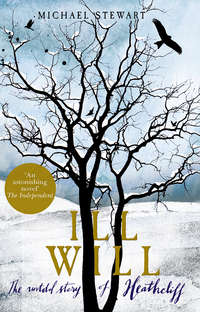

Ill Will

I went back to the marketplace. More people were milling about now and it was easier this time to steal another apple and a chunk of bread. I stole a wheel of cheese and a meat pie, put them in my pockets. I climbed to the hill above the town. The sun was still in the east and I needed to walk west as that was the direction of Manchester. I just needed to keep the sun behind me until noon, then keep the sun in front of me till dusk. I could see Lumbutts Farm in the distance. I made my way across moor, through Bird Bank Wood and Old Royd. And eventually into the village of Todmorden. The road followed the river, where the houses were built into the steep clough, which climbed high on both sides. The effect of this was to make the way ahead darker than the way back. Parts of the clough were quarried and there were heaps of stones waiting to be faced at the mouths of the delves. I needed money and lodgings. I was far enough away now from Wuthering Heights. Although I’d walked here by myself before, when you were laid up at the Lintons’, I knew that it was far enough away from Wuthering Heights that I’d not be spotted here. Joseph said the men who lived hereabouts had hairs on their foreheads and the women had webbed feet, but I suspected that was just idle laiking. I could ask for work. Summer. Plenty of farm labour. It was midday when I arrived in the village. I sat down by the green. I ate the pie. First the crust, then the filling. I wandered around until I found a tavern on the corner of a cobbled street. There was a sign outside that I could not read, but the painting on the sign was of a jolly fellow in a bright smock, and the place looked friendly enough. After some deliberation, I plucked up the guts to go inside.

It was dark and smelled of stale beer, colder inside than out. There was a fireplace but no fire, it being the wrong time of year for flames. I marked the stone floor and the low wood beams, the wooden benches and seats. A few farmers were standing around a horn and rope, playing ring-the-bull. A group of labourers were leaning on the bar. I asked them to excuse me as I made my way to the barrels. They were in no rush to move but shuffled out of the way nevertheless.

‘What can I get you?’ said the landlord. A large, ruddy-faced man with ginger whiskers. He was standing by a massive barrel of ale, laid on its side, with a tap at one end. I had no money.

‘I’m looking for work.’

‘You what?’

‘I want a job.’

‘Round here?’

‘Or hereabouts. I’m a hard worker. I don’t shirk. I can do any amount of farm work: digging and stone-breaking, wall-building, graving, tending foul. Whatever there is I can turn my hand to it. Do you have work yourself? Cellar work, maybe? I can lift barrels all day.’

‘No. No work here, pal.’

‘Would you mind if I asked your customers?’

‘What do you think this is? Either buy some ale or fuck off.’

I looked around the room. At the hostile faces, white faces. White faces looking me up and down. I didn’t fit, wasn’t welcome. I looked at the labourers and saw the muck on their knuckles like ash keys. I looked at the farmers and saw the mud on their boots. Yes, there was work hereabouts, but not for me, Cathy. Turn around. Get out.

I wandered around the village. Not much to see. There were signs of life all right. But no life for me. I made my way to the river. If I followed its flow, it would take me in the right direction. There was a faint path by its banks, more of a rabbit run, or a badger track. I carried on walking, at the edge of what I knew. I’d never been further than this point. Not since I was a small boy, in any case, when I was taken from one place to another, then to somewhere else to be abandoned at the dockside. My memory of my early life was like a landscape shrouded in a thick mist. I remembered streets near water. I remembered rowing boats and ships with massive sails. I remembered a warm room full of strong smells and harsh sounds, a strange man with a knife, beckoning me. He was smiling at me but something about him was unsettling. He smelled of grease and sweat and his teeth were black. There were many shiny surfaces but everything else was a blur. I didn’t even have a clear memory of Mr Earnshaw. The first thing I remember clearly is you, Cathy. I remember our first meeting, and our friendship growing stronger each day. Until it grew beyond friendship into something else. I remember the first time we fucked, and after, lay in each other’s arms, looking up at the sky, watching the clouds form into faces. Counting crows. Joseph was out, loading lime past Penistone Crags. Hindley was on business. When we got back home, I marked the occasion in the almanac on the wall. A cross for every night you spent at the Lintons’. A dot for those times spent with me on the moor. I showed you the almanac. You said that you found me dull company. You said I knew nothing and said nothing. You said I stank of the stable. Then Edgar turned up, dressed in a fancy waistcoat and a high-topped beaver hat. I left you to your pretty boy.

