Flyaway

‘Does she know he’s gone?’

‘I don’t know how she can, unless the police told her. I don’t know her address but she lives in London.’

‘I’ll ask them,’ I said. ‘Did Mr Billson have any girl-friends?’

‘Oh no, sir.’ She shook her head. ‘The problem is, you see, who’d want to marry him? Not that there’s anything wrong with him,’ she added hastily. ‘But he just didn’t seem to appeal to the ladies, sir.’

As I walked to the police station I turned that one over. It seemed very much like an epitaph.

Sergeant Kaye was not too perturbed. ‘For a man to take it into his head to walk away isn’t an offence,’ he said. ‘If he was a child of six it would be different and we’d be pulling out all the stops, but Billson is a grown man.’ He groped for an analogy. ‘It’s as if you were to say that you feel sorry for him because he’s an orphan, if you take my meaning.’

‘He may be a grown man,’ I said. ‘But from what I hear he may not be all there.’

‘I don’t know,’ said Kaye. ‘He held down a good job at Franklin Engineering for good pay. It takes more than a half-wit to do that. And he took good care of his money before he walked out and when he walked out.’

‘Tell me more.’

‘Well, he saved a lot. He kept his current account steady at about the level of a month’s salary and he had nearly £12,000 on deposit. He cleared the lot out last Tuesday morning as soon as the bank opened.’

‘Well, I’m damned! But wait a minute, Sergeant; it needs seven days’ notice to withdraw deposits.’

Kaye smiled. ‘Not if you’ve been a good, undemanding customer for a dozen or more years and then suddenly put the arm on your bank manager.’ He unsealed the founts of his wisdom. ‘Men walk out on things for a lot of reasons. Some want to get away from a woman and some are running towards one. Some get plain tired of the way they’re living and just cut out without any fuss. If we had to put on a full scale investigation every time it happened we’d have our hands full of nothing else, and the yobbos we’re supposed to be hammering would be laughing fit to bust. It isn’t as though he’s committed an offence, is it?’

‘I wouldn’t know. What does the Special Branch say?’

‘The cloak-and-dagger boys?’ Kaye’s voice was tinged with contempt ‘They reckon he’s clean—and I reckon they’re right.’

‘I suppose you’ve checked the hospitals.’

‘Those in the area. That’s routine.’

‘He has a sister—does she know?’

‘A half-sister,’ he said. ‘She was here last week. She seemed a level-headed woman—she didn’t create all that much fuss.’

‘I’d be glad of her address.’

He scribbled on a note-pad and tore off the sheet. As I put it into my wallet I said, ‘And you won’t forget the scrapbook?’

‘I’ll put it in the file,’ said Kaye patiently. I could see he didn’t attach much significance to it.

I had a late lunch and then phoned Joyce at the office. ‘I won’t be coming in,’ I said. ‘Is there anything I ought to know?’

‘Mrs Stafford asked me to tell you she won’t be in this evening.’ Joyce’s voice was suspiciously cool and even.

I hoped I kept my irritation from showing. I was becoming pretty damned tired of going home to an empty house. ‘All right; I have a job for you. All the Sunday newspapers for November 2nd. Extract anything that refers to a man called Billson. Try the national press first and, if Luton has a Sunday paper, that as well. If you draw a blank try all the dailies for the previous week. I want it on my desk tomorrow.’

‘That’s a punishment drill.’

‘Get someone to help if you must. And tell Mr Malleson I’ll meet him at four o’clock at the Inter-City Building for the board meeting.’

THREE

I don’t know if I liked Brinton or not; he was a hard man to get to know. His social life was minimal and, considered objectively, he was just a money-making machine and a very effective one. He didn’t seem to reason like other men; he would listen to arguments for and against a project, offered by the lawyers and accountants he hired by the regiment, and then he would make a decision. Often the decision would have nothing to do with what he had been told, or perhaps he could see patterns no one else saw. At any rate some of his exploits had been startlingly like a magician pulling a rabbit out of a hat. Hindsight would show that what he had done was logically sound, but only he had the foresight and that was what made him rich.

When Charlie Malleson and I put together the outfit that later became Stafford Security Consultants Ltd we ran into the usual trouble which afflicts the small firm trying to become a big firm—a hell of a lot of opportunities going begging for lack of finance. Lord Brinton came to the rescue with a sizeable injection of funds for which he took twenty-five per cent of our shares. In return we took over the security of the Brinton empire.

