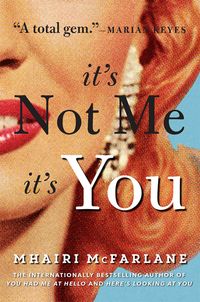

It’s Not Me, It’s You

‘Who’s written lyrics like Joy Division’s “Love Will Tear Us Apart” in the last ten years?’ Paul continued now, still on modern music in the present day.

‘What’s the one about “that isn’t my name”? Na na na, they call me DYE-ANNE, that’s not my name …’

Paul made a sad face, and a gesture to the waiter for the bill.

‘You love playing the codger, despite being the biggest child I know,’ Delia said, and Paul rolled his eyes and patted her hand across the table. Kids. She imagined Paul as a father, and her heart gave a little squeeze.

They settled up and stepped out into the brisk chill of an early Newcastle summer evening.

‘Nightcap?’ Paul said, offering her the crook of his arm.

‘Can we go for a walk first?’ Delia said, taking it.

‘A walk?’ Paul said. ‘We’re not in one of those films you like with the parasols and people poking the fire. We’re going to walk to the pub.’

‘Come on! It’s our ten-year anniversary. Just onto the bridge and back.’

‘Oh no, c’mon. It’s too late. Another time.’

‘It won’t take long,’ she said, forcibly manoeuvring him onward, as Paul exhaled windily.

They set off in silence – Paul possibly resentful, Delia twanging with nerves as she wondered if this surprise was such a good idea after all.

Three

‘What are we going to do when we get there?’ Paul said, with both humour and irritation in his voice.

‘Share a moment.’

‘I could be sharing the moment of being in a warm pub with a nice pint.’

Paul didn’t do showy romance or I love yous. (Delia had to ask him, months into their relationship. He blanked. ‘Why else did I ask you to move in?’ Because my lease was up on the other place? Delia had thought.)

Simple, self-evident, uncomplicated affection was all Delia needed, usually. Solidity and companionship mattered much more to her than bouquets or jewellery. Paul was her best friend – and that was more romantic than anything.

And she loved this city, with its handsome blocks of sandstone buildings, low skies, rich voices and friendly embrace. As she tottered down the steep street to the Quayside, breathing the fresher air near the river, clutching Paul’s arm to steady her, she knew she was in the right place, with the right person.

The sodium orange and yellow lights from the city tiger-striped the oil-black water of the Tyne as they arrived at the mouth of the Millennium Bridge. The thin bow, pulsing with different colour illuminations, was glowing red.

It felt like a sign. Red shoes, red hair, red bicycle. For some reason, the phrase date with destiny came into her head, which sounded like an Agatha Christie novel. There weren’t many people about, but enough that they weren’t alone. Whoops, why hadn’t Delia thought of that? All they needed was some persistent hanger-abouters and this plan would be sunk. But in this temperature, loitering on bridges at pushing nine o’clock was not a particularly popular choice.

She felt her heartbeat in her throat as they approached the midway point. The moment was arriving.

‘Do we have to walk the whole way or will this do?’ Paul said.

‘This’ll do,’ Delia said, disentangling herself from his arm. ‘Doesn’t the city look great from here?’

Paul scanned the view and smiled.

‘How pissed are you? Hang on, it’s not the time of the month? You’re not going to cry about that lame beggar seagull with one eye and one leg again? I told you, all seagulls are beggars.’

Delia laughed.

‘He was probably faking.’ Paul squeezed one eye closed and bent a leg behind him, speaking in a squeaky pitch. ‘Please give chips genewously to a disabled see-gal, lubbly lady. Mah situation is mos pitiable.’

Delia laughed harder. ‘What voice was that?’

‘A scam artist seagull voice.’

‘A Japanese scam artist seagull?’

‘Racist.’

They were both laughing. OK, he’d perked up. Deep breath. Go. It was stupid of her to be nervous, Delia thought: she and Paul had discussed the future. They’d lived together for nine years. It wasn’t like she was up the Eiffel Tower and out on a limb with a preening commitment-phobe, after a whirlwind courtship.

Paul started to grumble about the brass bollocks temperature and Delia needed to interrupt.

‘Paul,’ she said, turning to face him fully. ‘It’s our ten-year anniversary.’