As I followed the beck west, I dreamed as dark as the brackish waters. I wanted to kill them all, but like a cat with a bird, leave them half-killed, so I could come back later, again and again, to torment them. You as well, Cathy. You were not exempt from my plans. The sun was directly above me now and I could feel its heat. I took off my coat and bent down low so that I could cup some water from the beck. I saw my black reflection staring back. I took a drink. It cooled me. I sat by the bank and brooded. I watched water boatmen and pond skaters dance across the surface of the beck where it gathered and pooled. I watched beetles dive for food and gudgeon gulp. Blue titmouse and great titmouse flittered in the branches above. I watched a shrike impale a shrew on the lance of a thorn. I didn’t know how long it would take me to get to Manchester. Another day or two, perhaps. Surely there would be work there for a blackamoor. I’d heard we were more common in those parts. I stripped off and dived into the beck, washing all the filth from my body. The water was cool at first but as I swam, it soon warmed around me. My flesh tingled and my skin tightened. I splashed water on my face and rubbed at the mud in my hair. I lay back, let the water take my weight, and looked up at the sky. I floated like that, staring up at the white whirl of clouds, with no thought in my head. The clouds drifted, gulls flew by. I closed my eyes and tried to keep my mind as clear as the sky, pushing out all thoughts.

Across the blank blue of my mind I heard a voice: There’s money to be made in Manchester town. And I remembered Mr Earnshaw say that a man from humble stock could make a pretty penny in the mills and down the mines. And I heard your voice, Cathy. That it would degrade you to marry a man as low as me. Oh, I’d get money all right. I’d show you. I’d shame you. Words that burned. Words as sharp as swords. Words you could only say behind my back. I’d shove those ugly words down your lovely throat.

I swam to the bank and climbed out. I sat by the edge of the water and watched toad-polls flit by the duckweed and butterflies flap by Rock Rose. A butterfly and a frog. They both had two lives. Why couldn’t I have two lives? Like that toad-poll at the edge of the beck, already sprouting legs, about to break through the film of one world into another, I was on the cusp of the life that had been and the life that could be. I could rise from the depths. I could crawl into the light.

I lay naked as a newborn and listened to rooks croak and whaaps shriek. I let the sun and the breeze dry my skin, then I got dressed. I stuck my hands deep in my pockets, retrieved the rest of the pilfered vittles, just crusts and crumbs, and scoffed the lot. I lay back on the cool grass to rest for a minute or two. I watched twite and snipe, grouse and goose. I didn’t want to think about you or them but it seemed that my mind was set on its course. I couldn’t stop it thinking about them and you. What they had done. What they had not done. What you had done. What you had not done. It would degrade you. I would degrade you.

I watched the peewit flap their ragged wings and listened to their constant complaining, tumbling so low as to almost bash their heads on the bare earth. Perhaps they had young nearby and were warning me away.

Out here, surrounded by heather and gorse, with the blue sky above me, I felt free. I closed my eyes and felt the sun’s rays on my face. The sun felt like you. Like your heat next to my skin. Like your breath on my neck.

When I woke the sun was further on. I felt dozy. Must keep going. I got up and shook the grass from my clothes. I plucked cleavers from my breeches. I stretched my limbs and joined the path by the river once more. I walked through fields of sheep, fields of wheat, fields of beef. Fields of milk, mutton and mare. Over meadow, mire and moor. I climbed over dry-stone walls. And clambered through forest. Eventually I approached another village. I arrived at a packhorse track and walked along it. I passed cottages and barns. Mistals and middens. There was a sign on the road but I couldn’t read it. Although I knew the alphabet, you never completed your tutelage. There was always something in the way with language. We had a more direct connection, Cathy. A pure link. That’s what you said, and I believed you.

