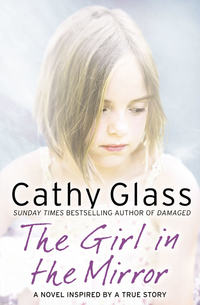

The Girl in the Mirror

She saw the washing machine straight in front of her and next to that the dryer. Crossing the red slate-tiled floor, Mandy pushed the wet pyjama trousers into the washing machine ready for the next wash the following day, then opened the dryer door. There was a single sheet from Grandpa’s bed and two pairs of his pyjama bottoms, still warm from drying – Evelyn must have put them in before going to bed. She gave them a shake and loosely folded them over her arm. She guessed this room was mainly the domain of the housekeeper, Mrs Saunders; her apron hung on the back of the door and the shoes she wore in the house were paired just inside the door. Switching off the light, Mandy came out and returned to the study. If she’d ever been in the laundry room as a child she certainly didn’t remember it.

Grandpa was as she’d left him: on the commode, eyes closed, with John standing behind, holding him. ‘Well done, you found them,’ John said, glancing at the clean laundry draped over her arm. Grandpa didn’t stir and could have been asleep.

Leaving the sheet and spare pair of pyjama trousers on the foot of the bed in case they were needed later, Mandy knelt and concentrated on easing Grandpa’s red and swollen feet into the pyjamas, first one leg then the other. His legs were like dead weights, and there were notches of blue veins clustered on both ankles where the blood had flowed down from sitting. She drew the trousers up to his knees; his pyjama jacket hung over his lap.

‘Ready,’ she said to John, and straightened.

‘On the count of three, Dad,’ John said. ‘One. Two. Three.’ As John lifted, Mandy quickly pulled up the pyjama trousers as she’d seen John previously do, which gave Grandpa as much privacy as possible. ‘Now into bed,’ John said.

Taking most of the weight, John swung Grandpa towards the bed and Mandy guided in his legs. Grandpa moaned but his eyes stayed closed. She pulled up the sheet and tucked it around his neck, as John straightened the pillows. The commode was empty and Mandy moved it to one side, but left the lid off ready for next time. They waited by the bed for Grandpa’s breathing to slowly regulate, signalling he was asleep.

‘Shall I make us a cup of tea?’ Mandy asked, now wide awake.

‘Please. Mine’s skimmed milk with no sugar. And thanks for your help, Mandy. It’s so much easier with two. We make a good team – you and me.’ His gaze lingered appreciatively.

Mandy looked away. A good team. She would have given her right arm to have heard him say that when she’d had her schoolgirl crush. Perhaps it was the embarrassing reminder of that time, or the intimacy of the sick room, but she suddenly felt uncomfortable. ‘I’ll make that tea then,’ she said with a small nod, and left the study.

As she moved around the unfamiliar kitchen, trying to remember where Evelyn had said things were, her thoughts went to her parents. She was pleased her father hadn’t stayed; he would never have coped with seeing Grandpa so vulnerable and compromised, not even able to make it to the commode without wetting himself. Now she was worried her mother wouldn’t be able to cope either when she visited tomorrow. For although her parents hadn’t spoken to John and Evelyn in ten years, they’d always been in close contact with Gran and Grandpa. Indeed her mother saw more of her in-laws than she did her own parents, who lived a long way away. Her mother would be devastated when she saw how ill Grandpa really was and Mandy hoped her father would warn her, although in truth, she thought, nothing could prepare you for the reality of his decline.

She made tea and placed the two mugs on a tray, together with a plate of digestive biscuits, and returned to the study. Grandpa was asleep and John was in his usual armchair with his laptop open before him. He had switched off the main light and the red glow of the lava lamp once more fell across the room, supplemented by the brightness coming from the computer screen. Mandy placed the tray on the coffee table between them, closed the study door and sat in the other armchair, next to John.

‘Thanks, Mandy,’ he said without looking up. ‘You don’t mind if I catch up on a few things?’

‘No, of course not.’