‘Yes …?’ Paul said, for the first time noticing her sense of intent.

‘I love you. And you love me, I hope. We’re a great team …’

‘Yeah?’ Now he looked outright wary.

‘We’ve said we want to spend our lives together. So. Will you marry me?’

Pause. Paul, hands thrust in pockets, squinted over his coat collar.

‘Are you joking?’

Bad start.

‘No. I, Delia Moss, am asking you, Paul Rafferty, to marry me. Officially and formally.’

Paul looked … discomfited. That was the only word for it.

‘Aren’t I meant to ask you?’

‘Traditionally. But we’re not very traditional, and it’s the twenty-first century. We’re equal. Who made the rules? Why can’t I ask you?’

‘Shouldn’t you have a ring?’

Delia could see a stag-do group approaching over Paul’s shoulder, dressed as Gitmo inmates in orange jumpsuits. They wouldn’t have this privacy for long.

‘I know you don’t like wearing them so I thought I’d let you off that part. I’m going to get a ring though. I might’ve already chosen one. We can be so modern that I’ll pay for it!’

There was a small silence and Delia already knew this was not what she’d hoped or wanted it to be.

Paul stared out over the river. ‘This is a lovely gesture, obviously. It’s just …’

He shrugged.

‘What?’

‘I thought I’d ask you.’

Hmmm. Delia thought the sudden insistence on following chivalrous code was disingenuous. He didn’t like being bounced into it, more like.

She fought the urge to say, sorry if this is too soon for you. But we’ve been getting tipsy on holidays and talking about it happening maybe next year for the last five years. I’m thirty-three. We’re meant to be trying to start a family straight after: on the honeymoon, hopefully. This is our ten-year anniversary. What were you waiting for? When were you waiting for?

She shook the irritation off. The mood was already strained and she didn’t want to shatter it completely with accusations or complaints.

‘You haven’t given me an answer,’ she said, hoping to sound playful.

‘Yeah. Yes. Of course I’ll marry you,’ Paul said. ‘Sorry, I didn’t see this coming at all.’

‘We’re getting married?’ Delia said, smiling.

‘Looks like …?’ Paul said, rolling his eyes, grudgingly returning her smile, and Delia grabbed him. They kissed, a hard quick kiss on the lips of familiarity, and Delia tried to keep still and commit the feeling to memory.

When they moved apart, she said, ‘And I have champagne!’ She knelt and fumbled in her heavy bucket bag for the bottle and the plastic flutes.

‘Here?’ Paul said.

‘Yeah!’ Delia said, looking up, pink with exhilaration, Kingfishers and cold.

‘Nah, come on. We’ll look like a pair of brown-bag street boozers. Ground grumblers.’

‘Or like people who just got engaged.’

A look passed across Paul’s face, and Delia tensed her stomach muscles and refused to let the disappointment in.

Maybe he noticed, because he pulled her up towards him, kissed the top of her head and said into her hair: ‘We can go somewhere that serves champagne and has central heating. That’s my proposal.’

Delia paused. You can’t try to run the whole show. Let him have his way. She took his hand and followed him back down the bridge, arm once more through his, their pace now quicker, thoughts buzzing. Engaged.

Paul had once said to her, about the loss of his parents: you can still choose whether you’re going to be unhappy or not. Even in the face of something so awful, he said he’d started to recover when he realised it was a choice.

‘But what if so many bad things have happened to you, you’re unhappy and it’s not your fault?’ she said.

Paul replied: ‘How many people do you know where that’s the case? They’ve chosen gloom, that’s all. Every day, you get to choose.’

Delia realised two things during that conversation. 1) Part of the reason she loved Paul was his positivity. 2) From then on, she could spot Gloom Choosers. Her office had one or two.

So tonight, Delia thought, she could either dwell on the fact she’d never got a proposal, and that her offer to him instead had been met with some reluctance. That Paul was simply never going to be the kind of man to gaze into her eyes and tell her she set his world alight.

Or she could concentrate on the fact that she was walking hand-in-hand with her new fiancé to a pub in their wonderful home city to drink champagne and chatter about wedding plans, on a stomach full of coconutty curry.

She chose to be happy.

Four

‘They only do champagne by the bottle,’ Paul said, after they burst in to the warmth of the Crown Posada. Paul didn’t drink in places that hadn’t won CAMRA awards. They rubbed their hands and studied the laminated drinks menu as if they were at The Ritz.

