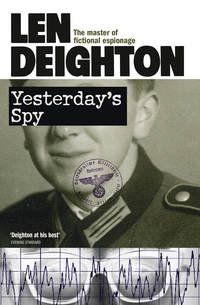

Yesterday’s Spy

Even by Dawlish’s standards that was an understatement. It was a large gloomy apartment. The wallpaper and paintwork were in good condition and so was the cheap carpeting, but there were no pictures, no books, no ornaments, no personal touches. ‘A machine for living in,’ said Dawlish.

‘Le Corbusier at his purest,’ I said, anxious to show that I could recognize a cultural quote when I heard one.

It was like the barrack-room I’d had as a sergeant, waiting for Intelligence training. Iron bed, a tiny locker, plain black curtains at the window. On the windowsill there were some withered crumbs. I suppose no pigeon fancied them when just a short flight away the tourists would be throwing them croissants, and they could sit down and eat with a view of St James’s Park.

There was a school yard visible from the window. The rain had stopped and the sun was shining. Swarms of children made random patterns as they sang, swung, jumped in puddles and punched each other with the same motiveless exuberance that, organized, becomes war. I closed the window and the shouting died. There were dark clouds; it would rain again.

‘Worth a search?’ said Dawlish.

I nodded. ‘There will be a gun. Sealed under wet plaster perhaps. He’s not the kind of man to use the cistern or the chimney: either tear it to pieces or forget it.’

‘It’s difficult, isn’t it,’ said Dawlish. ‘Don’t want to tear it to pieces just to find a gun. I’m interested in documents – stuff that he needs constant access to.’

‘There will be nothing like that here,’ I said.

Dawlish walked into the second bedroom. ‘No linen on the bed, you notice. No pillows, even.’

I opened the chest of drawers. There was plenty of linen there; all brand new, and still in its wrappings.

‘Good quality stuff,’ said Dawlish.

‘Yes, sir,’ I said.

Dawlish opened the kitchen cupboards and recited their contents. ‘Dozen tins of meat, dozen tins of peas, dozen bottles of beer, dozen tins of rice pudding. A package of candles, unused, a dozen boxes of matches.’ He closed the cupboard door and opened a kitchen drawer. We stared at the cutlery for a moment. It was all new and unused. He closed it again without comment.

‘No caretaker,’ I said. ‘No landlady, no doorman.’

‘Precisely,’ said Dawlish. ‘And I’ll wager that the rent is paid every quarter day, without fail, by some solicitor who has never come face to face with his client. No papers, eh?’

‘Cheap writing-pad and envelopes, a book of stamps, postcards with several different views of London – might be a code device – no, no papers in that sense.’

‘I look forward to meeting your friend Champion,’ said Dawlish. ‘A dozen tins of meat but three dozen bars of soap – that’s something for Freud, eh?’

I let the ‘your friend’ go unremarked. ‘Indeed it is, sir,’ I said.

‘None of it surprises you, of course,’ Dawlish said, with more than a trace of sarcasm.

‘Paranoia,’ I said. ‘It’s the occupational hazard of men who’ve worked the sort of territories that Champion has worked.’ Dawlish stared at me. I said, ‘Like anthrax for tannery workers, and silicosis for miners. You need somewhere … a place to go and hide for ever …’ I indicated the store cupboard, ‘… and you never shake it off.’

Dawlish walked through into the big bedroom. Blantyre and his sidekick made themselves scarce. Dawlish opened the drawers of the chest, starting from the bottom like a burglar so that he didn’t have to bother closing them. There were shirts in their original Cellophane bags, a couple of knitted ties, sweaters and plain black socks. Dawlish said, ‘So should I infer that you have a little bolt-hole like this, just in case the balloon goes up?’ Even after all these years together, Dawlish had to make sure his little jokes left a whiff of cordite.

‘No, sir,’ I said. ‘But on the new salary scale I might be able to afford one – not in central London, though.’

Dawlish grunted, and opened the wardrobe. There were two dark suits, a tweed jacket, a blazer and three pairs of trousers. He twisted the blazer to see the inside pocket. There was no label there. He let it go and then took the tweed jacket off its hanger. He threw it on the bed.

‘What about that?’ said Dawlish.

I said, ‘High notch, slightly waisted, centre-vented, three-button jacket in a sixteen-ounce Cheviot. Austin Reed, Hector Powe, or one of those expensive mass-production tailors. Not made to measure – off the peg. Scarcely worn, two or three years old, perhaps.’

