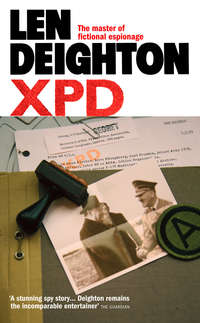

XPD

‘There is something he could do for us in California,’ said the DG.

‘Oh, daddy. You don’t know how wonderful that would be. Not just for me,’ she added hastily. ‘But for Boyd too. You know how much he hates it in the office.’

The DG knew exactly how much Boyd Stuart hated it in the office. His son-in-law had frequently used dinner invitations to acquaint him with his preference for a reassignment overseas. The DG had done nothing about it, deciding that it would look very bad if he interceded for a close relative.

‘It’s quite urgent too,’ said the DG. ‘We’d have to get him away by the weekend at the latest.’

Jennifer kissed her father. ‘You are a darling,’ she said. ‘Boyd knows California. He did an exchange year at UCLA.’

Boyd Stuart was a handsome, dark-complexioned man whose appearance – like his excellent German and Polish and fluent Hungarian – enabled him to pass himself off as an inhabitant of anywhere in that region vaguely referred to as central Europe. Stuart had been born of a Scottish father and Polish mother in a wartime internment camp for civilians in the Rhineland. After the war, Stuart had attended schools in Germany, Scotland and Switzerland by the time he went to Cambridge. It was there that his high marks and his athletic and linguistic talents brought him under the scrutiny of the British intelligence recruiters.

‘You say there is no file, Sir Sydney?’ Stuart had not had a personal encounter with his father-in-law since that unforgettable night when he had the dreadful quarrel with Jennifer. Sir Sydney Ryden had arrived at four o’clock in the morning and taken her back to live with her parents again.

Stuart was wearing rather baggy, grey flannel trousers and a blue blazer with one brass button missing. It was not exactly what he would have chosen to wear for this encounter but there was nothing he could do now about that. He realized that the DG was similarly unenthusiastic about the casual clothes, and found himself tugging at the cotton strands remaining from his lost button.

‘That is a matter of deliberate policy,’ said the DG. ‘I cannot overemphasize how delicate this business is.’ The DG gave one of his mirthless smiles. This mannerism – mere baring of the teeth – was some atavistic warning not to tread further into sacred territory. The DG stared down into his whisky and then suddenly finished it. He was given to these abrupt movements and long periods of stillness. Ryden was well over six feet tall and preferred to wear black suits which, with his lined, pale face and luxuriant, flowing hair, made him look like a poet from some Victorian romance. He would need little more than a long black cloak to go on stage as Count Dracula, thought Stuart, and wondered if the DG deliberately contrived this forbidding appearance.

Without preamble, the DG told Stuart the story again, shortening it this time to the essential elements. ‘On 8 April 1945, elements of the 90th Division of the United States Third Army under General Patton were deep into Germany. When they got to the little town of Merkers, in western Thuringia, they seat infantry into the Kaiseroda salt mine. Those soldiers searched through some thirty miles of galleries in the mine. They found a newly installed steel door. When they broke through it they discovered gold; four-fifths of the Nazi gold reserves were stored there. So were two million or more of the rarest of rare books from the Berlin libraries, the complete Goethe collection from Weimar, and paintings and prints from all over Europe. It would take half an hour or more to read through the list of material. I’ll let you have a copy.’

Stuart nodded but didn’t speak. It was late afternoon and sunlight made patterns on the carpet, moving across the room until the bright bars slimmed to fine rods and one by one disappeared. The DG went across to the bookcases to switch on the large table lamps. On the panelled walls there were paintings of horses which had won famous races a long time ago, but now the paintings had grown so dark under the ageing varnish that the strutting horses seemed to be plodding home through a veil of fog.

‘Just how much gold was four-fifths of the German gold reserves?’ Stuart asked.

The DG sniffed and ran a finger across his ear, pushing away an errant lock of hair. ‘About three hundred million dollars’ worth of gold is one estimate. Over eight thousand bars of gold.’ The DG paused. ‘But that was just the bullion. In addition there were three thousand four hundred and thirty-six bags of gold coins, many of which were rarities – coins worth many times their weight in gold because of their value to collectors.’