‘Shall we bother with the fizz? Booze is booze is booze,’ Paul said.

Delia realised the evening as she’d imagined it wasn’t quite going to happen, but don’t force it, she thought to herself. You have your wedding day planning for all this stuff. (Wedding day planning! It was possible that Delia had a secret Pinterest board, covered with long-sleeved lace dresses and quirky licensed venues in the Newcastle area, and hand-tied bouquets of peonies, paperwhites and roses in ice-cream colours. At last, she could now go legit.)

She acquiesced cheerfully and Paul readied sharp elbows among the crowd to get their usual order, a bottle of Brooklyn Lager for him and a Liefmans raspberry beer for her. Paul sometimes worried they were ageing hipsters.

He motioned for Delia to grab a table and she retreated across the room to watch him waiting his turn at the bar, one eye on the action, the other playing with his phone. Nat King Cole’s ‘These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You)’ was crackling on the Posada’s ancient gramophone, competing with a roomful of lively inebriated conversation.

Paul’s scruffy good looks were even better when offset by something smarter, she thought, like tonight’s fisherman’s coat. She had an idea for a Paul Smith suit, tie and brogue combination for the wedding (the Pinterest board was busy), but she’d have to broach it carefully so Paul didn’t feel emasculated. She wanted him to be completely involved.

She knew the right way to pull him in – interest Paul in the drinks, then the music, and finally, the food.

Think of it as dinner at theirs, writ large, she’d say. Paul and Delia were big on having people to dinner. When Delia had moved into the house in Heaton, she’d been free to indulge all her nesting urges. Paul had invested in the house as a blank canvas, but with no particular idea of what to do with it. He liked that she liked decorating, and a perfect deal was struck.

When other people her age were spending on clothes, clubs and recreational drugs, Delia was saving for a fruit-picker’s ladder she could paint the perfect sailboat blue, or trawling auctions for mirrored armoires that locked with keys that had tassels. She knew she was an old-before-her-time square but when you’re happy, you don’t care.

Delia was also an enthusiastic home cook, and Paul always had wholesaler-size piles of drink from the bar. Thus they were the first among their peers with a welcoming, grown-up house.

Many a Saturday night ended in a loud, messy singalong with their best friends Aled and Gina, with Paul acting as DJ.

In fact, Delia had wondered whether to throw an engagement party. She had recently ordered some original 1970s cookbooks and was enjoying making retro food: scampi with tartare sauce, Black Forest gateau. She fantasised about a kitsch Abigail’s Party buffet.

Should her family come to that do? Delia would wait to call her parents, leave it until tomorrow. She would love to tell them now, to make it more real. But she couldn’t bear the thought that Paul didn’t have an equivalent call to make. Not even to his brother, what with the time difference.

Her phone rippled with a text. Paul. She looked up in surprise. He was playing it cool, pocketing his phone as he gave their order to the bar man.

Delia grinned an idiotic grin, feeling the joy roll through her. Oh ye of little faith. She had her moment. He’d needed time to get used to it, that’s all. There was a romantic in him. She slid the unlock bar, typed her code (her birthday, Paul’s birthday) and read the words.

C. Something’s happened with D and I don’t want you to hear it from anyone else. She’s proposed. Don’t know what to do. Meet tomorrow? P Xx

Delia sat stock still, the weight of the phone heavy in her palm. Suddenly, nothing made sense. She had to work through the discordant information, line by line, as her stomach swung on monkey bars.

‘Don’t know what to do’ punched her in the heart.

Then there were the kisses at the end of the message. Paul was not an electronic kisser. Delia was privileged to get a small one. And she was his closest family.

But what was so frightening was the intimate tone of the message. A voice coming through it that wasn’t Paul’s, or Paul as she knew him.

She spoke sternly to herself. Delia. Stop being wilfully stupid. Add the sum up to its total. This is clearly meant for another woman. The Other Woman.

‘I don’t want you to hear it from anyone else.’ Some faceless, nameless stranger had this size of a stake in their lives? Delia felt as if she was going to throw up.

Paul put the drinks down on the table and dragged the chair out opposite her.

