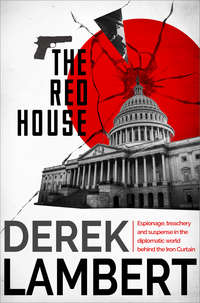

The Red House

The ambassador wondered whether to confide in Zhukov. Such a confidence might be interpreted as weakness in himself; perhaps even Zhukov himself was a senior member of the K.G.B.—second secretary at forty-four did not seem to be much of an achievement for such an intelligent man. You could never tell; nor could you equate seniority in the K.G.B. with diplomatic seniority. Although Valentin Zuvorin was fairly sure of his authority.

To hell with such furtive considerations: he, Valentin Zuvorin, occupied the most important post in the Soviet overseas diplomatic service. He sat down again near the piano. ‘Tardovsky,’ he said, ‘was on the point of persuading a neurotic American from the State Department to hand over secret documents about American intent in Vietnam and the Middle East. The Americans thought Tardovsky might defect—he had no such intention, of course. Anyway the C.I.A. and F.B.I. got wind of it. There was a squalid scene in a bar on 14th Street’—no need to elaborate—‘with the result that Tardovsky has lost all credibility and therefore all usefulness to us in Washington either as an agent or a diplomat. So he has been recalled through no fault of his own.’ Although, Zuvorin thought, his future has not been enhanced.

‘I see.’ Zhukov pondered the fortuitous factors of success.

‘Is that all you have to say, comrade?’

‘I am deeply honoured, of course. But …’

‘But what?’

‘Does this mean that I will have to carry out similar subversive duties?’

Zuvorin almost patted him on the head. ‘Don’t worry yourself about such matters. It is sufficient that you have been chosen to fill an important diplomatic post. That is all that matters for the moment.’

For who am I, the ambassador asked himself, to say whether or not you are to become a spy?

Zhukov found that his new office duties were really an extension of his old ones. Only now the emphasis was more political. He still translated American newspapers, magazines, government reports, but his reading was more selective and he was expected to be more interpretive—hooking nuances of meaning lost in flat translation. He was also asked to translate government directives that somehow reached the Embassy before publication, and some that were never published at all. These were given to him by Mikhail Brodsky, and Zhukov only typed two copies of his translation, one for the ambassador, one for Brodsky. More deference from the rest of the staff, an office of his own, the satisfaction of responsibility: these were the perquisites of the new job, and they were balanced by the demands for industry and punctuality of Ambassador Zuvorin who answered similar demands from Moscow.

Most of the day Zhukov sat at his desk in his high-ceilinged Pullman office where perhaps once a nanny had put the children of rich parents to bed. He drank gallons of tea made with lemon and Narzan mineral water imported from Russia. At night he took his work home and slept with dreams dominated by United States policies, and sometimes in his waking moments wondered what other duties might lie ahead.

One Saturday shortly after his promotion Vladimir Zhukov, on the advice of several well-wishers from within the Embassy, took Valentina for a drive into the ghetto. Time, they said, to see the other side of the coin.

First he buzzed over the Potomac, a humble bug among all the limousine dragonflies, to take a look at the Pentagon. From the parking lot he gazed at one of the five sides of the complex, built in classic penitentiary style, with qualified admiration.

‘There you are,’ he said to Valentina, ‘the United States Department of Defence. Or War,’ he added.

Unsolicited statistics lit up in his brain like figures on a computer. ‘The world’s second largest building,’ he recited. ‘Did you know that they take 190,000 phone calls a day in there? And that they have 4,200 clocks and 685 water fountains?’

‘Really?’ The sarcasm was gentle. ‘And how many cups of coffee do they drink a day?’

‘Thirty thousand,’ Zhukov said promptly, grinning apologetically.

‘It’s strange to think they could be speaking to the Kremlin right now.’

Zhukov looked at his watch. 3 p.m. ‘They probably are. Every hour on the hour they test the teletype machines. The messages are very reassuring. I read, for instance, that one test message from the Americans on the hot line was a four-stanza poem by Robert Frost—“Desert Places”.’

‘And what did the Kremlin reply with?’

‘Excerpts in Russian from a Chekhov short story about birch trees. I understand twenty messages passed between Washington and Moscow during the Arab-Israeli war. They probably averted a world war on those teletypes.’

‘Who sent the first message?’