I was a little worried when the deal was going through because of Brinton’s reputation as a hot-shot operator. I put it to him firmly that this was going to be a legitimate operation and that our business was solely security and not the other side of the coin, industrial espionage. He smiled slightly, said he respected my integrity, and that I was to run the firm as I pleased.

He kept to that, too, and never interfered, although his bright young whiz-kids would sometimes suggest that we cut a few corners. They didn’t come back after I referred them to Brinton.

Industrial espionage is a social disease something akin to VD. Nobody minds admitting to protecting against it, but no one will admit to doing it. I always suspected that Brinton was in it up to his neck as much as any other ruthless financial son-of-a-bitch, and I used the firm’s facilities to do a bit of snooping. I was right; he employed a couple of other firms from time to time to do his ferreting. That was all right with me as long as he didn’t ask me to do it, but sooner or later he was going to try it on one of our other clients and then he was going to be hammered, twenty-five per cent shareholder or not. So far it hadn’t happened.

I arrived a little early for the meeting and found him in his office high above the City. It wasn’t very much bigger than a ballroom and one entire wall was of glass so that he could look over his stamping ground. There wasn’t a desk in sight; he employed other men to sit behind desks.

He heaved himself creakily out of an armchair. ‘Good to see you, Max. Look what I’ve gotten here.’

He had a new toy, an open fire burning merrily in a fireplace big enough to roast an ox. ‘Central heating is all very well,’ he said. ‘But there’s nothing like a good blaze to warm old bones like mine. It’s like something else alive in the room—it keeps me company and doesn’t talk back.’

I looked at the fireplace full of soft coal. ‘Aren’t you violating the smokeless zone laws?’

He shook his head. ‘There’s an electrostatic precipitator built into the chimney. No smoke gets out.’

I had to smile. When Brinton did anything he did it in style. It was another example of the way he thought. You want a fire with no smoke? All right, install a multi-thousand pound gadget to get rid of it. And it wouldn’t cost him too much; he owned the factory which made the things and I suppose it would find its way on to the company books under the heading of ‘Research and Development—Testing the Product’.

‘Drink?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘The working day seems to be over.’

He pressed a button next to the fireplace and a bar unfolded from nowhere. His seamed old face broke into an urchin grin. ‘Don’t you consider the board meeting to be work?’

‘It’s playtime.’

He poured a measured amount of Talisker into a glass, added an equal amount of Malvern water, and brought it over to me. ‘Yes, I’ve never regretted the money I put into your firm.’

‘Glad to hear it.’ I sipped the whisky.

‘Did you make a profit this year?’

I grinned. ‘You’ll have to ask Charlie. He juggles the figures and cooks the books.’ I knew to a penny how much we’d made, but old Brinton seemed to like a bit of jocularity mixed into his business.

He looked over my shoulder. ‘Here he is now. I’ll know very soon if I have something to supplement my old age pension.’

Charlie accepted a drink and we got down to it with Charlie spouting terms like amortization, discounted cash flow, yield and all the jargon you read in the back pages of a newspaper. He doubled as company secretary and accountant, our policy being to keep down overheads, and he owned a slice of the firm which made him properly miserly and disinclined to build any administrative empires which did not add to profits.

It seemed we’d had a good year and I’d be able to feed the wolf at the door on caviare and champagne. We discussed future plans for expansion and the possibility of going into Europe under EEC rules. Finally we came to ‘Any Other Business’ and I began to think of going home.

Brinton had his hands on the table and seemed intent on studying the liver spots. He said, ‘There is one cloud in the sky for you gentlemen. I’m having trouble with Andrew McGovern.’

Charlie raised his eyebrows. ‘The Whensley Group?’

‘That’s it,’ said Brinton. ‘Sir Andrew McGovern—Chairman of the Whensley Group.’

The Whensley Group of companies was quite a big chunk of Brinton’s holdings. At that moment I couldn’t remember off-hand whether he held a controlling interest or not. I said, ‘What’s the trouble?’

‘Andrew McGovern reckons his security system is costing too much. He says he can do it cheaper himself.’

I smiled sourly at Charlie. ‘If he does it any cheaper it’ll be no bloody good. You can’t cut corners on that sort of thing, and it’s a job for experts who know what they’re doing. If he tries it himself he’ll fall flat on his face.’

