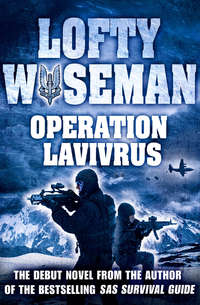

Operation Lavivrus

JOHN ‘LOFTY’ WISEMAN

OPERATION LAVIVRUS

Copyright

Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in 2012

Text © John Wiseman, 2012

John Wiseman asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 2012.

Cover photographs © Nik Keevil (soldiers); Magdalena Biskup Travel Photography/Getty Images (mountains); Shutterstock (plane).

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2012 ISBN: 9780007463275

Version: 2017-08-09

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Keep Reading

About the Author

About the Publisher

Prologue

Although the air temperature was just above freezing, the combined effect of the rain and wind generated a wind-chill factor of –20°, yet the blackened face of the soldier was beaded with sweat, blending with the rain to form a salty fluid that stung his eyes. It ran down his face into his mouth, mixing with the camouflage cream he wore, leaving a foul taste in his dry, acidulous throat.

Fear of compromise kept the adrenalin pumping, forcing tired eyes to focus. He tried to keep the blinking to a minimum, regardless of the stinging onslaught. He longed to close his eyes and find refuge in a dry, warm place, far away from here, but that had to wait.

He reached up, and a cold rivulet of water ran down his spine, causing a shiver to start in his tightly clenched buttocks, running down each leg and making his whole body shake. The noise of the magnet as it attached the innocent-looking cylinder to the target was barely audible, masked by the shrieking wind, but to the operative who was carefully placing the device the noise sounded like a railway truck coupling with a goods train.

His heart was hammering, threatening to burst through the windproof material of his camouflaged smock. Blood pulsed at his temples, and the throbbing in his ears was amplified by the howling wind, making him dizzy and causing a slight tremble in his cautious fingers.

‘Get a grip, man. Concentrate,’ he reminded himself. After shaking and pulling on the device, satisfying himself that it was firmly fixed, he dropped down onto one knee, appraising his surroundings.

Common sense told him to run, but instinct commanded him to stay. Every fibre and sinew in his body protested at this lull in activity, screaming to be stretched, to generate heat, to carry him away from the lethal profile that towered above him.

He opened his mouth slightly, which helped improve his hearing and reduced the pulse resonating in his skull. His blood was surging through every vessel in his body, like floodwater in a storm drain. It takes a special type of man to be able to handle such pressure. Training helps to condition the body, but it is experience that conditions the mind.

By concentrating on his breathing he managed to keep everything under control. He blocked out the discomfort of being cold and wet, controlling all the emotions that urged him to run. Inhaling strongly through his nose to a five count, holding each breath for the same duration before exhaling forcibly through the mouth to a count of five, enabled him to keep his senses sharp and helped retain coordination.

He moved deeper into the shadows, seeking shelter from the driving rain. The surrounding mass of unyielding concrete gave him some respite, but only increased the destructive intensity of the wind.

Although the weather was foul it suited what he was doing; he couldn’t have hoped to achieve his aim in anything less. Wind is a killer; it was unrelenting, fiercely probing the thick concrete walls. Searching for weaknesses, it veered continuously, trying new angles of attack. In contrast to the concrete mass, the sinister grey-blue shape offered little resistance to the wind, allowing it to whistle around its streamlined profile, frustrating the gale, forcing it to take vengeance on more vulnerable targets. Whistling and whining in annoyance, it attacked the soldier. Just when he thought it couldn’t get any stronger, a gust would threaten to bowl him over. Only by using all his senses and instincts could he succeed. They had served him well in the past. His hearing battled against the elements, trying to detect any sounds that might compromise him, but this sense was neutralised, so he depended on others. He could smell the heavy odours of paraffin and hydraulic fluid, and he sniffed the air regularly. Cigarette smoke, unwashed bodies and animal smells would all carry on the wind.

His eyes never stopped moving, searching the area for any sign of movement. As he crouched low everything was in silhouette, giving him early warning of movement. He avoided looking directly at the sodium lights that illuminated the perimeter, protecting his night vision, using his peripheral vision to scan the shadows. He felt very exposed as the area was too light. Every puddle in the wet tarmac mirrored the light, making him feel as though he was under scrutiny. Only the shadows and the weather were in his favour.

The sweat was drying now, causing him to shiver. Every time he moved, however slightly, a warm part of his body was invaded by a fresh attack of cold water, chilling his frame.

