don’t understand the map,’ I’d say.

‘It’s all there – right in front of you,’ Dad snapped.

Even when I had sent us the wrong way, Dad would not turn back. That was impossible. We had to press ahead until I found a new way out of the mess I had made. Dad put a lot of pressure on me but, in the end, I learnt how to read a map.

I understood, deep down, that his unyielding way had been embedded into him during his childhood. He had been caned regularly at school and he remained a man who believed more in the proverbial old stick than the sweet and tasty carrot. Dad never smacked me but he did frighten me when he used his shouty voice. He was a very powerful figure and if I had to describe the dad of my girlhood years in one word I would say ‘extreme’. Dad either made me very happy or pretty miserable. There was not much bland stuff in between those extreme emotions.

Alex was smarter than me in dealing with Dad. Even when Dad got frustrated with him, Alex remained relaxed. ‘Oh Dad,’ he’d say, ‘it’ll be fine.’ Alex, in the end, was granted much more leeway than Nicky and me. We were indecisive and susceptible to Dad’s moods and whims. He steered us in directions that Alex avoided.

I couldn’t help but notice that Alex was cleverer than me at school, and much more popular. It didn’t upset me because I loved Alex. He deserved to be popular because he was so easy to be around. Alex helped me all through childhood – so much so that, on our first day of school, I’d been bewildered when so many kids burst into tears after their mothers left. I didn’t feel like crying. Why would I? At Etonbury Middle School in Stotfold I had Alex at my side. Even if I didn’t have many friends, I never felt lonely with Alex around. We were always in the same class and I worked hard.

As we prepared to move on to senior school, at the age of thirteen, I had caught up with Alex. But it was obvious that, unlike me, my brother could sail through our classes and exams. I could have followed Nicola to Bedford Girls – a public school where she did well academically and musically. Dad and Mum were willing to make the necessary sacrifice to pay for my and Alex’s senior education. But Alex was happy with an ordinary comprehensive and I preferred to stay with my twin. We moved together to Fearnhill School, in Letchworth, north Hertfordshire, just under four miles from where we lived in Stotfold.

Life became trickier. All the girls I knew at Brownies had mutated into ultra-cool teenagers who wouldn’t be seen dead with a bony runt like me. I was innocent and boring. At Fearnhill, I was consigned to the losers’ list. None of the cool girls wanted to do what I did – which was to play sport and listen to grungy, depressing music. They liked wearing make-up and learning how to smoke and pick up boys.

I much preferred playing hockey, where I suddenly became a very competitive girl, and riding on my bike with Dad and Alex every Sunday morning. Of course I was confused. I wished I could become both stronger and more feminine. But I drew pride from the fact that we rode so far with Dad every Sunday.

We racked up some big rides together. I remember telling my teacher at Fearnhill on a Monday morning that I had ridden fifty miles the previous day. ‘Fifteen!’ she said, as if I needed to be corrected. ‘No,’ I said quietly. ‘Fifty. Five-oh.’ I don’t think she believed me, even though she knew I was not a girl who usually lied. But Dad, Alex and I had really ridden fifty miles. We had stopped for a break in the middle but, still, fifty miles for a thirteen-year-old girl felt like an achievement.

Alex and I also won lots of little trophies at grass-track meetings around the Home Counties. They felt more like picnics than anything serious and we enjoyed racing each other and some of the same kids that popped up all over the place. The grass-tracks developed our bike-handling skills and, allied to the stamina we’d forged on our Sunday morning marathons with Dad, Alex and I began to win regularly. We’d come home and say to Mum: ‘Look what we won! Ta-dah!’ And we’d wave our small cups and plinths of bronze cyclists in the air.

Over the previous year, I had grown taller than Alex. Maturing more quickly than my brother, I no longer trailed behind him in speed and fitness. I also raced more often than Alex did in grass-track meetings because, so keen to please Dad, I hardly missed a competition. Alex was different. He didn’t feel compelled to go to the track every time with Dad.

Early in the summer of 1994, when we were thirteen-and-a-half, Alex and I went with Dad to the world’s oldest grass-track meeting. Heckington, for English amateur riders like Dad, was significant. Deep in Lincolnshire, at the famous Heckington Agricultural Show, national grass-track titles were decided on a narrow track where the turns were tight and the sidelines were crammed with spectators.

Dad was realistic about the limitations of amateur cycling. He always knew he would have to work either in accountancy or property management for a living. Cycling could never be more than a consuming hobby. But Dad loved winning at tracks like Heckington where there was more prestige at stake.

This time only Alex and I went to Heckington with Dad. Nicola, at eighteen, was physically talented and rode well, but she was far more intent on working towards her A-levels and Grade Eight exams in the piano and flute. Nicky had seen her chance to escape and she took it. But Dad’s cycling hooks had dug deep into Alex and, especially, me.