Stuart looked up and, realizing that some response was expected, said, ‘Yes, amazing, sir.’ He sipped some more of the whisky. It was always the best of malts up here in the DG’s office at the top of ‘the Ziggurat’, the curious, truncated, pyramidal building that looked across the River Thames to the Palace of Westminster. The room’s panelling, paintings and antique furniture were all part of an attempt to recapture the elegance that the Secret Intelligence Service had enjoyed in the beautiful old houses in St James’s. But this building was steel and concrete, cheap and practical, with rust stains dribbling on the façade and cracks in the basement. The service itself could be similarly described.

‘The American officers reported their find through the usual channels,’ said the DG, suddenly resuming his story. ‘Patton and Eisenhower went to see it on 12 April. The army moved it all to Frankfurt. They took jeeps and trailers down the mine and brought it out. Ingenious people, the Americans, Stuart.’ He smiled and held the smile while looking Stuart full in the eyes.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘It took about forty-eight hours of continuous work to load the valuables. There were thirty crates of German patent-office records – worth a king’s ransom – and two thousand boxes of prints, drawings and engravings, as well as one hundred and forty rolls of oriental carpets. You see the difficulties, Stuart?’

‘Indeed I do, sir.’ He swirled the last of his drink round his glass before swallowing it. The DG gave no sign of noticing that his glass was empty.

‘They were ordered to begin loading the lorries just two days after Eisenhower’s visit. The only way to do that was simply by listing whatever was on the original German inventory tags. It was a system that had grave shortcomings.’

‘If things were stolen, there was no way to be sure that the German inventory had been correct in the first place?’

The DG nodded. ‘Can you imagine the chaos that Germany was in by that stage of the war?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Quite so, Stuart. You can not imagine it. God knows what difficulties the Germans had moving all their valuables in those days of collapse. But I assure you that the temptation for individual Germans to risk all in order to put some items in their pockets could never have been higher. Perhaps only the Germans could have moved such material intact in those circumstances. As a nation they have a self-discipline that one can only admire.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘As soon as the Americans captured the mine, its contents went by road to Frankfurt, and were stored in the Reichsbank building. A special team from the State Department were given commissions overnight, put into uniform and flown from Washington to Frankfurt. They sifted that material to find sensitive papers or secret diplomatic exchanges that would be valuable to the US government, or embarrassing to them if made public. After that it was all turned over to the Inter-Allied Reparations Agency.’

‘And was there such secret material?’

‘Let me get you another drink, Stuart. You like this malt, don’t you? With water this time?’

‘Straight please, sir.’

The DG gave another of his ferocious grins.

‘Of course there was secret material. The exchanges between the German ambassador in London and his masters in Berlin during the 1930s would have caused a few red faces here in Whitehall, to say nothing of red faces in the Palace of Westminster. Enough indiscretions there to have put a few of our politicians behind bars in 1940 … members of Parliament telling German embassy people what a splendid fellow Adolf Hitler was.’

The DG poured drinks for them both. He used fresh cut-glass tumblers. ‘Something wrong with that door, Stuart?’

‘No, it’s beautiful,’ said Stuart, admiring the antique panelling. ‘And the octagonal oak table must be early seventeenth century.’

The DG groaned silently. It was not the sort of remark expected of the right sort of chap. Ryden had been brought up to believe that a gentleman did not make specific references to another man’s possessions. He had always suspected that Boyd Stuart might be ‘artistic’ – a word the DG used to describe a wide variety of individuals that he blackballed at his club and shunned socially. ‘No ice? No soda? Nothing at all in it?’ asked the DG again, but he marred the solicitude by descending into his seat as he said it.

Stuart shook his head and raised the heavy tumbler to his lips.

‘No,’ agreed the DG. ‘With a fine Scots name such as Boyd Stuart a man must not be seen watering a Highland malt.’

‘Not in front of a Sassenach,’ said Stuart.

‘What’s that? Oh yes, I see,’ said the DG raising a hand to his hair. Stuart realized that his father-in-law wore his hair long to hide the hearing aid. It was a surprising vanity in such a composed figure; Stuart noted it with interest. ‘Oxford, Stuart?’

Stuart looked at him for a moment before answering. A man who could commit to memory all the details of the Kaiseroda mine discoveries was not likely to forget where his son-in-law went to university. ‘Cambridge, sir. Trinity. I read mathematics.’

The DG closed his eyes. It was quite alarming the sort of people the department had recruited. They would be taking sociologists next. He was reminded of a joke he had heard at his club at lunch. A civil service candidate made an official complaint: he had missed promotion because at the civil service selection board he had admitted to being a socialist. The commissioner had apologized profoundly – or so the story went – he had thought the candidate had admitted to being a sociologist.

Boyd Stuart sipped his whisky. He did not strongly dislike his father-in-law – he was a decent enough old buffer in his way. If Ryden idolized his daughter so much that he could not see her faults, that was a very human failing.

‘Was it Jennifer’s idea?’ Stuart asked him. ‘Sending me to California, was that her idea?’

‘We wanted someone who knew something about the film trade,’ said Sir Sydney. ‘You came to mind immediately …’

‘You mean, had it been banking, backgammon or the Brigade of Guards,’ said Stuart, ‘I might have been trampled in the rush.’

The DG smiled to acknowledge the joke. ‘I remembered that you studied at the UCLA.’

‘But it was Jennifer’s idea?’

The DG hesitated rather than tell a deliberate untruth. ‘Jennifer feels it would be better … in the circumstances.’

Stuart smiled. He could recognize the machinations of his wife.

‘Little thought you’d find yourself in this business when you were at Trinity, eh Stuart?’ said the DG, determined to change the subject.

‘To tell you the absolute truth, sir, I was hoping to be a tennis professional.’

The DG almost spluttered. He had a terrible feeling that this operation was going to be his Waterloo. He would hate to retire with a notable failure on his hands. His wife had set her mind on his getting a peerage. She had even been exploring some titles; Lord and Lady Rockhampton was her current favourite. It was the town in Australia in which her father had been born. Sir Sydney had promised to find out if this title was already taken by someone. He rather hoped it was.

‘Yes, a fascinating game, tennis,’ said the DG. My God. And this was the man who would have to be told about the ‘Hitler Minutes’, the most dangerous secret of the war. This was the fellow who would be guarding Winston Churchill’s reputation.

‘The convoy of lorries left Merkers to drive to Frankfurt on 15 April 1945,’ said the DG, continuing his story. ‘We think three, or even four, lorries disappeared en route to Frankfurt. None of the valuables and the secret documents on them were ever recovered. The US army never officially admitted the loss of the lorries but unofficially they said three.’

‘And you think that this film company in California now have possession of the documents?’

The DG went to the window, looking at the cactus plants that were lined up to get the maximum benefit from the light. He picked one pot up to examine it closely. ‘I can assure you quite categorically, Stuart, that we are talking about forgeries. We are talking about mythology.’ He sat down, still holding the plant pot and touching the soil carefully.

‘It’s something that would embarrass the government?’

The DG sniffed. He wondered how long it would take to get his message across. ‘Yes, Stuart, it is.’ He put the cactus on the coffee table and picked up his drink.

‘Are we going to try to prevent this company from making a film about the Kaiseroda mine and its treasures?’ Stuart asked.

‘I don’t give a tinker’s curse about the film,’ said the DG. He patted his hair nervously. ‘But I want to know what documentation he has access to.’ He drank some of his whisky and glanced at the skeleton clock on the mantelpiece. He had another meeting after this and he was running short of time.

‘I’m not sure I know exactly what I’m looking for,’ Stuart said.

The DG stood up. It was Stuart’s cue to depart. In the half-light, his lined face underlit by the table lamp, and his huge, dark-suited figure silhouetted against the dying sun, Ryden looked satanic. ‘You’ll know it when you see it. We’ll keep in contact with you through our controllers in California. Good luck, my boy.’

‘Thank you, sir.’ Stuart rose too.

‘You’ve seen Operations? Got all the procedures settled? You understand about the money – it’s being wired to the First Los Angeles Bank in Century City.’ The DG smiled. ‘Jennifer tells me you are giving her lunch tomorrow.’

‘There are some things she wants from the flat,’ explained Stuart.

‘Get to California as soon as possible, Stuart.’

‘There are just a few personal matters to settle,’ said Stuart. ‘Cancel my holiday arrangements and stop the milk.’

