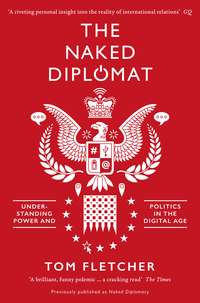

The Naked Diplomat: Understanding Power and Politics in the Digital Age

Diplomacy also started to take root elsewhere. In Egypt, following the battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC, Pharaoh Rameses II and ruler of the Hittite empire Hattusili III created the first known international peace treaties, on stone tablets.4 Some of the covenants in these early treaties bear a strong similarity to the Ten Commandments that Moses was given, probably between the fourteenth and twelfth centuries BC – a fairly one-sided diplomatic treaty between God and Man. The messenger was not always welcome. The Bible records envoys of King David having their heads shaved and buttocks exposed by an unimpressed monarch – a punishment self-imposed by many modern football fans when travelling overseas.

Rival Chinese states in the first millennium BC started to draft more detailed treaties to enforce conquest and avoid unnecessary conflict. Others in Asia, such as the Japanese and Koreans, drew from this example, including by establishing temporary embassies. Records remain of Chinese Song dynasty ambassadors who were able to outfox opponents through guile and cunning rather than force. Theories of human interaction, such as Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, demonstrate how leaders spent an increased amount of time considering how to subdue their enemies without the cost in blood and treasure of fighting them. As the Chinese empire expanded by sea from the second to thirteenth centuries AD, they sent resident envoys as far afield as India, Persia, Egypt and Africa, often despatching two – as they did to Japan in 653 – in case one never arrived, as was all too often the case. It must have been interesting when both did.

By the time the Chinese invented gunpowder in 900, they had already used diplomacy to create an empire so large that they did not have to use the gunpowder as an instrument of warfare and statecraft. If they had done so, as the Europeans started to do to such devastating effect in the fourteenth century, all our treaties and diplomatic language might now be in Chinese.

In Europe, meanwhile, the first Greek city states also found a need for diplomats to negotiate with rivals and allies. The basic rules and conduct of diplomacy they adopted in the Congress of Sparta in 432 BC were a template for much of the diplomacy of the next twenty-two centuries until the aftermath of Waterloo. The Spartans, in a sign of extreme confidence, even invited the adversaries – the Athenians – that they were considering attacking.

The Greeks tended to send diplomats on short missions rather than making them resident in other countries. Heralds would venture out to pass messages and to report back, if they had not been executed, on the quality of the reception they received. The forefather of the modern consul, often a resident of the city who happens to have a particular link to another, can be found in the Greek proxenos, who acted as informal sources of information and message carriers.

It was the Mongols who first put diplomacy on a more sophisticated footing. In 1287, Prince Arghun sent the first embassy to the West under Rabban Sauma, an elderly monk turned diplomat, as part of his effort to form an anti-Muslim alliance against Syria and Egypt. He promised the French the city of Jerusalem, and generously suggested that he would be ‘very willing to accept any samples of French opulence that you care to burden your messengers with’. He even tried to broker an accord with the distant Edward I of England. But Europe, or the Vatican at least, was clearly well behind their Mongol visitors – Sauma reported back that he was underwhelmed by the ‘lack of worldly intelligence among the cardinals of Rome’.5

As communication, travel and trade developed, it became necessary to establish rules for diplomatic interaction that went beyond protocols on exchanges of gifts. Like the Japanese, the Byzantine and Sasanian (modern Iran) leaders took the precaution of sending messages with two envoys in case one was lost or misplaced in unforgiving new environments. In the thirteenth century, the Mongols took this idea further and developed a new form of diplomatic passport, granting their envoys special status and protection. Genghis Khan, a historical figure usually more associated with ending rather than protecting lives, introduced diplomatic immunity. For messengers to do their job, it helped that they occasionally returned intact. That principle remains in place today, thankfully.

