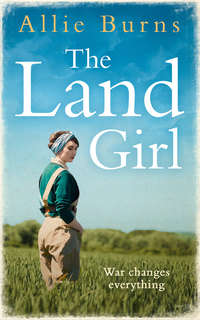

The Land Girl: An unforgettable historical novel of love and hope

She didn’t say another word to Emily; she didn’t even notice her, for the rest of the day.

Emily imagined conversations with Theo. She didn’t have his address in Yorkshire, so she pictured him rapt when she whispered to his photograph the tale of Mrs Tipton’s chickens following her all the way home or when Lily had escaped from the paddock and left a pat on their lawn.

*

August 1915

She’d thought of little else, since she’d decided that she would meet with Theo on his return to the Front and arranged to visit Grandmother in London to coincide with the end of his leave.

‘I’ve asked Norah Peters to come and sit with you. Grandmother says it’s urgent,’ she lied. She would have to pray that Grandmother didn’t call or write to Mother and tell her that the visit had been Emily’s idea.

She allowed an hour between her arrival in London and when she would be at Grandmother’s to meet with Theo on his way back to the Front. She should perhaps have brought a chaperone; it was clear that he was a passionate man, but she reasoned they were meeting in daylight, and she’d make sure he understood that just because she was deceiving her Mother, it didn’t mean she was fast.

She sat on the edge of her seat at the tea rooms, bolt upright. She would raise a hand this time if he tried to kiss her, but despite her anxiety she couldn’t keep the smile from her face. She toyed with a stray lock of hair, twirling it around her finger, and laughing at just about everything Theo said, even when it wasn’t that funny. She couldn’t control it.

He didn’t say anything about the proposal this time. His eyes were soft and warm; his gaze wasn’t probing. She had rejected him, but it was for the best, and the time at home would have given him the chance to think it through and see that it was madness. It had been romantic, and why shouldn’t he want to go back to war with a sweetheart waiting for him at home?

Since she’d been at the women’s march, she was resolved to do some war work, and just as soon as Mother was stronger she would tackle the subject again, but this time she would have the backing of John and Mr Tipton.

‘Grab the opportunity, girl,’ he said.

When the hour was up, he walked her to the corner of her Grandmother’s mews. He kept a respectable distance this time.

‘Don’t look so worried,’ he said. ‘I’m on my best behaviour today. I won’t be getting carried away. I got a bit overexcited last time, didn’t I? The company of a beautiful, clever girl, well, I was flattered. Can you blame me?’ She held out her palm and waved away his concerns. ‘But I haven’t given up on the idea of marrying you. I admire your spirit,’ he said. ‘I think it’s just the tonic I need.’

He cupped her elbow with his palm, and said, ‘May I?’

She nodded, and he pecked her on the cheek, one warm kiss, his breath caressing her skin.

‘Don’t forget to write,’ he said.

She waved, holding her other palm to her cheek.

When she returned in the evening she trod the hallway floorboards quietly, gauging the atmosphere in the house as to whether Grandmother had telephoned to tell Mother that Emily had arrived for her visit flushed and late. Grandmother had made her views on Emily travelling about London alone very clear, but with more and more young women working now, and so many men away, they couldn’t possibly be expected to be accompanied everywhere. The older ones would always cling on to the old way of doing things. It was a sign their ideas were close to being replaced.

The sitting room was empty. The muted fire was dying down without anyone there to tend it. All was quiet and still. She was about to quit while ahead and go straight to bed, when her mother came to life in the chair that faced out towards the window.

Even in the dim light, Mother was paler than usual. Despite the fire she looked frozen. Then Mother blinked, but that was the only movement. ‘Where were you?’ she asked, her voice thin and choked.

‘Some silly cows found their way onto the line near Sidcup,’ Emily said. She clenched her fists and waited. She was about to excuse herself, but something stopped her from speaking. Resting on her mother’s lap, loosely in her grasp, was a yellow slip of paper.

‘What’s that?’ Emily said.

Her legs were jittery, too weak to move her. Her mother didn’t speak. She had to cross that vast space of floorboards to reach her. One. Two. Three. Four. Her boots clipped on the floorboards. Unable to catch her own breath. She slid the piece of paper out of Mother’s flimsy grasp.

