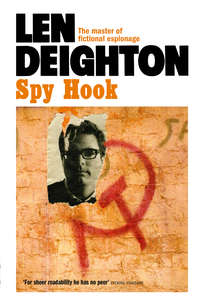

Spy Hook

‘Precisely,’ said the Deputy. ‘I think we’d all like to hear your views, Samson.’

I played for time. ‘From Berlin Field Unit?’ I said. ‘Or from somewhere else?’

‘I don’t think BFU should come into this,’ said Strang hastily. That was the voice of Operations.

He was right of course. Sending someone from West Berlin into such a situation would be madness. In a region like that any kind of stranger is immediately scrutinized by every damned secret policeman on duty and a few that aren’t. ‘You’re probably right,’ I said as if conceding something.

Strang said, ‘They’d have him in the slammer before the ink was dry on the hotel register.’

‘We have people nearer,’ said the Deputy.

They were all looking at me now. This is why they’d waited for me to join them. They knew what the answer was going to be but they were going to make sure that it was me, an ex-Field Man, who would say it out loud. Then they could get on with their work, or their lunch, or doze off until the next crisis.

‘We can’t just leave them to it,’ I said.

They all nodded. We had to agree the wrong answer first, that was the ethic of the Department.

‘We’ve had good stuff from them,’ Dicky said. ‘Nothing big of course, they are only foundry workers, but they’ve never let us down.’

‘I’d like to hear what Samson thinks,’ said the Deputy. He had a slim gold pencil in his hand. He was leaning back in his chair, arm extended to his notepad. He looked up from whatever he was writing, stared at me and smiled encouragement.

‘We’ll have to let it go,’ I said finally.

‘Speak up,’ said the Deputy in his housemaster voice.

I cleared my throat. ‘There’s nothing we can do,’ I said rather louder. ‘We’ll just have to wait and see.’

They all turned to see the Deputy’s reaction. ‘I think that’s sound,’ he said at last. Dicky Cruyer smiled with relief at someone else making the decision. Especially a decision to do nothing. He wriggled about and ran his hand back through his curly hair, looking round the room and nodding. Then he looked over to where a clerk was keeping an account of what was said, to be sure he was writing it down.

Well I’d earned my wages for the day. I’d told them exactly what they wanted to hear. Now nothing would happen for a day or so, apart from a group of Polish workers having their fingernails torn out under hygienic conditions with a shorthand writer in attendance.

There was a knock at the door and a tray with tea and biscuits arrived. Billingsly, perhaps because he was the youngest and least arthritic of us, or because he wanted to impress the Deputy, distributed the cups and saucers and passed the milk and teapot along the polished table top.

‘Chocolate oatmeal!’ said Harry Strang. I looked up at him and he winked. Harry knew what it was all about. Harry had spent enough time at the sharp end to know what I was thinking.

Harry poured tea for me. I took it and drank some. It turned to acid in my stomach. The Deputy was leaning towards Billingsly to ask him something about the excessive ‘down time’ the computers in the Yellow Submarine were suffering lately. Billingsly said that you had to expect some trouble with these ‘electronic toys’. The Deputy said not when you paid two million pounds for them you didn’t.

‘Biscuit?’ said Harry Strang.

‘No thanks.’

‘You used to like chocolate oatmeal as I remember,’ he said sardonically.

I leaned over to see what the Deputy had written on his notepad but it was just a pattern: a hundred wobbly concentric circles with a big dot in the middle. No escape; no solution; no nothing. It was the answer he wanted to his question, I suppose, and I had given it to him. Ten marks out of ten, Samson. Advance to Go and collect two hundred pounds.

It was only when the Deputy had finished his tea that protocol permitted even the busiest of us to take our leave. Just when the Deputy was moving towards the door, Morgan – the D-G’s most obsequious acolyte – came in flush-faced and complete with Melton overcoat carrying, like an altar candle, one of those short unfolding umbrellas. He said, in his singsong Welsh accent, ‘Sorry I’m late, sir. I had the most awful and unexpected trouble with the motorcar.’ He bit his lip. Exertion and anxiety had made his face even paler than usual.

The Deputy was annoyed but allowed no more than a trace of it to show. ‘We managed without you, Morgan,’ he said.

As the Deputy marched out Morgan looked at me with a deep hatred that he made no attempt to hide. Perhaps he thought his humiliation was all my fault or perhaps he blamed me for being there when it happened. Either way, if the Department ever needed someone to bury me Morgan would be an enthusiastic volunteer. Perhaps he was already working on it.

I went downstairs, relieved to get out of that meeting even if it meant sitting in my cramped little office and trying to see over the top of the uncompleted paperwork. I stared at the cluttered table near the window, and more specifically at two boxes in beautiful Christmas wrappings, one marked ‘Billy’ and the other ‘Sally’. They’d been delivered by the Harrods van together with the cards that said ‘With dearest love from Mummy’ but not in Fiona’s hand-writing. I should have given them to the children before Christmas but I’d left them there and tried not to look at them. She’d sent presents on previous Christmases and I’d put them under the tree. The children had read the cards without comment. But this year we’d spent Christmas in our new little home and somehow I didn’t want Fiona to intrude into it. The move had given me a chance to get rid of Fiona’s clothes and personal things. I wanted to start again, but that didn’t make it any easier to confront those two bright boxes waiting for me every time I went into my office.

My desk was a mess. My secretary, Brenda, had been covering for two filing clerks who were sick or pregnant or some damned thing, so I tried to sort out a week of muddle that had accumulated on my desk in my absence.

The first things I came across were the red-labelled ‘urgent’ messages about Prettyman. My God, last Thursday there must have been new messages, requests, assignments and words of advice landing on my desk every half hour. Thank heavens Brenda had enough sense not to forward it all to Washington. Well, now I was back in London, and they could get someone else to go and bully Jim Prettyman into coming back here to be roasted by a committee of time-serving old flower-pots from Central Funding who were desperately looking for some unfortunate upon whom to dump the blame for their own inadequacies.

I was putting it all into the classified waste when I noticed the signature. Billingsly. Billingsly! It was damned odd that Billingsly hadn’t mentioned it to me this morning in Number Two Conference Room. He hadn’t even asked me what happened. His passion, if not to say obsession, for getting Prettyman here had undergone some abrupt traumatic change. That was the way it went with people like Billingsly – and many others in the Department – who alternated displays of panic and amnesia with disconcerting suddenness.

I threw the notes into the basket and forgot about it. There was no point in stirring trouble for Jim Prettyman. In my opinion he was a fool to suddenly get on his high horse about something so mundane. He could have testified and been the golden boy: he could have declined without upsetting them. But I think he liked confrontation. I decided to smooth things over as much as I could. When it came to writing the report I wouldn’t say he’d refused point-blank: I’d say he was thinking about it. Until they asked for the report, I’d say nothing at all.

I didn’t see Gloria until we had lunch together in the restaurant. Her fluent Hungarian had recently brought her a job downstairs: promotion, more pay and much more responsibility. I suppose they thought that it would be enough to make her forget the promises they’d made about paying her wages while she was at Cambridge. Her new job meant that I saw much less of her and so lunch had become the time when our domestic questions were settled: would it look too pushy to invite the Cruyers for dinner? Who had the receipt for the dry-cleaning? Why had I opened a new tin of cat-food for Muffin when the last one was still half-full?

I asked her if anything more had been said about her resignation, secretly hoping, I suppose, that she might have changed her mind. She hadn’t. When I broached the subject over the ‘mushroom quiche with winter salad’ she told me that she’d had an answer from a friend of hers about some comfortable rooms in Cambridge that she could probably rent.

‘What am I going to do with the house?’

‘Not so loud, darling,’ she said. We kept up this absurd pretence that our co-workers – or such of them as might be interested – didn’t know we were living together. ‘I’ll keep paying half the rent. I told you that.’

‘It’s nothing to do with the rent,’ I said. ‘It’s simply that I wouldn’t have taken on a place out in the sticks so I could sit there every night on my own, watching TV and saving up my laundry until I’ve got enough to make a full load for the washing machine.’

That produced the flicker of a grin. She leaned closer to me and said, ‘After you find out how much dirty laundry the children have every day, you won’t be worrying about filling up the machine: you’ll be looking for a place where you can get washing powder wholesale.’ She sipped some apple juice with added vitamin C. ‘You’ve got a nanny for the children. You’ll have that nice Mrs Palmer coming in every day to tidy round. I’ll be back every weekend: I don’t know what you are worrying about.’

‘I wish you’d be a little more realistic. Cambridge is a damned long way away from Balaklava Road. The weekend traffic will be horrendous, the railway service is even worse and in any case you’ll have your studying to do.’

‘I wish I could make you stop worrying,’ she said. ‘Are you ill? You haven’t been yourself since coming back from Washington. Did something go wrong there?’

‘If I’d known what you were going to do I would have made different plans.’

‘I told you. I told you over and over.’ She looked down and continued to eat her winter salad as if there was no more to be said. In a way she was right. She had told me time and time again. She’d been telling me for years that she was going to go to Cambridge and get this honours degree in PPE that she’d set her heart on. She’d told me so many times that I’d long since ceased to give it any credence. When she told me that she’d actually resigned I was astounded.

‘I thought it would be next year,’ I said lamely.

‘You thought it would be never,’ she said curtly. Then she looked up and gave me a wonderful smile. One thing about this damned business of going to Cambridge. It had put her into an incomparably sunny mood. Or was that simply the result of seeing me discomfited?

3

It was Gloria’s evening for visiting parents. Tuesday she had an evening class in mathematics, Wednesday economics and Thursday evening she visited her parents. She apportioned time for such things, so that I sometimes wondered if I was one of her duties, or time off.

I stayed working for an extra hour or so until there was a phone call from Mr Gaskell, a recently retired artillery sergeant-major who’d taken over security duties at reception. ‘There is a lady here. Asking for you by name. Mr Samson.’ The security man’s hoarse whisper was confidential to the point of being conspiratorial. I wondered if this was in deference to my professional or social obligations.

‘Does she have a name, Mr Gaskell?’

‘Lucinda Matthews.’ I had the feeling that he was reading from the slip that visitors have to fill out.

The name meant nothing to me but I thought it better not to say so. ‘I’ll be down,’ I said.

‘That would be best,’ said the security man. ‘I can’t let her upstairs into the building. You understand, Mr Samson?’

‘I understand.’ I looked out of the window. The low grey cloud that had darkened the sky all day seemed to have come even lower, and in the air there were tiny flickers of light; harbingers of the snow that had been forecast. Just the sight of it was enough to make me shiver.

By the time I’d locked away my work, checked the filing cabinets and got down to the lobby the mysterious Lucinda had gone.

‘A nice little person, sir,’ Gaskell confided when I asked what the woman was like. He was standing by the reception desk in his dark blue commissionaire’s uniform, tapping his fingers nervously upon the pile of dog-eared magazines that were loaned to visitors who spent a long time waiting here in the draughty lobby. ‘Well turned-out; a lady, if you know my meaning.’

I had no notion of his meaning. Gaskell spoke a language that seemed to be entirely his own. He was especially cryptic about dress, rank and class, perhaps because of the social no-man’s-land that all senior NCOs inhabit. I’d had these elliptical utterances from Gaskell before, about all kinds of things. I never knew what he was talking about. ‘Where did she say she’d meet me?’

‘She’d put the car on the pavement, sir. I had to ask her to move it. You know the regulations.’

‘Yes, I know.’

‘Car bombs and that sort of thing.’ No matter how much he rambled, his voice always had the confident tone of an orderly room: an orderly room under his command.

‘Where did she say she’d meet me?’ I asked yet again. I looked out through the glass doors. The snow had started and was falling fast and in big flakes. The ground was cold, so that it was not melting: it was going to lie. It didn’t need more than a couple of cupfuls of that sprinkled over the Metropolis before the public transportation systems all came to a complete halt. Gloria would be at her parents’ house by now. She’d gone by train. I wondered if she’d now decide to stay overnight at her parents’, or if she’d expect me to go and collect her in the car. Her parents lived at Epsom; too damned near our little nest at Raynes Park for my liking. Gloria said I was frightened of her father. I wasn’t frightened of him, but I didn’t relish facing intensive questioning from a Hungarian dentist about my relationship with his young daughter.

Gaskell was talking again. ‘Lovely vehicle. A dark green Mercedes. Gleaming! Waxed! Someone is looking after it, you could see that. You’d never get a lady polishing a car. It’s not in their nature.’

‘Where did she go, Mr Gaskell?’

‘I told her the best car park for her would be Elephant and Castle.’ He went to the map on the wall to show me where the Elephant and Castle was. Gaskell was a big man and he’d retired at fifty. I wondered why he hadn’t found a pub to manage. He would have been wonderful behind a bar counter. The previous week, when I’d been asking him about the train service to Portsmouth, he’d confided to me – amid a barrage of other information – that that’s what he would have liked to be doing.

‘Never mind the car park, Mr Gaskell. I need to know where she’s meeting me.’

‘Sandy’s,’ he said again. ‘You knew it well, she said.’ He watched me carefully. Ever since our office address had been so widely published, thanks to the public-spirited endeavours of ‘investigative journalists’, there had been strict instructions that staff must not frequent any local bars, pubs or clubs because of the regular presence of eavesdroppers of various kinds, amateur and professional.

‘I wish you’d write these things down,’ I said. ‘I’ve never heard of it. Do you know where she means? Is it a café, or what?’

‘Not a café I’ve heard of,’ said Gaskell, frowning and sucking his teeth. ‘Nowhere near here with a name like that.’ And then, as he remembered, his face lit up. ‘Big Henry’s! That’s what she said: Big Henry’s.’

‘Big Henty’s,’ I said, correcting him. ‘Tower Bridge Road. Yes, I know it.’

Yes, I knew it and my heart sank. I knew exactly the kind of ‘informant’ who was likely to be waiting for me in Big Henty’s: an ear-bender with open palm outstretched. And I had planned an evening at home alone with a coal fire, the carcass of Sunday’s duck, a bottle of wine and a book. I looked at the door and I looked at Gaskell. And I wondered if the sensible thing wouldn’t be to forget about Lucinda, and whoever she was fronting for, and drive straight home and ignore the whole thing. The chances were that I’d never hear from the mysterious Lucinda again. This town was filled with people who knew me a long time ago and suddenly remembered me when they needed a few pounds from the public purse in exchange for some ancient and unreliable intelligence material.

‘If you’d like me to come along, Mr Samson …’ said Gaskell suddenly, and allowed his offer to hang in the air.

So Gaskell thought there was some strong-arm business in the offing. Well he was a game fellow. Surely he was too old for that sort of thing: and certainly I was.

‘That’s very kind of you, Mr Gaskell,’ I said, ‘but the prospect is boredom rather than any rough stuff.’

‘Whatever you say,’ said Gaskell, unable to keep the disappointment from his voice.

It was the margin of disbelief that made me feel I had to follow it up. I didn’t want it to look as if I was nervous. Dammit! Why wasn’t I brave enough not to care what the Gaskells of this world thought about me?

Tower Bridge Road is a major south London thoroughfare that leads to the river, or rather to the curious neo-Gothic bridge which, for many foreigners, symbolizes the capital. This is Southwark. From here Chaucer’s pilgrims set out for Canterbury; and a couple of centuries later Shakespeare’s Globe theatre was built upon the marshes. For Victorian London this shopping street, with a dozen brightly lit pubs, barrel organs and late-night street markets, was the centre of one of the capital’s most vigorous neighbourhoods. Here filthy slums, smoke-darkened factories and crowded sweat-shops stood side by side with neat leafy squares where scrawny clerks and potbellied shopkeepers asserted their social superiority.

Now it is dark and squalid and silent. Well-intentioned bureaucrats nowadays sent shop assistants home early, street traders were banished, almost empty pubs sold highly taxed watery lager and the factories were derelict: a textbook example of urban blight, with yuppies nibbling the leafy bits.

Back in the days before women’s lib, designer jeans and deep-dish pizza, Big Henty’s snooker hall with its ‘ten full-size tables, fully licensed bar and hot food’ was the Athenaeum of Southwark. The narrow doorway and its dimly lit staircase gave entry to a cavernous hall conveniently sited over a particularly good eel and pie shop.

Now, alas, the eel and pie shop was a video rental ‘club’ where posters in primary colours depicted half-naked film stars firing heavy machine guns from the hip. But in its essentials Big Henty’s was largely unchanged. The lighting was exactly the same as I remembered it, and any snooker hall is judged on its lighting. Although it was very quiet every table was in use. The green baize table tops glowed like ten large aquariums, their water still, until suddenly across them brightly coloured fish darted, snapped and disappeared.

Big Henty wasn’t there of course. Big Henty died in 1905. Now the hall was run by a thin white-faced fellow of about forty. He supervised the bar. There was not a wide choice: these snooker-playing men didn’t appreciate the curious fizzy mixtures that keep barmen busy in cocktail bars. At Big Henty’s you drank whisky or vodka; strong ale or Guinness with tonic and soda water for the abstemious. For the hungry there were ‘toasted’ sandwiches that came soft, warm and plastic-wrapped from the microwave oven.

‘Evening, Bernard. Started to snow, has it?’ What a memory the man had. It was years since I’d been here. He picked up his lighted cigarette from the Johnny Walker ashtray, and inhaled on it briefly before putting it back into position. I remembered his chain-smoking, the way he lit one cigarette from another but put them in his mouth only rarely. I’d brought Dicky Cruyer here one evening long ago to make contact with a loud-mouthed fellow who worked in the East German embassy. It had come to nothing, but I remember Dicky describing the barman as the keeper of the sacred flame.

I responded, ‘Half of Guinness … Sydney.’ His name came to me in that moment of desperation. ‘Yes, the snow is starting to pile up.’

It was bottled Guinness of course. This was not the place that a connoisseur of stout and porter would come to savour beverages tapped from the wood. But he poured it down the side of the glass holding his thumb under the point of impact to show he knew the folklore, and he put exactly the right size head of light brown foam upon the black beer. ‘In the back room.’ Delicately he shook the last drops from the bottle and tossed it away without a glance. ‘Your friend. In the back room. Behind Table Four.’

I picked up my glass of beer and sipped. Then I turned slowly to survey the room. Big Henty’s back room had proved its worth to numerous fugitives over the years. It had always been tolerated by authority. The CID officers from Borough High Street police station found it a convenient place to meet their informants. I walked across the hall. Beyond the tasselled and fringed lights that hung over the snooker tables, the room was dark. The spectators – not many this evening – sat on wooden benches along the walls, their grey faces no more than smudges, their dark clothes invisible.

Walking unhurriedly, and pausing to watch a tricky shot, I took my beer across to table number four. One of the players, a man in the favoured costume of dark trousers, loose-collared white shirt and unbuttoned waistcoat, moved the scoreboard pointer and watched me with expressionless eyes as I opened the door marked ‘Staff’ and went inside.

There was a smell of soap and disinfectant. It was a small storeroom with a window through which the snooker hall could be seen if you pulled aside the dirty net curtain. On the other side of the room there was another window, a larger one that looked down upon Tower Bridge Road. From the street below there came the sound of cars slurping through the slush.

‘Bernard.’ It was a woman’s voice. ‘I thought you weren’t going to come.’

I sat down on the bench before I recognized her in the dim light. ‘Cindy!’ I said. ‘Good God, Cindy!’

‘You’d forgotten I existed.’

‘Of course I hadn’t.’ I’d only forgotten that Cindy Prettyman’s full name was Lucinda, and that she might have reverted to her maiden name. ‘Can I get you a drink?’

She held up her glass. ‘It’s tonic water. I’m not drinking these days.’

‘I just didn’t expect you here,’ I said. I looked through the net curtain at the tables.

‘Why not?’

‘Yes, why not?’ I said and laughed briefly. ‘When I think how many times Jim made me swear I was giving up the game for ever.’ In the old days, when Jim Prettyman was working alongside me, he taught me to play snooker. He played an exhibition class game, and his wife Cindy was something of an expert too.

Cindy was older than Jim by a year or two. Her father was a steel worker in Scunthorpe: a socialist of the old school. She’d got a scholarship to Reading University. She said she’d never had any ambition but for a career in the Civil Service since her schooldays. I don’t know if it was true but it went down well at the Selection Board. She wanted Treasury but got Foreign Office, and eventually got Jim Prettyman who went there too. Then Jim came over to work in the Department and I saw a lot of him. We used to come here, me, Fiona, Jim and Cindy, after work on Fridays. We’d play snooker to decide who would buy dinner at Enzo’s, a little Italian restaurant in Old Kent Road. Invariably it was me. It was a joke really; my way of repaying him for the lesson. And I was the eldest and making more money. Then the Prettymans moved out of town to Edgware. Jim got a rise and bought a full-size table of his own, and then we stopped coming to Big Henty’s. And Jim invited us over to his place for Sunday lunch, and a game, sometimes. But it was never the same after that.