Taking one of the mugs and a couple of biscuits, she sipped the tea and dunked the biscuits as John tapped on the keypad, occasionally extending his arm to reach for his mug. She resisted the temptation to look at the screen, although her eyes were drawn to it. The lava lamp didn’t give off enough light to read a book by and she wanted to stay awake to help if Grandpa woke. Finishing her tea, she checked her phone again. The time showed 11.43. There were no new messages; most of her friends and certainly her father would be in bed now. Returning the mobile to her bag she took out her iPod. Suddenly Grandpa’s legs jerked and he cried out in pain. It was a cry like no other and seemed to rip straight from his body into hers. She was immediately on her feet; so too was John.

‘It’s all right.’ With a hand on each shoulder he began gently massaging, trying to ease away the pain.

Grandpa’s eyes were screwed tightly shut and, despite John’s comforting hands, his face contorted in pain. Then his clenched fists began pummelling the bed either side of him and his legs drummed beneath the sheet. ‘Make it stop. I’m begging you. Please, John!’ he pleaded. ‘I can’t take any more.’

His agony was even worse than it had been that afternoon. Tears sprang to Mandy’s eyes. She felt utterly helpless in the face of his pain. She saw the anguish in John’s face too as he continued rubbing Grandpa’s shoulders, trying to give some relief.

‘Is there nothing we can do?’ she asked in desperation.

‘If it doesn’t pass soon I’ll call the nurse to give him another shot.’

‘Shouldn’t we call him now?’

‘If he gives him a shot now he’ll have to delay the next one. It’s morphine. Too much could kill him.’

Mandy stared in horror as Grandpa’s body arched in pain and John tried impotently to soothe him. It seemed there was nothing they could do to help him and it made her afraid. Guiltily, she thought an overdose of morphine was preferable to this suffering; she would have given it to him herself if it had been possible. Grandpa cried out again. John continued massaging and talking to him in a low, reassuring voice: ‘The pain will pass, Dad. I promise. It will go just as it did last night. Mandy is here with you. Ray has been, and Jean will come tomorrow. We all love you, Dad.’

Tears stung her eyes. Clearly a deep bond had developed between the two men in their nights together, when John had had to deal with Grandpa’s suffering alone and as best he could. Putting aside her own fear she moved closer and, taking one of Grandpa’s hands between hers, began rubbing it. Suddenly his back arched again and, just as Mandy was sure he couldn’t take any more, the pain seemed to peak and subside. His body went limp, collapsing flat on the bed. He was so still and quiet that for a moment she thought he was dead.

‘Thank God,’ John said quietly, taking his hands from Grandpa’s shoulders. ‘He should sleep now.’ Only then did she hear Grandpa take one long deep breath and saw his chest rise and fall.

Mandy remained where she was at the side of the bed, frozen in the horror of what she’d seen. Her heart raced and she felt icy cold. Never before had she witnessed someone in such torment. Grandpa shouldn’t have to suffer; he was a good, kind man, proud and caring, who’d always done the best for his family. He shouldn’t have to end his life begging for release; he should leave it as he lived it – with dignity and self-respect.

She felt the tears escape and run down her cheeks. She turned away from the bed so John couldn’t see. Her gaze fell on the lamp as a red bubble of oil stretched to its limit and the top broke away. She heard John’s voice behind her, tender and close. ‘Are you all right, Mandy?’

Then she felt his hands lightly on her shoulders. Then he was turning her around to face him. Without meeting his eyes and grateful for his support she rested her head against his chest and cried openly. His arms closed around her, safe and secure; he held her tight and comforted her just as he had when she’d been a child.

Ten

It was as though John had to reaffirm his loyalty to Evelyn, Mandy thought later, when he told her yet again how very supportive Evelyn had been. Supportive when the recession had bitten and his business had suffered, and when he’d made an error of judgement in his private life some years before – although exactly what he didn’t state. Evelyn had always been there for him, John said, his rock, and now he was pleased to have the chance to help her by shouldering some of the responsibility for looking after Grandpa.

It was just before dawn. Through the parting in the curtains of the study Mandy could see the distant edge of skyline beginning to lighten. John and she had been talking and dozing intermittently all night in the peculiar intimacy of the sick room with its red bubbles of moving light. Grandpa had woken every couple of hours in discomfort and in need of reassurance, but the pain hadn’t been as bad as that first time, when Mandy had cried and John had comforted her. When she’d stopped crying and had thanked John, he’d seemed embarrassed and had apologized. Since then he’d been extolling Evelyn’s virtues at every opportunity as though he felt guilty. Why he should feel guilty for comforting her, Mandy didn’t know.