‘I know all that,’ said Brinton, still looking down at his hands. ‘But I’m under some pressure.’

‘It’s five per cent of our business,’ said Charlie. ‘I wouldn’t want to lose it.’

Brinton looked up. ‘I don’t think you will lose it—permanently.’

‘You mean you’re going to let McGovern have his way?’ asked Charlie.

Brinton smiled but there was no humour in his face. ‘I’m going to let him have the rope he wants—but sooner than he expects it. He can have the responsibility for his own security from the end of the month.’

‘Hey!’ I said. ‘That’s only ten days’ time.’

‘Precisely.’ Brinton tapped his finger on the table. ‘We’ll see how good a job he does at short notice. And then, in a little while, I’ll jerk in the rope and see if he’s got his neck in the noose.’

I said, ‘If his security is to remain as good as it is now he’ll have to pay more. It’s a specialized field and good men are thin on the ground. If he can find them he’ll have to pay well. But he won’t find them—I’m running into that kind of trouble already in the expansion programme, and I know what I’m looking for and he doesn’t. So his security is going to suffer; there’ll be holes in it big enough to march a battalion of industrial spies through.’

‘Just so,’ said Brinton. ‘I know you test your security from time to time.’

‘It’s essential,’ I said. ‘We’re always doing dry runs to test the defences.’

‘I know.’ Brinton grinned maliciously. ‘In three months I’m going to have a security firm—not yours—run an operation against McGovern’s defences and we’ll see if his neck is stuck out far enough to be chopped at.’

Charlie said, ‘You mean you’re going to behead him as well as hanging him?’ He wasn’t smiling.

‘We might throw in the drawing and quartering bit, too. I’m getting a mite tired of Andrew McGovern. You’ll get your business back, and maybe a bit more.’

‘I hope you’re right,’ said Charlie. ‘The Whensley Group account is only five per cent of our gross but it’s a damned sight more than that of our profits. Our overheads won’t go down all that much, you know. It might put a crimp in our expansion plans.’

‘You’ll be all right,’ said Brinton. ‘I promise.’ And with that we had to be satisfied. If a client doesn’t want your business you can’t ram it down his throat.

Charlie made his excuses and left, but Brinton detained me for a moment. He took me by the arm and led me to the fireplace where he stood warming his hands. ‘How is Gloria?’

‘Fine,’ I said.

Maybe I had not bothered to put enough conviction into that because he snorted and gave me a sharp look. ‘I’m a successful man,’ he said. ‘And the reason is that when a deal goes sour I pull out and take any losses. You don’t mind that bit of advice from an old man?’

I smiled. ‘The best thing about advice is that you don’t have to follow it.’

So I left him and went down to the thronged street in his private lift and joined the hurrying crowds eager to get home after the day’s work. I wasn’t particularly eager because I didn’t have a home; just a few walls and a roof. So I went to my club instead.

FOUR

I felt a shade better when I arrived at the office next morning. I had visited my fencing club after a long absence and two hours of heavy sabre work had relieved my frustrations and had also done something for the incipient thickening of the waist which comes from too much sitting behind a desk.

But the desk was still there so I sat behind it and looked for the information on Billson I had asked Joyce to look up. When I didn’t find it I called her in. ‘Didn’t you find anything on Billson?’

She blinked at me defensively. ‘It’s in your in-tray.’

I found it buried at the bottom—an envelope marked ‘Billson’—and grinned at her. ‘Nice try, Joyce; but I’ll work out my own priorities.’

When Brinton had injected funds into the firm it had grown with an almost explosive force and I had resolved to handle at least one case in the field every six months so as not to lose touch with the boys on the ground. Under the pressure of work that went the way of all good resolutions and I hadn’t been in the field for fifteen months. Maybe the Billson case was an opportunity to see if my cutting edge was still sharp.

I said abruptly, ‘I’ll be handing some of my work load to Mr Ellis.’

‘He’ll not like that,’ said Joyce.

‘He’d have to take the lot if I was knocked down by a car and broke a leg,’ I said. ‘It’ll do him good. Remind me to speak to him when he gets back from Manchester.’