Her eyes scanned the typed words …

regret to inform …

… report has been received from the War Office …

… Name: Cotham J …

Her hands shook. The East Kent buffs had been under siege at the Battle of the Hooge near Ypres. Her brother was missing in action. She concentrated on the typed words: was posted as ‘missing’ on the … 30th July 1915.

‘He’s only been back there a week,’ she said. ‘It says that missing doesn’t necessarily mean …’ She couldn’t say the last word. She had read about that battle in the newspaper; it was the first time the enemy had used a flamethrower. She read on. ‘It says that he may be a prisoner of war, or have become temporarily separated from his regiment.’

The village doctor had received a telegram like this about his eldest son. The son had turned up several months later, in a German prisoner of war camp.

‘Yes, all is not lost,’ Mother said. A lightning strike of a smile, pained and twisted, flashed onto her face.

‘They say if he’s been captured that unofficial news is likely to reach us first, and we should notify them at once.’

Emily paused for a moment, tried to imagine John in a prisoner of war camp, or in a front-line hospital unaccounted for; perhaps a nasty blow to the head had caused him to forget who he was.

The letter seemed to be encouraging them to think he’d been captured, and they surely wouldn’t give them hope without good reason.

But still, however would they cope with the wait? Mother’s knitting needles and wool were discarded by her feet, her lips tinged blue. Hands trembling, pupils dilated, she wheezed.

‘Mother, can you breathe?’ Emily asked, her own throat constricting so much she could hardly catch her own breath. After a few moments Mother inhaled, panted, and slumped forwards.

‘It’s been a terrible shock,’ Mother said. ‘The letter came in the first post.’

‘You’re shivering,’ Emily said. She stepped out to speak to Daisy, suggested they call out the doctor and give her a sedative.

‘I need to lie down,’ Mother said when Emily returned.

Emily perched on the end of Mother’s dark oak bed. Mother was tucked up and they prayed quietly together for John’s return, and silently she wished for Theo’s safety too, for good measure. Mother’s face glistened with the residue of grease that her cold cream had left behind. Her hands flat on the bedspread, she stared off towards the window and didn’t say a word. Mother had managed her regular night-time rituals – that had to be a sign that everything would be all right, didn’t it?

‘Oh, John,’ Emily whispered to herself later in her own room.

The British army had lost her dear, sweet brother. How could she sleep until they found him and returned him safely home?

Chapter Eight

August 1915

Dearest Emily,

What terribly distressing news. My thoughts and prayers are with you and your family, and of course John. We mustn’t lose hope that he’ll be found and returned to you safe and sound.

Fondest wishes

Theo

The darkness pressed up against each of the window’s panes, but she was too alert to think of going back to sleep. She pulled the heavy burgundy damask curtains along their runners anyway, ready for the day that wasn’t yet prepared for her.

If she lay down again her mind would whirl and make John’s smile merge with Theo’s, their voices becoming one, until she couldn’t remember whose was whose. Who had said what, who had comforted her, and who had advised her. The tiredness had muddled her mind until she could no longer distinguish one from the other.

She couldn’t stay inside and whilst roaming about she found Mr Tipton in the shippon supervising the milking. She told him about John missing in action and without hesitation he embraced her, warm and clammy, his short arms stretching around her shoulders.

‘I need to keep busy. I can’t sit around up at the house. Can you give me something to do?’

She would worry about Mother later. She had insisted that Emily stayed at the house with her, but she was drugged and drowsy and Emily doubted she’d notice if she was gone.

Out of the corner of her eye, she caught a glimpse of Mr Tipton wiping away the tears with the back of his sleeve.

John was somehow missing like a hoe or a scythe, not a living, breathing person. He had said it could happen and she’d pushed the thought of it aside. He’d asked her to take care of Mother, but their problems were bigger than her – what about the house, the estate, the farm? Would they have to sell up if John didn’t come home? If only she’d asked him what it was that he meant, what she would need to accept and how she might be of best help to Mother.