The DG looked at the clock again. ‘We have people in the department who will attend to the details, Stuart. We can’t have operations delayed because of a few bottles of milk.’

Chapter 4

‘We have people in the department who will attend to the details, Stuart,’ said Boyd Stuart in a comical imitation of the DG’s voice.

Kitty King, Boyd Stuart’s current girlfriend, giggled and held him closer. ‘So what did you say, darling?’

‘Not this gorgeous little detail they won’t, I told him. Some things must remain sacred.’ He patted her bottom.

‘You fool! What did you really say?’

‘I opened my mouth and poured his whisky into it. By the time I’d finished it, he’d disappeared through the floor, like the demon king in the pantomime.’ He kissed her again. ‘I’m going to Los Angeles.’

She wriggled loose from his grasp. ‘I know all about that,’ she said. ‘Who do you think typed your orders this afternoon?’ She was the secretary to the deputy chief of Operations (Region Three).

‘Will you be faithful to me while I’m away?’ said Stuart, only half in fun.

‘I’ll wash my hair every night, and go early to bed with Keats and hot cocoa.’

It was an unlikely promise. Kitty was a young busty blonde who attracted men, young and old, as surely as picnics bring wasps. She looked up, saw the look on Stuart’s face and gave him a kiss on the end of his nose. ‘I’m a child of the sexual revolution, Boyd darling. You must have read about it in Playboy?’

‘I never read Playboy; I just look at the pictures. Let’s go to bed.’

‘I’ve made you that roasted eggplant dip you like.’ Kitty King was a staunch vegetarian; worse, she was an evangelistic one. Amazing, someone at the office had remarked after seeing her in a bikini, to think that it’s all fruit and nuts. ‘You like that, don’t you.’

‘Let’s go to bed,’ said Stuart.

‘I must turn off the oven first, or my chickpea casserole will dry up completely.’

She backed away from him slowly. In spite of the disparity in their ages, she found him disconcertingly attractive. Until now her experiences with men had been entirely under her control but Boyd Stuart, in spite of all his anxious remarks, kept her in her place. She was surprised and annoyed to discover that she rather liked the new sort of relationship.

She looked at him and he smiled. He was a handsome man: the wide, lined face and the mouth that turned down at one side could suddenly be transformed by a devastating smile, and his laugh was infectious.

‘Your chickpea casserole!’ said Boyd Stuart. ‘We don’t want that to dry up, darling.’ He laughed a loud, booming laugh and she could not resist joining in. He put out his hand to her. She noticed that the back of it was covered with small scars and the thumb joint was twisted. She had asked him about it once but he had made some joke in reply. There was always a barrier; these men who had worked in the field were all the same in this respect. There was no way in which to get to know them completely. There was always a ‘no entry’ sign. Always some part of their brain was on guard and awake. And Kitty King was enough of a woman to want her man to be completely hers.

Boyd Stuart pushed open the door of the bedroom. It was the best room in the apartment in many ways: large and light, like so many of these rambling Victorian houses near the river on the unfashionable side of Victoria Station. That was why he had a writing desk in a window space of his bedroom, a corner which Kitty King liked to refer to grandiosely as ‘the study’.

‘Kitty!’ he called.

She came into the bedroom, leaned back against the door and smiled as the latch clicked.

‘Kitty. The lock of my desk is broken.’ He opened the inlaid walnut front of the antique bureau. The lock had been torn away from the wood and there were deep scratches in the polished surface. ‘You didn’t break into it, did you, Kitty?’

‘Of course not, Boyd. I’m not interested in your old love letters.’

‘It’s not funny, Kitty. I have classified material in here.’ Already he was sifting through the drawers and pigeonholes. He found the airline ticket, his passport, the letter to the bank, a couple of contact addresses and an old photo of a man named Bernard Lustig cut from a film trade magazine. There was also a newspaper cutting that he had been given by the department.

An all-expenses-paid trip to the movie capital of the world and the luxury of the exclusive Beverly Hills Hotel.

Veterans of the US Third Army and attached units who were concerned with the movement of material from the Kaiseroda salt mine, Merkers, Thuringia, Germany, in the final days of the Second World War are urgently sought by B. Lustig Productions Inc. The corporation is preparing a major motion picture about this historical episode. Veterans should send full details, care of this newspaper, to Box 2188. Photos and documents will be treated with utmost care and returned to the sender by registered post.