‘Have a look at it,’ said Dawlish testily.

‘Really have a look?’

‘You’re better at that sort of thing than I am.’ It was Dawlish’s genius never to tackle anything he couldn’t handle and always to have near by a slave who could.

Dawlish took out the sharp little ivory-handled penknife that he used to ream his pipe. He opened it and gave it to me, handle first. I spread the jacket on the bed and used the penknife to cut the stitches of the lining. There were no labels anywhere. Even the interior manufacturer’s codes had been removed. So I continued working my way along the buckram until I could reach under that too. There was still nothing.

‘Shoulder-pads?’ I said.

‘Might as well,’ said Dawlish. He watched me closely.

‘Nothing,’ I said finally. ‘Would you care to try the trousers, sir?’

‘Do the other jackets.’

I smiled. It wasn’t that Dawlish was obsessional. It was simply his policy to run his life as though he was already answering the Minister’s questions. You searched all the clothing? Yes, all the clothing. Not, no, just one jacket, selected at random.

I did the other jackets. Dawlish proved right. He always proves right. It was in the right-hand shoulder-pad of one of the dark suits that we found the paper money. There were fourteen bills: US dollars, Deutsche Marks and sterling – a total of about twelve thousand dollars at the exchange rate then current.

But it was in the other shoulder-pad that we found the sort of document Dawlish was looking for. It was a letter signed by the Minister Plenipotentiary of the United Arab Republic’s Embassy in London. It claimed that Stephen Champion had diplomatic status as a naturalized citizen of the United Arab Republic and listed member of the Diplomatic Corps.

Dawlish read it carefully and passed it across to me. ‘What do you think about that?’ he asked.

To tell you the truth, I thought Dawlish was asking me to confirm that it was a forgery, but you can never take anything for granted when dealing with Dawlish. I dealt him his cards off the top of the deck. ‘Champion is not on the London Diplomatic List,’ I said, ‘but that’s about the only thing I’m certain of.’

Dawlish looked at me and sniffed. ‘Can’t even be certain of that,’ he said. ‘All those Abduls and Ahmeds and Alis … suppose you were told that one of those was the name Champion had adopted when converted to the Muslim faith. What then … ?’

‘It would keep the lawyers arguing for months,’ I said.

‘And what about the Special Branch superintendent at London airport, holding up the aeroplane departing to Cairo? Would he hold a man who was using this as a travel document, and risk the sort of hullabaloo that might result if he put a diplomat in the bag?’

‘No,’ I said.

‘Precisely,’ said Dawlish.

A gust of wind rattled the window panes and the sky grew dark. He said nothing more. I took my coat off and hung it up. It was no good pretending that I wouldn’t be here all day. There’s only one way to tackle those jobs: you do it stone by stone, and you do it yourself. Dawlish sent Blantyre and his associate away. Then he went down to the car and called the office. I began to get some idea of the priorities when he told me he’d cancelled everything for the rest of the day. He sat down on the kitchen chair and watched me work.

There was nothing conclusive, of course: no dismembered limbs or bloodstains, but clothes that I’d seen Melodie Page wearing were packed in plastic carrier-bags, sandwiched neatly between two sheets of plasterboard, sealed at every edge, and integrated beautifully into the kitchen ceiling.

The wallpaper near the bed had deep scratches, and a broken fragment of fingernail remained embedded there. There was the faintest smell of carbolic acid from the waste-trap under the sink, and from there I managed to get a curved piece of clear glass that was one part of a hypodermic syringe. Other than that, there was only evidence of removal of evidence.

‘It’s enough,’ said Dawlish.

From the school yard across the street came all the exuberant screams that the kids had been bottling up in class. It was pouring with rain now, but children don’t mind the rain.

5

Schlegel likes Southern California. Sometimes I think it’s the only thing he does like. You take Southern California by the inland corners, he says, jerk it, so that all the shrubbery and real-estate falls into a heap along the coast, and you know what you’ve got? And I say, yes, you’ve got the French Riviera, because I’ve heard him say it before.

Well, on Monday I’d got the French Riviera. Or, more precisely, I’d got Nice. I arrived in my usual neurotic way: ten hours before schedule, breaking my journey in Lyon and choosing the third cab in the line-up.