Mid-morning, as she was going into the farmhouse for a cup of tea, she did a double take as Mother, holding her skirts aloft to reveal her heeled boots, stepped around the puddles and shooed away Mrs Tipton’s welcoming committee of chickens.

‘Emily dear, there you are.’

Mother had aged twenty years in that one night. Puffy pillows had gathered beneath her eyes, new hoods hung over them and shadows lurked beneath her cheekbones.

‘Has there been more news?’ Emily asked, realising that this was how it would be now: waiting and wondering when news of John would come.

‘I’m just so astonished that you deserted me,’ Mother continued. ‘I think you should come back to the house.’

‘Will Cecil come home?’ she asked hopefully.

‘I’ve sent him a telegram,’ Mother said. ‘I insisted he stay in Oxford. His studies mustn’t be interrupted. We must carry on as usual.’

She suggested Mother pay a visit to Hawk; the stallion had grown restless in his stables at Mother’s voice. His hooves dragged across the cobbles. It had been so long since Mother had ridden him and yet the faithful old beast was still loyal. He might be the balm, the connection that Mother needed.

‘I want to see John, not a horse.’

Emily raised a boot to a too-brave hen. She could never say the right thing.

*

She and Mother spent the afternoon in the conservatory, amongst the potted palms and ferns, Mother with a pristine newspaper folded in half across her blanketed knee. She faced the vegetable garden that Emily had dug with John when he’d been home on leave.

‘It makes me sad; my rose garden all ploughed up like it is and then just abandoned to nature. You have desecrated our lawn. Surely it can’t make that much difference to food supplies.’

‘While there’s still a shortage of food, the potato crop …’

‘Haven’t we given enough to this war?’

It was a funny thing to worry about: the rose garden.

‘Can you see to it for me?’ Mother continued. ‘I want the roses back. Perhaps ask Mr Tipton to send up old Alfred to lend a hand.’

Emily held her tongue. John had asked her not to argue with Mother, to pull together, to accept what had happened. She owed it to him to try her best. But he had also told her not to give up on what she wanted. He’d been certain that she’d find a way; but then he must have known that in the event anything happened to him it would make her escape even harder.

‘I’m glad I have you here, dear.’ Mother smiled weakly. Her head slumped in her hands. ‘You are quite impossible, but you’re all I have.’

*

Bishop warns against spate of hasty marriages

She was under the monkey puzzle tree, the newspaper resting on her knees.

Young people were getting carried away with romantic ideals and marrying when they’d only just met, the Bishop warned. A young man, a gunner with the army, spoke out against the Bishop. The gunner argued that the man of the cloth didn’t understand how war made every moment precious. He stated that the marriages weren’t hasty at all, but blossomed after couples wrote to one another for many months, becoming better acquainted in pen and ink then they ever would under the watchful eye of a chaperone.

So, Theo wasn’t the only one proposing out of the carriage windows. It had seemed so soon, well it was soon – she’d only met him that afternoon and he’d asked her to marry him. But they wrote letters often and she discussed things with him she’d never dream of sharing with anyone else. He was interested in her, he believed in her and he’d been such a great comfort to her since John had been reported missing. He was often the only beam of light in an otherwise dark existence.

Her gaze travelled through the jagged branches of the tree. The gunner in the newspaper was right; life was precious. John’s disappearance had taught her that. It was important to reach out and grasp whatever the Fates sent you.

*

January 1916

Emily and Cecil shared a birthday and so Cecil came home from university so they could celebrate as a family. She might have guessed that he’d cause trouble before they’d even got to the main course of their evening meal.

‘I’m going to ignore my call-up papers,’ he announced. ‘I won’t be fighting in the war.’

Emily let go of the spoon and it fell into the soup bowl. The Conscription Act had just been passed and all single men between eighteen and forty-one had to join up.

‘John’s news made up my mind,’ he continued. ‘I’m not going to fight this government’s war for them.’

‘Hasn’t what’s happened to John invigorated you, made you angry and want to fight?’ Emily asked. It certainly had fuelled her desire to do everything she could to help them win the war. If the allies lost, John might never come home. And yet Cecil was passing that opportunity up while she was left at home to take care of Mother.

