Floyd Around the Med

Table of Contents

Title Page

Introduction

Greece

Mezze, moussaka & myths

Chicken with lemons and raisins

Fricassée of spring Lamb

Mezze (Greek hors d'oeuvre)

Postcards from Greece

Sauté of spring lamb with apricots

Octopus

Ragout of octopus

Beef with green olives

Grilled fish with lemon sauce

Pasta rice with spinach

France

Toujours le garlic

Aubergine caviar

Fish soup

Provençal omelette cake

Postcards from France

Gratin of mussels

Sauté of new potatoes

Red mullet

Stuffed vegetables

Blanquette of vegetables

Turkey

Turkish delight?

Stuffed fish baked in filo pastry

Floyds turkish barbecue

Sauté of chicken

Minced beef and spinach

Spain

Lunch in the afternoon

Catalan broad bean salad

Red peppers stuffed wih salt cod purée

Partridges cooked in vinegar

Moorish Andalusian endive salad

Black pudding and sausages with almonds

Casserole of vegetables

Lobster in chocolate sauce

Grilled sardines

Tinto verano

Iced gazpacho

Paella

Fish baked in salt

Postcard from Spain

Muscle beach mango delice

Morocco & Tunisia

Of camels and couscous

Lamb couscous with vegetables

Brik

Sauté of beef

Mechouia

Preserved lemons

Lamb tagine with prunes

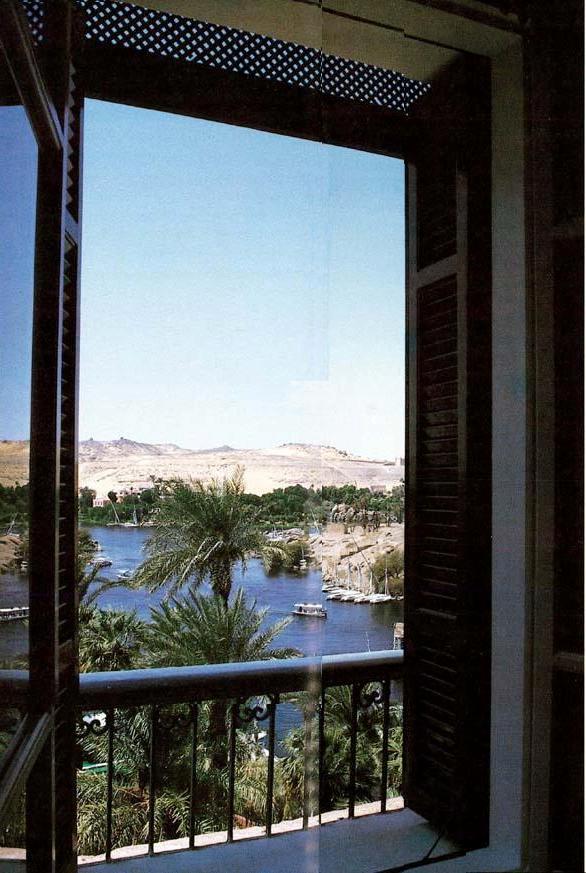

Egypt

Mummies, molokhia & monuments

Egyptian fish tagine

Braised okra

Rice with prawns and chickpeas

Egyptian green soup

Tahini sauce

Baked fish

Tabbouleu

Sauté of chicken

Egypt, a Postscript

Index

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

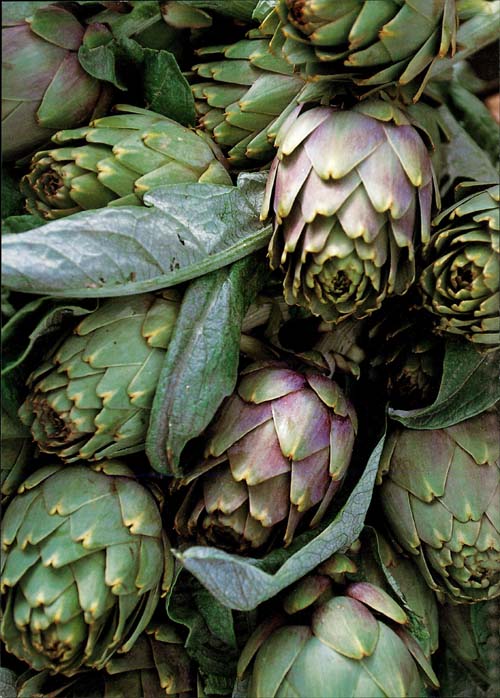

The primary flavours of the Mediterranean are olive oil, thyme, rosemary, basil, garlic and saffron. The main vegetables are aubergines, peppers, tomatoes and courgettes. All these are overlaid with a mist of lemon, nuts and spices from the East – nutmeg, cumin, cinnamon, cardamom, coriander, turmeric, chilli flakes, sea salt, black pepper, caraway and others. Rice, pasta, pulses and grains are preferred to the potato. Artichokes, spinach, celery leaves and mint are mixed with crunchy greens for salads.

But the Mediterranean, which laps the shores of Europe, Asia and Africa, is populated by Christians, Arabs and Jews, by Latins and Moors, some meat eaters, some vegetarians, some pork lovers, and some nut lovers. Some of the countries are highly developed and have refrigerators and microwaves; others have simple clay pots with a few glowing embers of charcoal. Irrespective of creed, culture and cash, everyone shares a common love of food, whether it be fish, goat, lamb, pigeons and all manner of fowl, or fruit.

