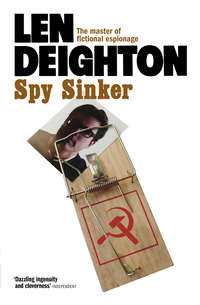

Spy Sinker

He lifted his eyes to the small painting that hung above the bed. He had many fine pictures – all by modern British painters – but this was Bret Rensselaer’s proudest possession. Stanley Spencer: buxom English villagers frolicking in an orchard. Bret could study it for hours, he could smell the fresh grass and the apple blossom. He’d paid far too much for the painting but he had desperately wanted to possess that English scene for ever. Nikki didn’t appreciate having a masterpiece enshrined in the bedroom, to love and to cherish. She preferred photographs; she’d admitted as much once, during a savage argument about the bills she’d run up with the dressmaker.

‘You said that running an agent into the Kremlin was your greatest ambition.’

‘Did I?’ He looked at her and blinked, discomposed both by the extent of his indiscretion and the naïveté of it. ‘I was kidding you.’

‘Don’t say that, Bret!’ She was angry that he should airily dismiss the only truly intimate conversation she could remember having with him. ‘You were serious. Dammit, you were serious.’

‘Perhaps you’re right.’ He looked at her and at the bedside table to see what she’d been drinking, but there was no alcohol there, only a litre-size bottle of Malvern water. She’d stuck to her rigorous diet – no bread, butter, sugar, potatoes, pasta or alcohol – for three weeks. She was amazingly disciplined about her dieting and Nikki had never been much of a drinker: it went straight to her waistline. When Internal Security had first vetted her they’d remarked her abstinence and Bret had been proud.

He got up and went round to her side of the bed to give her a kiss. She offered her cheek. It was a sort of armistice but his fury was not allayed: just repressed. ‘It’s a glorious sunny day again. I’m going to have coffee in the garden. Shall I bring some up?’

She pulled the bedside clock round to see it. ‘Jesus Christ! The help won’t be there for an hour yet.’

‘I’m perfectly capable of fixing my own toast and coffee.’

‘It’s too early for me. I’ll call for it when I’m ready.’

He looked at her eyes. She was close to tears. As soon as he left the room she would begin weeping. ‘Go back to sleep, Nikki. Do you want an aspirin?’

‘No I don’t want a goddamned aspirin. Anytime I bug you, you ask me if I want an aspirin: as if talking out of turn was some kind of feminine malady.’

He had often accused her of being a dreamer, which by extension was his claim to be a practical realist. The truth was that he was even more of a romantic dreamer than she was. This craving he had for everything English was ridiculous. He’d even talked of renouncing his US citizenship and was hoping to get one of these knighthoods the British handed out instead of money. An obsession of that kind could bring him only trouble.

There was enough work in the office to keep Bret Rensselaer busy for the first hour or more. It was a wonderful room on the top floor of a modern block. Large by the standards of modern accommodation, his office had been decorated according to his own ideas, as interpreted by one of the best interior decorators in London. He sat behind his big glass-topped desk. The colour scheme – walls, carpet and long leather chesterfield – was entirely grey and black except for his white phone. Bret had intended that the room should be in harmony with this prospect of the slate roofs of central London.

He buzzed for his secretary and started work. Halfway through the morning, his tray emptied by the messenger, he decided to switch off his phone and take twenty minutes to catch up with his physical exercises. It was a part of his puritanical nature and upbringing that he would not make a confrontation with his wife an excuse to miss his work or his exercises.

He was in his shirt-sleeves, doing his thirty pressups, when Dicky Cruyer – a contender for the soon to become vacant chair of the German Stations Controller – put his head round the door and said, ‘Bret, your wife has been trying to get through to you.’

Bret continued to do his pressups slowly and methodically. ‘And?’ he said, trying not to puff.

‘She sounded upset,’ said Dicky. ‘She said something like, “Tell him, you get your man in Moscow and I’ll go get my man in Paris.” I asked her to tell me again but she rang off.’ He watched while Bret finished a couple more pressups.

‘I’ll talk to her later,’ grunted Bret.

‘She was at the airport, getting on the plane. She said to say goodbye. “Goodbye for ever,” she said.’

‘So you’ve said it,’ Bret told him, head twisted, smiling pleasantly from his position full length on the floor. ‘Message received and understood.’

Dicky muttered something about it being a bad phone line, nodded and withdrew with the feeling that he’d been unwise to bring the ugly news. He’d heard rumours that all was not going well with the Rensselaer marriage, but no matter how much a man might want to leave his wife it does not mean that he wants her to leave him. Dicky had the feeling that Bret Rensselaer wouldn’t forget who it was who had brought news of his wife’s desertion, and it would leave a residual antipathy that would taint their relationship for ever after. In this assumption Dicky was correct. He began to hope that the appointment of the German Stations Controller would not be entirely in Bret’s gift.

The door clicked shut. Bret began the pressups over again. He had inflicted that mortifying rule on himself: if he stopped during exercises he did them all over again.

When his exercises were done Bret opened the door that concealed a small sink. He washed his face and hands and as he did so he recalled in detail the conversation he’d had with his wife that morning. He told himself not to waste time pondering the rift between them: what was gone was gone, and good riddance. Bret Rensselaer had always claimed that he never wasted time upon recriminations or regrets, but he felt hurt and deeply resentful.

To get his mind on other matters he began to think about those days long ago when he’d wanted to get into Operations. He’d drafted out some ideas about undermining the East German economy but no one had taken him seriously. The Director-General’s reaction to the big pile of research he’d done was to give him the European Economics desk. That wasn’t really something to complain about; Bret had built the desk into a formidable empire. But the economic desk work had been processing intelligence. He always regretted that they hadn’t taken up the more important idea: the idea of promoting change in East Germany.

Bret’s idea had never been to get an effective agent into the top of the Moscow KGB. He would prefer having a really brilliant agent, with a long-term disruptive and informative role, in East Berlin, the capital of the German Democratic Republic. It would take a long time: it was not something that could be hurried in the way that so many SIS operations were.

The Department probably had dozens of sleepers who’d established themselves, in one capacity or another, as longtime loyal agents of the various communist regimes of East Europe. Now Bret had to find such a person, and it had to be the right one. But the long and meticulous process of selection had to be done with such discretion and finesse that no one would be aware of what he was doing. And when he found that man, he’d have the task of persuading him to risk his neck in a way that sleepers were not normally asked to do. A lot of sleepers assigned to deep cover just took the money and relied upon the good chance that they’d never be asked to do anything at all.

It would not be simple. Neither would it be happy. At the beginning there would be little or no cooperation, for the simple reason that no one around him could be told what he was doing. Afterwards there would be the clamour for recognition and rewards. The Department was very concerned about such things. It was natural these men, who laboured so secretly, should strive so vigorously and desperately for the admiration and respect of their peers when things went well. And if things did not go well there would be the savage recriminations that accompanied post-mortems.

Lastly there was the effect that an operation like this would have upon the man who went off to do the dirty work. They did not come back. Or if they did come back they were never fit to work again. Of the survivors Bret had seen, few returned able to do anything but sit with a rug over their knees, talk to the officially approved departmental shrink, and try vainly to put together ruptured nerves and shattered relationships.

It was easy to see why they couldn’t recover. You ask a man to leave all that he holds most dear, to spy in a strange country. Then, years later, you snatch him back again – God willing – to live out his remaining life in peace and contentment. But there is no peace and no contentment either. The poor devil can’t remember anyone he hasn’t betrayed or abandoned at some time or another. Such people are destroyed as surely as if they’d faced a firing squad.

On the other hand it was necessary to balance the destruction of one man – plus perhaps a few members of his family – with what could be achieved by such a coup. It was a matter of the greater good of the community at large. They were fighting against a system which killed hundreds of thousands in labour camps, which used torture as a normal part of its police interrogation, which put dissenters into mental asylums. It would be absurd to be squeamish when the stakes were so high.

Bret Rensselaer closed the door that hid his sink and went to the window and looked out. Despite the haze, you could see it all from here: the Gothic spike of the Palace of Westminster, the spire of St Martin-in-the-Fields, Nelson balancing gingerly on his column. There was a unity to it. Even the incongruous Post Office tower would perhaps look all right given a century or so of weathering. Bret pushed his face close to the glass in order to see Wren’s dome of St Paul’s. The Director-General’s room had a fine view northwards and Bret envied him that. One day perhaps he would occupy that room. Nikki had made jokes about that and he’d pretended to laugh at them but he’d not given up hopes that one day …

Then he remembered the notes he’d made about the whole project. A great idea struck him: now that he had more time, and a staff of economists and analysts, he’d have it all up-dated. Maps, bar charts, pie charts, graphs and easy to understand figures that, even the Director-General would understand could all be done on the computer. Why hadn’t he thought of it before? Thank you, Nikki.

And that brought him back to his wife. Once again he told himself to be resolute. She had left him. It was all over. He told himself he’d seen it coming for ages but in fact he hadn’t seen it coming at all. He’d always taken it for granted that Nikki would put up with all the things of which she complained – just as he put up with her – in order to have a marriage. He would miss her, there was no getting away from that fact, but he vowed he wouldn’t go chasing after her.

It simply wasn’t fair: he’d never been unfaithful to her all the time they’d been married. He sighed. Now he would have to start all over again: dating, courting, persuading, cajoling, being the extra man at parties. He’d have to learn how to suffer rejection when he asked younger women out to dinner. Rejection had never been easy for him. It was all too awful to contemplate. Perhaps he’d get his secretary to dine with him one evening next week. She’d told him it was all off with her fiancé.

He sat down at his desk and picked up some papers but the words floated before his eyes as his mind went back to Nikki. What had started the breakdown of his marriage? What had gone wrong? What had Nikki called him: a ruthless bastard? She’d been so cool and lucid, that’s what had really shaken him. Thinking about it again he decided that Nikki’s cool and lucid manner had all been a sham. Ruthless bastard? He told himself that women were apt to say absurd things when they were incoherently angry. That helped.

2

East Germany. January 1978.

‘Bring me the mirror,’ said Max Busby. He hadn’t intended that his voice should come out as a croak. Bernard Samson went and got the mirror and placed it on the table so Max could see his arm without twisting inside out. ‘Now take the dressing off,’ said Max.

The sleeve of Max’s filthy old shirt had been torn back as far as the shoulder. Now Bernard unbound the arm, finally peeling back a pad that was caked with pus and dried blood. It was a shock. Bernard gave an involuntary hiss and Max saw the look of horror on his face. ‘Not too bad,’ said Bernard, trying to hide his real feelings.

‘I’ve seen worse,’ said Busby, looking at it and trying to sound unruffled. It was a big wound: deep and inflamed and oozing pus. Bernard had stitched it up with a sewing needle and fishing line from a survival kit but some of his stitches had torn through the soft flesh. The skin around it was mottled every colour of the rainbow and so tender that even to look at it made it hurt more. Bernard was pinching it together tight so it didn’t break right open again. The dressing – an old handkerchief – had got dirty. The side that had been against the wound was dark brown and completely saturated with blood. More blood had crusted in patches all down his arm. ‘It might have been my gun hand.’

Max bent his head until, by the light of the lamp, he could see his pale face in the mirror. He knew about wounds. He knew the way that loss of blood makes the heart pound as it tries to keep supplying oxygen and glucose to the brain. His face had whitened due to the blood vessels contracting as they tried to help the heart do its job. And the heart pumped more furiously as the plasma was lost and the blood thickened. Max tried to take his own pulse. He couldn’t manage it but he knew what he would find: irregular pulse and low body temperature. These were all the signs: bad signs.

‘Put something on the fire and then bind it up tight with the strip of towel. I’ll wrap paper round it before we leave. Don’t want to leave a trail of blood spots.’ He managed a smile. ‘We’ll give them another hour.’ Max Busby was frightened. They were in a mountain hut, it was winter and he was no longer young.

A one-time NYPD cop, he’d come to Europe in 1944, wearing the bars of a US Army lieutenant, and he’d never gone back across the Atlantic except for an attempted reconciliation with his ex-wife in Chicago and a couple of visits to his mother in Atlantic City.

