The Beechwood Airship Interviews

There was me – I wasn’t filming, I was directing – and there were three guys with cameras and an actor whose name I cannot remember … Graham? He was a proper actor and he was dressed as a City gent, you know – suit, overcoat, briefcase – and the idea was that he would come out of Farringdon tube station and walk through Smithfield and then down Giltspur Street – I’d mapped all this thing out and written a screenplay and everything!

He would be possessed by the spirit of the bull and become like the Minotaur almost, and descend into a type of madness. So we were filming him walking along, walking faster and faster and looking behind him and then, outside the Old Bailey, he stood against a wall, freaking out, and then start throwing his clothes off and chucking his briefcase!

‘We were filming all this on the hoof and because we just had little handy-cams people couldn’t tell that he was being filmed, you know?

We got down to the River Thames and the City of London Police came and stopped us. Apparently they’d been filming us with CCTV all the way down, filming us making a film – except they didn’t know we were making a film, they had no idea what was going on. Thankfully this was before all the terrorism stuff, otherwise I don’t know what would have happened. The police wanted to confiscate all the cameras and I had to say, “Right, no. You’re not confiscating anything, we’ve stopped,” and then we just filmed the last bit where the Minotaur gent walks into the Thames. Just about managed to get away with it.

Then the film got made but I lost it! (Laughs)

It’s one of those things. No one’s ever seen it.

I guess all that became R&D for the Amnesiac book. Funny how all that condenses down into such a little anecdote.’

• • • • •

I want to ask you about the thing underneath Kid A.

(I take the Kid A CD from my bag and begin to take apart the case)

‘Oh, the thing underneath!?’*

Yes, the hidden thing underneath!

‘That was the record after OK Computer, yes* – I hate jewel cases, as I’ve said, and I took one to bits and was looking at it and I realised there was this tiny gap and thought, “You could put something in there …”

They had to hand-pack them, apparently – it couldn’t be done by a machine. So I think that annoyed the record label … again.

That was really tough, that record; really tough for everyone. It was forced out, really.’

You took a lot of people with you, though, with Kid A and what followed.

‘Not a purposeful thing.’

What do you remember of that time?

‘The time? Um, I kind of … I don’t really remember it in the same way I remember childhood or something. I think it was over the course of about two years but In Rainbows was about two years and that was bliss compared to that.

I was not very happy, I don’t think.

OK Computer had been so successful, everything a band could want – number one record, good reviews, lots of sales, blahdy blah … I think they were worried about turning into U2 or something. You know, doing another OK Computer and turning into a huge, Simple Minds-esque stadium rock band – the weight of success hung extremely heavy.’

For you as well? Did you feel that?

‘Um, no. No, because I was even more anonymous then than I am now but … (thinks for a minute) I really can’t remember it too well – it was just fucking hard.

(Brightening) I’m very proud of it. In fact, it’s difficult to choose my favourite but I think, because it was such hard work, I think that was a really good one – and I really liked the music as well, that was when I really connected with them, musically, although that started with OK Computer.’

What was it about OK Computer?

‘I remember Thom screaming in an outhouse … they were recording out in this stately home, the first stately home of many, and he was screaming in a shed in the middle of nowhere with a mic and a line running all the way from that little shed, all the way into this impromptu recording studio; I thought, “That’s it.”’

Do you work with a sense of ‘I need to make an album cover’?

‘No, I don’t really. With all the albums I’ve done, the cover has been the very last thing – usually, almost a snap decision. The cover for Hail to the Thief was a big painting, a metre and a half square, and it was hanging up in the studio and it was not even going to be a part of the record artwork. It was the first one I did in that style and size and, because it hadn’t got words from the record on it, it was sort of outside of it all.

We were just sitting down and saying, “Which one should we put on the cover?”

“Why don’t we use that one?”

And suddenly it was obvious that it was the cover. The same with Kid A. The night before we had to decide I did loads and loads of printouts and stuck them round the kitchen with tape. There were loads of different titles as well. Loads of different titles. And we had them all up. Stuck onto all the cupboards in the kitchen. “Okay, there’s a cover in the kitchen somewhere, you’ve gotta find it.” (Laughs)

And luckily they chose that one and, I mean, this is my memory, but I think partly the title was because it looked so brilliant in that typeface – BD Plakatbau.

We had other titles with different typefaces.’

You seem to strive to avoid a recognisable style with your work.

‘Yes, I wouldn’t want to do the same thing twice anyway. I think that would be boring.

Someone like Vaughan Oliver, who did all the sleeves for 4AD* – Cocteau Twins, Pixies – and they were all different but they were all his, and I’ve always wanted to work in a way where you couldn’t tell it was the same person doing it.

I had a fantastic compliment with In Rainbows when someone said, “Oh, did you do that?” Which was great! It’s so totally unlike what I’ve done before; all abstract … and lovely in its way. Pretty. I became very interested in velocity – ink and velocity, paint and velocity and what happens when you throw or squirt pigment at a surface. I was squirting stuff out of needles and I found them quite frightening to use, needles, they’re very spiky … and this was a direct response to the music after that strict architectural drawing, and what happened was that I was working in this decaying stately home and I knocked over a candle and it poured a load of molten wax onto a piece of paper and I was really taken with this, and it was at the same time I was working with these needles so I began to work with these ideas of spurting and dripping and melting which seemed to fit very much, for me, with what the music was. I found that record an extremely sexual record, very sensual.’

They’d been threatening it for years.

‘Exactly. (Deadpan) It’s the long-awaited happy album.’

It was pretty chipper.

‘Yeah! Molten wax, squirting stuff out of needles, spattering …’

It’s all there, for goodness sake! It’s all there!

‘There it is!’ (Laughter)

So is the new thing always the most exciting thing?

‘Yes. To do the same thing you’ve done before … why would you do it again?

There’s no point in repeating yourself. I mean, in a way, what I’ve been doing recently with Hartmann the Anarchist* is repeating myself. I’ve done that, but I haven’t illustrated a book before and I love a bit of lino, I do. I love the physicality of carving it out, but I don’t want to do the same artwork I’ve done before … it’s easy to draw the same picture you’ve drawn before.

If I tried to draw an OK Computer-style picture now it would be really easy; and I could do it better than before, you know, “better” in inverted commas but … it’s horrible to look back on stuff. It gets easier after a while, when it becomes history.’

The recent past isn’t any good?

‘No. There’s a difference between memory and history, isn’t there – the difference between, “Oh yeah, I was just doing that a little while ago, I remember that … oh God!” and when it becomes history and you can look at it in a more even way. I can look back at most of my stuff when it’s got into its history phase and quite like it. It’s alright … but maybe that’s to do with working in this periodic way with capsules and projects because of the Radiohead thing. “Here’s the record – Phoosh!” It’s clearly delineated between one record and the next.’

Do you think you’d work like that if you didn’t work with the band?

‘No idea. I’ve been working with them since I was twenty … four? And I’m forty now … but, you know, I’ll still wake up at night and think, “I should be doing this” or “I should be doing that” or “What can I do to make that better?” I don’t like it. I’d rather not have that happen.

I always feel envious of people who have a job and when they get home they don’t think about their job any more, but maybe that doesn’t exist. I always felt envious when I was cycling back from college, seeing people in their cars driving back to their homes on a housing estate somewhere – driving their car which looks the same as everyone else’s car, parking it in front of a house that looks like everyone else’s house but somehow they know it’s theirs … they’d park their car and they’d open the door and they’d close the door of their car, “Ker-chumph”, and open the door of their house, “Kru-ch-ch”, and in they’d go in and that would be it … but I’ve always sort of known that …’

Not for you?

‘Well, it’s not been possible for me to be able to hate my job! (Laughs) That’s the thing; people hate their jobs. I don’t hate my job, I quite like it. I hate it sometimes but it could be worse, oh yes!’

• • • • •

It’s late now and the dance hall beyond the office is dark. We take a break from talking for the tape and I go off to find the toilet. My Dictaphone records cars passing and the creaking of the building and Stanley pottering about with tea and wine. It records the moment he accidentally spills wine over my notebook and then, to compensate, closes it to leave a Tyrian butterfly over my notes. After a long procession of echoey footsteps I re-enter the room, unaware of the mishap. Stanley doesn’t mention the turn of events and I don’t discover it until I get home.