It was a small village with two taverns, a butcher’s, a baker’s and a chapel. All clustered around a green where a tethered goat grazed. I went into the first pub and asked for work. I went into the second pub and asked for work, and in every shop. Everywhere I enquired the answer was the same: no work for the likes of you. My limbs ached. My eyes felt as though they were full of sand. I sat on a bench in the graveyard. I was tired and it would be dusk soon. No roof to offer me shelter. I sat and watched two old women tend to a grave. They pulled out weeds and arranged some flowers. They scraped away the lichen from the engraving so that the chiselled letters were fresh once more. They nattered and gabbed. So-and-so has his eye on so-and-so. Will he do right by her or will he use her as his plaything? Looks Spanish. When’s summer going to start proper? Who was that strange fella in church last Sunday? Not seen him before. Not from these parts. Old Mr Hargreaves is dead. Finest weaver in the county. Found him in his own bed. Half-undressed. On and on they nattered, about this and that. By these women was an open grave.

The women noticed that I was watching them. They looked at me suspiciously. They pointed and whispered. But I didn’t care. Let them talk. Let them think and say what they liked. They meant nothing to me. There was no one alive who meant anything to me now. Not even you, Cathy. I was nothing, and no one. I focused instead on the black rectangle to the side of the women. Its blackness falling down into the ground. Where did it go, this blackness? To hell? Perhaps I should climb into this hole. I thought back to Joseph’s fire-and-brimstone catechisms. Was hell really all as bad as he would have it? With sinners in perpetual torment? You showed me a picture in a book, Cathy. A man with horns and a pitchfork and a big grin on his pointy face. He looked more comical than evil. Evil hides behind the door. It lurks in the shadows. As I thought about hell and evil, I saw people congregate. There were men and women gathering around the black rectangle. There were four men carrying a coffin on their shoulders. They were dressed in black and the men and women surrounding the hole were dressed in black. A veiled woman was crying. I could see her face shake beneath the veil and tears fall onto her dress. It was good to watch her cry and watch the rest of them grieve. Let her weep in her widow’s weeds. It was music and food to me.

I thought about her wedding to this corpse who had once been a man. Perhaps in this very church. Everyone done up again, only this time in white and brightly coloured garments, the lavish pretence, the gilded facade. Pretending to marry for love, when really it was for wealth and status. Love didn’t need a marriage chain or a poncey parade. Love baulks at ceremony and licence. They talk about tying the knot but love unties binds. It lets the bird out of the cage. The bird that is freed flies highest. The cage is best remembered enveloped in flames.

You told me you would never get married. That we would always be together. You promised. How easily your words betray you. Marriage is for dull people, we both agreed. And people are dull, except for when they grieve. I watched the priest and the party of mourners, watched the mound of earth at the back writhing with worms, starlings stabbing at the flesh. I watched the men drop the coffin, using ropes to lower it slowly into blackness. More people weeping. Some of them beyond tears. I supped on their misery. Every death is a good death. All flesh is dead meat. I had cried when Mr Earnshaw passed away, but now I wished I hadn’t. I was glad I’d listened to his last breath. Seen him choke. Will he go to hell or to the other place? I hoped he would burn and his blood would boil in the red flames of the inferno. I cursed cures and blessed agues. At last the wooden box was lowered into the ground completely and the ropes thrown in after it. Swallowed up by blackness. How long would the fine oak casket last until the wood splintered and decayed, and all the slimy things ate beneath the grave?

When all of the party had gone back the way they came, with heads bowed and handkerchiefs on display, I stood up and approached the open grave. I stood over the black hole and peered in. The coffin was surrounded by clay, with black soil on top of the box, which the pastor had chucked in. I imagined, in the place of the coffin, you and I, Cathy, lying next to each other. With six feet of earth above our heads. For all eternity. That way you would keep your promise.

I left the churchyard and wandered around the village and the looming moorland until it was fully dark. I was looking for shelter. I came across a farm surrounded by outbuildings. I found an unlocked barn, lifted the latch and swung open the door. Inside there were pigs, nudging and jostling each other. They smelled of their own shit. In the corner, by the swine, was some loose straw. It wasn’t exactly a four-poster bed but I could make my rest out of that, I thought.