At 6.30 a.m. she thought she’d take a shower while all was quiet. John was again dozing in the chair and Grandpa, more peaceful than he’d been all night, seemed in a deep sleep. Mandy stole quietly from the study and upstairs to the bedroom Evelyn had previously shown her. Taking the fresh underwear her aunt had placed on the bed, she went into the guest bathroom and locked the door. Selecting body-wash and shampoo from the array of small bottles on the glass shelf, she showered and washed her hair. Half an hour later, dressed and feeling more refreshed, she returned to the study. As she entered she was surprised to see Evelyn sitting where John had been, also dressed, lipstick on and apparently ready to face the new day.

‘Morning.’ Evelyn smiled brightly.

‘Morning,’ Mandy said, going over and kissing her aunt’s cheek.

The curtains were now fully open and the early-morning sun filtered through the lattice window of the study. The room seemed more optimistic now the natural light had replaced the red glow of the lamp.

‘Shall I fetch you a hairdryer?’ Evelyn asked.

‘No, thanks. I let it dry naturally. Where’s John?’

‘Taking a nap upstairs. He might have to go to the office later. I understand you had a pretty rough night.’

Mandy nodded. ‘But John is so good with Grandpa.’

‘Yes, I don’t know what I’d do without him.’ Evelyn stood up. ‘I usually make coffee now, before Mrs Saunders arrives at eight to make breakfast. Would you like one?’

‘Love one. Thanks.’

A routine then fell into place which Mandy guessed had developed during the past week since Grandpa had come to stay, and would probably continue for as long as it was needed. Evelyn returned to the study a quarter of an hour later with Mandy’s coffee but didn’t stay. ‘I drink mine on the hoof,’ she said, ’while I see to a few things in the kitchen.’ At just gone 8 a.m. Mrs Saunders knocked on the door and came in carrying a fresh jug of water. She said good morning, swapped the fresh jug of water for the one on the tray and, collecting Mandy’s empty coffee cup, asked if she needed anything, which she didn’t. At 8.45 Gran came slowly into the study on her walking frame, having being helped downstairs by Evelyn, who then disappeared. Mandy kissed Gran good morning and they sat by the bed until 9 a.m. when Mrs Saunders reappeared and announced that breakfast was ready.

‘We have breakfast in the morning room while Evelyn sits with Will,’ Gran explained to Mandy. On cue Evelyn came in and said she would sit with Grandpa while they ate breakfast. Gran flashed Mandy a knowing smile.

Mandy helped Gran to her feet and walked by her side along the rear hall to the morning room. As she entered the room she felt she was on a film set for Brideshead Revisited or a similar period piece. Mrs Saunders was standing by the oak sideboard where five silver tureens had been arranged with matching silver serving spoons. The circular oak table was now formally laid for two, with silver cutlery, Aynsley rose-patterned china cups and saucers, and a ringed linen napkin beside each place setting. ‘If you’d like to help yourself…’ Mrs Saunders said to Mandy, removing the lids from the tureens. ‘There’s scrambled eggs, bacon, sausage, mushrooms, grilled tomatoes, and toast in the rack.’

Mandy wondered if they always breakfasted like this, and what Grandpa, with his simple tastes and dislike of pretension, would have made of it. Not a lot, she thought. But she was hungry.

‘Thank you,’ she said, accepting the breakfast plate Mrs Saunders handed to her. She then went along the sideboard and took a spoonful from each of the tureens while the housekeeper served Gran. Coming to the end she took a glass of orange juice from the tray and then sat at the table opposite Gran. But unlike the day before, when she’d found the formal meals served in the dining room quite bizarre and somewhat distasteful given what was happening to Grandpa, she now found the ritual almost reassuring. Despite the turmoil and anxiety of the family crisis, here was something that could be relied upon: dependable, consistent, and a complete distraction. It was presumably why Evelyn continued with the routine of formal meals.

Shortly before 9.30 the doorbell rang. ‘That’ll be the nurse,’ Gran said. ‘Evelyn or John will see to him.’