It was so easy to remember what Nice had looked like the first time I saw it. There had been a pier that stretched out to sea, and barbed wire along the promenade. Armed sentries had stood outside the sea-front hotels, and refugees from the north stood in line for work, or begged furtively outside the crowded cafés and restaurants. Inside, smiling Germans in ill-fitting civilian suits bought each other magnums of champagne and paid in mint-fresh military notes. And everywhere there was this smell of burning, as if everyone in the land had something in their possession that the Fascists would think incriminating.

Everyone’s fear is different. And because bravery is just the knack of suppressing signs of your own fear, bravery is different too. The trouble with being only nineteen is that you are frightened of all the wrong things; and brave about the wrong things. Champion had gone to Lyon. I was all alone, and of course then too stupid not to be thankful for it. No matter what the movies tell you, there was no resistance movement visible to the naked eye. Only Jews could be trusted not to turn you over to the Fascists. Men like Serge Frankel. He’d been the first person I’d contacted then, and he was the first one I went to now.

It was a sunny day, but the apartment building, which overlooked the vegetable market, was cold and dark. I went up the five flights of stone stairs. Only a glimmer of daylight penetrated the dirty windows on each landing. The brass plate at his door – ‘Philatelic Expert’ – was by now polished a little smoother, and there was a card tucked behind the bell that in three languages said ‘Buying and Selling by Appointment Only’.

The same heavy door that protected his stamps, and had given us perhaps groundless confidence in the old days, was still in place, and the peep-hole through which he’d met the eyes of the Gestapo now was used to survey me.

‘My boy! How wonderful to see you.’

‘Hello, Serge.’

‘And a chance to practise my English,’ he said. He reached forward with a white bony hand, and gripped me firmly enough for me to feel the two gold rings that he wore.

It was easy to imagine Serge Frankel as a youth: a frail-looking small-boned teenager with frizzy hair and a large forehead and the same style of gold-rimmed spectacles as he was wearing now.

We went into the study. It was a high-ceilinged room lined with books, their titles in a dozen or more languages. Not only stamp catalogues and reference books, but philosophy from Cicero to Ortega y Gasset.

He sat in the same button-back leather chair now as he had then. Smiling the same inscrutable and humourless smile, and brushing at the ash that spilled down the same sort of waistcoat, leaving there a grey smear like a mark of penitence. It was inevitable that we should talk of old times.

Serge Frankel was a Communist – student of Marx, devotee of Lenin and servant of Stalin. Born in Berlin, he’d been hunted from end to end of Hitler’s Third Reich, and had not seen his wife and children since the day he waved goodbye to them at Cologne railway station, wearing a new moustache and carrying papers that described him as an undertaker from Stettin.

During the Civil War in Spain, Frankel had been a political commissar with the International Brigade. During the tank assault on the Prado, Frankel had destroyed an Italian tank single-handed, using a wine bottle hastily filled with petrol.

‘Tea?’ said Frankel. I remembered him making tea then as he made it now: pouring boiling water from a dented electric kettle into an antique teapot with a chipped lid. Even this room was enigmatic. Was he a pauper, hoarding the cash value of the skeleton clock and the tiny Corot etching, or a Croesus, indifferent to his plastic teaspoons and museum postcards of Rouault?

‘And what can I do for you, young man?’ He rubbed his hands together, exactly as he had done the day I first visited him. Then, my briefing could hardly have been more simple: find Communists and give them money, they had told me. But most of life’s impossible tasks – from alchemy to squaring the circle – are similarly concise. At that time the British had virtually no networks in Western Europe. A kidnapping on the German–Dutch border in November 1939 had put both the European chief of SIS and his deputy into the hands of the Abwehr. A suitcase full of contact addresses captured in The Hague in May 1940, and the fall of France, had given the coup de grâce to the remainder. Champion and I were ‘blind’, as jargon has it, and halt and lame, too, if the truth be told. We had no contacts except Serge Frankel, who’d done the office a couple of favours in 1938 and 1939 and had never been contacted since.

‘Communists.’ I remembered the way that Frankel had said it, ‘Communists’, as though he’d not heard the word before. I had been posing as an American reporter, for America was still a neutral country. He looked again at the papers I had laid out on his writing table. There was a forged US passport sent hurriedly from the office in Berne, an accreditation to the New York Herald Tribune and a membership card of The American Rally for a Free Press, which the British Embassy in Washington recommended as the reddest of American organizations. Frankel had jabbed his finger on that card and pushed it to the end of the row, like a man playing patience. ‘Now that the Germans have an Abwehr office here, Communists are lying low, my friend.’ He had poured tea for us.

