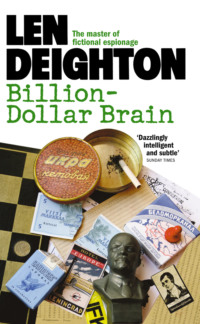

Billion-Dollar Brain

‘Exactly,’ said Dawlish. ‘Your plane leaves at nine fifty A.M. That gives you well over sixteen hours to arrange it.’

‘I’m overworked already.’

‘Being overworked is just a state of mind. You do far more work than you need on some jobs, less than you need on others. You should be more impersonal.’

‘I don’t even know what I’m supposed to do if I go to Helsinki.’

‘See Kaarna. Ask him about this article he’s preparing. He’s been silly in the past; show him a couple of pages of his dossier. He’ll be sensible.’

‘You want me to threaten him?’

‘Good heavens no. Carrot first: stick last. Buy this article he’s written if necessary. He’ll be sensible.’

‘So you keep saying.’ I knew it was no good betraying even the slightest amount of excitement. Patiently I said, ‘There are at least six men in this building who could do this job, even if it’s not as simple as you describe. I speak no Finnish, I have no close friends there, I’m not familiar with the country nor have I been handling any file that might have a bearing on this job. Why do I have to go?’

‘You,’ said Dawlish removing his spectacles and ending the discussion, ‘are the one best protected against cold.’

Old Montagu Street is a grimy slice of Jack-the-Ripper real-estate in Whitechapel. Dark grocers’ shops, barrels of salt herring; a ruin; a kosher poultry shop; jewellers; more ruins. Here and there tiny groups of newly painted shops carry Arabic signs as a fresh wave of underprivileged immigrants probes into the ghetto. Three dark-skinned children on old bicycles pedalled away quickly, circled and stopped. Beyond the tenements the shops began again. One, a printer’s, had fly-specked business cards in the window. The printed lettering had faded to pale pastel colours and the cards were writhing and twisting with bygone sunlight. The children made another sudden sortie on their bicycles, leaving arabesques in the thin skin of snow. The door was stiff and warped. Above my head a small bell jangled and shed dust. The children watched me enter the shop. Inside the small front office there was an ancient counter, topped with a slab of glass. Under the glass were examples of invoices and business cards: faded ghosts of failed businesses. On a shelf there were boxes of paper clips, office sundries, a notice that said ‘We take orders for rubber stamps’ and a greasy catalogue.

As the bell echoes faded a voice from the back room called, ‘You the one that phoned?’

‘That’s right.’

‘Go on up, luv.’ Then very loudly in a different sort of voice she screamed, ‘He’s here, Sonny.’ I opened the counter-flap and felt my way up the narrow stairs.

At the rear, grey windows looked down upon yards cluttered with broken bicycles and rusty hip-baths all painted with a thin film of snow. The scale of the place seemed too small for me. I’d wandered into a house built for gnomes.

Sonny Sontag worked at the top of the building. This room was cleaner than any of the others but the clutter was worse. A table with a white plastic surface occupied much of the room. On the table there were jam-jars crammed with punches, needles and scrapers, graving tools with wooden mushroom heads that fit into the palm of the hand, and two shiny oilstones. Most of the wall space was filled with brown cardboard boxes.

‘Mr Jolly,’ said Sonny Sontag, extending a soft white hand that gripped like a Stillson wrench. The first time I ever met Sonny he forged a Ministry of Works pass for me in the name of Peter Jolly. Since that day, with a faith in his own handiwork that typified him, he always called me Mr Jolly.

Sonny Sontag was an untidy man of medium height. He wore a black suit, black tie and a black rolled-brim hat which he seldom removed. Under his open jacket there was a hand-knitted grey cardigan from which hung a loose thread. When he stood up he tugged at the cardigan and it came a little more unravelled.

‘Hello, Sonny,’ I said. ‘Sorry about this rush.’

‘No. A regular customer should expect special consideration.’

‘I need a passport,’ I said. ‘For Finland.’