‘I think John’s asleep,’ Mandy said.

‘Then Evelyn will see to him. Evelyn likes me to stay here until the nurse has finished. I usually do as I’m told.’

Mandy returned Gran’s smile and they continued eating. They heard Mrs Saunders answer the front door and then Evelyn’s voice greet the nurse in the hall. When they’d finished eating Mrs Saunders cleared away the plates and they remained at the table until Evelyn had seen the nurse out and came into the morning room and said Grandpa had had his wash and injection.

Evelyn helped Gran onto her walking frame and Mandy followed them to the study. As she entered she saw the commode had gone and a capped polythene bottle was now beside the bed. Gran noticed it too.

‘He won’t use that,’ Gran said indignantly.

‘We’ll give it a try, Mum. It should stop the accidents and make it easier for Dad.’

‘And his pain relief?’ Gran asked. ‘You were going to see if it could be increased.’

‘It’s all taken care of. Don’t you worry, Mum.’ Mandy thought Evelyn sounded patronizing but Gran either didn’t hear it or chose to ignore it. She nodded and returned to her chair by the bed.

‘Why don’t you have a lie-down?’ Evelyn suggested to Mandy. ‘Grandpa should sleep for most of the morning now, and I’ll be popping in and out.’

‘If I’m not needed I might go for a short walk,’ Mandy said. ‘Get a breath of fresh air.’

‘Of course, love. Do whatever you please.’ Evelyn smiled. ‘We’re all very grateful you stayed.’

‘I’m pleased I stayed, really I am,’ Mandy said. ‘I think I might walk into the village. Do you want anything from the shop if I get that far?’

Mandy saw the smile on Evelyn’s face vanish. There was a short pause before she replied, tightly: ‘No, no thank you. I don’t use that store any more.’ Throwing Gran a pointed glance she said something about having to see Mrs Saunders and left the room.

Mandy looked at Gran for explanation but Gran had returned her attention to Grandpa. ‘See you later then,’ Mandy said. ‘Do you want anything from the store?’

‘No thanks, love, but you can give my regards to Mrs Pryce. She works there.’

‘Will do.’ Picking up her bag from beside the chair Mandy threw it over her shoulder and, kissing Gran and Grandpa goodbye, left the study.

Pryce? Mrs Pryce? The name sounded familiar, Mandy thought as she went to the cloakroom before setting off. Why it should sound familiar she didn’t know, nor why Evelyn had behaved oddly when she’d mentioned the village store. But one thing she did know was that there were no toilets on the walk into the village, and if you got caught short you had to go behind a hedge. She remembered that Sarah and she had had to take turns to squat out of sight of the road, while the other looked out for passing cars or, worse, someone walking their dog along the path.

Tucking her mobile into her jacket pocket – Adam had texted earlier saying he would phone mid-morning – and with her bag slung over her shoulder, Mandy let herself out of the front door. It was a lovely fresh spring morning, like yesterday – which had been Tuesday, she had to remind herself. Too much food, too little sleep and being closeted in the hot study were making her brain sluggish, but her body restless. A brisk walk was exactly what she needed, she thought, to ‘blow away the cobwebs’ as Gran would say.

Mandy followed the path around the edge of the drive and turned right on to the narrow tarmac footpath which ran beside the single-track lane. It was the road her father had driven along yesterday, the only road leading to and from the house and which led to the main road and then into the village. Mandy walked quickly, invigorated from being outside in the fresh air, and also from the luxury of being alone. She wasn’t used to having company and making conversation for large parts of the day. Since she’d given up work she’d had solitude each day during the working week to concentrate on her painting. She’d only seen Adam in the evenings. In this at least I’ve been disciplined, she thought cynically, although she had to admit her time alone had produced very little: a few half-baked ideas, the odd sketch, but no painting. If I could just finish one painting, she thought, I’m sure it would restore my confidence and make a difference – to everything.

She passed the driveway which led to her aunt’s closest neighbour, although the bungalow, standing in its own substantial grounds, was so far away from Evelyn’s house it hardly constituted a ‘neighbour’. Indeed, all the properties she passed had their own land and were very secluded; ‘exclusive’ was the word an estate agent would have used, she thought. And although the houses were slightly familiar from when she’d passed them in the car the day before, she had no other memory of the road despite Sarah and her often walking into the village.