We raced at Heckington in a handicap for riders between the ages of nine and sixteen. I didn’t expect that, even in a handicap, I could beat boys of fifteen and sixteen. Victory for me would be racing faster than Alex. But I knew it was going to be difficult. As I had raced so much more than him that year, I was handicapped harder than Alex. I started behind him which meant I’d have to race considerably faster than my twin to overtake him.

On the start line I was determined and ready. I wore a more modern kind of piss-pot on my head. A properly fitting helmet meant that there were no moments of being blinded every time I hit a bump. It was just me and my bike – up against Alex and his bike. We knew we could beat the other kids.

My mind went blank at the gun and I pedalled hard. The grass track became a green blur beneath my tyres. Raising my head, I locked onto the flying figure of my twin. I knew I could catch him and, soon, the distance between us shrunk. It seemed much easier chasing Alex round a flat track than it did trying to haul in Dad on an unforgiving hill.

I caught and then passed Alex on the final bend. I powered away from him down the last straight. Dad watched silently as someone shouted out to him. ‘Gosh, Max,’ the man said, ‘your girl was phenomenal.’

Dad didn’t want to make a big fuss of me in front of Alex; but he then heard a more understated voice: ‘Pretty impressive …’

‘Yes,’ Dad said. ‘It was …’

He told me as much later, when we were on our own. I shrugged him off. Dad tried again. He thought I could become a special cyclist if I put my mind to it and tried hard. It looked as if I had real talent and a lovely, smooth style of riding. ‘Yeah, Dad, thanks,’ I said, thinking a duty-bound father was obliged to say such words. Strangely, in that rare moment between us, I simply forgot how difficult it was to win Dad’s praise. I just assumed he was going out of his way to be kind to me because I had won. It was only years later that I understood how, alongside the grass track at Heckington, Dad really did believe he had seen something magical in me. Dad began to imagine a life for me that he might have wished for himself.

The complications between me and Dad, perhaps as a consequence of Heckington, became more tangled. A familiar ritual, a mostly silent showdown, played out between us at home in Stotfold a year later. I had been invited to the movies by two of my friends. We all knew I was hardly inundated by bosom buddies and so such invitations carried real meaning and novelty inside their simple appeal. It was not the first time, but the opportunities for me to go the movies or even parties on a Saturday night with some friends were rare enough to be exciting. Mum and Dad reacted in typically contrasting ways.

As always, Mum was pleased. She thought it would be good for me to go out and enjoy myself. ‘You deserve some fun with your friends, Lou,’ Mum said.

Dad was different. Mum had already said it would be fine, but I felt the old dark pull towards him. Dad just grunted when I asked if it would be alright to go to the movies that evening. I repeated the question. Dad answered me finally but, with just two words, his response became more clouded.

‘Suit yourself …’ he said with a shrug.

That shrug said so much more than his words. The shrug spoke of the fact that I was meant to be riding with Dad the following day. That shrug reminded me how tired I would be in the morning if I went out on Saturday night. That shrug implied that there was nothing Dad could do if I couldn’t be bothered to ride properly on Sunday – our special day together. The shrug was a small masterpiece of emotional blackmail.

How could I suit myself when, so plainly, my going out didn’t suit Dad?

Dad would not reassure me. He had his plans for the weekend and it was up to me whether I fitted in with him. If I chose not to go riding he wouldn’t say anything. He would just get up early and go out on his bike on his own. But we both knew how disappointed Dad would be if I let him down. He probably wouldn’t speak to me much all weekend.

The mute pressure Dad exerted on me felt heavier than usual. Alex, having just turned fifteen with me on 24 September 1995, had opted out of cycling. Just like Nicky before me, he saw his chance and took it. Alex knew I wasn’t going to give up. I needed Dad’s approval too much to abandon my bike. I was in for the long haul. There was no need for Alex to force himself down the same tortuous path. Dad would be happy if he had just one of us, me, to ride with him every Sunday morning. Alex quietly gave up his bike. He had other interests to explore.

‘It’s just you now, Vic,’ I said to myself. ‘Just you.’

I felt more responsible than ever for Dad’s weekend mood. I couldn’t disappoint him. And, over the prospect of an ordinary night at the movies, it felt like I had hurt him to the core.

Rather than looking forward to a modest teenage night out I felt consumed by guilt. I was letting Dad down by even thinking of me and my friends before him and the bike. Dad, without really saying anything, made me feel terrible. I also knew he was right. I would be utterly rubbish on my bike if I woke up tired on Sunday morning. It was enough of a strain hanging onto Dad racing up a hill when I had slept well and felt fresh. So, as Dad stalked off to let me think about my decision, I crumbled inside.

I went to find Mum. She was sweet and generous. We all knew what Dad was like so I should do whatever made me happy. If I fancied the pictures, I should go with my friends. Grumpy old Dad would survive.