Looking like a hamster dressed in a business suit, he lifted his chin and twitched his nose while saying ‘Finland’ two or three times. He said, ‘Mustn’t be Scandinavian, too easy to check the registration. Mustn’t be a country that needs a visa for Finland because I haven’t time to do a visa for you.’ He wiped his whiskers with a quick movement. ‘West Germany; no.’ He went humming and twitching around the shelves until he found a large cardboard box. He cleared a space with his elbows, then just as I thought he was going to start nibbling at the box he tipped its contents across the table. There were a couple of dozen mixed passports. Some of them were torn or had corners cut and some were just bunches of loose pages held together with a rubber band. ‘These are for cannibalizing,’ explained Sonny. ‘I take out pages with visas I need and doctor them. For cheap jobs – the hoop gamefn1 – no good for you, but somewhere here I have a lovely little Republic of Ireland. I’d have it ready in a couple of hours if you fancy it.’ He scuffed through the mangled documents and produced an Irish passport. He gave it to me to look at and I gave him three blurred photos. Sonny studied the photos carefully and then brought a notebook from his pocket and read the microscopic writing at closer range.

‘Dempsey or Brody,’ he said, ‘which do you prefer?’

‘I don’t mind.’

He tugged at his cardigan, a long strand of wool fell away. Sonny wound it quickly round his finger and broke it free.

‘Dempsey then, I like Dempsey. How about Liam Dempsey?’

‘He’s a darling man.’

‘I wouldn’t attempt an Irish accent, Mr Jolly,’ said Sonny, ‘it’s very difficult the Irish.’

‘I’m joking,’ I said. ‘A man with a name like Liam Dempsey and a stage Irish accent would deserve all he got.’

‘That’s right, Mr Jolly,’ said Sonny.

I got him to pronounce it a couple of times. He was good with names and I didn’t want to go around mispronouncing my own name. I stood against the measure on the wall and Sonny wrote down 5?, 11?, blue eyes, dark-brown hair, dark complexion, no visible scars.

‘Place of birth?’ inquired Sonny.

‘Kinsale?’

Sonny sucked in a breath of noisy disagreement. ‘Never. Tiny place like that. Too risky.’ He sucked his teeth again. ‘Cork,’ he said grudgingly. I was driving a hard bargain. ‘OK Cork,’ I said.

He walked back around the desk making little disapproving sounds with his lips and saying, ‘Too risky Kinsale,’ as if I had tried to outsmart him. He pulled the Irish passport towards him and then turned up the cuffs of his shirt over his jacket. He put a watchmaker’s glass into his eye and peered closely at the ink entries. Then he stood up and stared at me as though comparing.

I said, ‘Do you believe in reincarnation, Sonny?’ He wet his lips and smiled, his eyes shining at me as though seeing me for the first time. Perhaps he was, perhaps he was discreet enough to let his clientele pass unseen and unremembered. He said, ‘Mr Jolly, I see men of all kinds in my establishment. Men to whom the world has been unkind and men who have been unkind to the world, and believe me they are seldom the same men. But men do not escape the world except by death. We all have our appointments in Samarra. That great writer Anton Chekhov tells us, “When a man is born he can choose one of three roads. There are no others. If he takes the road to the right, the wolves will eat him up. If he takes the road to the left he will eat up the wolves. And if he takes the road straight ahead of him, he’ll eat himself up.” That’s what Chekhov tells us, Mr Jolly, and when you leave here tonight you’ll be Liam Dempsey, but you won’t discard anything in this room. Destiny has given all her clients a number’ – he swept a hand across the numbered cardboard boxes – ‘and no matter how many changes we make she knows which number is ours.’

‘You’re right, Sonny,’ I said, surprised at mining a rich vein of philosophy.

‘I am, Mr Jolly, believe me, I am.’

2

Finland is not a communist satellite, it is a part of western Europe and shares its prosperity. The shops are jammed full of beefsteaks and LP records, frozen food and TV sets.

Helsinki airport is not a good place from which to make a confidential phone call. Airports seldom are: they use rural exchanges, record calls and have too many cops with time on their hands. So I took a taxi to the railway station.

Helsinki is a well-ordered provincial town where it never ceases to be winter. It smells of wood-sap and oil-heating, like a village shop. Fancy restaurants put smoked reindeer tongue on the menu next to the tournedos Rossini and pretend that they have come to terms with the endless lakes and forests that are buried silent and deep out there under the snow and ice. But Helsinki is just the appendix of Finland, an urban afterthought where half a million people try to forget that thousand upon thousand square miles of desolation and Arctic wasteland begin only a bus-stop away.

The taxi pulled in to the main entrance of the railway station. It was a huge brown building that looked like a 1930 radio set. Sauna-pink men hurried down the long lines of mud-spattered buses, and every now and again there would be a violent grinding of gears as one struck out towards the long country roads.