Six hundred years ago, it was the East that could claim to be the centre of diplomatic understanding and political power. But an unknown goldsmith in Strasbourg was about to change everything.

2

Diplomacy By Sea: From Columbus to Copyboys

At the beginning of the age of European maritime discovery, the Chinese were ahead of the West in almost every respect, not just diplomacy. In 1492, Christopher Columbus set off to discover the Americas with ninety men in three ships. His closest Chinese equivalent, the intrepid eunuch Admiral Zheng He, had an armada of 300 ships, a compass and 27,000 men (including 180 doctors and several envoys). Columbus’s biggest hull was barely twice the length of one of Zheng’s rudders.1 This hard-power advantage meant that many of the earliest diplomatic protocols and customs were more Eastern than Western. To this day, diplomats are scathing of colleagues seen as ‘kowtowing’, a deep and humble bow, to representatives of other nations.

Despite this head start for China, Europe took the lead in the centuries that followed, in diplomacy as in harder power. Maybe peninsulas made it easier for small kingdoms to hold out against potential conquerors.2 Europe might have had an advantage in this era of climate, topography, resources, culture, politics or religion. Or perhaps it was simply down to short-term accident and chance.3

The Chinese had invented the first newspaper in 748. But German inventor Johannes Gutenberg’s creation of the movable-type printing press in the 1440s allowed humans to capture more accurately and share more widely the most important lessons of their ancestors. We no longer relied on oral histories alone. This created an extraordinary platform for innovation, and more time to explore and create. Gutenberg was the Tim Berners-Lee of his age, generating unprecedented access to knowledge.

Within two generations, Columbus and others were leading the Age of Discovery. When Columbus returned from the Bahamas, eleven print editions of his journey spread around Europe. Within twenty-five years, sailors had circumnavigated the globe, and the Reformation was under way, on the back of the production and distribution of millions of Martin Luther’s pamphlets. Merchants and farmers alike began to question the absolute rule of monarchs, and the political fundamentals of society. There was a new thirst for knowledge, stimulating the Enlightenment, the American Revolution and free-market capitalism. This print revolution contributed to the formation of modern nation states, and therefore the diplomats to represent them. The spread of information in shared languages stimulated the emergence of common and competing national identities. These new European nations – Germany, France, Austria, Russia – needed people to understand their differences, and to mediate between them.

As the Europeans closed the gap on their global competitors, they sought new ways to protect and project their advantage. One manifestation of power was the man on the spot. The first more permanent embassies, expressions of ambition and influence, were started by the states of northern Italy during the Renaissance, with Milan the trailblazer. Cosimo de’ Medici (1389–1464) became the first semi-permanent ambassador of the city in 1450. Backed by enormous personal wealth, he helped to create a balance of power between his native Florence and the leading Italian city states. He even took his own bank with him, a luxury sadly but sensibly denied by modern treasuries to their diplomats.

Wars are of course another powerful tool for domination, and the Renaissance had plenty of them. But they are also disruptive and costly for leaders. Increasingly, princes wanted people who could build their influence in other ways. They needed local intelligence, and eyes and ears on the ground. Milan sent the first ambassador to the French court, in 1455, and Spain despatched the first permanent representative, to London in 1487. These tended to be noblemen, able to finance the lavish lifestyle meant to come with the territory. An embassy came to mean a physical presence rather than a formal visit.

Advisers such as Machiavelli began to build a theory of power around this work. These early envoy roles were sought-after positions held by the talented innovators and explorers of the age. Men such as Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio were among the first envoys of Florence. This is like making Damien Hirst, Sebastian Faulks and Ian McEwan Britain’s ambassadors today. For these early envoys, diplomacy was not a career but a pursuit, one that reinforced their social position and cultural instincts. Early forms of the word ‘ambassador’ – ambaxade, ambasciatore, ambaxada – seem to have derived from ambactia, meaning charge or office. Or perhaps ambactus, servant. Even at its well-heeled origins, I like to think that there was a sense of public service to the description.