He patted her knee. ‘Premier Kosygin.’ He was pleased about that, too. ‘And the President keeps the messages in a green leather album as a memento.’ Statistics and trivia for ever accumulating in the filing cabinet of his brain; substitutes for the sonnets he once planned to deposit there.

He pointed the Volkswagen towards the ghetto. Losing himself a couple of times in the graceful geometry, driving along 15th in which a flourishing bookshop was separated from the White House by the protective bulk of the Treasury Department; finding 14th and following its route, its lament, to the Negro quarter.

In the Saturday afternoon quiet it was an abandoned place. A discarded screen set, a pool scummy with neglect. Tenements leaning, small shop windows rheumy. A few blacks strolling to nowhere; not a white face in sight.

Valentina said, ‘Can we get out and walk?’

Zhukov shook his head. ‘They advised me not to.’

‘We wouldn’t come to any harm.’

‘Why not? Because we’re Russians? Red Panthers? How would they know? You can’t explain after you’ve been knocked unconscious.’

‘I think it’s exaggerated. They don’t look very dangerous.’

Like many women she had the knack of converting discretion into cowardice. ‘The ambassador’s wife in New York thought the dangers of Central Park were exaggerated and she was mugged there.’

‘Mugged? You sound very American, Vladimir.’

‘I try to speak their language—it’s my job.’

They stopped at a red light, the stubby car vulnerable in the listlessly hostile street. An old Pontiac slid up beside them, the black driver grinning at them without friendliness. A snap-brimmed hat was tilted on the back of his head, one elbow rested outside the window with self-conscious nonchalance. But you couldn’t see his eyes; only your own reflection in the mirrors of his glasses. Chewing, grinning, he spat towards the Volkswagen as the lights changed and took off fast, tyres screaming, briefly victorious over white trash.

This flaking road, Zhukov thought, led to the deep south. There were still mounds of soiled snow on the sidewalk, but the disease of the place was tropical, leprosy, sleeping sickness, the wasting of cholera.

He turned into a residential street where pride was resurrected. Terraces of clean red brick and portals and verandas for summertime courting and grizzled remembering. And cars slumbering outside.

He drove on, rounded a block, returning to 14th.

Waiting for the lights to change, a girl of sixteen or so danced to the beat of distant rhythms. Dressed to kill in a black leather micro skirt with tassels swinging and a red breasty sweater; no coat on this cold and dead day. She may not have known she was dancing—as conscious of her rhythm as she was of her heartbeat. Words unwritten—‘I don’t give a damn, I don’t give a damn.’ Breasts bobbing, buttocks taut under black leather. Fingers flicking, orange baubles of ear-rings bouncing. She felt them staring; the rhythms froze, the smile, a snarl. She said something but they couldn’t hear. An obscenity, no doubt, in this hopeless place.

Valentina sat tensely. ‘It was like this,’ she said, ‘before the Revolution. Streets like this are deceptive. This is where it’s happening.’ She pointed behind shutters, behind walls. ‘And why not? Compare these streets with the streets of Bethesda, Georgetown, Alexandria.’

‘At least the Government is trying to do something about it.’

‘They. Trying? It’s not even their city, Vladimir. Where are those statistics of yours? How many Negroes and how many whites in Washington?’

‘Five hundred thousand Negroes,’ Zhukov admitted. ‘And 300,000 whites. Something like that. But they are trying, Valentina. Schools, housing, black mayors, black politicians. What more can they do?’

‘Get out of Vietnam and use the money to help their own people.’

For God’s sake, he wanted to cry out. Stop strangling yourself with politics. To hell with bloody politics. Wasn’t Russia doing the same as America? Grabbing millions of roubles for armaments and the race into space while her people stood in line for shabby overcoats, steel teeth, sprouting potatoes, shoes like polished cardboard. What’s more, if Russia had been faced with a crucial problem none of the black dissident meetings behind closed shutters would have been allowed. The rebels would have been chopping wood and sinking mines in the lost camps of Siberia. (He was surprised that he permitted such thoughts.)

He wanted to hurry away from the ghetto where all sympathy was spurned. ‘Maybe,’ he said, ‘you would like an apartment here among the blacks.’

She didn’t reply; his Valentina, companion for twenty years, mother of their only child, Natasha. Valentina—the soul of mother Russia, her wild song confined to a monotone by rules. So that she hardly recognized her own small hypocrisies any more.

‘Would you like that?’ he persisted. ‘Would you like an apartment here? You could do a lot of good work among these people.’ He rubbed her cheek lightly with the back of his hand.

‘Don’t be foolish, Vladimir. You know it would be impracticable.’ But she smiled at him and held his hand to her cheek for a moment. ‘How could a diplomat live in a Negro ghetto?’

Another red light stopped them. Vladimir noticed a group of black teenagers lounging in the doorway of a dead-eyed shop. Apprehension stirred. He peered to the left and right to see if he could jump the light. Indisputably with more cowardice than discretion. The spirit of Leningrad, Vladimir Zhukov! He wound down the window of the bug with bravado.

The young men were gathered on the opposite side of the intersection. One of them, hair combed out in black wings around his ears, held up a clenched fist. ‘Hello, whitey,’ he shouted. Too much to hope that they would recognize the diplomatic plates. Vladimir Zhukov, soldier and diplomat, called back, ‘Hallo there.’

‘Why,’ said the leader in a brown leather jacket, ‘this chalk wants to be friendly. A friendly whitey! Ain’t that something. What do you want, whitey—a nigger chick to screw?’

Zhukov implored the lights to change, but they remained steadfastly red.

‘Please drive on,’ Valentina urged him.

‘I thought you wanted to get out and walk. Meet the people.’

‘Don’t be stupid, Vladimir. Drive on before they attack us.’

Zhukov wound up the window. But he refused to drive on against the lights. Why, he couldn’t determine. Some gritty Soviet, Kazakh perversity. Had the lights jammed?

From the pocket of his pink satin jeans the leader took a slingshot. Sighted with deliberation and pulled back the lethal rubber.

The lights changed. Zhukov jammed his foot on the accelerator, the stone smacked the windscreen drilling a small hole and frosting the glass.

But they were away. As he drove Zhukov punched out the glass. His hands were shaking and his foot on the accelerator was wobbly.

In the driving mirror he saw them in the middle of the road, fists raised in panther salutes, faces triumphant.

‘Do you still want to live here?’

‘Please, Vladimir.’

He noticed a trickle of blood on her cheekbone.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘Is it serious?’

‘It’s nothing. The stone just grazed me.’

‘Shall I take you to a hospital.’

‘I told you—it’s nothing.’ She reached back and picked up the stone lying on the back seat. A small sharp flint.

On the sidewalk Zhukov saw a drunken old man with a folded black face and a jockey cap picking up a cigarette butt from the gutter. Through a vista ahead he briefly saw the tip of the noble white dome of the Capitol.

6

IT was a perfect night for spying, socializing, intriguing and electioneering in Washington, D.C.—activities which blended easily into an entity in the capital city. A fine frosty night; the sky filled with calculating stars, the sidewalks glittering with jewels.

At the black-tie affairs in the mansions and palaces around Massachusetts Avenue—held simultaneously with clandestine meetings in the ghetto where they were plotting to overthrow the whole elegant caboosh—the organization was as smooth as a butler’s voice. Although this evening there was some unfortunate coincidence because there were affairs at both the French and the Spanish Embassies and a select dinner at the White House garnished with rumours that, over liqueurs, there might be an important leak about the President’s intentions in the election. (During the day, Richard Nixon, vying for the Republican nomination, had promised in a speech in New Hampshire to finish the war in Vietnam with these words, ‘I pledge to you that the new leadership the Republicans offer will end the war and win the peace in the Pacific.’)

God knows how the clash occurred. The French and the Spaniards were both highly desirable invitations for palate and prestige and it was surely a prima facie case for establishing a clearing house for such occasions. Even the current in hostess (wife of a Mid West crusading senator), whose blunt wit had made her some sort of reputation was in a quandary. She had planned first a few pithy but serious words of advice for Franco which would be relayed to the Generalissimo; then the French invitation had arrived and she had composed some saucy directives for de Gaulle; then, deciding to visit both and fearing that she might confuse her messages, she had resolved to crystallize her words into two well-timed cracks that could apply to either leader. Thank heavens, she thought under the drier at Jean-Paul’s, that through some bureaucratic oversight they had forgotten to invite her to the White House dinner.