The recipes in this book are authentic, although I have modified some. Many of them come from cooks who have never seen a television cookery show or read a cookery book. Indeed, many of them cannot read. They have never weighed or measured an ingredient in their lives, and may well time the cooking from the cockerel’s early-morning alarm call to the moment the shadow falls over the pigsty. As a consequence, these recipes require the reader to apply simple common sense to the quantities, the sizes of pots, the volume of liquid and the length of time things take to cook. Remember, this is not a workshop manual. Cooking is not a science. Cooking is a way of demonstrating your appreciation of nature and making a gift of kindness and love to those whose company you enjoy. And the love of good food, generosity and hospitality is central to the Mediterranean people’s way of life which, like olive oil, that indispensable liquid that flavours, cooks and heals, is as old as time and civilization, whether you are squatting on a rush mat in a hut on the banks of the River Nile or dining in the ornate splendour of Monte Carlo.

Note on the recipes

In most of the recipes in this book, quantities and timings are approximate. The style of cooking in the countries around the Mediterranean is completely different from that of northern Europe. People tend to live in extended families, and so they cook for eight to ten people. There is not a cook in the Mediterranean area who would give you a recipe for, let’s say, moussaka, or beef stifado, for four people. They simply make up a pot of the stuff, with enough ingredients to go round. Any left over would be reheated and served the next day.

It is important to note that the recipes in this book are not ‘dinner-party dishes’. Although they are all prepared with love and the freshest ingredients, they are a casual, everyday part of Mediterranean life. Family or guests invited to a birthday or a Sunday family reunion will not be expecting a formal four-course meal followed by coffee and mints. Right, having said all that, I will repeat myself, just to be on the safe side: common sense must be applied to the quantities, cooking times and serving of these dishes. Finally, every time a recipe requires olive oil, this means olive oil. There is no substitute for it if you wish the dish to taste authentic – except where I suggest peanut, sesame or walnut oil!