Inevitably, an informal network of travellers and messengers became more structured. Leaders needed to know that the man in front of them – and of course in this era it always was a man – was really representing his prince. So the tradition of presenting credentials on arrival, which continues to this day, began.

Many diplomats are still communicating with their host government and their own capital using these gloriously archaic instruments. On arrival in a country, the ambassador is not meant to meet anyone officially until he has presented his credentials to the head of state, a process that can often undermine his impact during the most important period. While the private sector focuses on the first ninety days of a CEO’s tenure, the ambassador often spends their first weeks marooned in their house, unpacking and waiting for permission to hand over a piece of paper. When it comes, the ceremony can be moving and memorable – the hairs on the back of my neck stood up when I listened to the British national anthem at the president’s summer palace high in the Shouf mountains of Lebanon in August 2011. But the protocol gets in the way of real diplomacy.

Much of the language remains more Renaissance than Digital Age. Here is an extract from my credentials, which perhaps shows that modern diplomats have not travelled as far from our lace-cuffed predecessors as the smartphones in our pockets suggest:

To All and Singular to whom these Presents shall come, Greeting!

Whereas it appears to Us expedient to nominate some Person of approved Wisdom, Loyalty, Diligence and Circumspection to represent Us in the character of Our Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary at Beirut; Now Know Ye that We, reposing especial trust and confidence in the discretion and faithfulness of Our Trusty and Well-beloved Thomas Fletcher, Companion of our Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George, have nominated, constituted and appointed as we do by these Presents nominate, constitute and appoint the said Thomas Fletcher to be Our Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary at Beirut as foresaid.

Giving and granting him in that character all Power and Authority to do and perform all proper acts, matters and things which may be desirable or necessary for the promotion of relations of friendship, good understanding and harmonious intercourse between Our Realm and the Republic of Lebanon and for the protection and furtherance of the interests confided to his care; by the diligent and discreet accomplishment of which acts, matters and things aforementioned he shall gain Our approval and show himself worthy of Our high confidence.

Terrific stuff, but hard to tweet.

The letter of credence was established to show that an envoy was genuinely representing his state, when there were not other ways to check thoroughly. That’s now easier to establish. Credentials can be replaced by a Google search.

Not every historical leader appreciated the new customs either. When Anthony Jenkinson, a sixteenth-century trader, traveller and envoy of Elizabeth I, tried to present credentials to the cosmopolitan Persian emperor Shah Tahmasp, he failed to wear the slippers offered to cover his infidel feet, was thrown out of Isfahan and his footprints back to the port covered in sand. He was Photoshopped out of Persian history.

As the number of diplomats attached to royal courts grew, they inevitably began to compete for attention and influence. With their masters jostling for power and prestige, diplomats in European capitals were ranked on the basis of the power of their monarchs, a fiendishly complex and contested process. This rivalry consumed much of their energies, and would strike terror in the heart of the modern diplomat less used to having to compete so overtly for attention and influence.

According to Samuel Pepys, the Spanish and French embassies in London frequently came to blows in the 1660s over breaches of such protocol and ranking. Asked where he would like to sit at a dinner with the English king, Charles II, the French ambassador answered: ‘Discover where the Spaniard desires to sit, then toss him out and put me in his place.’ I admit that I have attended many diplomatic dinners where such dark thoughts have crossed my mind. But fortunately for less adversarial modern diplomats, ranking is now based on your date of arrival in post.

Another account describes how, during the 1661 arrival of a new Swedish ambassador to London, the French coach (with 150 men, forty of them armed) clashed with that of the Spanish ambassador, similarly tooled up. The Spaniards killed a Frenchman and took down two French horses, forcing the French to reluctantly cede the second position in the procession. Louis XIV of France was so incensed that he told his Spanish counterpart that he would declare war if there were ever to be another such breach of protocol.

But such clashes continued – in 1768, the Russian and French ambassadors to London duelled following a dispute over who should sit where in the diplomatic box at the opera. The modern equivalent is the competition to be seated next to the US president at international summits. Alphabetical orderings can often be the most diplomatic solution. At these moments, British diplomats tend to favour the use of ‘United Kingdom’ over ‘Great Britain’. It gets the leader closer to their American counterpart, and safely clear of the difficult group of countries whose names begin with ‘I’.

Diplomacy can both thrive and suffer in times of intrigue and change. The cold war that followed the Reformation set back the process of statecraft, with Catholic or Protestant ambassadors frequently seen, with some justification, as the centres of intrigue and espionage in rival courts. Yet it forced those envoys still allowed to lurk behind the curtains of those courts to make their communication with their capitals more cunning, and increased their value to their masters.4 In the 1630s, Cardinal Richelieu, one of Louis XIII’s most infamous and effective ministers, wrote of the need for ceaseless negotiation, even when – in fact especially when – no fruits are reaped. After 1626, he established a Ministry of External Affairs to centralise the management of foreign relations under a single roof, and – perhaps most importantly to him – to control the information reaching his king. The practice was soon followed all over Europe. A picture of the ‘Red Eminence’ should be on the wall of every modern ministry of foreign affairs.

Maritime expansion by the early European empires created the need for further rules and negotiation, not least because failure to observe increasingly complex protocol could trigger conflict. Elizabeth I was clearly a sharp and perceptive observer of diplomatic vanity, and banned her ambassadors from accepting awards or insignia from other nations – ‘I would not have my sheep branded by any mark but my own.’ The tradition continues to this day, though it is explained to sensitive diplomats in gentler terms.

Diplomacy was increasingly the arena in which to play out wider competition for respect, with failure to observe basic courtesies taken as great insults to a monarch’s dignity. When the Spanish ambassador to the English court of James I refused to dip his colours to his host in the early seventeenth century, the ensuing diplomatic furore nearly triggered a second armada.

Most European envoys sent east had a more commercial brief. British diplomat Anthony Jenkinson, having recovered from his undignified exit from Persia, reported back to Elizabeth I that his 1557 Christmas dinner with Tsar Ivan IV Vasilyevich had laid the foundations for a potentially lucrative trading relationship. Clearly there was no Elizabethan human rights lobby to suggest that emperors who called themselves ‘Terrible’ and had been executing rivals since the age of thirteen might not be appropriate commercial partners. Another envoy, Thomas Roe, recorded having avoided offending the Mogul of India by accepting an attractive female concubine for the duration of his stay, ‘in order to comply with custom’ (an excuse that probably would not work today). Competition between these early European merchant envoys was fierce and the penalties severe – the Dutch tortured eighteen British traders to death in the East Indies in 1623.

Yet, necessary concubines aside, the job of Elizabethan envoys was in many ways recognisable. Sir Jeremy Bowes was the ambassador sent by Elizabeth I to the court of Ivan the Terrible following Jenkinson’s convivial, and clearly successful, Christmas lunch. Apart from staying alive, he had three jobs: to assert the authority of his queen as the equal of the tsar, to obtain important commercial contracts for British merchants, and to establish a commercial office in Vologda. His successors in Moscow today are working on similar projects. Bowes also had to free a British widow whose Dutch husband had been roasted to death, a consular case that is happily less likely to arise in today’s embassy.

The first pioneering diplomats were not setting out across continents on some kind of grand tour or glorified gap year, but to seek new resources and trading opportunities. In the age of maritime diplomacy, consuls would mediate between ships from their countries and port authorities to ensure market advantage. Schoolchildren still learn that ‘trade follows the flag’. But diplomatic history also suggests that the flag often follows trade – the business lobby needed a British embassy in Constantinople in the sixteenth century, and so the Levant Company funded it, an association that continued until the early nineteenth century.