‘But Hitler and Stalin have signed the peace pact. In Lyon the Communists are even publishing a news-sheet.’

Frankel looked up at me, trying to see if I was being provocative. He said, ‘Some of them are even wearing the hammer and sickle again. Some are drinking with the German soldiers and calling them fellow workers, like the Party tells them to do. Some have resigned from the Party in disgust. Some have already faced firing squads. Some are reserving their opinion, waiting to see if the war is really finished. But which are which? Which are which?’ He sipped his tea and then said, ‘Will the English go on fighting?’

‘I know nothing about the English, I’m an American,’ I insisted. ‘My office wants a story about the French Communists and how they are reacting to the Germans.’

Frankel moved the US passport to the end of the row. It was as if he was tacitly dismissing my credentials, and my explanations, one by one. ‘The people you want to see are the ones still undecided.’

He looked up to see my reaction.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘The ones who have not signed a friendship treaty with the Boche, eh?’

I nodded.

‘We’ll meet again on Monday. What about the café in the arcade, at the Place Massena. Three in the afternoon.’

‘Thank you, Mr Frankel. Perhaps there’s something I can do for you in return. My office have let me have some real coffee …’

‘Let’s see what happens,’ said Frankel. But he took the tiny packet of coffee. Already it was becoming scarce.

I picked up the documents and put them into my pocket. Frankel watched me very closely. Making a mistake about me could send him to a concentration camp. We both knew that. If he had any doubts he’d do nothing at all. I buttoned up my coat and bowed him goodbye. He didn’t speak again until I reached the door. ‘If I am wearing a scarf or have my coat buttoned at the collar, do not approach me.’

‘Thank you, Mr Frankel,’ I said. ‘I’ll watch out for that.’

He smiled. ‘It seems like only yesterday,’ he said. He poured the tea. ‘You were too young to be a correspondent for an American newspaper, but I knew you were not working for the Germans.’

‘How did you know that?’

He passed the cup of tea to me, murmuring apologies about having neither milk nor lemon. He said, ‘They would have sent someone more suitable. The Germans had many men who’d lived in America long enough. They could have chosen someone in his thirties or forties with an authentic accent.’

‘But you went ahead,’ I reminded him.

‘I talked to Marius. We guessed you’d be bringing money. The first contact would have to bring money. We could do nothing without cash.’

‘You could have asked for it, or stolen it.’

‘All that came later – the bank hold-ups, the extortion, the loans. When you arrived we were very poor. We were offering only a franc for a rifle and we could only afford to buy the perfect Lebel pattern ones even then.’

‘Rifles the soldiers had thrown away?’ It was always the same conversation that we had, but I didn’t mind.

‘The ditches were full of them. It was that that started young Marius off – the bataillon Guernica was his choice of name – I thought it would have been better to have chosen a victory to celebrate, but young Marius liked the unequivocally anti-German connotation that the Guernica bombing gave us.’

‘But on the Monday you said no,’ I reminded him.

‘On the Monday I told you not to have high hopes,’ he corrected me. He ran his long bony fingers back into his fine white wispy hair.

‘I knew no one else, Serge.’

‘I felt sorry for you when you walked off towards the bus station, but young Marius wanted to look at you and make up his own mind. And that way it was safer for me, too. He decided to stop you in the street if you looked genuine.’

‘At the Casino tabac he stopped me. I wanted English cigarettes.’

‘Was that good security?’

‘I had the American passport. There was no point in trying to pretend I was French.’

‘And Marius said he might get some?’

‘He waited outside the tabac. We talked. He said he’d hide me in the church. And when Champion returned, he hid us both. It was a terrible risk to take for total strangers.’

‘Marius was like that,’ said Frankel.

‘Without you and Marius we might never have got started,’ I said.

‘Hardly,’ said Frankel. ‘You would have found others.’ But he smiled and was flattered to think of himself as the beginning of the whole network. ‘Sometimes I believe that Marius would have become important, had he lived.’

I nodded. They’d made a formidable partnership – the Jewish Communist and the anti-Fascist priest – and yet I remembered Frankel hearing the news of Marius’s death without showing a flicker of emotion. But Frankel had been younger then, and keen to show us what his time in Moscow had really taught him.