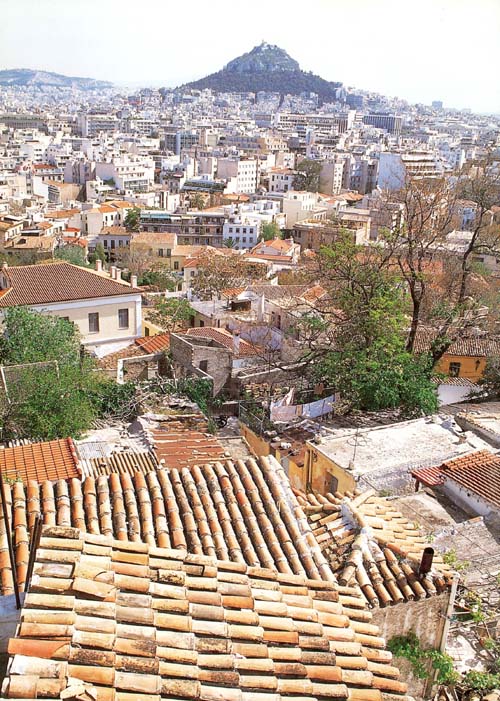

Greece

Mezze, moussaka & myths

There is much more to Greek cooking than moussaka, stuffed vine leaves, greasy kebabs stuffed into pitta bread pockets with chips, salad and mayonnaise, and the ubiquitous Greek salad with a slab of feta cheese sprinkled with dried oregano. This may be what most of us encounter on our Greek holidays but if you search around a bit you will discover some very fine dishes indeed. Take the aubergine, for example. It’s essential in a moussaka but there’s much more to it than that. You could write a whole book about cooking aubergines the Greek way. They can be made into a wonderfully refreshing salad, or stuffed with minced mutton or lamb and roasted in the oven, or deep-fried in batter, or fried in olive oil and served cold with a marinade of lemon juice, finely chopped garlic and parsley, coriander, fennel or dill. Courgettes can be given the same agreeable treatment as aubergines, and vegetables à la grecque (cooked in a lemon and olive oil marinade) are really most enjoyable. Baby vegetables such as leeks, onions and artichoke hearts can all be cooked in the same way as mushrooms à la grecque.

In Greece they love to cook with fresh herbs, such as coriander, dill, parsley, mint and spring onions, combined with lemon juice (I swear that Greek lemons produce some of the finest juice I have ever encountered). They like to use coriander seeds and cinnamon to flavour their dishes, and occasionally cumin. At its best, Greek cooking is light, refreshing, tasty and tangy – for example, lamb stewed with Cos lettuce or green peas, flavoured with a wonderful lemon sauce, is an exquisite dish. Stuffed vine leaves don’t have to be briny, vinegary things with congealed rice inside. Like cabbage leaves, they can be stuffed delightfully with a mixture of rice, fish or meat, maybe pine nuts, sultanas or currants.

chicken with lemons and raisins

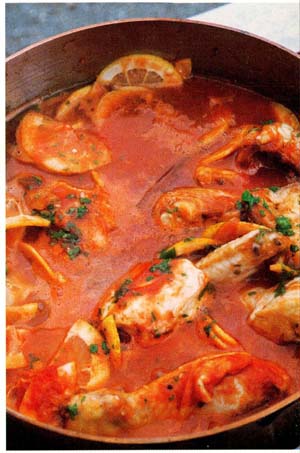

In this dish, which is really a simple chicken cooked in tomato sauce, we can see the influence that the Moors have had on Mediterranean cooking by the use of fruits and spices.

1 free range chicken (how heavy? I hear you cry! Well, I don’t know. If there are 2-4 of you, get a small one; more of you, get a great big one or two small ones! If the chicken has its liver and heart, so much the better) olive oil 2 onions, finely diced 4 fat cloves of garlic, very finely crushed about ½ bottle white wine about 500ml/18fl oz tomato sauce (buy this in a carton) 4 juicy lemons, cut in half, pips removed, then very, very, very finely sliced 1 cinnamon stick about 225g/8oz raisins, currants or sultanas 1 sprig of thyme 4-5 clovessea salt and black pepper

Joint the chicken, bones and all, into manageable morsels. In a large, shallow sauté pan or a deep frying pan, heat up some olive oil. The pan needs to be big enough to hold all the pieces of chicken in a single layer. Fry them on both sides until golden brown, then add the onions and garlic and brown them very lightly. At this stage, if you have the giblets from the chicken, add them and fry them too. Now pour in the wine so that it half covers the chicken and boil furiously until it has reduced, then add enough tomato sauce just to cover the chicken. Keep on cooking for a few minutes, then add the lemons, cinnamon, raisins, thyme and cloves. By now, since the chicken went into the pan, it will have been cooking for about 25 minutes. Stir the whole lot together and let it simmer gently until the chicken is tender and you have a fragrant, spicy, lemon-tanged tomato sauce.

I am not the kind of cook who offers (quote) serving suggestions (unquote!). It is up to you, but I think pasta, rice, vermicelli or salad would be good with this. Because, you see, this kind of dish, which is cooked with vegetables and fruit, just doesn’t need a plate of carrots, green beans or similar, next to it. A few chips and olive oil might be quite nice, however!

A NOTE ON HERBS

As a general rule, branches of dried herbs such as thyme and rosemary work best when barbecuing and grilling because they are cooked into the overall flavour; they are also very good in casseroles and stews that require long cooking. However, when the herb is used as an edible garnish (i.e. not cooked) or only cooked very lightly, fresh herbs are essential.

fricassée of spring lamb with green peas and egg and lemon sauce

Egg and lemon sauce, known as avgolemono, is served with vegetables, meat, chicken and fish throughout Greece. Since this is a spring dish it is essential that the lamb is young and fresh, not frozen. Throughout the Mediterranean, this fricassée would be prepared with milk-fed lamb at best and, at worst, meat from a very, very young sheep.

SERVES 6 about 1.5-2kg/3¼-4½lb leg of spring lamb (you might have to buy 1½ legs) 175g/6oz unsalted butter 500g/1lb 2oz baby leeks (the thickness of your average fountain pen), the white and green parts cut into 4cm/1½ inch batons ½ hearty, dark-green Cos (romaine) lettuce, ripped into rough pieces 1.5kg/3¼lb small frozen peas (yes, frozen, because unless you have access to the tenderest of fresh garden peas, this dish will be ruined by those tough old things the size of golf balls, so-called fresh garden peas from the average greengrocer; also, frozen peas contain their own moisture) 1 bunch of fresh dill or coriander, or parsley or even chives, chopped sea salt and black pepper FOR THE SAUCE: 1 heaped tbsp butter 1 tbsp plain flour juice of 5 or 6 lemons (possibly less if you are making this on holiday where lemons grow; possibly more if you are using the slightly less juicy ones at home) 2 eggs and 4 egg yolksCut the lamb off the bone into nice bite-sized pieces. Melt half the butter in a cast-iron, copper or other heavy-based wide casserole and fry the lamb pieces until they are browned on all sides. Because it is spring lamb it will not take very long to cook, so just brown it lightly. Then stir in the leeks and cook for a few minutes to soften them a little. Throw in the roughly torn up lettuce, then the frozen (yes, still frozen) peas and fresh herbs. Add one or two cups of water and the remaining butter, then season with salt and pepper. Stir the whole lot round so everything is combined, put the lid on and simmer gently for about 30-45 minutes. Inspect and taste the dish from time to time to make sure that the peas are defrosting, the lamb is cooking and all the juices are amalgamating.

When you think the lamb is almost cooked, strain off about a cupful of the cooking liquid, leaving only a small amount in the pan. Now, in a separate heavy-based pan, make the sauce. Melt the butter, add the flour and whisk well, so that you have a golden, but not burnt, roux. Whisk in the cooking liquid you have taken from the lamb and peas until you have a thick, smooth sauce. Now, over a low heat whisk in some lemon juice until it has almost the consistency of custard. In a jug, lightly whisk together the eggs and egg yolks. With the heat switched off, gradually add the beaten eggs to the sauce, whisking furiously, until you have what does, in fact, look like custard. If the pan is too hot or you whisk too slowly, you will curdle the whole thing, so do be careful.