I left the barn and wandered some more, not tired enough to lie down on God’s cold earth. I walked down a tree-lined track, back into the village. As I did, I heard music in the distance, a cheerful jig, and, drawn to the noise as a moth is to a lantern, I tried to find its source. I wandered along cobbled roads and muck tracks until I came to a village hall. It was a large barn, painted white, with light pouring from its windows. The music was coming from inside. I walked around the back. There was a small leaded window and I peered in. There were lines of lanterns and a huge fireplace with a roaring fire. There was a long table laid with food and drink. There were people lined up dancing: men and women of all ages. The women wore colourful frocks and bonnets. The men wore smart breeches, bright waistcoats and fancy hats. The hall was decorated with brightly coloured ribbons. There was a fiddle player in a cocked hat, playing a frenetic tune. I watched the group dance and sing and sup flagons of ale. I watched them smile and laugh and talk excitedly. The men held their women in their arms and drew them close to their bodies. I felt sick at the sight of them.

Then I saw a black, repulsive face staring back at me. Half-man, half-monster, just as Hindley said. My reflection in the glass pane. A black shadow of a man with not a friend in the world nor a bed to rest, barred from life’s feast. I wanted the night sky to swallow me up, to be dust. I could never be one of those people in there. My life would never be one of mead and merriment. Condemned to stand outside the party. Not like you, Cathy, with your fancy frocks and fancier friends. With your ribbons and curls and perfumes. I wandered back to the farm, crept into the animal barn, and lay down on the straw with the swine.

Flesh for the Devil

That night I dreamed we were on the moor; the heather was blooming, and you were teaching me the names of all the plants of the land: dog rose, gout weed, earth nut, fool’s parsley, goat’s beard, ox-tongue, snake weed. Your words were like a spell. I watched your lips form the sounds. I saw your tongue flit between your perfect teeth. Witches’ butter, bark rag, butcher’s broom, creeping Jenny, mandrake. We looked around at the open moorland, but it had all been hedged and fenced and walled. There were men, hundreds of them, burning the heather, digging ditches, breaking rocks. There were puritans, Baptists, Quakers, inventors, ironmasters, instrument-makers. Our place had been defiled. The flowers of the moor had been trampled on. The newborn leverets butchered. The mottled infant chicks of the peewit had been crushed underfoot. Guts in the mud. You were in the middle of the mob, a heckling throng, staring around. I held my hand out but I couldn’t reach you. You were lost to me.

The next thing I was aware of was someone taking me by the shoulders.

‘What the bloody hell do you think you’re doing?’

I was in the barn with the swine, and a lump of a man with a bald head was shaking me roughly. He wore big black boots and a leather jerkin. He looked more like an ogre than a man. It was morning and light from the open barn door poured in.

‘I’m sorry, sir.’

I was too weak from sleep to fight the brute.

‘What do you think this is, a doss-house?’

‘I had nowhere to stay,’ I said.

‘That’s no excuse.’

‘I was tired,’ I said.

‘Get up and get out. This isn’t a hostel for gypsies.’

‘I’m no kettle-mender.’

‘What’s your name?’

I thought for a moment; I wracked my brains.

‘Come on then, lad, speak up. Have the hogs gobbled your tongue?’

I remembered that young boy at chapel, Cathy, you were friendly with him. Died of consumption a few years since. I always liked his name. It was good and whole and clean.

‘My name, sir, is William Lee.’

I’d stolen the name of a dead child. A boy we laiked with before and after sermon.

‘Well then, William, Will, Billy, that doesn’t sound gypsy to me, I give you that. What kind of work can you do?’

‘I can dig, build walls, tend fowl, tend swine. Any work you have.’

‘Are you of this parish?’

‘I’m an offcumden, sir, from the next parish.’

‘I do need hands, as it happens.’

‘What for?’

‘I’ve a wall that needs building. And stone that needs breaking. A bloke did a flit after a drunken brawl a few nights back. I’m a man down.’

‘I’m that man, sir. I’m a grafter.’

‘Sure you’re not a pikey?’

‘I’m sure.’

‘I don’t employ gyppos.’

He took me over three fields, two of meadow, one of pasture, to where there was a birch wood and a small quarry. As we stood by the delph I realised, in fact, that he wasn’t as large as I’d at first thought. Though still heavyset and big of bone, he was not the giant my waking eyes had taken him for.

‘This is where you get the stone. There’s a barrow there. Don’t over-fill it, mind. I don’t want it splitting.’