Elsewhere in Pierre l’Enfant’s dream city the beautiful, the ambitious, the dedicated, the sycophantic, the established and the insecure, pondered the invitations. Democrats and Republicans, the Chief Justice, the Secretary of State (thankfully committed to the White House), the Attorney General, several ministers, umpteen advisers, Congressmen, journalists, a pet author, a vivacious pop singer, some aristocracy from Britain, a couple of Italian diplomats of impeccable lechery, all the ambassadors and many of their henchmen, innumerable spies, innumerable courtesans, a general or two, lawyers seeking slander, some widows still game at sixty, a couple of Mafia junior officers disgusted by so much overt intrigue, the F.B.I., the C.I.A. and the K.G.B., a blackmailer, one virgin, half a dozen TV producers, their sons and daughters, and there among them all maybe a future president or two.

Almost everyone omitted from the White House invitation list elected to attend both receptions. Thus the problem became simply one of strategy: which to attend first? Because the implied insult of visiting one’s host second was worse than declining the invitation altogether. The in hostess decided to grace the Spanish reception first and explain to the French that she had been asked to deliver an urgent message to Prince Juan Carlos, heir apparent to the Spanish throne.

At the Russian Embassy the debate was less refined. It was merely a question of who was to be let out on a leash for the night. Among the few given a pass was Vladimir Zhukov because his new duties entailed mixing with the Beautiful People.

With his paranoid conviction that, like himself, everyone was a potential eavesdropper, Mikhail Brodsky chose an open-air venue for the briefing. They met on the steps of the Capitol.

‘Greetings comrade,’ Brodsky said in his imprisoned voice.

Zhukov nodded, almost a first secretary now.

‘Shall we walk? It’s such a fine morning and Washington is a beautiful place on a day like this.’

As indeed it was, Zhukov thought. Velvet buds enticed by the thaw, trees straining for summer, the Roman dome of the Capitol gleaming in the sunlight, Stars and Stripes rippling against the winter-blue sky, frost melting on the city’s recuperating carpets. Over all this nobility an airliner lingered like a spent match. He remembered Leningrad, another noble city, on mornings like this.

‘Why all this secrecy?’ Zhukov demanded. ‘I nearly didn’t come.’

‘You are perhaps feeling your authority now that you are nearly a first secretary?’

Zhukov shrugged. ‘You, after all, are only a third secretary.’

They turned into the Botanical Gardens. (Ninety varieties of azaleas, 500 kinds of orchid, Zhukov’s computer reminded him.)

Brodsky was silent for a while. Smarter than usual in a light grey overcoat and plaid scarf. His hat and his poor shoes and, somehow, his gold-rimmed spectacles the give-away. Finally he said: ‘You are doing very well, Comrade Zhukov. But you mustn’t get drunk with power.’ He giggled.

‘A first secretary can hardly do that.’

‘But you mustn’t forget that position is nothing in the Soviet System. We do not recognize the cult of personality on any level.’ He tucked a lock of girlish hair under his hat. ‘And you mustn’t forget that some of the least significant members of the Party have certain other authorities.’ His voice iced up. ‘You could be demoted just as easily as you have been promoted. In fact, in certain circumstances, you could be put on a plane back to Moscow within a few hours. Tonight for instance.’

‘I doubt it,’ Zhukov said without conviction.

They walked slowly down Capitol Hill, and Brodsky assured him that no such move was anticipated because it was well known that Zhukov was a loyal servant of the Party and the Soviet Union. And he reverted to the tentative approaches made in Moscow about extensions of his official duties in Washington.

Zhukov remembered the approaches. ‘You may be asked to mix a little. To make friends in the right places. To socialize just a little more than some of your colleagues. After all, we have to keep contact with our hosts and you are an excellent linguist …’

Brodsky danced over a fallen branch. ‘They no doubt put it very vaguely. And, of course, at that time you were only going to be our second-string socialite. Until the Tardovsky fiasco. Now you have taken his place. Because you have a certain charm, because you are a man of sensitivity and comparative sophistication. In short, Comrade Zhukov, you are an attractive and articulate man.’

‘You are very kind.’ Perhaps Brodsky had some homosexual inclinations? ‘Do you mean you want me to become a spy?’