Cecil cut her dead with a withering glance and addressed Mother, who had gone a deathly pale and hadn’t moved since Cecil first spoke.

‘Asquith has no right to force me to join up,’ Cecil continued. ‘I’m going to object on the grounds of my conscience.’

Emily shook her head; her brother was to become a conscientious objector. He’d witnessed what sort of response his views elicited at John’s leaving party. It was just like him to not worry about the consequences for the rest of the family.

‘In that case, perhaps you could stay here with Mother, so that I can go to work and do my duty to King and country.’

‘I don’t believe that it is my place to run into machine-gun fire so that the upper classes can cling to their position or the capitalists can prosper. That’s not duty, that’s madness.’

‘But what about John?’ Emily asked. ‘He’s a hero, and you will undo that if you bring shame on the family.’

‘I don’t want to hurt the family. If I could leave you out of it, and just pay the price myself, then of course I would. And I will tell you now, just how sorry I am for the trouble I’ll bring to you,’ Cecil replied.

‘Oh Cecil.’ Although it sounded as if she wanted him to go off and risk his life, that wasn’t the case at all. Nobody wanted their loved ones to fight, but for both of them to sit the war out was so unpatriotic. ‘You will let everyone down.’ Mother still hadn’t said a word. ‘Don’t you think our mother has suffered enough?’

Emily pushed her soup away. How would she explain to Theo that her brother was refusing to fight while he risked his life every day in the name of his country?

‘What you’re talking about is dishonourable, you know?’ she said. ‘If every man refused to fight then the war would be lost. Mother, you must tell him.’

‘If every man refused to fight,’ Cecil jumped in, ‘then there would be no war and our differences would have to be resolved peacefully.’

She dropped her head. This was just like Cecil. He would be impossible to convince otherwise, but he would listen to Mother.

‘This war is so unfair,’ she said, thinking of Theo out there, still cheerful and doing his best for his country. ‘But if we don’t fight against the Germans, they might come here and do to us what they did to Belgium. Have you thought of that?’

‘Do you want him to go and fight?’ Mother said.

Her mouth gaped open. Of course that wasn’t what she wanted. Cecil was never meant to be a soldier. He wasn’t much older than a boy. His skin was still soft; his face wasn’t that of a killer. One brother had been missing for months, what could she possibly gain from losing another?

‘That’s a terrible accusation,’ she replied.

‘Cecil, my darling boy.’ Mother carried on. ‘Are you really certain?’

The rasp of Emily’s breathing filled the room.

‘My mind is made up.’

‘Very well,’ Mother replied.

Emily jumped up. Was that it?

‘Your family will stand by you …’

‘Mother …’ Emily began.

Mother raised her hand to silence her. ‘We must respect Cecil’s decision and support him.’

‘And does it matter what I think?’ she said.

But as usual, Mother didn’t answer.

The village would turn against them. The reminders of their patriotic duty were everywhere; Kitchener’s finger pointing at them from his poster on the railway station wall. They would lock Cecil up, subject him to hard labour. Would they even accept her on the farm if Cecil brought this disgrace on them?

She wiped her tears away. It was too much: first John and now this.

‘I will stand by Cecil’s decision.’ Mother blotted her lips and then shuffled out of the room and upstairs to bed.

‘You are making life impossible for me. Mr Tipton is desperate for help on the farm, and yet Mother insists I’m by her side, day and night.’

‘You spoke to me of duty, well Mother is yours.’

‘This might well break her, you know. Do you even care?’

‘Of course,’ he said, his voice breaking. He uncrossed his legs and stood from his seat. Had he even stopped to consider their financial troubles? Did he care that without John at the helm Mother would continue to take handouts and do nothing to resolve the root of the problem?

He was crying now. Huge tears dripping onto the tablecloth. His decision would bring him enough grief – she couldn’t add to it. She comforted him, put her arms around him. He was a pitiful sight stooped over with his nose streaming. He was electric to touch as if he exuded the toxic danger that he brought to the family.

He stepped out onto the lawn, towards the monkey puzzle tree, swung back his arm and punched the trunk. He lifted his face to the heavens and opened his mouth, but from inside the dining room his yell was silent.