Mandy felt her phone vibrate in her pocket and quickly took it out.

‘Miss you,’ Adam said, as soon as she answered. ‘When are you coming home?’

‘Miss you too,’ she said, appreciating the sound of his voice. ‘Adam, I’ve said I’d stay and help. My aunt and uncle are exhausted.’ And grateful for the chance to off-load she told him of the dreadful pain Grandpa had been in between the shots of morphine, and the night she’d spent in the study-cum-sick room. She felt herself choking up as she described how John and she had tried to soothe away the pain. ‘He’s very poorly,’ she finished, not wanting to cry on the phone. She was about to tell him of the strange thoughts and flashbacks she’d been having since arriving at her aunt’s, but she realized how ridiculous it would sound and instead told him of the breakfast laid on the sideboard in silver tureens. Her phone began to bleep, signalling the battery was about to run out. ‘Sod it!’ she said, annoyed. ’I’ll have to phone you back later from the house.’ Quickly winding up and swapping ‘Miss you’s, she said goodbye. Before the battery went completely she texted her father, asking him to bring her phone charger, which she’d left plugged in beside her bed. Unaware she wouldn’t be returning home that evening, she hadn’t brought it with her. She now wondered how many other things she’d forgotten to ask her father to collect from her bedsit and which she would find she needed. Epilator, she thought. Never mind, I’ll buy a razor from the village shop.

The narrow tarmac path Mandy now trod looked like many other country paths and was no more familiar. But the brilliant green of the early spring shoots, the brown earth, blue sky and picture-postcard rural tranquillity suddenly caught her artistic eye. She knew she should try and remember it, as she used to, to paint later. Whenever she’d been out, if she came across a scene that appealed she used to be able to capture it in her mind’s eye – freeze-frame it – and then transfer it to canvas when she got home. But in the last seven months, since she’d been unable to paint, the magic of the scene always faded and lost its intensity, so that all she managed were some drawings in her sketch pad. Perhaps this will be different, she thought. Try to be positive. She looked around at the beauty of the countryside and willed herself to remember what she saw.

A house appeared through the trees to her left and then the path broke for a concealed and overgrown driveway. Mandy was about to cross the drive and then jumped back as a car suddenly appeared. As it drew level the driver nodded and she felt a sudden surge of familiarity. Hadn’t a car pulled out of one of these driveways when Sarah and she had been about to cross on one of their walks into the village? She thought it had. A Land-Rover with two large cream dogs in the back? She was sure now, for she remembered they’d been so busy chatting they hadn’t seen the Land-Rover until the last second, and had had to jump back on to the path to avoid being knocked down. Perhaps it was the shock of it nearly happening again that had triggered this memory, like the shock of suddenly bumping into John when she’d first arrived had reminded her of her schoolgirl crush. She wondered if the man in the muddy Land-Rover who’d told them off for not looking where they were going still lived in the house along here. But which one? She had no idea. She also wondered why her recollections were so piecemeal and random, and why she had no control over them. It was not only strange but disturbing. Better not to dwell on it. She concentrated on the path ahead and checked the driveways for cars.

Coming to a halt at the end of the lane Mandy waited to cross the road. Whereas she’d only seen a couple of cars on the lane, now the cars sped by at regular intervals in intermittent rushes of air that fanned her face and blew back her hair. She spotted a gap in the traffic and crossed the road, then began towards the village. She passed a speed camera box and further up a banner announcing ‘Bypass Now’. To her right stood the early-nineteenth-century stone church with half a dozen headstones in a small, neatly tended graveyard at the front. A massive oak tree rose on the other side of the church, its branches overhanging the pavement. Beside the church was a duck pond and next to that the village pub with its original signboard of a painting of a red lion suspended from the post outside. The road gently curved away and then rose up and out of the village, finally meeting the blue horizon in the distance. Mandy focused on the village scene ahead, so unlike London, but which did seem vaguely familiar. She made her way along the narrow pavement, keeping close to the cottage walls and well away from the traffic that flashed by.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов