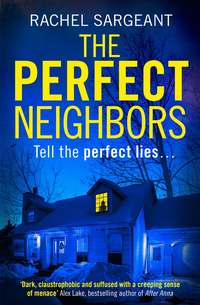

The Perfect Neighbors: A gripping psychological thriller with an ending you won’t see coming

Before Helen could ask what he meant, Louisa tapped a spoon against her glass. Everyone fell silent and she made her announcement: “It’s super to see you here to greet our newest arrival, Helen. Please join me in giving her a traditional Niers School welcome.”

The guests erupted into applause. It was like being received into a religious cult. Helen’s glance stayed on the parquet floor until the ovation subsided. When Louisa stopped clapping, the others did too.

“And now the boys are going to perform for us,” Louisa said. “Toby has been begging me to let him play ‘Kalinka’, haven’t you, Toby?”

Toby gave a bemused smile and opened the door beyond the dining table to the music room. Out bounded an enormous polar bear of a dog. It sniffed round the assembled guests, its wagging tail slapping their legs. Mel Mowar gulped and backed into a coffee table.

Louisa grabbed the dog’s collar and pulled him across the floor. “For goodness’ sake, Mel, you know Napoleon won’t hurt you. He’s just being friendly. Everyone, go through to the music room.”

Mel’s breathing sounded erratic, but no one paid her any attention, not even her husband Chris.

“Shall we go through?” Helen whispered to her.

Mel gave a relieved smile.

The tiny music room was kitted out with an upright piano, a bookcase of music scores and now three small boys, sitting behind a cello, violin, and tambourine. As the guests squeezed in, the smallest boy waved his tambourine at them.

“Murdo, don’t play until I nod,” Louisa told him.

“Noh, noh,” the boy said.

Helen decided he was younger than he looked, and cute. She smiled.

Louisa’s elegant fingers glided over the keys. It was obvious that Toby hadn’t begged to play the piece at all. She’d chosen it to show off her musicianship.

Helen glanced at the bookcase, at the TV in the corner, at the other guests in the cramped room – anywhere to avoid watching the self-satisfied expression on Louisa’s face. There was a small window out onto the garden. Something caught her eye at the back fence. A dot of orange light and a dark, moving shape. She squinted hard for a better look.

When Louisa tackled a tricky chord, Jerome Stephens stepped forward to applaud and obscured Helen’s view of the garden. She tilted her head and saw elbows and hands on the back fence. A face appeared, spat out a cigarette and vanished.

She was about to warn her hosts, when Toby came in on the cello. It would be rude to interrupt the child; she’d wait until the end. She’d expected him to be rubbish, assuming that Louisa was a deluded, selectively deaf mother who couldn’t hear the screeching tune being murdered on the half-size instrument. But Toby could play. He wasn’t Jacqueline du Pré but he was better than the kids who performed solos at the school where Helen used to teach. And they had been teenagers; this was a boy of eight. When he finished she clapped as enthusiastically as the other guests.

Louisa announced that they would play the last part again so that Toby’s brothers could join in. She hit the piano keys harder this time. Leo, the middle child on the violin, hadn’t inherited his brother’s talent. Napoleon retreated to the dining room to escape the highpitched whining. Louisa nodded at Murdo but he continued chewing his tambourine. He joined in the applause at the end.

“Why didn’t you play, Murdo?” Louisa asked. “Didn’t you see Mummy nod?”

Damian ruffled his youngest son’s hair. “It doesn’t matter, matey. Let’s have supper.”

Helen opened her mouth to tell them about the intruder, but the view from the window was serene and the idea seemed ridiculous. Had she really seen someone on the fence? It was getting dark outside and she was two glasses into the Howards’ quality champagne. When she saw Gary looking at her quizzically, she smiled and followed him into the dining room.

She was sure of two things: Louisa would seat her as far away from Damian as possible and she’d end up next to Mel’s husband Chris. She was right on both counts. Chris was to Helen’s right and beyond him was Polly, still holding her baby alarm. Louisa took her place at the head of the table, on Helen’s left. Damian was at the far end, but still managed to smile in her direction every time she looked up. She found herself blushing.

When Chris put down his glass and asked, “So, Helen Taylor, tell me about yourself,” she didn’t want to answer. There was something unnerving about him, as if he might use whatever she said against her one day.

“Not much to tell. What about you?” she said. “What do you teach?”

“I’m head of A and D. That’s Art and Design. Hardly rocket science but it passes the time until my project is complete.” He faced her but raised his voice to address the whole room. “Have you heard of Michael Moore?”

Before she could answer, Louisa leaned forward. “He’s an American documentary maker. Chris intends to follow in his footsteps.”

Chris shook his head. “Louisa, my darling, a Chris Mowar Production doesn’t follow. What I’m working on will turn the documentary film industry on its head.”

“Chris has a big plan to expose con men but I think it’s been done before,” Louisa said, looking at Helen.

“Not with the treatment I’m giving it.” Chris tapped the side of his nose. “It’s all about the long haul. Con men take their time to exploit people’s weaknesses. They’d exploit yours,” he said, leaning back in his chair and staring at Louisa.

“How droll you are,” she said and gave a forced giggle.

Chris stretched out his arms. “Take this room, for instance, with its statement yellow wallpaper.”

“It’s savannah and gold. What about it?”

“Whatever you want to call it, it’s not school-issue. You’ve practically rebuilt this house from the inside out. A con man could send the whole thing tumbling down.”

Louisa didn’t reply. She concentrated on picking a crumb off the table and depositing it on the side of her plate. The only sound was Napoleon chomping on his bone under the table.

“So, Helen, what do you think of our little neighbourhood?” Damian called down the table. She wondered if he was asking to deflect the spotlight from his wife. But Helen was now the one feeling the heat. Polly and Jerome looked at her. Louisa was watching too.

“It’s delightful,” she said, banishing parochial from her mouth.

“This street is a real community, like Britain in the 1950s,” Damian said.

“Even though we have some foreigners in our midst.” Chris laughed.

“Poor old Manfred,” Polly said, moving the baby alarm nearer to her plate. “He must miss his cottage.”

“He was jolly lucky the German Government gave him a house in perpetuity. We get our rented houses but once we leave the school we’re on our own,” Jerome said.

“But isn’t that the point?” Polly replied. “He was given that house for life. Whatever the rights and wrongs of that arrangement, the school shouldn’t have demolished it.”

“I think we’d better explain to Helen,” Damian said. “Manfred Scholz lives at number 2. He’s our groundsman – looks after the school site. One of the perks of the job was his own cottage inside the campus. We wanted the land to build a new gym so he and his wife had to be re-housed in Dickensweg.”

“He’s a super chap. Dignified,” Jerome added. “But probably time the old boy retired.”

“He’s been lonely since his wife died but I do what I can to include him,” Louisa said.

Chris folded his hands behind his head. “If you ask me, he’s no lonelier than he was before. With all that obsessive cleaning, the only way to get attention from a Hausfrau is to lie on your back covered in dust.”

Helen was shocked at the open insult to the German locals. She glanced across the table to Gary. He stopped smiling and winced. She thought it was apologetic; it damn well ought to be. What kind of neighbourhood had he brought her to?

After dessert, Louisa took coffee orders. Helen stacked the plates and followed her into the kitchen. The room was space age: white units, black granite tops, built-in cooker. She opened the bin to scrape the plates and saw a heap of hot cross buns at the bottom. So that’s what Louisa thought of Mel’s food offering.

“Where shall I put this?” Mel appeared with leftover gateau.

“Bio bin,” Louisa said.

“I’ll do it.” Helen took the plate from Mel to prevent her seeing inside the bin.

Jerome came in to say goodbye; he was leaving before Polly to be with their girls. When Helen went back to the dining room, there was no sign of Gary, Damian, or Chris.

“They’ve gone to the den, in the cellar,” Louisa explained. “It’s very much Damian’s lair; it stops the men making the lounge untidy.” She gave a little giggle. It sounded like a hiccup.

She invited the women into the lounge but didn’t ask them to sit down. As if at some late-night cocktail party, they stood in the middle of the room. Helen longed to sink into one of the cream sofas which beckoned her like a bubble bath. The herbal scent that she’d encountered in the hallway was stronger here.

Louisa noticed her sniffing. “It’s lavender. I’ll give you a sample before you leave. I’m a qualified aromatherapist, but only work part-time now that I’m chair of the Parents’ Association and on the Board of Governors.”

“I don’t know how you do it all,” Polly said.

“I try,” Louisa said and smoothed down a chiffon sleeve.

Helen glanced at her watch. Midnight. How much more of Superwoman could she endure? She excused herself to go to the loo and went to find Gary.

***

The cellar in Gary’s house was about as attractive as a multistorey car park, but when she stepped over Toby’s school bag and descended into Damian’s den it was like heading into a nightclub. Red tiles on the walls and another wooden floor. The first room was decked out like a cinema with a huge flat-screen TV, easy chairs, and a popcorn machine. She could hear the men in the room beyond. As she approached, she heard Chris’s voice.

“You need to lighten up, mate. Club Viva’s in the past. What’s done is done.”

And Gary’s reply, “Steve texted me again.”

They were standing around a pool table, holding cues. Gary rubbed the bridge of his nose.

They looked shocked when they saw her, as if she’d caught them in the act of something. Was it because a female had invaded their beer den, or something else?

Gary coughed awkwardly. “Are you ready to go, love?” he asked, resting his cue against the wall. “It’s time we called it a night.”

Whenever they caught up with friends in England, he’d party into the small hours until she dragged him away. But tonight he seemed ready to leave his colleagues. Maybe he wasn’t as fond of his neighbours as she’d assumed. The thought of how in tune the two of them were was exhilarating. She couldn’t wait to get him home.

***

They made love for the first time since her arrival and she fell asleep in his arms. She woke in the night. Was Louisa at the bloody door again? But it wasn’t the doorbell; it was a staccato tapping noise. Her mind flickered to the face at the Howards’ back fence. An intruder? No, she was being hysterical. The sound must be from next door; Gary had warned her that the walls between the two semis were thin. Chris must be filming night shots for his documentary.

But the sound was coming from their spare bedroom, the one Gary had set up as a study. She realized she was alone in the bed.

“Gary?” There was no one else in the house to disturb, but she whispered as she went to him. In the light of the computer game on the screen, he looked grey and there were hollows under his eyes. He was hitting the hand-held controller with his thumbs.

“You’ll be wrecked in the morning. Come back to bed,” she said.

He jumped when she spoke. “Sorry, I forgot you were here.” He sighed and rubbed his eyes.

He’d got up both nights since she had arrived in Germany; now he didn’t even remember she was there. “Are you happy about us living together?”

He reached out for her arm. “How can you even ask that? It’s what I’ve wanted ever since we got married. I can’t sleep, that’s all. It’s nothing that you’ve done.”

“You looked serious in Damian’s cellar tonight,” she said. “What were you talking about?”

“Can’t remember now. Politics probably. Men don’t only talk about football you know.”

“What’s Club Viva?”

In the light of the computer screen, Gary’s face grew paler. He thumbed the games controller, ignoring her question.

“Gary?”

“Actually that was football talk,” he said and forced a chuckle. “You caught us out. Did you enjoy the evening?”

“Polly and Jerome were nice,” she conceded. “And Damian was friendly.” She thought of his lingering smiles across the table. Too friendly maybe. “Is he a bit of a, you know, wanderer?”

Gary’s eyes shot up from the computer screen. “How would I know?” He sounded defensive, then he shrugged. “Why would he play away when he’s got Louisa? She’s great, isn’t she? What did the two of you talk about?”

Helen sighed. “I listened more than talked. Are you coming back to bed?”

“I’ll just finish this,” he said, a desolate look in his eyes.

Fiona

“You’re on the home straight now,” Dad said. “Come July we’ll have a graduate in the family.”

He lifted my heavy suitcase onto the bed and winced, letting out a sharp breath.

“Sssh, Dad, don’t tempt fate.” I put my arms round his neck and kissed him, pretending not to notice the twinge when I pressed against his chest.

Mum found some wire coat hangers in the empty wardrobe and opened the suitcase. “I wouldn’t be surprised if you get an Upper Second. Your French is so good after your year in Lyons.” She started putting my clothes on the hangers.

“Thanks, Mum, but how do you know? You don’t speak French,” I said, taking over the unpacking.

She kissed me on the nose and we giggled.

Dad rattled the bookcase. “You’d best put your big books on the bottom so it doesn’t wobble over.” He walked to the window. “Nice view of the bins.”

Mum joined him. “She doesn’t need a view. She’ll either be working or sleeping when she’s in here.”

“How far is it to the student bar?” Dad said, standing on tiptoes to peer out. “We could check out the route with you before we go.”

“No, thanks,” I said quickly. I wasn’t in with the in-crowd at the best of times, but arriving at the uni bar with my parents would make me the uncoolest student outside the computer science faculty.

“Do I take it you want your personal chauffeurs to hop it before we damage your street cred?” Dad said. He was smiling, but there was that penetrating twinkle in his eyes. Even when he’d been ill he had kept his unerring ability to read me like a kiddies’ comic.

I hugged them both, breathing in the smell of them.

“See you at Christmas,” Mum said.

We hugged again, not knowing that Christmas would never come.

4

Monday, 12 April

Gary pecked her on the neck, shoved a slice of toast in his mouth and headed for the kitchen door.

“I was thinking I might paint the lounge this week. Any preference on colour?” Helen called after him.

He came back in. “Up to you as long as we paint it back to magnolia if ever we move out.”

“What about the Howards’ house? They’ve virtually taken a bulldozer to it. Will they have to put it back when they leave?”

“Eventually. I don’t know who the landlord is – some German Herr Money Bags no doubt – but we have to leave things as we find them. I can’t see Damian quitting Niers International in a hurry. Where else would you have every child’s dad in full employment? A bit of a difference from the comp you worked in.”

Helen said nothing but wanted to point out he’d never been to her school. Shrewsbury Academy had more than its fair share of success stories.

“Number Ten is something, isn’t it? Louisa has a real eye for design,” he said. “You could try a bit of painting if you want to.” He gave her another peck and left.

Helen dropped the breakfast pots in the sink and wondered what she could do that wouldn’t involve an unfavourable comparison with the decor queen across the road.

She and Gary had spent the previous week like tourists: Cologne Cathedral, a boat trip on the Rhine, and Kaffee und Kuchen in several chintzy cafés. Days wrapped in the mist and drizzle of a North German spring, but burning with the same light as their Jamaican winter honeymoon. They’d discovered the Caribbean together, but here Gary was her personal guide, showing off, proud and impatient for her approval. And she’d given it, teasingly at first, watching uncertainty flicker in his eyes before letting her kiss reassure him.

She pointed the tap at the dirty plates. Her mind wandered to the welcome briefing she’d endured the previous Friday. The school employed a nurse, a smart, thirty-something German woman called Sabine, who doubled as the staff and pupil welfare officer. She’d invited Helen and two new teaching assistants into her treatment room. Helen sat between the two gap-year Australians, facing a medical examination table. Above it was an instruction poster on how to conduct a smear test.

Over instant coffee and custard creams, Sabine told them, in her impeccable English, about registering with a local doctor and what school facilities they were entitled to use. When Helen had asked when the school swimming pool was open to staff and families, Sabine shook her head. “It’s only for the children. The nearest indoor swimming pool is over the border at a Center Parcs in Holland.” A door banged shut in Helen’s head; she lived for her daily lane swim, but not if it meant dodging round splashing holidaymakers.

“Of course, there’s the open-air pool in Dortmannhausen village,” Sabine added. “We Germans don’t swim outdoors unless there’s a heatwave, but one of the British wives got a campaign going and persuaded the Kreis authorities to open it from early May, so you won’t have to wait long.”

Now Helen grabbed the tap and let water gush over the crockery, some splashes hitting her. May was still three weeks away. She opened the herbal oil that Louisa had foisted on her at the dinner party and coughed at its biting, acidic scent. She added a few drops to her bowl and watched the pale liquid spread in the running water and mingle with her crockery. It looked like pee. She grabbed the bowl and emptied it.

She watched out of the window as various neighbours set off for school, some on bikes, some walking. She stepped back from the window when Louisa swept past in an enormous four-by-four, powerful enough to cross the Serengeti plains. She slammed the herbal oil bottle into her pedal bin.

By nine the cul-de-sac was deserted. She must have missed Chris next door at number 7 although his sports car was still parked in the street.

She tipped out the rest of her coffee. Now what? Mop the floor? Rearrange the fridge? She could ring Mum. They’d exchanged several texts and she’d sent a postcard from Cologne, but they hadn’t spoken since she left Shrewsbury. If she phoned, Mum would read her mood from a thousand miles away. And she’d say that thing she always said. Like she did when they came back married from Jamaica. Like she did when Helen announced she was giving up her job to join Gary in Germany – “Just as long as you’re happy.” It was the soundtrack through the unauthorized version of her life. When she refused to eat peas; when she chose swimming over ballet; when she changed universities halfway through her degree. She decided to wait a few more days before ringing, do it when she was settled.

A key rack on the wall caught her eye. She picked up the key labelled “Shed”.

***

Inside the concrete construction at the bottom of the garden she discovered a decent set of tools and a lawnmower. She thought of the manicured shrubbery around Louisa’s house and her competitive instinct took hold. But something about being in the back garden unnerved her, and not just the yapping dogs in the nearby kennels. A dark copse of trees grew behind the gardens in Dickensweg, separating them from the gardens of the next street. It joined up at right angles with the wood behind the Howards’ fence. The whole estate enjoyed a similar leafy arrangement. Her skin prickled. An intruder could pass through the network of copses and climb into any garden unnoticed. She gathered her tools and headed to the front of the house.

She stabbed the spade into the flower bed under the kitchen window but only broke off the stalks of a few weeds. She dug harder, but the dense greenery fought her off and she couldn’t reach the soil. Another lunge, and the bones in her arms juddered as the spade hit bedrock. Rubbing the sweat off her forehead, she contemplated how else she could tackle the task.

“Slacking already?” Chris said, coming out of his front door. His voice made her bones rattle more than the bedrock had done.

“Not working today?” she asked. School would be well into the registration period. Didn’t the head of A and D have a form class?

He stepped across their joint path towards her. “Tough job turning your garden into Number Ten.”

She felt him sizing her up. She knew what he saw: damp fringe, ruddy cheeks, traces of snot and grass stain where she’d rubbed her nose.

“A bit of weeding,” she said.

He shook his head. “It’s more than that. You’re a competitive woman.” When she didn’t respond, he continued, “Gary’s told us all about your coaching and your swimming career. You like to be the best, don’t you?”

She lifted the spade again, undecided on whether to sink it into the soil or to bring it down on his head. How dare this stranger pronounce on her life? “I don’t know what you mean.”

“Louisa likes to be the top wife round here, that’s all I’m saying.” He sauntered towards the sports car, gave her a wave and drove off.

She dug faster, scratching and gouging, and turned over a good third of the bed before she heard a car pull up.

“I see Gary’s got you earning your keep.”

In any other tone Helen would have taken the comment as a jokey conversation opener but this voice was as piercing as Chris’s eyes had been.

“Morning, Louisa,” she managed to say. The top wife climbed out of the Serengetiguzzler. Pastel pink tracksuit, spotless trainers, full make-up.

“I stopped to ask whether you wanted to come for a run but I can see you’re busy. How about tomorrow at nine thirty?”

“I’m not much of a runner,” Helen said, blurting out the first thing that came to mind.

“Gary said you ran three miles a day when you lived in England.”

What the hell else had Gary said? “Maybe, once I’ve settled in.”

“Make it soon. It’s bad for the metabolism to stop exercising. You’ll put on weight.”

“I’m sure the gardening will compensate,” Helen said, not snapping.

The door of number 7 opened and Mel backed down the step with a pushchair. She was wearing the same leopard-print leggings that she’d worn at Louisa’s party the previous week.

Glad of the distraction, Helen called out: “I didn’t know you had a baby. Who’s this then?”

The pushchair was empty. Helen assumed the child was still in the house, but Mel’s strained features instinctively told her there was no child.

For once she was glad of Louisa, who said: “Is that another pushchair for HFN? What a knack you have for finding them. Pop it in the boot and I’ll take it up later.”

Mel’s face bulged with colour. “I’ll walk it round. Thanks.”

“If you’re sure you can walk that far,” Louisa said and added for Helen’s benefit, “Mel suffers from shortness of breath.”