After Bernard had replaced the mirror and put something on to the fire, Max stood up and Bernard helped him with his coat. Then he watched as Max settled down carefully in his chair. Max was badly hurt. Bernard wondered if they would both make it as far as the border.

Max read his thoughts and smiled. Now neither wife nor mother would have recognized Max in his filthy overcoat with battered jeans and the torn shirt under it. There was a certain mad formality to the way that he balanced a greasy trilby hat on his knees. His papers said he was a railway worker but his papers, and a lot of other things he needed, were at the railway station and a Soviet arrest team was there too.

Max Busby was short and squat without being fat. His sparse hair was black and his face was heavily lined. His eyes were reddened by tiredness. He had heavy brows and a large straggly black moustache that was lop-sided because of the way he kept tugging at one end of it.

Older, wiser, wounded and sick, but despite all that and the change in environment and costume, Max Busby did not feel very different to that green policeman who’d patrolled the dark and dangerous Manhattan streets and alleys. Then, as now, he was his own man: the wrongos didn’t all wear black hats. Some of them were to be found spooning their beluga with the police commissioner. It was the same here: no black and white, just shades of grey. Max Busby disdained communism – or ‘socialism’ in the preferred terminology of its practitioners – and all it stood for, with a zeal that was unusual even in the ranks of the men who fought it, but he wasn’t a simplistic crusader.

‘Two hours,’ suggested Bernard Samson. Bernard was big and strong, with wavy hair and spectacles. He wore a scuffed leather zip-front jacket, and baggy corduroy trousers, held up by a wide leather belt decorated with a collection of metal communist Parteitag badges. On his head there was a close-fitting peaked cap of the design forever associated with the ill-fated Afrika Korps. It was a sensible choice of headgear thought Max as he looked at it. A man could go to sleep in a cap like that, or fight without losing it. Max looked at his companion: Bernard was still in one piece, and young enough to wait it out without his nerves fraying and his mouth going dry. Perhaps it would be better to let him go on alone. But would Bernard make it alone? Max was not at all sure he would. ‘They have to get through Schwerin,’ Bernard reminded him. ‘They may be delayed by one of the mobile patrols.’

Max nodded and wet his lips. The loss of blood had sapped his strength: the idea of his contacts being challenged by a Russian army patrol made his stomach heave. Their papers were not good enough to withstand any scrutiny more careful than a cop’s casual flashlight beam. Few false papers are.

He knew that Bernard wouldn’t see the nod, the little room was in darkness except for the faint glimmer from an evil-smelling oil-lamp, its wick turned as low as possible, and from the stove a rosy glow that gave satin toecaps to their boots, but Qui tacet, consentire videtur, silence means consent. Max, like many a NY cop before him, had slaved at night school to study law. Even now he remembered a few basic essentials. More pertinent to his ready consent was the fact that Max knew what it was like to be crossing a hundred and fifty kilometres of moonlit Saxon countryside when there was a triple A alert and a Moscow stop-and-detain order that would absolve any trigger-happy cop or soldier from the consequences of shooting strangers on sight.

Bernard tapped the cylindrical iron stove with his heavy boot and was startled when the door flipped open and red-hot cinders fell out upon the hearth. For a few moments there was a flare of golden light as the draught fed the fire. He could see the wads of brown-edged newspaper packed into the cracks around the door frame and a chipped enamel wash-basin and the rucksacks that had been positioned near the door in case they had to leave in a hurry. And he could see Max as white as a sheet and looking … well, looking like any old man would look who’d lost so much blood and who should be in an intensive-care ward but was trudging across northern Germany in winter. Then it went dull again and the room darkened.

‘Two hours then?’ Bernard asked.

‘I won’t argue.’ Max was carefully chewing the final mouthful of rye bread. It was delicious but he had to chew carefully and swallow it bit by bit. They grew the best rye in the world in Mecklenburg, and made the finest bread with it. But that was the last of it and both men were hungry.

‘That makes a change,’ said Bernard good-naturedly. They seldom truly argued. Max liked the younger man to feel he had a say in what happened. Especially now.

‘I’ll not make an enemy with the guy who’s going to get the German Desk,’ said Max very softly, and twisted one end of his moustache. He tried not to think of his pain.

‘Is that what you think?’

‘Don’t kid around, Bernard. Who else is there?’

‘Dicky Cruyer.’

Max said, ‘Oh, so that’s it. You really resent Dicky, don’t you?’ Bernard always rose to such bait and Max liked to tease him.

‘He could do it.’

‘Well, he hasn’t got a ghost of a chance. He’s too young and too inexperienced. You’re in line; and after this one you’ll get anything you ask for.’

Bernard didn’t reply. It was a welcome thought. He was in his middle thirties and, despite his contempt for desk men, he didn’t want to end up like poor old Max. Max was neither one thing nor the other. He was too old for shooting matches, climbing into other people’s houses and running away from frontier guards, but there was nothing else that he could do. Nothing, that is, that would pay him anything like a living wage. Bernard’s attempts to persuade his father to get Max a job in the training school had been met with spiteful derision. He’d made enemies in all the wrong places. Bernard’s father never got along with him. Poor Max, Bernard admired him immensely, and Bernard had seen Max doing the job as no one else could do it. But heaven only knew how he’d end his days. Yes, a job behind a desk in London would come at exactly the right stage of Bernard’s career.

Neither man spoke for a little while after that. For the last few miles Bernard had been carrying everything. They were both exhausted, and like combat soldiers they had learned never to miss an opportunity for rest. They both dozed into a controlled half sleep. That was all they would allow themselves until they were back across the border and out of danger.

It was about thirty minutes later that the thump thump thump of a helicopter brought them back to wide-eyed awakening. It was a medium-sized chopper, not transport size, and it was flying slowly and at no more than a thousand feet, judging from the sound it made. It all added up to bad news. The German Democratic Republic was not rich enough to supply such expensive gas-guzzling machines for anything but serious business.

‘Shit!’ said Max. ‘The bastards are looking for us.’ Despite the urgency in his voice he spoke quietly, as if the men in the chopper might hear him.

The two men sat in the dark room neither moving nor speaking: they were listening. The tension was almost unbearable as they concentrated. The helicopter was not flying in a straight line and that was an especially bad sign: it meant it had reached its search area. Its course meandered as if it was pin-pointing the neighbouring villages. It was looking for movement: any kind of movement. Outside the snow was deep. When daylight came nothing could move without leaving a conspicuous trail.

In this part of the world, to go outdoors was enough to excite suspicion. There was nowhere to visit after dark, the local residents were simple people, peasants in fact. They didn’t eat the sort of elaborate evening meal that provides an excuse for dinner parties and they had no money for restaurants. As to hotels, who would want to spend even one night here when they had the means to move on?

The sound of the helicopter was abruptly muted as it passed behind the forested hills, and for the time being the night was silent.

‘Let’s get out of here,’ said Max. Such a sudden departure would be going against everything they had planned but Max, even more than Bernard, was a creature of impulse. He had his ‘hunches’. He wrapped folded newspaper round his arm in case the blood came through the towel. Then he put string round the arm of the overcoat and Bernard tied it very tight.

‘Okay.’ Bernard had long ago decided that Max – notwithstanding his inability to find domestic happiness or turn his professional skills into anything resembling a success story – had an uncanny instinct for the approach of danger. Without hesitation and without getting up from his chair, Bernard leaned forward and picked up the big kettle. Opening the stove ring with the metal lifting tool, he poured water into the fire. He did it very carefully and gently, but even so there was a lot of steam.

Max was about to stop him but the kid was right. Better to do it now. At least that lousy chopper was out of sight of the chimney. When the fire was out Bernard put some dead ashes into the stove. It wouldn’t help much if they got here. They’d see the blood on the floorboards, and it would require many gallons of water to cool the stove, but it might make it seem as if they’d left earlier and save them if they had to hide nearby.

‘Let’s go.’ Max took out his pistol. It was a Sauer Model 38, a small automatic dating from the Nazi period, when they were used by high-ranking army officers. It was a lovely gun, obtained by Bernard from some underworld acquaintance in London, where Bernard’s array of shady friends rivalled those he knew in Berlin.