‘Nothing so dramatic. If we—they—had wanted you to become a spy your training in Moscow would have been far more rigorous. No, we do not want you to arrange any drops on the Bronx subway or under the railway bridge at Queens.’ He paused, conscious of vague indiscretion. ‘Those two drops, incidentally, have been abandoned.’ He stopped to light a cigarette. ‘No, it will merely be a matter of mixing. Becoming known as an unusually extrovert Russian, a valuable catch for the hostesses.’ He grinned sideways at Zhukov. ‘You may even recite some of your poetry.’

They arrived at the Monument reaching for a fragment of cloud. ‘The tallest masonry structure in the world,’ Zhukov supplied. ‘And for what purpose am I to do all this socializing?’ Although, of course, he knew.

You are not such a naïve man, Comrade Zhukov. However, I will elaborate.’

A line of schoolchildren accompanied by a pretty and enthusiastic young teacher passed them, headed for the Monument fringed at its base with a circle of Old Glories. Brodsky regarded children and teacher with distaste.

Zhukov said, ‘I presume you want me to assess opinion and trends.’

‘Exactly so,’ Brodsky said. ‘To take the pulse of Washington as it were. You will find many Americans and other diplomats anxious to make friends with you because a socializing Russian is something of a rarity in Washington.’ He squeezed Zhukov’s bicep for no particular reason that Zhukov could determine. ‘Most of us have to go straight home. In any case’—an explosion of mirth like suppressed laughter escaping in a classroom—‘can you imagine Comrade Grigorenko at a cocktail party?’

Zhukov said he couldn’t.

Brodsky continued: ‘Many of your new friends will, of course, be trying to feel the pulse of the Soviet Embassy through you. You will naturally supply their wants—after we have decided what they should be told.’

‘Is that all?’

‘Not quite.’ The saliva froze again. ‘In Washington there are always weak men in low places with access to valuable information. However diligently they are screened they manage to hide their weaknesses.’ He stared at Zhukov from behind his scholarly glasses. ‘We screened you very carefully but we could not reach your soul.’ He lit another cigarette—American, Zhukov noted. ‘Such people seem to flourish on the party circuit. Men and women. It will be your responsibility to listen for indiscretions, because these people respond to sympathy, particularly on the third Martini. You will make friends with them,’ Brodsky ordered.

‘So I am to be a spy?’

‘Far from it. Merely a specialist in judicious fraternizing. The social bear of the Soviet Embassy.’

‘An agent provocateur?’

‘A theatrical term and out-of-date. You’re hardly the type to be a masculine Mata Hari. In any case most of the spying is carried out by the lesser embassies these days. You will primarily remain a diplomat with an extension of duties which is not, after all, confined to Soviet diplomats. You will merely be our representative—or one of our representatives—in this field. You see,’ he explained, ‘we leave the heavyweight operations to the military attachés—every country does. The more devious work to our friends in other embassies. We carry out duties of a more dignified nature.’

A women’s club passed by on their way to the Monument. Brodsky’s distaste deepened to disgust.

‘Supposing I am not fitted to these duties?’ Zhukov asked.

‘We—they—feel that you are. Or rather you’re the best candidate there is in the embassy.’

Zhukov knew that it was futile to refuse. ‘And what am I supposed to do about these … these weaklings, when I meet them?’

‘Report their weaknesses to us. Determine how they can be blackmailed. Men, women, alcohol, money … every American with two cars wants three, every American with a co-op wants a town house. But,’ he added, ‘I used the term weak loosely. You may meet strong men seeking only an outlet to contribute to the glorious cause of Socialism.’ His glasses glinted in the sunlight. ‘Their strength may be their determination to supply us with information despite the risks involved.’

‘Traitors, you mean?’

The grip on Zhukov’s bicep was reapplied, unexpected strength in the delicate fingers. ‘Sometimes I am surprised by your reactions, Comrade Zhukov.’

Zhukov shrugged—it wasn’t in his character to apologize. Then inspiration came to him on this inspired morning. ‘I have a daughter in the Soviet Union, Comrade Brodsky.’

Brodsky looked surprised. ‘I am aware of that. As a matter of fact I was going to mention her …’

‘Mention Natasha? Why?’ Alarm curdled into nausea.

‘It doesn’t matter for the moment. What were you going to say?’

‘Tell me why you were going to mention Natasha?’ Sweet, innocent Natasha with her mother’s loveliness and her father’s questing spirit.

‘No, comrade, you first.’

Zhukov’s voice faltered. ‘I was merely going to ask if you thought it would be possible for her to visit us here this year.’