Kitty King watched him search through the items.

‘Nothing seems to have been taken,’ said Stuart. ‘Did you leave the door open when you went down to the dustbin?’

‘There was no one on the stairs,’ she said.

‘Waiting upstairs,’ said Stuart. ‘The same kid who did the burglaries in the other flats, I’ll bet.’

‘Are you going to phone the department?’

‘Nothing’s missing. And the front door has no signs of forced entry.’

‘The papers for your trip were there, weren’t they?’

He nodded.

‘Then you must have known about going last Sunday – when you put the tickets and things in there.’ There was a note of resentment in her voice.

‘I still wasn’t sure until I saw the DG late this afternoon.’

‘I wish you’d discussed it with me, Boyd.’ He looked up sharply. This was a new side of Kitty King. She had always described their relationship as no more than a temporary ‘shack-up’. She was a career woman, she had always maintained, with a good degree in political science from the London School of Economics, and the aim of becoming a Permanent Secretary, the top of the Administrative Class grades.

Stuart said, ‘If I phone the night duty officer, they’ll be all over us. You know what a fuss they’ll make. We’ll be up all night writing reports.’

‘You know best, sweetheart.’

‘A kid probably, looking for cash. When he found only this sort of thing he got out quickly, before you came back upstairs again.’

‘Does your wife still have her key to this place?’ Kitty asked.

‘She wouldn’t break open my desk.’

‘That’s not what I asked you.’

‘It was just some kid looking for cash. Nothing is missing. Stop worrying about it.’

‘She’d like to get you back, Boyd. You realize that, don’t you?’

Boyd put his arms round her tightly and kissed her for a long time.

Chapter 5

The Steins – father and son – lived in a large house in Hollywood. Cresta Ridge Drive provides a sudden and welcome relief from the exhaust fumes and noise of Franklin Avenue. It is one of a tangle of steep winding roads that lead into the Hollywood hills and end at Griffith Park and Lake Hollywood. Its elevation gives the house a view across the city, and on smoggy days when the pale tide of pollution engulfs the city, the sky here remains blue.

By Californian standards these houses are old, discreetly sited behind mature horse-chestnut trees now grown up to the roofs. In the thirties some of them, their gardens blazing with hibiscus and bougainvillea as they were this day, had been owned by film stars. Even today long-lost but strangely familiar faces can be glimpsed at the check-out of the Safeway or self-serving gasoline at Wilbur’s. But most of Stein’s neighbours were corporate lawyers, ambitious dentists and refugees from the nearby aerospace communities.

On this afternoon a rainstorm deluged the city. It was as if nature was having one last fling before the summer.

Outside the Steins’ house there was a white Imperial Le Baron two-door hardtop, one of the biggest cars in the Chrysler range. The paintwork shone in the hard, unnatural light that comes with a storm, and the heavy rain glazed the paintwork and the dark tinted windows. Sitting – head well down – in the back seat was a man. He appeared to be asleep but he was not even dozing.

The car’s owner – Miles MacIver – was inside the Stein home. Stein senior was not at home, and now his son Billy was regretting the courtesy he had shown in inviting MacIver into the house.

MacIver was a well-preserved man in his late fifties. His white hair emphasized the blue eyes with which he fixed Billy as he talked. He smiled lazily and used his large hands to emphasize his words as he strode restlessly about the lounge. Sometimes he stroked his white moustache, or ran a finger along an eyebrow. They were the gestures of a man to whom appearance was important: an actor, a womanizer or a salesman. MacIver possessed attributes of all three.

It was a large room, comfortably furnished with good quality furniture and expensive carpets. MacIver’s restless prowling was proprietorial. He went to the Bechstein grand piano, its top crowded with framed photographs. From the photos of friends and relatives, MacIver selected a picture of Charles Stein, the man he had come to visit, taken at the training battalion at Camp Edwards, Massachusetts, sometime in the early 1940s. Stein was dressed in the uncomfortable, ill-fitting coveralls which, like the improvised vehicle behind him, were a part of America’s hurried preparations for war. Stein leaned close to one side of the frame, his arm seemingly raised as if to embrace it.