‘I like the ale in here but they need to step the service up. They’ve no rush in them.’ Paul paused, as Delia stared dully at him. ‘You OK?’

She wanted to say something smart, pithy, wounding. Something that would slice the air in two, the same way Paul’s text had just karate-chopped her life into Before and After.

Instead she said, glancing back down at her phone, ‘Who’s C?’

Paul looked at the mobile, then back at Delia’s expression again. He went both red and white at the same time, the colour of a man Delia had once sat next to on a National Express coach who’d had a coronary in the Peaks.

She’d been the only passenger who knew First Aid, so she ended up kneeling in mud at the roadside doing CPR, trying not to retch at tasting his Tennant’s Extra.

She would not be giving Paul mouth-to-mouth.

‘Delia,’ he said, with an agonised expression. It was a sentence that started and stopped. Her name and his voice didn’t sound the same. From now on, everything was going to be different.

Five

Art didn’t prepare you for the smaller moments between the big moments, Delia thought. Life had no editing suite to shape the narrative into something that flowed.

If the arrival of Paul’s text had happened onscreen, after the close-up of Delia’s horrified face there’d have been a jump cut to her bowling away down the street, stumbling on her heels (rom com), slinging plates around their kitchen (soap opera), angrily filling a battered clasp-lock suitcase (music video), or staring out across the blustery Tyne (art house).

Instead, what happened next undercut the momentous awfulness with boring practicality.

It was established in words of few syllables that Paul had sent the message to the person it was about, rather than the person it was for. A fairly common cock-up that usually had less dramatic impact. There was a surreal moment when a wild-eyed Paul rambled about only sending it to Delia the second time when he thought it hadn’t sent, or something. As if that could make it better and it could somehow be un-seen.

It begged a lot of other questions and answers, ones they could no longer exchange in a busy pub.

Delia managed to quell her urge to vomit. Then she had to get home.

While she considered leaving Paul on his own, looking at two full glasses and a swinging pub door, he’d only follow her. If she succeeded in storming solo into a taxi, all she’d do at home was wait to confront him anyway. It seemed a self-defeating gesture of defiance that would achieve nothing more than a double cab fare.

So she had to endure a silent, agonising journey in a Hackney, pressed against the opposite side of the seat from Paul, staring through the smudged window, occasionally catching the curious face of the driver in his rearview mirror.

When she put her key in the door, there was the familiar bump, scrape and snuffle of their dog Parsnip on the other side. Paul, obviously glad of the distraction, shushed and petted him, making Delia want to scream: Don’t be nice to the dog, you huge bastard faker of niceness.

Parsnip was a tatty old incontinent Labrador-Spaniel cross they’d got from a rescue centre, seven years ago.

‘We can’t place this one, he pisses,’ the man had told them, as they stroked the sad, googly eyed, snaggle-toothed Parsnip. ‘Could that be because you tell people he pisses?’ Paul said. ‘We have to,’ the man replied. ‘Otherwise you’ll just bring him back. His name should be Boomerang, not Parsnip.’

‘No bladder control and named after a root vegetable. Poor sod,’ Paul said, and sighed, looking at Delia. ‘I think he’s coming home with us, isn’t he?’

And right there was why Delia fell in love with Paul. Funny, kind, Paul, who understood the underdog – and was sleeping with someone else.

Delia pulled her clanking work bag from her shoulder and dropped onto the leather sofa, the oxblood Chesterfield she’d once spent all day pecking at an eBay auction to win. She didn’t have the will to take her coat off. Paul threw his on the arm of the sofa.

He asked her in hushed tones if she wanted a drink, and again she felt like she hadn’t been given a copy of the script.

Should she start screaming now? Later? Was the drink offer outrageous, should she tell him he couldn’t have one? She simply shook her head, and heard the opening of cupboards, the plink of the glass on the worktop, the clink of the bottle. The glug of … whisky? She could tell Paul took a hard swig before he re-entered the room.

He sat down heavily on the frayed yellow velvet sofa, at a right angle to where she was sitting.

‘Say something, Dee.’ He sounded gratifyingly shaky.

‘What am I supposed to say? And don’t call me Dee.’

Silence. Apart from the clatter of Parsnip’s unclipped toenails on tiles, as he skittered back from the kitchen and settled into his basket in the hallway.

She was expected to open this conversation?

‘How did it start?’