Resisting the temptation to pull down his woollen cap or use the hood of his smock to cover his freezing ears took great willpower. Although his hearing was ineffective, he needed the discomfort of his exposed ears to keep him alert. Forty per cent of body heat is lost through the head, so he was glad he had spent the time looking for his lucky balaclava. It seemed years ago that he was frantically turning out his locker searching for the elusive item. As he readjusted it, his old sergeant major’s advice from training came to mind: ‘If your feet are cold, put your hat on.’ It was dangerous to reminisce, however, and a sure sign of fatigue. To combat this he removed the hat and wrung it out violently, before swiftly replacing it. This brief action cleared his head, allowing him to refocus on his surroundings.

Cradling the AR15 tightly across his chest, instinctively covering the working parts, he prepared to move. Taking a deep breath he steeled his body in anticipation of a fresh assault of cold water. He checked all his pockets and the fastenings on all the pouches that hung off his belt. Every movement was an effort, as his hands were numb and his limbs stiff. He rubbed his knee, trying to restore circulation, pre-empting the pain that was sure to follow.

From under his green and black patterned smock he pulled out his watch, which was suspended around his neck with a length of para cord. ‘So far so good,’ he thought, nervously fingering the two syrettes of morphine that were taped either side of the watch. ‘I hope I won’t need these,’ he mused, stowing the necklace back inside his clothing.

He straightened up slowly, overcoming the pain of protesting joints, and moved to the front of the bay. He crouched low with his weapon ready, flicking the safety catch on and off. He stayed in the shadows beside a piece of machinery, knowing that soon he would have to cross the curtain of light that illuminated the fence. For the first time he realised he was hungry. Food might ease the gnawing sensation in his stomach.

Trying to remember when he last slept or had a proper meal was too much for his mind to process; only the dangers at hand seemed relevant. He couldn’t afford to dwell on creature comforts.

Inactivity had caused his feet to go numb, so he took it in turns to put all his weight on one foot while he wriggled the toes on the other. He did the same with his hands, changing over the weapon regularly from one hand to the other. His knees were burning and a small nagging pain in his back reminded him of the free-fall descent he had made recently. It all seemed so long ago, like part of a sketchy dream he barely remembered.

As he scanned the area his eyes kept returning to the same object, slightly behind him and suspended six feet from the ground. It was long, white and menacing. It had four small fins sprouting a few feet behind a needle-sharp nose, with four larger triangular ones towards the rear. He was close enough to be able to make out the bold black lettering stencilled on its side. The word ‘AEROSPATIALE’ revived distant memories.

Sometimes the eyes can play tricks on you, especially after they have been battered continuously by rain and wind, and the soldier thought he might have imagined seeing a shadow that wasn’t there a minute ago. It caused a tightening in his throat and a strange flutter in his heart. He studied the area, and sure enough the shadow got bigger. ‘Here we go again,’ he thought, easing off the safety catch and bringing the butt of the rifle up to his shoulder.

CHAPTER ONE

For a man who had had less than two hours sleep, Tony looked remarkably alert. Settled well down in the driver’s seat but with his head erect, he overtook the slower motorway traffic with no apparent effort. His driving was smooth, anticipating what the other road users were doing. He looked as far forward as possible, dealing with things before they happened so they wouldn’t impede his progress. He checked his mirrors regularly, knowing exactly what was behind him. Although he was relaxed, he played little games that helped pass the time. He looked at car number plates and from the letters made up abbreviations.

He found driving gave him time to think and consider his life. The long line of lorries in the inside lane brought back childhood memories. As a kid he had wanted to be a lorry driver. His uncle would pick him up in the school holidays and take him on trips in a timber truck. It was an ex-army vehicle, and Tony thought his uncle had the best job in the world. He looked at all the trucks he was now passing, however, and didn’t envy the drivers at all. His dream of being a lorry driver was soon replaced by the urge to become a racing driver. At the house where he was born in South-East London, his mother had an upright mangle; for hours he would sit at one end and pretended the large cast-iron wheel was a steering wheel, controlling a Ferrari or Maserati.

The weak April sunshine favoured driving: visibility was good and the traffic light. Contrary to the weather forecast it was dry at present, but clouds were building up and the dark sky ahead looked ominous.

Tony was dreading having to use the wipers because he knew the washer bottle was empty. Due to the early morning start he was pushed for time. The lifeless form beside him was partly to blame for this. All the dirt on the screen would just get smeared if the rain was light, and he hated driving if his vision was impaired.

Although the sun was welcome it could be a nuisance. It was in his eyes when he was heading east to London in the morning, and again as he returned west towards Hereford in the afternoon. He had lost his sunglasses and refused to buy a new pair. ‘They’re for posers,’ he thought, tenderly rubbing his ear.

He started whistling ‘April Showers’, keeping it quiet to avoid disturbing his companion. He gave up after a few bars as his swollen lips couldn’t form the notes properly. He took a swig from the water bottle he had beside him, trying to lubricate a mouth that tasted like the bottom of a baby’s pram.