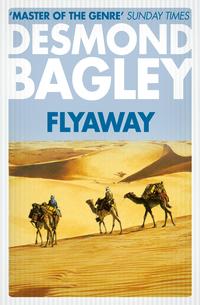

Joyce went away and I opened the envelope and took out a four-page article, a potted history of the life and times of Peter Billson, Aviation Pioneer—Sunday Supplement instant knowledge without pain. It was headed: The Strange Case of Flyaway Peter, and was illustrated with what were originally black-and-white photographs which had been tinted curious shades of blue and yellow to enliven the pages of what, after all, was supposed to be a colour magazine.

It boiled down to this. Billson, a Canadian, was born appropriately in 1903, the year the first aeroplane took to the sky. Too young to see service in the First World War, he was nourished on tales of the air fighting on the Western Front which excited his imagination and he became air mad. He was an engineering apprentice and, by the time he was 21, he had actually built his own plane. It wasn’t a good one—it crashed.

He was unlucky. The Golden Age of Aviation was under way and he was missing out on all the plums. Pioneer flying took money or a sponsor with money and he had neither. In the late 1920s Alan Cobham was flying to the Far East, Australia and South Africa; in 1927 Lindbergh flew the Atlantic solo, and then Byrd brought off the North and South Pole double. Came the early’ thirties and Amy Johnson, Jim Mollison, Amelia Earhart and Wiley Post were breaking records wholesale and Billson hadn’t had a look-in.

But he made it in the next phase. Breaking records was all very well, but now the route-proving stage had arrived which had to precede phase three—the regular commercial flight. Newspapers were cashing in on the public interest and organizing long-distance races such as the England-Australia Air Race of 1934, won by Scott and Campbell-Black. Billson came second in a race from Vancouver to Hawaii, and first in a mail-carrying test—Vancouver to Montreal. He was in there at last—a real heroic and intrepid birdman. It is hard to believe the adulation awarded those early fliers. Not even our modern astronauts are accorded the same attention.

It was about this time that some smart journalist gave him the nickname of Flyaway Peter, echoing the nursery rhyme. It was good publicity and Billson went along with the gag even to the extent of naming his newborn son Paul and, in 1936, when he entered the London to Cape Town Air Race he christened the Northrop ‘Gamma’ he flew Flyaway. It was one of the first of the all-metal aircraft.

The race was organized by a newspaper which beat the drum enthusiastically and announced that all entrants would be insured to the tune of £100,000 each in the case of a fatality. The race began. Billson put down in Algiers to refuel and then took off again, heading south. The plane was never seen again.

Billson’s wife, Helen, was naturally shocked and it was some weeks before she approached the newspaper about the insurance. The newspaper passed her on to the insurance company which dug in its heels and dithered. £100,000 was a lot of money in 1936. Finally it declared unequivocally that no payment would be forthcoming and Mrs Billson brought the case to court.

The courtroom was enlivened by a defence witness, a South African named Hendrik van Niekirk, who swore on oath that he had seen Billson, alive and well, in Durban four weeks after the race was over. It caused a sensation and no doubt the sales of the newspaper went up. The prosecution battered at van Niekirk but he stood up to it well. He had visited Canada and had met Billson there and he was in no doubt about his identification. Did he speak to Billson in Durban? No, he did not.

All very dicey.

The judge summed up and the case went to the jury which deliberated at length and then found for the insurance company. No £100,000 for Mrs Billson—who immediately appealed. The Appellate Court reversed the decision on a technicality—the trial judge had been a shade too precise in his instructions to the jury. The insurance company took it to the House of Lords who refused to have anything to do with it. Mrs Billson got her £100,000. Whether she lived happily ever after the writer of the article didn’t say.

So much for the subject matter—the tone was something else. Written by a skilled journalist, it was a very efficient hatchet job on the reputation of a man who could not answer back—dead or alive. It reeked of the envy of a small-minded man who got his kicks by pulling down men better than himself. If this was what Paul Billson had read then it wasn’t too surprising if he went off his trolley.

The article ended in a speculative vein. After pointing out that the insurance company had lost on a legal technicality, it went on:

The probability is very strong that Billson did survive the crash, if crash there was, and that Hendrik van Niekirk did see him in Durban. If this is so, and I think it is, then an enormous fraud was perpetrated. £100,000 is a lot of money anywhere and at any time. £100,000 in 1936 is equivalent to over £350,000 in our present-day debased currency.