Paul stared at the fireplace. ‘She came into the bar one night.’

The same way I did, Delia thought.

‘When?’

‘About three months ago.’

‘And?’

‘We got chatting.’

There was a pause. Paul had a cardiac arrest pallor again. It looked as if giving this account was as bad as the original discovery. Good.

‘You got chatting, and next thing you know, your penis is inside her?’

‘I never meant for this to happen, Dee … Delia. It’s like some nightmare alternate reality. I can’t believe it myself.’

‘How did you end up shagging her?!’ Delia screamed and Paul almost started with fright. Offstage, Parsnip gave a small squeak. Paul put his glass down with a bump, and his palms together in his lap.

‘She kept coming in. We flirted. Then there was a Friday lock-in, with her friends. She came and found me when I was bottling up. I knew she liked me but … it was a total shock.’

‘You had sex with her in the store cupboard?’

‘No!’

‘You did, didn’t you?’

‘No, I absolutely didn’t,’ Paul said, without quite enough conviction, shaking his head. Delia knew the answer he wouldn’t give: not full sex. But more than a kiss. What Ann called mucky fumbles.

‘What’s her name?’

‘Celine.’

A sexy name. A cool name. Celine created visions of some bobbed, Gitane-smoking Left Bank beauty in black cigarette pants.

Oh God, this hurt. A fresh wound every time, as if she was being whipped by someone who knew exactly how long to leave the sting to burn before lashing again.

‘She’s French?’

‘No …’ He met her eyes. ‘Her mum likes Celine Dion.’

If Paul thought he could risk cute ‘you’d like her, you’d be friends’ touches, with information that had come from pillow talk, Delia feared she’d get violent towards him.

‘How old is she?’

Paul dropped his eyes again. ‘She’s twenty-four.’

‘Twenty-four?! That’s pathetic.’ Delia had never disliked her own age, but now she boiled with insecurity at the twenty-fourness of being twenty-four, compared to her woolly old thirty-three. She’d never worried that men liked younger women, and yet here they were, living the cliché.

Twenty-four. One year older than Delia had been when she met Paul. He’d traded her in. Ten-year anniversary – time to find someone ten years younger.

‘How many times have you had sex?’

Delia had never wondered if she was the kind of person who’d want to know nothing, or everything, when in this situation. Turned out, it was everything.

‘I don’t know.’

‘So many you’ve lost track?’

‘I didn’t keep count.’

‘Same thing.’

A pause. So much sex Paul couldn’t quantify it. She could probably tell him how many times they’d slept together this year, if she thought about it.

‘Where did you have sex with her?’

‘Her house. Jesmond. She’s a mature student.’

Delia could picture it; she’d lived there as a student too. Lightbulb twisted with one of those metallic Habitat garlands that looked like a cloud of silvered butterflies. Crimson chilli fairy lights draped like a necklace across the headboard. Ikea duvet. Bare bodies underneath it, giggling. Groaning. She felt sick again.

‘How did you hide it? I mean, where did I think you were?’

To have had no idea was genuinely startling. She’d always been so proud of the trust between her and Paul. ‘All that opportunity, aren’t you ever worried?’ some women used to say. And she’d laugh. Not in the slightest. Cheating wasn’t something they did.

‘I’ve been leaving work earlier some nights. Delia, please, can we …’ Paul put his face in his hands. Hands that had been in places she’d never imagined.

She looked down at her special anniversary dress with the dragonflies. She and Paul shared a home, a wavelength, a pet, a past. They were always honest, or so she thought. Any passing fancies on either side were running jokes between them, and could be admitted in the safety of knowing there was no real risk. There was leeway, trust, a long leash. Paul and Delia. Delia and Paul. People aspired to have what they had.

‘What’s she like in bed?’ Delia said.

‘Can we not …?’

‘Can we not be having this awkward conversation about all the times you’ve had sex with someone else? That relied on you, not me, didn’t it?’

She felt as if Paul had let an intruder into their lives, a third person into their bed. It was a total, bewildering, senseless betrayal from the one person she was supposed to be able to count on. Why? She didn’t want to question herself – it was Paul who should face interrogation – but she couldn’t help it.

Would it have been different if I’d been different? Made you feel less secure? Lost a stone? Gone out more? Gone on top more often?