A lot had happened in the past three weeks, and Tony started reflecting on recent events. Three weeks ago the entire regiment was assembled in the Blue Room. This was a converted gun shed and the only place big enough to accommodate everyone. It echoed with the sound of many voices trying to work out what this gathering was all about. The din ceased abruptly with the appearance of a tall, authoritative figure who stared fiercely at his audience. When he was finally satisfied that he had everyone’s attention, he began speaking.

‘Gentlemen, at 0830 hours this morning a large force of Argentinian marines invaded the Falkland Islands.’ The Colonel went on to explain how this affected the nation and what they were going to do about it. Most people in his audience didn’t have a clue where the Falklands were. Some thought they were off the coast of Scotland.

Since this briefing A and D Squadrons had been despatched southwards to assess the situation. Tony had watched their departure with envy and was wondering when his turn would come. Rumours spread faster than dysentery at times like these.

A loud rumbling noise caused by running over cat’s-eyes brought Tony back to the present. The repeating vibrations transmitted up the steering column went through his shoulders to his neck, causing his head to shake and reminding him of the fragile condition of his head.

After a heavy night in the club he was wishing he had taken the soft option and had an early night. He was grateful that the three-hour journey was mainly on motorways and his partner could drive the return leg.

At present, however, the guy slumped in the seat next to him wasn’t any use to man or beast. His breathing was slow and deep, broken only occasionally by a loud snatch for air. This happened every time he forgot to breathe, which became more frequent the longer he slept. Contorted as he was, tangled up in the seat belt in a foetal position, it was a wonder he could breathe at all. A road atlas lay open on the floor with its pages crumpled under a pair of well-worn chukka boots, carelessly discarded. These emitted a strong smell of mature feet, intensified by the efficient heater. But the smell, instead of offending Tony, gave him a sense of security, knowing he had a comrade close by. As much as he would like to relax like his passenger, he opened the window to let in fresh air.

Yesterday afternoon he had played rugby, and he was now feeling the after-effects. His ears were so tender that he could hardly bear to touch them. This was the main reason why he didn’t open the window more often – the inrush of air was too much. They still bore traces of Vaseline because of their tenderness, and they had gone untouched in the shower. A fly had mysteriously appeared, and buzzed around the interior of the car; Tony thought, If it lands on my ear, it’s war. The tenderness of his ears was another reason Tony didn’t wear sunglasses. One ear was split along the entire length of the outer fold, and the other was ripped where it joined his head, distorted by trapped blood so it looked like a piece of pastry thrown on at random by a drunken chef.

He favoured his neck, carrying his head in a fixed position with his strong chin tucked in. When he wanted to look sideways he pivoted the whole of his upper body, trying to avoid any stress on his neck. His eyes pivoted in their sockets as he constantly checked the mirrors – offside, nearside, interior. From time to time he also checked on his lifeless companion, wondering with consuming jealousy how he could sleep so innocently. Every now and again he would try rotating his head, keeping the chin tight to the chest, but the pain and the gristly grating forced him to stop.

The snoring went on uninterrupted, regardless of Tony’s frequent glares, and although he had played in the same team his friend didn’t have a scratch on him. This rankled Tony because he was a forward who fought for every ball, taking the knocks so he could pass the ball to the backs. His work at the coalface went unnoticed, but the backs were in the spotlight, sprinting up the touchline with the encouragement of the crowd. Tony’s companion was the product of a public school where rugby was more of a religion than a sport. His handling and speed would get him a start in most teams: he was a fine player, and yesterday he had scored two tries seemingly with almost no effort. He was always in the right place at the right time, another sign of a good player. Tony’s first love was football, and he didn’t play rugby till he was in the army. ‘Typical!’ Tony thought. ‘Here I am, battered and driving, while fancy pants is sleeping like a baby.’

Apart from the discomfort he was happy. The build-up training was going well, and the rugby match, although intense, was light relief from all the night exercises, tactics and skills training that his squadron was engaged in. Inter-squadron games were normally banned because of the high casualty rate. Victory made the pain more bearable, and he smiled to himself as he remembered the looks on the other team’s faces when the final whistle blew. The slumped figure next to Tony had played a big part in the win; they started as underdogs, but surprised everyone by lifting the Inter-Squadrons Rugby Shield.

Traffic was building up as they skirted the capital, and Tony noticed how aggressive the drivers were compared with Hereford. Everyone changed lanes, often without any warning, and glared when the same was done to them. Tony just smiled and mixed it with the best of them.

‘This should be an interesting visit,’ he thought, looking forward to meeting the boffins at the research establishment where they would arrive shortly.