Chapter Nine

February 1916

Mrs L Cotham

HopBine House

New Lane

Chartleigh

Kent

The envelope sat on the mantelpiece for an entire morning, peeking out from behind the photograph of John in a frame painted with forget-me-nots. Finally, the three of them – Emily, Mother and Cecil – gathered in the sitting room. Emily took the opener and slashed open the envelope.

The War Office had completed its investigations and Officer John Cotham was now officially regarded as having died.

Her mother whimpered. Cradled her face with her hands.

‘No wonder Kitchener wanted bachelors.’ Cecil’s bottom lip trembled as he spoke.

Emily tumbled into a long, black tunnel that stretched to eternity; the same tunnel she’d fallen into when her father had died. No matter how far she fell, the dark hole stretched into the shadows. Her legs were filled with a substance as heavy and clogged as the mud Theo described in the trenches. She’d wanted to hide in her bedroom until someone came to tell her it was over, that it wasn’t true. But Mother needed them both. She wept uncontrollably as if there was no room in the house for her or Cecil to grieve as well.

When friends and neighbours called on them, Mother put on a show.

‘I’m but one of thousands of mothers in the same position.’

Privately, Mother fretted, ‘Would I have treated him differently as a baby had I known?’ Her food went untouched. She paced about the house in the dead of the night, wept until her throat was sore and winced as she swallowed her tea. Worst of all, she became fixated with John’s whereabouts. In a husky voice, she speculated that the War Office had got it wrong. Perhaps they’d confused him with another man.

‘It must be difficult to keep track of them all, so many men, scores missing or killed.’

Then one of the sets of John’s identity tags was returned to them in the post, along with the diary full of the names of the men he had lost in battle. The officer uniform that they had paid for arrived wrapped in brown paper.

Emily flicked through the pages, pressing her fingers to the inked names, and then at the very last page, at the end of the list she added one last soldier:

John Cotham.

And then she added his service number after his name.

Emily encouraged Mother to write to an old friend of her family. Lady Heath had been widowed when her husband had been killed on the first day of the Somme in 1914. Lady Heath wrote back suggesting that her friend make a remembrance book. Mother pasted in photographs, letters, press cuttings and John’s identity tags. Lady Heath shared the poetry she had written about her husband, but Mother said she just didn’t have the words.

There was nothing that she could do to reach her.

The letters and bills piled up in the library, but Mother wouldn’t allow her to open them.

‘We can’t ignore our problems forever,’ Emily insisted. ‘We will have to do something.’

Despite the lack of sleep and loss of appetite, Mother rapped the glass with her fists and yelled that the vegetable garden needed to go. Emily agreed for once. Her hopes of doing any war work had died with John and the plot was a cruel reminder, but even so it was one of the last things she’d done with her brother and she couldn’t let it go back to the roses yet.

Desperate to soothe Mother’s grief, Emily suggested a memorial service.

‘We could hold a service at the church, followed by a wake on the lawn.’

She had to do something to help Mother find her strength. She still couldn’t believe it herself, and dear John deserved a fitting tribute. The problem was Cecil. Now that word about his conscientious objection was travelling around the village, they might be alone at the service. The memorial might be for John, but it could end up being about Cecil.

*

March 1916

Emily rushed down to the hallway as the front door slammed shut.

‘No good,’ Mother said, tossing her gloves onto the hall table, her voice still hoarse. She barged past Emily and Daisy on her way to the kitchen.

‘What did they say?’ Emily cantered to keep up with Mother.

‘They were a bunch of jumped-up old has-beens dizzy on the power bestowed upon them by the Crown. It could hardly be called a hearing, because Cecil wasn’t heard at all. They didn’t even let him speak. Not once.’ She paused to clear her own throat. ‘He had written a stirring and powerful speech in defence of his principles.’

Mother searched about her, opening cupboards and slamming them shut. The servants’ indicator board behind her was a reminder that they were on the other side of the house now.

‘They imprisoned him there and then.’

Emily gripped the kitchen table. First John, and now Cecil, gone within a matter of weeks.