If Peter Billson is still alive he will be 75 years old and will have lived a life of luxury. Rich men live long and the chances are that he is indeed still alive. Perhaps he will read these words. He might even conceive these words to be libellous. I am willing to risk it.

Flyaway Peter Billson, come back! Come back!

I was contemplating this bit of nastiness when Charlie Malleson came into the office. He said, ‘I’ve done a preliminary analysis of the consequences of losing the Whensley Group,’ and smiled sourly. ‘We’ll survive.’

‘Brinton,’ I said, and tilted my chair back. ‘He owns a quarter of our shares and accounts for a third of our business. We’ve got too many eggs in his basket. I’d like to know how much it would hurt if he cut loose from us completely.’ I paused, then added, ‘Or if we cut loose from him.’

Charlie looked alarmed. ‘Christ! it would be like having a leg cut off—without anaesthetic.’

‘It might happen.’

‘But why would you want to cut loose? The money he pumped in was the making of us.’

‘I know,’ I said. ‘But Brinton is a financial shark. Snapping up a profit is to him as mindless a reflex as when a real shark snaps up a tasty morsel. I think we’re vulnerable, Charlie.’

‘I don’t know why you’re getting so bloody hot under the collar all of a sudden,’ he said plaintively.

‘Don’t you?’ I leaned forward and the chair legs came down with a soft thud on to the thick pile carpet. ‘Last night, in a conversation lasting less than four minutes, we lost fifteen per cent of Brinton’s business. And why did we lose it? So that he can put the arm on Andrew McGovern who is apparently getting out of line. Or so Brinton says.’

‘Don’t you believe him?’

‘Whether he’s telling the truth or not isn’t the point. The point is that our business is being buggered in one of Brinton’s private schemes which has nothing to do with us.’

Charlie said slowly, ‘Yes, I see what you mean.’

I stared at him. ‘Do you, Charlie? I don’t think so. Take a good long look at what happened yesterday. We were manipulated by a minority shareholder who twisted us around his little finger.’

‘Oh, for God’s sake, Max! If McGovern doesn’t want us there’s not a damn thing we can do about it.’

‘I know that, but we could have done something which we didn’t. We could have held the Whensley Group to their contract which has just under a year to run. Instead, we all agreed at the AGM to pull out in ten days. We were manoeuvred into that, Charlie; Brinton had us dancing on strings.’

Charlie was silent.

I said, ‘And you know why we let it happen? We were too damned scared of losing Brinton’s money. We could have outvoted him singly or jointly, but we didn’t.’

‘No,’ said Charlie sharply. ‘Your vote would have downed him—you have 51 per cent. But I have only 24 to his 25.’

I sighed. ‘Okay, Charlie; my fault. But as I lay in bed last night I felt scared. I was scared of what I hadn’t done. And the thing that scared me most of all was the thought of the kind of man I was becoming. I didn’t start this business to jerk to any man’s string, and that’s why I say we have to cut loose from Brinton if possible. That’s why I want you to look for alternative sources of finance. We’re big enough to get it now.’

‘There may be something in what you say,’ said Charlie. ‘But I still think you’re blowing a gasket without due cause. You’re over-reacting, Max.’ He shrugged. ‘Still, I’ll look for outside money if only to keep you from blowing your top.’ He glanced at the magazine cutting on my desk. ‘What’s that?’

‘A story about Paul Billson’s father. You know—the accountant who vanished from Franklin Engineering.’

‘What’s the score on that one?’

I shook my head. ‘I don’t know. At first I had Paul Billson taped as being a little devalued in the intellect—running about eighty pence in the pound—but there are a couple of things which don’t add up.’

‘Well, you won’t have to worry about that now. Franklin is part of the Whensley Group.’

I looked up in surprise. ‘So it is.’ It had slipped my mind.

‘I’d hand over what you’ve got to Sir Andrew McGovern and wish him the best of British luck.’

I thought about that and shook my head. ‘No—Billson disappeared when we were in charge of security and there’s still a few days to the end of the month.’

‘Your sense of ethics is too strongly developed.’

‘I think I’ll follow up on this one myself,’ I said. ‘I started it so I might as well finish it. Jack Ellis can stand in for me. It’s time he was given more responsibility.’

Charlie nodded approvingly. ‘Do you think there’s anything in Billson’s disappearance—from the point of view of Franklin’s security, I mean?’