Tony Watkins was thirty-four and had been in the army for sixteen years. He joined the Paras initially, and couldn’t stay out of trouble. When he signed on at Blackheath he had never heard of the SAS, as few people had.

As soon as he started his basic training with the Paras in Aldershot, Tony realised he had made a big mistake. The Paras were definitely not for him. His sense of humour and loathing of discipline didn’t go down well with the staff of Maida Barracks. Things didn’t get any better when he was posted to a battalion; in fact they got worse. He was super-fit, a natural athlete, and enjoyed all the physical stuff, but all the bull was like shackles around his body. Cleaning, sweeping and polishing were not for him. He had to get out.

Salvation came in the form of a soldier who was in transit from the SAS, just returning to Malaya after inter-tour leave. Tony got talking to him and was introduced to the Regiment. He soon became mesmerised by their exploits in the jungles of Malaya. Tracking down the bad guys, living in swamps and parachuting into trees – that was more to his liking than cleaning dixies and picking up leaves.

Selection for the Regiment was tough, but Tony loved every minute of it. Six months flew by. He had finally found a use for his endless energy and was soon recognised as an outstanding soldier. It was an individual effort, and he soon learnt self-discipline. This helped him to control a quick temper and think before reacting. As a kid he was too keen to lash out at anyone who upset him.

After his tough upbringing in South London he found the life easy. He tackled all the training with a passion, excelling at everything. Promotion came fast, and he was already the troop staff sergeant of 2 Troop A Squadron. The intense regime of regimental life was natural for him; he wouldn’t change it for anything. 2 Troop was the free-fall troop, and they prided themselves on being the best and fittest troop in the Regiment.

Signalling early, Tony pulled into the nearside lane and turned off the motorway. The silky-smooth V8 engine of the Range Rover pulled strongly as they climbed a steep road cut in the side of a chalky hill. The scarred white landscape was evidence of a road expansion scheme, and the volume of traffic justified this. It was all heading to London, two lanes bumper to bumper, with most cars having only a solitary driver in, usually with a face longer than a gas-man’s cape.

Near the top of the hill was a slip road that led to the main entrance of Fort Bamstead. Tony slotted in between the slow-moving trucks and turned off.

The establishment nestled around the hill, sprawling down a deep gulley. It was screened by trees and shrubs, with no signs to advertise its location. The locals had long forgotten its presence, and were not aware that some of the best brains in the country worked here. Rows of majestic oaks lined the lane on both sides, and the unusually large silent policeman caught Tony out. He was looking for hidden cameras and hit it going too fast, causing the vehicle to shudder. He took more care when he reached the next ramp, but at least he got a reaction from the living dead lying beside him.

Stirring for the first time, the crumpled figure alongside Tony started to sit up. He opened sticky eyes, running his tongue over dry lips. His mouth opened wide in a yawn that Tony had to copy. He stretched slowly, unwinding to his full length with arms extended above his head, playfully pushing Tony on the shoulder. ‘Here already, Tony? That was quick.’ He yawned again and ground his teeth, using his tongue to search his mouth for moisture.

Tony stopped in front of a pair of heavy iron gates, waiting for someone to come out of the guardroom on the right. His companion was still yawning and sorting out his footwear. It took ages before a uniformed figure appeared, clipboard in one hand and pen poised in the other. The policeman marched smartly towards them, bracing himself against the freshening wind. He looked through the gate, comparing the vehicle’s registration number with the memo on his clipboard, before finally saying, ‘Park your vehicle over there,’ indicating a large lay-by, ‘and bring your ID to the window over there,’ nodding towards the building. He noted down the time, skilfully using the wind to keep the pages flat.

‘You’re not looking your best this morning, Tony,’ his passenger commented.

Tony had to bite hard on his tongue. He had been driving for three hours while Peter, his passenger, slept. ‘It’s all your fault, Pete. I was ready to turn in at midnight, but you had to order another bottle.’

Ignoring the arguing couple, the policeman fumbled with a large bunch of keys to open a small side gate before scurrying back to his warm refuge like Dracula at sunrise.

Ministry of Defence policemen all come out of the same mould. They are usually ex-servicemen with an exaggerated military bearing, sporting a regulation short back and sides, with a small, neat moustache. If they have a failing it is for being too officious, and a reluctance to be parted from their kettle and electric fire.

Tony said, ‘You stay and rest, Pete, while I go and sign us in.’ As he walked towards the window it was second nature to examine his surroundings. He noted the closed-circuit cameras and the powerful spotlights. The close-linked security fence with razor wire on top brought back some painful memories. On many occasions he had spent time climbing and cutting it, trying to avoid its painful spikes.