He showed me where it had been parked for the night. Next to the barrow were several picks and wedges, as well as hammer and chisel. Then he walked me across to another field where a wall was partly constructed.

‘And this is the wall. In another hour or so there will be some men to join you. Some men to break stone and others to build. The one they call Sticks will tell you what to do.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

‘The name’s Dan Taylor. I own this farm.’

With that the farmer walked back down to the farm buildings and I sat on a rock. I amused myself by pulling grass stalks from their skins and sucking on the ends. I gathered a fist of stones and aimed them at the barrow. I watched the tender trunks of the birch wrapped in white paper. A web of dark branches. The leaves and the catkins rustled in the breeze. I waited an hour or two before the first of the men arrived. He was skinny as a beanpole and his hair was dark. He had a bald patch to the side just above his ear, in the shape of a heart. His beard grew sparsely around his chops. He told me the farmer had spoken to him about me.

‘Well, William Lee, you do as you’re told and we’ll get along fine, laa. The name’s John Stanley. Everyone calls me Sticks.’

He unfurled his arms the way a heron stretches out its wings and offered me his willowy hand to shake.

We broke stone for a time before two more men appeared and joined us. When we were joined by another two men, Sticks put his pick down.

‘Right, men, we’re all here and there’s lots to do. Looks like the weather will hold out despite the clouds.’

He pointed up. There were patches of blue but mostly the sky consisted of clouds the colour of a throstle’s egg. Not storm clouds though.

‘Good graftin’ weather,’ one of the men said.

‘This is William Lee. He’ll be working with us today. Me, William and Jethro will work here to begin. Jed, you barrow, and you two start walling. We’ll swap after a time. Come ’ed.’

We set to work again.

‘You from round here then, laa?’ Sticks said as he loaded up a barrow with freshly broken stones.

‘The next parish. About thirty miles east.’

‘So what brings you to this parish then?’

‘I’m just drifting. No particular reason.’

‘People don’t just drift. They always have a purpose. You’re either travelling to somewhere or running away from someone. Which is it?’

‘Neither.’

‘Suit yourself. Give me a hand with this.’

I helped him lift a large coping stone.

‘Had a southerner here last week. From Sheffield. Think he found us a bit uncouth. Only lasted two days. Could hardly tell a word he said, his accent was that strong.’

‘You don’t sound like you’re from round these parts yourself,’ I said.

He had a strange accent and not a bit like a Calder one. He had a fast way of talking and a range of rising and falling tones that gave his speech a distinctive sound.

‘You travel around and you take your chances. I’ve done it myself. Got turned out of one village one time. The villagers threw stones at me and called me a foreigner. It’s getting harder and harder for the working man to make a living.’

‘Why’s that then?’

‘Because a bunch of aristocrats are stealing the land beneath our feet. They’ll turn us all into cottars and squatters. Before you know it there won’t be any working men, just beggars and vagrants, thieves and highwaymen, prostitutes and parasites. Mark my words, laa.’

‘Is that so?’

‘The days of farm work is coming to an end. They’ve got Jennies now across the land that can spin eighty times what a woman can spin on her tod. A lot of the labourers hereabouts have gone off over to Manchester, doing mill work, building canals. I’ve done canal work myself, built up the banks, worked on the puddling. Dug out the foundations. It’s back-breaking work, I’ll tell you that. It’s said that on the duke’s canal the boats can travel up to ten miles an hour. And not a highwayman to be seen. Done dock work as well, in Liverpool. That’s where I’m from, you see, laa.’

I liked the way he pronounced ‘Liverpool’, lumping it up and dragging it out.

I thought about where I had come from. All that I knew was that Mr Earnshaw found me on the streets of that same town. Perhaps I would go back there. Seek out my fortune in that place instead. I wasn’t fixed. No roots bound me to the spot. Where there was money to be made that’s where I was heading. Enough money to get you and Hindley. If I were to make the journey, I could use Sticks’s know-how.

‘I’m heading that way myself,’ I said.

‘Be careful how you go, laa. It’s not safe to walk the roads. A man’s liable to be picked up by a press gang or else kidnapped and sent to the plantations. They’re building big mills over in Manchester. But you won’t get me going there. Worse than the workhouse. Have you heard of the men of Tyre?’