I changed a five-pound note in the money exchange, then used a call-box. I put a twenty-penni piece into the slot and dialled. The phone was answered very promptly, as though they were sitting on it at the other end.

I said, ‘Stockmann?’ It was the largest department store in Helsinki and a name that even I could pronounce.

‘Ei,’ said the man at the other end. ‘Ei’ means ‘no’.

I said ‘Hyvää iltaa,’ having practised the words for ‘good evening’, and the man at the other end said ‘Kiitos’ – thank you – twice. I hung up. I hailed another cab in the forecourt. I tapped the street map and the driver nodded. We pulled away into the afternoon traffic of the Aleksanterinkatu and finally stopped at the waterfront.

It was mild in Helsinki for the time of year. Mild enough for the ducks in the harbour to have a couple of man-made breaks in the ice to swim on, but not so mild that you could go around without a fur hat unless you wanted your ears to fall off and shatter into a thousand pieces.

One or two tarpaulin-covered carts marked the site of the morning market. The great curve of the harbour was white; the churned water frozen into dirty boulders of ice. A small knot of soldiers and an army lorry were also waiting for the ferry. Now and again they laughed and punched each other playfully and their breath rose like Indian signals.

The ferry arrived following the clear channel of broken ice which grudgingly permitted its passage. The boat hooted and the freezing air formed new scar tissue over the wet wound of its path. I lit a Gauloise under cover of the bulkhead and watched the army lorry crawl up the loading ramp. Standing in the market-place beyond there was a man with a tall column of hydrogen-filled balloons. The wind caught them and they wavered over him like a brightly coloured totem that he couldn’t quite balance. A grey-haired businessman in an astrakhan hat spoke briefly with the balloon-seller. The balloon-seller nodded towards the ferry. The grey-haired man didn’t buy. I felt the roll of the boat under the weight of the lorry. There was a hoot to warn the last passengers and a thrash of water before the stubby bow chopped back into the dense floating ice.

The grey-haired man joined me on the deck. He was big, and made even bigger by his heavy overcoat. The grey astrakhan hat and the fur collar exactly matched his hair and got mixed into it when he turned his head towards the sea. He was smoking a pipe and the wind blew sparks from it as he came through the door. He leaned over the rail beside me and we both watched the great heaving slabs of ice. It looked like every cabaret act of the thirties had tipped its white grand piano into this harbour.

‘Pardon me,’ said the grey-haired man. ‘Do you happen to know the phone number of Stockmann’s department store?’

‘It’s 12 181,’ I said, ‘unless you want the restaurant.’

‘The restaurant number I know,’ said the man. ‘It’s 37 350.’

I nodded.

‘Why have they started all this?’

I shrugged. ‘Someone in the Organization Department read one of those spy books.’ The man flinched a bit at the ‘spy’. It was one of those words to avoid, as the word ‘artist’ is avoided by painters. He said, ‘It takes me all my time to remember which bits you say and which bits I say.’

‘Me too,’ I said. ‘Perhaps we’ve both been saying it the wrong way round.’ The man in the fur collar laughed and more sparks flew from his pipe bowl. ‘There are two of them, as your message said. They are both in Hotel Helsinki and I think they know each other even though they’re not talking.’

‘Why?’

‘Well last night they were the only two people in the dining-room. They both ordered in English loud enough for the other to hear, and yet they didn’t introduce themselves. I mean, two Englishmen in a foreign country dining alone and not even exchanging a greeting. I mean, is it natural?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

The grey-haired man puffed at his pipe and nodded, carefully noting my reply and adding it to his experience. ‘One is about your height, leaner – perhaps seventy-five kilos – clean-shaven, clear voice, walks and talks like an Army officer; about thirty-two. The other is even taller, talks very loudly in an exaggerated English accent, very white face, ill at ease, about twenty-seven years old, thin, maybe weighs …’

‘OK,’ I said. ‘I’ve got the picture. The first will be Ross’s man that the War Office have sent, the other from FO.’

‘I would think that too. The first one, who is registered as Seager, had a drink with your military attaché early yesterday evening. The other calls himself Bentley!’

‘You’ve really been thorough,’ I said.

‘It’s the least we can do.’ He suddenly pointed across the frozen sea as someone walked out on to the deck behind us. We stared at one of the ice-locked islands as if we had just exchanged a juicy piece of information about it. The newcomer stamped his feet. ‘One Finnmark,’ he said. He collected the fare hastily and turned back into the warm cabin.