‘We made a lot of concessions to each other – me and Marius,’ Frankel said. ‘If he’d lived we might have achieved a great deal.’

‘Sure you would,’ I said. ‘He would be running the Mafia, and you would have been made Pope.’

Flippancy was not in the Moscow curriculum, and Frankel didn’t like it. ‘Have you seen Pina Baroni yet?’

‘Not yet,’ I said.

‘I see her in the market here sometimes,’ said Frankel. ‘Her little boutique in the Rue de la Buffa is a flourishing concern, I’m told. She’s over the other business by now, and I’m glad …’

The ‘other business’ was a hand-grenade thrown into a café in Algiers in 1961. It killed her soldier husband and both her children. Pina escaped without a scratch, unless you looked inside her head. ‘Poor Pina,’ I said.

‘And Ercole …’ Frankel continued, as if he didn’t want to talk of Pina, ‘… his restaurant prospers – they say his grandson will inherit; and “the Princess” still dyes her hair red and gets raided by the social division.’

I nodded. The ‘social division’ was the delicate French term for vice squad.

‘And Claude l’avocat?’

‘It’s Champion you want to know about,’ said Frankel.

‘Then tell me about Champion.’

He smiled. ‘We were all taken in by him, weren’t we? And yet when you look back, he’s the same now as he was then. A charming sponger who could twist any woman round his little finger.’

‘Yes?’ I said doubtfully.

‘Old Tix’s widow, she could have sold out for a big lump sum, but Champion persuaded her to accept instalments. So Champion is living out there in the Tix mansion, with servants to wait on him hand and foot, while Madame Tix is in three rooms with an outdoor toilet, and inflation has devoured what little she does get.’

‘Is that so?’

‘And now that he sees the Arabs getting rich on the payments for oil, Champion is licking the boots of new masters. His domestic staff are all Arabs, they serve Arab food out there at the house, they talk Arabic all the time and when he visits anywhere in North Africa he gets VIP treatment.’

I nodded. ‘I saw him in London,’ I said. ‘He was wearing a fez and standing in line to see “A Night in Casablanca”.’

‘It’s not funny,’ said Frankel irritably.

‘It’s the one where Groucho is mistaken for the Nazi spy,’ I said, ‘but there’s not much singing.’

Frankel clattered the teapot and the cups as he stacked them on the tray. ‘Our Mister Champion is very proud of himself,’ he said.

‘And pride comes before a fall,’ I said. ‘Is that what you mean, Serge?’

‘You said that!’ said Frankel. ‘Just don’t put words into my mouth, it’s something you’re too damned fond of doing, my friend.’

I’d touched a nerve.

Serge Frankel lived in an old building at the far end of the vegetable market. When I left his apartment that Monday afternoon, I walked up through the old part of Nice. There was brilliant sunshine and the narrow alleys were crowded with Algerians. I picked my way between strings of shoes, chickens, dates and figs. There was a peppery aroma of merguez sausages frying, and tiny bars where light-skinned workers drank pastis and talked football, and dark-skinned men listened to Arab melodies and talked politics.

From the Place Rosetti came the tolling of a church bell. Its sound echoed through the alleys, and stony-faced men in black suits hurried towards the funeral. Now and again, kids on mopeds came roaring through the alleys, making the shoppers leap into doorways. Sometimes there came cars, inch by inch, the drivers eyeing the scarred walls where so many bright-coloured vehicles had left samples of their paint. I reached the boulevard Jean Jaurès, which used to be the moat of the fortified medieval town, and is now fast becoming the world’s largest car park. There I turned, to continue along the alleys that form the perimeter of the old town. Behind me a white BMW was threading through the piles of oranges and stalls of charcuterie with only a fraction to spare. Twice the driver hooted, and on the third time I turned to glare.

‘Claude!’ I said.

‘Charles!’ said the driver. ‘I knew it was you.’

Claude had become quite bald. His face had reddened, perhaps from the weather, the wine or blood pressure. Or perhaps all three. But there was no mistaking the man. He still had the same infectious grin and the same piercing blue eyes. He wound the window down. ‘How are you? How long have you been in Nice? It’s early for a holiday, isn’t it?’ He drove on slowly. At the corner it was wide enough for him to open the passenger door. I got into the car alongside him. ‘The legal business looks like it’s flourishing,’ I said. I was fishing, for I had no way of knowing if the cheerful law student whom we called Claude l’avocat was still connected with the legal profession.