Those sensible words were difficult to follow. The old teeming emotions rose up inside me. Dad was very good at making me feel very bad. He left me in a tight little world of fear and guilt. It was not a great place to be, not at fifteen, and so I gave in to the inevitable.

I didn’t tell Dad but, quietly, almost furtively, I disappeared upstairs to call my friends. I was sorry, I said, but I couldn’t make it to the movies after all. I’d forgotten that I had to go training with my dad in the morning. They were mystified; but they also knew I had ridden my bike every Sunday morning for so long. I felt grim, of course, for letting them down. That seemed worse to me than the fact that I was the one who would miss out on the movies and a few hours of fun.

The only good thing, after putting down the phone, was knowing that I would have felt much worse if I had gone out with my friends. Dad would have really given me the silent treatment then.

Instead, later, as I went off to bed, he sounded almost cheerful. ‘See you in the morning, Vic,’ he called out. ‘Early start for us …’

I knew my place. I would be on my bike again in the morning. I would be the girl on the hill, chasing the fleeing and distant figure of her father.

‘’Night, Mum,’ I said as I turned to climb the stairs to my room. ‘’Night, Dad …’

Alex and I began to fight more, which was normal, but horrible for me as a teenage girl. It took a long time for me to forgive him after he read my diary one night and, the next morning, waltzed straight up to a boy in our class to blurt out that I fancied him. I could have curled up and died in a dark hole but, as that option wasn’t available, I just turned the most embarrassing shade of red and seethed inside. How could boys, especially my twin brother, be so unspeakably cruel?

I survived the diary humiliation. Yet the whole world, for a while, became a desolate place. I felt unloved and misunderstood – especially at school. I really did feel like killing myself. Of course I was never going to do anything so drastic. I was far too guilty a person to seriously contemplate anything as selfish as suicide – but I harboured grim fantasies and became more withdrawn.

Most other girls in my class, at the ages of fifteen and sixteen, were going out, getting drunk and talking about boys. A few of them were already having sex. I was different. I just wanted to play sport and look a little prettier and much less skinny. It wasn’t much to ask.

I also wanted to be a germ-free girl; and so I washed my hands incessantly. It was one way of keeping the world at bay and, I guess, trying to rid myself of the stain I felt on the inside. I didn’t want to walk around and spread my germs to everyone else. At the same time I already knew that the world had enough germs of its own. So even if I was scrupulous about not passing on my bugs it became increasingly important that I did not pick up anyone else’s germs. Every time I had to open a door it became a real issue. It was impossible to use my hands, for fear of either spreading old germs or catching new germs, and so I had to stick out a foot, lean down with an elbow or, more self-consciously, use my bum to push open a door. I got into a right old state if the door could only be opened by swinging it towards me. In those difficult encounters I preferred to hang around until someone opened the door from the other side.

My hands were still exposed. They were germ-breeders and germ-magnets. The only solution was to wash them repeatedly. I scrubbed them with soap and held them under hot water until they looked red and raw. They were not so pretty, then, but at least I knew they were clean. Well, they were clean for a while until, naturally, they felt germ-ridden again.

The compulsive washing of my hands drove Dad mad. ‘That’s enough!’ he would shout. ‘Stop it.’

I got it under control after a while but, well, the germ paranoia never really went away. A grubby door handle and a public loo still unsettled me. I would do anything to avoid them. The hand-washing, however, dried up. Dad wasn’t going to allow me to get away with that for long.

It also helped that, finally, I began to make some real friends. We had little in common – apart from the obvious fact that we were the waifs and strays, the misfits left loitering far from the cool kids. We also tended to work hard and get irritated that most of our teachers seemed unable to quell the unruly mob that caused havoc in class. Those kids didn’t care about learning or working, but we did – which automatically made us even weirder to everyone else. Our weirdness bound us together.

We were just a small group at first – Cassie, Katie, Ruth, Anna, Helen and me – but by the time we reached the sixth form we had grown in confidence and numbers. Ten or eleven of us hung out together at lunchtime. We did well in class and began to feel that, rather than being the crazy outsiders, maybe we were the normal kids. Perhaps the cool kids were really the weird losers after all.

I also began to challenge Dad. At sixteen I started to question his authority just a little. I even managed, wonder of wonders, to go out on some Saturday evenings with my friends. It was never anything more outrageous than visiting the village pubs with some girls and boys, and I’d fret terribly if I missed my 10pm curfew by a few minutes. I still went riding on my bike with Dad the following morning; but life had begun to open up.

Cycling also became more successful for me. I won lots of competitions on the grass tracks of southeast England and started to enjoy the limited amount of prize money I was given after each victorious race.

Dad kept telling me that I was improving at an extraordinary rate. He thought I had the potential to be an amazing cyclist. Dad said I might be good enough to become a world champion one day.