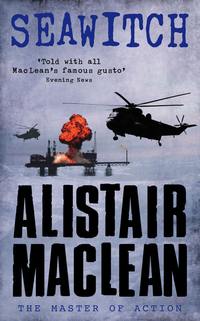

Seawitch

Corral looked depressed. ‘The answer “why not” is easy. By the latest reckoning Lord Worth is one of the world’s five richest men and even two hundred million dollars would only come into the category of pennies as far as he was concerned.’

Mr A looked depressed.

Benson said: ‘Sure, he’d sell.’

Mr A visibly brightened.

‘For two reasons only. In the first place he’d make a quick and splendid profit. In the second place, for less than half the selling price, he could build another Seawitch, anchor it a couple of miles away from the present Seawitch – there are no leasehold rights in extra-territorial waters – and start sending oil ashore at his same old price.’

A temporarily deflated Mr A slumped back in his armchair.

‘A partnership, then,’ Mr A said. His tone was that of a man in a state of quiet despair.

‘Out of the question.’ Henderson was very positive. ‘Like all very rich men, Lord Worth is a born loner. He wouldn’t have a combined partnership with the King of Saudi Arabia and the Shah of Persia even if it had been offered him.’

In a pall-like gloom a baffled and exhausted silence fell upon the embattled ten. A thoroughly bored and hitherto wordless John Cronkite rose.

He said without preamble: ‘My personal fee will be one million dollars. I will require ten million dollars for operating expenses. Every cent of this will be accounted for and the unspent balance returned. I demand a completely free hand and no interference from any of you. If I do encounter any such interference I shall retain the balance of the expenses and at the same time abandon the mission. I refuse to disclose what my plans are – or will be when I have formulated them. Finally, I would prefer to have no further contact with any of you, now or at any time.’

The certainty and confidence of the man were astonishing. Agreement among the mightily-relieved ten was immediate and total. The ten million dollars – a trifling sum to those accustomed to spending as much in bribes every month or so – would be delivered within twenty-four, at the most forty-eight hours to a Cuban numbered account in Miami – the only place in the United States where Swiss-type numbered accounts were permitted. For tax evasion purposes the money, of course, would not come from any of their respective countries; instead, ironically enough, from their bulging offshore funds.

Chapter Two

Lord Worth was tall, lean and erect. His complexion was of the mahogany hue of the playboy millionaire who spends his life in the sun: Lord Worth seldom worked less than sixteen hours a day. His abundant hair and moustache were snow-white. According to his mood and expression and to the eye of the beholder he could have been a Biblical patriarch, a better-class Roman senator or a gentlemanly seventeenth-century pirate – except for the fact, of course, that none of those ever, far less habitually, wore lightweight alpaca suits of the same colour as Lord Worth’s hair.

He looked and was every inch an aristocrat. Unlike the many Americanas who bore the Christian names of Duke or Earl, Lord Worth really was a lord, the fifteenth in succession of a highly distinguished family of Scottish peers of the realm. The fact that their distinction had lain mainly in the fields of assassination, endless clan warfare, the stealing of women and cattle and the selling of their fellow peers down the river was beside the point: the earlier Scottish peers didn’t go in too much for the more cultural activities. The blue blood that had run in their veins ran in Lord Worth’s. As ruthless, predatory, acquisitive and courageous as any of his ancestors, Lord Worth simply went about his business with a degree of refinement and sophistication that would have lain several light years beyond their understanding.

He had reversed the trend of Canadians coming to Britain, making their fortunes and eventually being elevated to the peerage: he had already been a peer, and an extremely wealthy one, before emigrating to Canada. His emigration, which had been discreet and precipitous, had not been entirely voluntary. He had made a fortune in real estate in London before the Internal Revenue had become embarrassingly interested in his activities. Fortunately for him, whatever charges which might have been laid against his door were not extraditable.

He had spent several years in Canada, investing his millions in the Worth Hudson Oil Company and proving himself to be even more able in the oil business than he had been in real estate. His tankers and refineries spanned the globe before he had decided that the climate was too cold for him and moved south to Florida. His splendid mansion was the envy of the many millionaires – of a lesser financial breed, admittedly – who almost literally jostled for elbow-room in the Fort Lauderdale area.

The dining-room in that mansion was something to behold. Monks, by the very nature of their calling, are supposed to be devoid of all earthly lusts, but no monk, past or present, could ever have gazed on the gleaming magnificence of that splendid oaken refectory table without turning pale chartreuse in envy. The chairs, inevitably, were Louis XIV. The splendidly embroidered silken carpet, with a pile deep enough for a fair-sized mouse to take cover in, would have been judged by an expert to come from Damascus and to have cost a fortune: the expert would have been right on both counts. The heavy drapes and embroidered silken walls were of the same pale grey, the latter being enhanced by a series of original Impressionist paintings, no less than three by Matisse and the same number by Renoir. Lord Worth was no dilettante and was clearly trying to make amends for his ancestors’ shortcomings in the cultural fields.

It was in those suitably princely surroundings that Lord Worth was at the moment taking his ease, revelling in his second brandy and the company of the two beings whom after money – he loved most in the world: his two daughters Marina and Melinda, who had been so named by their now divorced Spanish mother. Both were young, both were beautiful, and could have been mistaken for twins, which they weren’t: they were easily distinguishable by the fact that while Marina’s hair was black as a raven’s wing Melinda’s was pure titian.

There were two other guests at the table. Many a local millionaire would have given a fair slice of his ill-gotten gains for the privilege and honour of sitting at Lord Worth’s table. Few were invited, and then but seldom. These two young men, comparatively as poor as church mice, had the unique privilege, without invitation, of coming and going as they pleased, which was pretty often.

Mitchell and Roomer were two pleasant men in their early thirties for whom Lord Worth had a strong if concealed admiration and whom he held in something close to awe – inasmuch as they were the only two completely honest men he had ever met. Not that Lord Worth had ever stepped on the wrong side of the law, although he frequently had a clear view of what happened on the other side: it was simply that he was not in the habit of dealing with honest men. They had both been highly efficient police sergeants, only they had been too efficient, much given to arresting the wrong people such as crooked politicians and equally crooked wealthy businessmen who had previously laboured under the misapprehension that they were above the law. They were fired, not to put too fine a point on it, for their total incorruptibility.

Of the two Michael Mitchell was the taller, the broader and the less good-looking. With slightly craggy face, ruffled dark hair and blue chin, he could never have made it as a matinée idol. John Roomer, with his brown hair and trimmed brown moustache, was altogether better-looking. Both were shrewd, intelligent and highly experienced. Roomer was the intuitive one, Mitchell the one long on action. Apart from being charming both men were astute and highly resourceful. And they were possessed of one other not inconsiderable quality: both were deadly marksmen.

Two years previously they had set up their own private investigative practice, and in that brief space of time had established such a reputation that people in real trouble now made a practice of going to them instead of to the police, a fact that hardly endeared them to the local law. Their homes and combined office were within two miles of Lord Worth’s estate where, as said, they were frequent and welcome visitors. That they did not come for the exclusive pleasure of his company Lord Worth was well aware. Nor, he knew, were they even in the slightest way interested in his money, a fact that Lord Worth found astonishing, as he had never previously encountered anyone who wasn’t thus interested. What they were interested in, and deeply so, were Marina and Melinda.

The door opened and Lord Worth’s butler, Jenkins – English, of course, as were the two footmen – made his usual soundless entrance, approached the head of the table and murmured discreetly in Lord Worth’s ear. Lord Worth nodded and rose.

‘Excuse me, girls, gentlemen. Visitors. I’m sure you can get along together quite well without me.’ He made his way to his study, entered and closed the door behind him, a very special padded door that, when shut, rendered the room completely soundproof.

The study, in its own way – Lord Worth was no sybarite but he liked his creature comforts as well as the next man – was as sumptuous as the dining-room: oak, leather, a wholly unnecessary log fire burning in one corner, all straight from the best English baronial mansions. The walls were lined with thousands of books, many of which Lord Worth had actually read, a fact that must have caused great distress to his illiterate ancestors, who had despised degeneracy above all else.

A tall bronzed man with aquiline features and grey hair rose to his feet. Both men smiled and shook hands warmly.

Lord Worth said: ‘Corral, my dear chap! How very nice to see you again. It’s been quite some time.’

‘My pleasure, Lord Worth. Nothing recently that would have interested you.’

‘But now?’

‘Now is something else again.’

The Corral who stood before Lord Worth was indeed the Corral who, in his capacity as representative of the Florida off-shore leases, had been present at the meeting of ten at Lake Tahoe. Some years had passed since he and Lord Worth had arrived at an amicable and mutually satisfactory agreement. Corral, widely regarded as Lord Worth’s most avowedly determined enemy and certainly the most vociferous of his critics, reported regularly to Lord Worth on the current activities and, more importantly, the projected plans of the major companies, which didn’t hurt Lord Worth at all. Corral, in return, received an annual tax-free retainer of $200,000, which didn’t hurt him very much either.

Lord Worth pressed a bell and within seconds Jenkins entered bearing a silver tray with two large brandies. There was no telepathy involved, just years of experience and a long-established foreknowledge of Lord Worth’s desires. When he left both men sat.

Lord Worth said: ‘Well, what news from the west?’

‘The Cherokee, I regret to say, are after you.’

Lord Worth sighed and said: ‘It had to come some time. Tell me all.’

Corral told him all. He had a near-photographic memory and a gift for concise and accurate reportage. Within five minutes Lord Worth knew all that was worth knowing about the Lake Tahoe meeting.

Lord Worth who, because of the unfortunate misunderstanding that had arisen between himself and Cronkite, knew the latter as well as any and better than most, said at the end of Corral’s report: ‘Did Cronkite subscribe to the ten’s agreement to abjure any form of violence?’

‘No.’

‘Not that it would have mattered if he had. Man’s a total stranger to the truth. And ten million dollars expenses, you tell me?’

‘It did seem a bit excessive.’

‘Can you see a massive outlay like that being concommitant with anything except violence?’

‘No.’

‘Do you think the others believed that there was no connection between them?’

‘Let me put it this way, sir. Any group of people who can convince themselves, or appear to convince themselves, that any action proposed to be taken against you is for the betterment of mankind is also prepared to convince themselves, or appear to convince themselves, that the word “Cronkite” is synonymous with peace on earth.’

‘So their consciences are clear. If Cronkite goes to any excessive lengths in death and destruction to achieve their ends they can always throw up their hands in horror and say, “Good God, we never thought the man would go that far.” Not that any connection between them and Cronkite would ever be established. What a bunch of devious, mealy-mouthed hypocrites!’

He paused for a moment.

‘I suppose Cronkite refused to divulge his plans?’

‘Absolutely. But there is one little and odd circumstance that I’ve kept for the end. Just as we were leaving Cronkite drew two of the ten to one side and spoke to them privately. It would be interesting to know why.’

‘Any chance of finding out?’

‘A fair chance. Nothing guaranteed. But I’m sure Benson could find out – after all, it was Benson who invited us all to Lake Tahoe.’

‘And you think you could persuade Benson to tell you?’

‘A fair chance. Nothing more.’

Lord Worth put on his resigned expression. ‘All right, how much?’

‘Nothing. Money won’t buy Benson.’ Corral shook his head in disbelief. ‘Extraordinary, in this day and age, but Benson is not a mercenary man. But he does owe me the odd favour, one of them being that, without me, he wouldn’t be the president of the oil company that he is now.’ Corral paused. ‘I’m surprised you haven’t asked me the identities of the two men Cronkite took aside.’

‘So am I.’

‘Borosoff of the Soviet Union and Pantos of Venezuela.’ Lord Worth appeared to lapse into a trance. ‘That mean anything to you?’

Lord Worth bestirred himself. ‘Yes. Units of the Russian navy are making a so-called “goodwill tour” of the Caribbean. They are, inevitably, based on Cuba. Of the ten, those are the only two that could bring swift – ah – naval intervention to bear against the Seawitch.’ He shook his head. ‘Diabolical. Utterly diabolical.’

‘My way of thinking too, sir. There’s no knowing. But I’ll check as soon as possible and hope to get results.’

‘And I shall take immediate precautions.’ Both men rose. ‘Corral, we shall have to give serious consideration to the question of increasing this paltry retainer of yours.’

‘We try to be of service, Lord Worth.’

Lord Worth’s private radio room bore more than a passing resemblance to the flight deck of his private 707. The variety of knobs, switches, buttons and dials was bewildering. Lord Worth seemed perfectly at home with them all, and proceeded to make a number of calls.

The first of these were to his four helicopter pilots, instructing them to have his two largest helicopters – never a man to do things by halves, Lord Worth owned no fewer than six of these machines – ready at his own private airfield shortly before dawn. The next four were to people of whose existence his fellow directors were totally unaware. The first was to Cuba, the second to Venezuela. Lord Worth’s world-wide range of contacts – employees, rather – was vast. The instructions to both were simple and explicit. A constant monitoring watch was to be kept on the naval bases in both countries, and any sudden and expected departures of any naval vessels, and their type, was to be reported to him immediately.

The third, to a person who lived not too many miles away, was addressed to a certain Giuseppe Palermo, whose name sounded as if he might be a member of the Mafia, but who definitely wasn’t: the Mafia Palermo despised as a mollycoddling organization which had become so ludicrously gentle in its methods of persuasion as to be in imminent danger of becoming respectable. The next call was to Baton Rouge in Louisiana, where there lived a person who only called himself ‘Conde’ and whose main claim to fame lay in the fact that he was the highest-ranking naval officer to have been court-martialled and dishonourably discharged since World War Two. He, like the others, received very explicit instructions. Not only was Lord Worth a master organizer, but the efficiency he displayed was matched only by his speed in operation.

The noble lord, who would have stoutly maintained – if anyone had the temerity to accuse him, which no one ever had – that he was no criminal, was about to become just that. Even this he would have strongly denied and that on three grounds. The Constitution upheld the rights of every citizen to bear arms; every man had the right to defend himself and his property against criminal attack by whatever means lay to hand; and the only way to fight fire was with fire.

The final call Lord Worth put through, and this time with total confidence, was to his tried and trusted lieutenant, Commander Larsen.

Commander Larsen was the captain of the Seawitch.

Larsen – no one knew why he called himself ‘Commander’, and he wasn’t the kind of person you asked – was a rather different breed of man from his employer. Except in a public court or in the presence of a law officer he would cheerfully admit to anyone that he was both a non-gentleman and a criminal. And he certainly bore no resemblance to any aristocrat, alive or dead. But for all that there did exist a genuine rapport and mutual respect between Lord Worth and himself. In all likelihood they were simply brothers under the skin.

As a criminal and non-aristocrat – and casting no aspersions on honest unfortunates who may resemble him – he certainly looked the part. He had the general build and appearance of the more viciously daunting heavy-weight wrestler, deep-set black eyes that peered out under the overhanging foliage of hugely bushy eyebrows, an equally bushy black beard, a hooked nose and a face that looked as if it had been in regular contact with a series of heavy objects. No one, with the possible exception of Lord Worth, knew who he was, what he had been or from where he had come. His voice, when he spoke, came as a positive shock: beneath that Neanderthaloid façade was the voice and the mind of an educated man. It really ought not to have come as such a shock: beneath the façade of many an exquisite fop lies the mind of a retarded fourth-grader.

Larsen was in the radio room at that moment, listening attentively, nodding from time to time, then flicked a switch that put the incoming call on to the loudspeaker.

He said: ‘All clear, sir. Everything understood. We’ll make the preparations. But haven’t you overlooked something, sir?’

‘Overlooked what?’ Lord Worth’s voice over the telephone carried the overtones of a man who couldn’t possibly have overlooked anything.

‘You’ve suggested that armed surface vessels may be used against us. If they’re prepared to go to such lengths isn’t it feasible that they’ll go to any lengths?’

‘Get to the point, man.’

‘The point is that it’s easy enough to keep an eye on a couple of naval bases. But I suggest it’s a bit more difficult to keep an eye on a dozen, maybe two dozen airfields.’

‘Good God!’ There was a long pause during which the rattle of cogs and the meshing of gear-wheels in Lord Worth’s brain couldn’t be heard. ‘Do you really think –’

‘If I were on the Seawitch, Lord Worth, it would be six and half a dozen to me whether I was clobbered by shells or bombs. And planes could get away from the scene of the crime a damn sight faster than ships. They could get clean away. The US navy or land-based bombers would have a good chance of intercepting surface vessels. And another thing, Lord Worth.’

There was a moment’s pause.

‘A ship could stop at a distance of a hundred miles. No distance at all for the guided missile, I believe they have a range of four thousand miles these days. When the missile was, say, twenty miles from us, they could switch on its heat-source tracking device. God knows, we’re the only heat-source for a hundred miles around.’

Another lengthy pause, then: ‘Any more encouraging thoughts occur to you, Commander Larsen?’

‘Yes, sir. Just one. If I were the enemy – I may call them the enemy –’

‘Call the devils what you want.’

‘If I were the enemy I’d use a submarine. They don’t even have to break water to loose off a missile. Poof! No Seawitch. No signs of any attacker. Could well be put down to a massive explosion aboard the Seawitch. Far from impossible, sir.’

‘You’ll be telling me next that there’ll be atomic-headed missiles.’

‘To be picked up by a dozen seismological stations? I should think it hardly likely, sir. But that may just be wishful thinking. I have no wish to be vaporized.’

‘I’ll see you in the morning.’ The line went dead.

Larsen hung up his phone and smiled widely. One would have subconsciously imagined this action to reveal a set of yellowed fangs: instead, it revealed a perfect set of gleamingly white teeth. He turned to look at Scoffield, his head driller and right-hand man.

Scoffield was a large, rubicund, smiling man, the easy-going essence of good nature. To the fact that this was not precisely the case any member of his drilling crews would have eagerly and blasphemously testified. Scoffield was a very tough citizen indeed and one could assume that it was not innate modesty that made him conceal this: much more probably it was a permanent stricture of the facial muscles caused by the four long vertical scars on his cheeks, two on either side. Clearly he, like Larsen, was no great advocate of plastic surgery. He looked at Larsen with understandable curiosity.

‘What was all that about?’

‘The day of reckoning is at hand. Prepare to meet thy doom. More specifically, his lordship is beset by enemies.’ Larsen outlined Lord Worth’s plight. ‘He’s sending what sounds like a battalion of hard men out here in the early morning, accompanied by suitable weaponry. Then in the afternoon we are to expect a boat of some sort, loaded with even heavier weaponry.’

‘One wonders where he’s getting all those hard men and weaponry from.’

‘One wonders. One does not ask.’

‘All this talk – your talk – about bombers and submarines and missiles. Do you believe that?’

‘No. It’s just that it’s hard to pass up the opportunity to ruffle the aristocratic plumage.’ He paused then said thoughtfully: ‘At least I hope I don’t believe it. Come, let us examine our defences.’

‘You’ve got a pistol. I’ve got a pistol. That’s defences?’

‘Well, where we’ll mount the defences when they arrive. Fixed large-bore guns, I should imagine.’

‘If they arrive.’

‘Give the devil his due. Lord Worth delivers.’

‘From his own private armoury, I suppose.’

‘It wouldn’t surprise me.’

‘What do you really think, Commander?’

‘I don’t know. All I know is that if Lord Worth is even half-way right life aboard may become slightly less monotonous in the next few days.’

The two men moved out into the gathering dusk on to the platform. The Seawitch was moored in 150 fathoms of water – 900 feet – which was well within the tensioning cables’ capacities – safely south of the US’s mineral leasing blocks and the great east-west fairway, straight on top of the biggest oil reservoir yet discovered round the shores of the Gulf of Mexico. The two men paused at the drilling derrick where a drill, at its maximum angled capacity, was trying to determine the extent of the oilfield. The crew looked at them without any particular affection but not with hostility. There was reason for the lack of warmth.

Before any laws were passed making such drilling illegal, Lord Worth wanted to scrape the bottom of this gigantic barrel of oil. Not that he was particularly worried, for government agencies are notoriously slow to act: but there was always the possibility that they might bestir themselves this time and that, horror of horrors, the bonanza might turn out to be vastly larger than estimated.