I said, ‘Apart from these public-school punters are there other foreign contacts with Kaarna?’

‘It’s hard to say. The town is full of strange people; Americans, Germans, even Finns who dabble a little in …’ he wriggled his fingers to find a word ‘… informations.’

Across the ice I could see the island of Suomenlinna and a group of people waiting for the boat. ‘My two haven’t visited Kaarna?’ The man shook his head. ‘Then it’s time someone did,’ I said.

‘Will there be trouble?’ We were nearly there now. I heard the driver starting the lorry. ‘Don’t worry,’ I said. ‘This isn’t that sort of job.’

I woke up in the Hotel Helsinki at seven the next morning. Someone was coming into my room. The waitress put the tray down beside my bed. Two cups, two saucers, two pots of coffee, two of everything. I tried to look like a man with a friend in the bathroom. The waitress opened the shutters and let the cold northern light fall across my bed. When she had gone I dissolved half a packet of laxative chocolate into each pot of coffee. I rang for room service. A man came. I explained that there was some mistake. The coffee was for the two men down the hall, Mr Seager and Mr Bentley. I gave him their room number and a one-mark note. Then I showered, shaved, dressed and checked out of the hotel.

I walked across the street to the first-floor shopping promenade where the charladies were flicking a final mop across the shiny floors of unopened shops. Two fur-hatted cops were eating breakfast in the Columbia Café. I took a seat near the window and stared across the square to the Saarinen railway station which dominated the town. More snow had fallen during the night and a small army of shovellers were clearing the bus-park.

I ate my breakfast. Kellogg’s Riisi Muroja went ‘snap, crackle, pop’, the eggs were fine and so was the orange juice, but I didn’t fancy coffee that morning.

Helsinki is only a kilometre wide at the end of the peninsula. Here in the south part of the town where the diplomats live and work, the old-fashioned granite buildings are quiet and parking is easy. Kaarna lived in a broody block of flats that still bore the scars of Russian attacks. Inside the foyer the furnishing had that restrained, colourless elegance that steel, glass and granite invariably produce. Kaarna’s flat was on the fourth floor: No. 44. A small light behind the bell-push said Dr Olaf Kaarna. I rang the bell three times. I had no appointment with Kaarna but I knew that he worked at home and seldom left his flat before lunch-time. I hit the buzzer again and wondered if he was struggling into his bathrobe and cursing. There was still no reply, and looking through the letter-box I could see only a dark hall-stand piled high with mail and three closed doors. I felt the cold metal of the letter-box against my forehead slide gently forward with a click. The heavy door swung open and almost toppled me across the welcome mat. I pushed the buzzer again, holding the door open with my toe as though I wasn’t really doing it. When it became evident that no one was going to come I moved quickly. I flipped through the pile of mail, and then into all the rooms. A kitchen, as tidy as you can get without dismantling the furniture. The lounge looked like the Scandinavian-modern department of a big store. Only the study looked lived-in. Books covered the walls and papers were untidily heaped across the pine desk. Bottles of ink and wire staples were used as paper-weights. Behind the desk was a glass-fronted bookcase, inside which were rows of expanding files neatly titled in Finnish. There was a rack of test-tubes, clean and unused, on the window-sill, and under the window a secretary’s desk with a sheet of -.25 FM stamps, a letter-opener, a balance, a bottle of gum, an empty bottle of nail varnish and a trace of spilled face powder. I found Kaarna in the bedroom.

Kaarna was a smaller man than his photos suggested and upside down the globular head was far too large for his body. The top of his bald head brushed lightly upon the superb carpet. His mouth was open enough to reveal his uneven upper teeth and from it blood had run along his nose and into his eyes, ending in a sort of Rorschach caste-mark in the centre of his forehead. His body was sprawled across the unmade bed with one shoe trapped in the bed-head, which prevented him sliding to the floor. Kaarna was fully dressed. His polka-dot bow tie was twisted up under his collar and his white nylon laboratory coat was smothered in raw egg, still slimy and fresh. Kaarna was dead.