Put the lamb and peas on to a serving platter and pour over the egg and lemon sauce.

mezze (Greek hors d’oeuvre)

In the South of France salads of dandelion leaves are common but in Greece dandelions are more likely to be stir-fried with wonderful olive oil, lemon juice, cinnamon and salt and pepper. The bitterness of the leaves is mellowed by the sweetness of the oil and spiked with the cinnamon and lemon juice.

It is quite hard to find these dishes properly cooked. Although the Greeks have all these wonderful recipes there don’t appear to be many people interested in producing them. The basic taverna idea is a good one: a dozen or so stews, soups or ragouts, plus a selection of vegetable dishes, are cooked in the morning and kept warm all day in a bain marie. This means quick eating, plus you can see what you’re getting, but by the evening the dishes tend to be a little stale and overcooked. A good tip is to eat in tavernas at lunchtime but in the evenings go to places that cook to order on the barbecue. In this way you can enjoy barbecued octopus or a variety of fresh fish or shellfish or excellent – sometimes – lamb souvlakia (kebabs), or offal kebabs, or freshly cooked minced meat balls and delicate, tiny lamb chops simply grilled and eaten with a squeeze of lemon juice.

Of course, one of the great joys of eating in Greece is when you come across a restaurant or bar that takes trouble over its mezze. These are the Greek hors d’oeuvre, or the Greek tapas if you wish. The ancient Greeks claimed to have invented mezze, although visitors to Athens thought it was just an excuse for the Athenians’ miserliness. The ancient Greek writer Lyceus reckoned an Athenian dinner was an insult. He felt affronted to be offered five or six small plates, one with garlic, another with some sea urchins or a little piece of marinated fish or a few cockles, possibly a few olives. But it was the beginning. Today, of course, mezze can be truly pleasing. At its simplest it might be a bowl of pickled vegetables such as carrots, chillies or cauliflower and a dish of nutty, delicious olives, or it might be a mini feast of vegetables à la grecque or little filo pastry pockets filled with cream cheese and spinach, or tzatziki – a wonderfully refreshing yoghurt dip – or stuffed vine leaves, or the oddly named aubergine salad, which is in fact a beautiful purée of baked aubergines, or taramosalata which, sadly, throughout Greece is pretty insipid, artificially coloured goo. You’ll find my recipe much better than anything you will eat in Greece – ha! Or raw fish marinated with lemon juice and olive oil, or just little pieces of marinated grilled octopus. Much of Greek cooking is done by rule of thumb and experience rather than by careful measuring. Greeks (like most Mediterranean people) don’t cook dinner parties for two, or four, or six, like people in northern Europe do. They cook as much as the dish will hold for as many people as they think can eat it. So you must, I warn you, when you attempt any of these recipes bear in mind that all measurements, times and weights are approximate. Please use common sense.

Olives are indispensable to the Mediterranean table.

mushrooms à la grecque

750g/1lb 10oz very small mushrooms (the size of an average olive) juice of 4 lemons olive oil 1 large onion, very finely diced 750g/1lb 10oz tomatoes, skinned, deseeded and finely diced 1 level tbsp of equal quantities of crushed peppercorns and coriander seeds 2 or 3 bay leaves 1 sprig of thyme 1 tbsp tomato purée 1 bunch of fresh coriander, chopped 1 sea saltFirst, clean the mushrooms if necessary – if you decide to wash them, make sure you dry them very carefully – then marinate them in the lemon juice for 10-15 minutes.

Secondly, heat some olive oil in a shallow sauté pan or a large, deep frying pan, add the onion and tomatoes and fry swiftly for a minute or two. Then add the peppercorns and coriander seeds, bay leaves, thyme, tomato puree and possibly a dash of water. Bring to the boil and simmer for a few minutes until you have a nice tangy sauce. Now add the mushrooms and lemon juice and cook for 5-6 minutes more or until the mushrooms are cooked and the sauce has reduced a little. Add salt to taste. Tip into a serving dish. When cool, chill in the refrigerator. Serve with chopped coriander leaves sprinkled over.