Diplomacy has always had a strong mercantile core, although in recent decades commercial work has tended to come in and out of diplomatic fashion. It was placed at the centre of the British Foreign Office’s priorities after the First World War and in the 1970s. The British post credited with making the best commercial effort in the 1970s was Tehran. They responded to instructions to focus embassy time and resources on supporting business links with Iran. This came at a cost: they were late to spot the warning signs of the overthrow of the shah.

Diplomats tend to enjoy trade promotion because it is more tangible than other elements of their roles. It is hard to measure warm bilateral relations, or the extent to which lobbying on climate change shifts a host government’s position. But a contract with numbers stands out.

So what do businesses want from diplomats? They want hard and relevant political analysis, a good contact book, and the willingness to use it. Businesses know that diplomats can get the right people around the table.

But there are also risks. Diplomats can lose their objectivity about where the national interest lies, and the balance between commercial priorities and our wider equities. This particularly applies to diplomats who would like to make some money themselves at some point, as many will increasingly need to do. Traditionally, the revolving door was more of an exit door. Senior diplomats left their foreign ministries to get highly paid jobs on the boards of oil companies, banks and arms manufacturers.

Increasingly that model will change – diplomats will more often leave in mid career, harassed by spouses angry at the impact of regular moves on family life; needing a financial cushion; and seeking new experiences and oxygen. This is healthy, increasing the pool of diplomats who have tried other professions, and who are flexible and marketable enough to adapt, learn and return. The downside is that it will undermine the sense of diplomats as a cadre, and blur the lines of accountability further. As austerity bites and diplomats get paid less, they risk becoming more reliant on business to keep the ship afloat. This is not easy for modern diplomats, any more than it would have been for the British consul in sixteenth-century Constantinople.

An awkward but unavoidable question for diplomats will be the extent to which we sell our services. The British Foreign Office already hires out ambassadors for commercial events. I’ve made speeches on subjects ranging from ceramic water filters to ornamental garden gnomes. It is a small jump from this system to one where we offer a commercial service for our insights. None of us would want to see diplomacy become too mercantilist or commercial, but the economic realities may dictate that there is no choice.

Diplomats gradually developed a sense of their own craft. As diplomacy took root as a profession, it was codified, analysed and described, mainly by French diplomats. In 1603, Jean Hotman de Villiers (1552–1632), an Oxford professor who led diplomatic missions for Henri IV, produced a guidebook for ambassadors, De la Charge et Dignité de l’Ambassadeur. Abraham de Wicquefort (1598–1682) was a Dutch envoy and spy who, after playing a central role in producing the Treaty of Westphalia, was found guilty of treason. Imprisoned in the water castle of Loevestein, he wrote the huge L’Ambassadeur et ses Fonctions in 1681. This became the handbook for seventeenth- and eighteenth-century diplomacy, and was based on real-world examples of his craft. Much of it stands the test of the time, including his advice that ambassadors need to combine the theatre of their public role with the discretion and often secrecy of their private negotiations. Loevestein was clearly a good place to think big. Another political prisoner was Hugo Grotius, often seen as the father of modern international law. More notable, for diplomats anyway, he went on to become Swedish ambassador to France. François de Callières (1645–1717), a diplomat for Louis XIV, analysed European diplomacy in his 1716 book De la Manière de Négocier avec les Souverains. He agreed with de Wicquefort that the ambassador had to be a good actor.

Diplomats also needed to stay in closer contact with their capitals. When envoys began to create too much information to pass by hand or official messenger, they instigated a mail service for handwritten correspondence, and a Postal Convention (of 1674) to try to protect confidentiality. Documents began to be transported by the more formal system still in use today, the diplomatic bag. This was meant to guarantee that messages between an embassy and its capital could not be interfered with by the curious or hostile. Naturally, this was usually ignored in the atmosphere of intrigue and mistrust surrounding the wars of religion.