There was blood low down on the left side of his back. It looked dark, like a blood-blister, under the non-porous nylon coat. The window was wide open and, though the room was freezing cold, the blood was still haemoglobin-fresh. I inspected his short clean fingernails where the lecturers tell us we’ll find all sorts of clues, but there was nothing there that could be seen without an electron microscope. If he had been shot through the open window it would account for his being thrown back across the bed. I decided to look for bruising around the wound, but as I gripped him by the shoulder he began to slide – he hadn’t even begun to stiffen – falling into a twisted heap on the floor. It was a loud noise and I listened for any movement from the flat below. I heard the lift moving.

Logically my best plan would have been to remain there, but I was in the hall, wiping doorknobs and worrying whether to steal the mail before you could say ‘scientific investigator’.

The lift stopped at Kaarna’s floor. A young girl got out of it, closing the gate with care before looking towards me. She wore a white trench-coat and a fur hat. She carried a briefcase that appeared to be heavy. She came up to the locked door of No. 44 and we both looked at it for a moment in silence.

‘Have you rung the bell?’ she said in excellent English. I suppose I didn’t look much like a Finn. I nodded and she pressed the bell a long time. We waited. She removed her shoe and rapped on the door with the heel. ‘He’ll be at his office,’ she pronounced with certainty. ‘Would you like to see him there?’ She slipped her shoe on again.

London said he didn’t have an office and that wasn’t the sort of thing that London got wrong. ‘I certainly would,’ I said.

‘Do you have papers or a message?’

‘Both,’ I said. ‘Papers and a message.’ She began to walk towards the lift, half-turning towards me to continue the conversation. ‘You work for Professor Kaarna?’

‘Not full time,’ I said. We went down in the lift in silence. The girl had a clear placid face with the sort of flawless complexion that responds to cold air. She wore no lipstick, a light dusting of powder and a touch of black on the eyes. Her hair was blonde but not very light and she’d tucked it up inside her fur hat. Here and there a strand hung down to her shoulder. In the foyer she looked at the man’s wristwatch she was wearing.

‘It’s nearly noon,’ she said. ‘We would do better to wait till after lunch.’

I said, ‘Let’s try his office first. If he’s not there we’ll have lunch near by.’

‘It’s not possible. His office is in a poor district alongside highway five, the Lahti road. There is nowhere to eat around there.’

‘Speaking for myself …’

‘You are not hungry.’ She smiled. ‘But I am, so please take me to lunch.’ She gripped my arm expectantly. I shrugged and began to walk back towards the centre of town. I glanced up at the open window to Kaarna’s flat; there were plenty of places in the building opposite where a rifleman could have sat waiting. But in this sort of climate where the double-glazed windows are sealed with tape a man could wait all winter.

We walked up the wide streets on pavements that were brushed in patterns around humps of recalcitrant ice like a Japanese sand-garden. The signs were incomprehensible and consonant-heavy except for words like Esso, Coca-Cola and Kodak sandwiched between the Finnish. The sky was getting greyer and lower every moment, and as we entered the Kaartingrilli Café small businesslike flakes began to fall.

The Kaartingrilli is a long narrow place full of heated air that smells of coffee. Half of the wall space is painted black and the other half is picture windows. The décor is all natural wood and copper and the place was crowded with young people shouting, flirting and drinking Coca-Cola.

We sat down in the farthest corner staring out across a crowded car-park where every car was white with snow. With her heavy coat off the girl was much younger than I thought. Helsinki teems with fresh-faced girls born when the soldiers returned home. Nineteen forty-five was a boom year for gorgeous Finns. I wondered whether this girl was one of them.

‘I am Liam Dempsey, a citizen of Eire,’ I said. ‘I have been gathering material for Professor Kaarna in connexion with a transfer of funds between London and Helsinki. I live in London most of the year.’ She presented her hand across the table and I shook it. She said, ‘My name is Signe Laine. I am a Finn. You work for Professor Kaarna, then we shall get along swell because Professor Kaarna works for me.’

‘For you,’ I said without making it a question.

‘Not for me personally,’ she smiled at the thought. ‘For the organization that employs me.’

She held her hands as though she’d seen too many copies of Vogue, picking up one hand with the other and holding it against her face and nursing it as if it was a sick canary.

‘What organization is that?’ I asked. The waitress came to our table. Signe ordered in Finnish without consulting me.

‘All in good time,’ she said. Outside in the car-park the wind was carrying the snow in horizontal streaks and a man in a woollen hat with a bobble on it was struggling along with a car battery, leaning into the wind and trying not to slip on the hard, shiny, grey ice.