• • • • •

Old Bond Street, Bath

Saturday 12 March 2011

I bump into Stanley in a stationers and he invites me to the pub. He is working on something big, he says, biggest thing he’s ever done. The project’s tentacles spread worldwide … but he can’t tell me anything about it. It’s all set up and in place, though. Ready to go at the press of a button.

Yes, it’s to do with the band.

It’ll all kick off soon, yes.

He’ll explain more in a bit when he’s allowed.

We drink up and he cycles off.

Brick Lane, London

Monday 28 March 2011

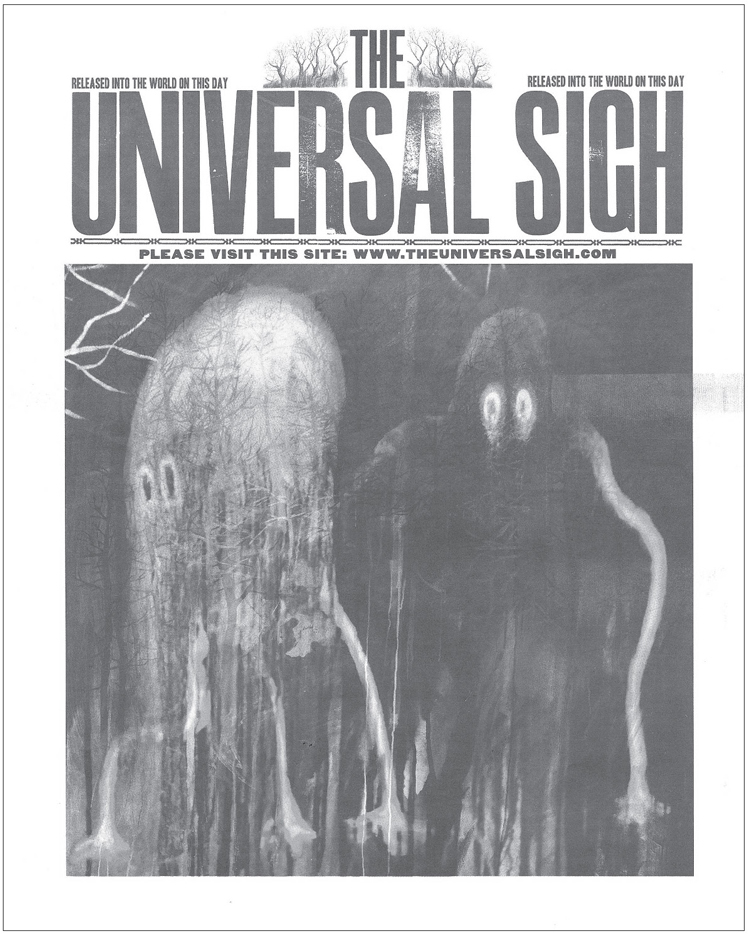

So, The King of Limbs,* a Radiohead album, has been put out into the world digitally with a ‘newspaper album’ to follow, whatever that is. Very mysterious.

The artwork features colourful paintings of trees fronting dark woods beyond, strange multi-limbed creatures and lurking, vaguely glimpsed monsters.

I’m in Brick Lane, in a long queue of people that snakes back several hundred metres from a Rough Trade record shop.

Stanley has made a concomitant newspaper that is to be given away at noon today around the world, apparently. All the noons.

Information is somewhat scarce yet here we all are in the queue, and there’s a buzz; something’s up.

A strange website has appeared with directions to this place and a warning reminiscent of the fire escape instructions above Stanley’s studio window:

IMPORTANT NOTICE:

This newspaper IS NOT the newspaper that accompanies the Newspaper Album version of The King of Limbs.

This event WILL NOT be repeated. This event IS NOT a live performance by Radiohead.

I am here to experience the physical, tactile event of being given a newspaper and leafing through it to see what I can see … I imagine Stanley will be still cycling around Devon or somewhere and the last I heard the band were in LA so it’s a bit odd to turn the corner and find him and Thom Yorke dressed up as barrow boys in flat caps and braces, proffering copies of The Universal Sigh* newspaper.

‘Socialist Worker!’

‘Sooo-cialist Worker!?’

‘Socialist Worker, sir?’

• • • • •

Derelict dance hall, Bath

July 2011

The last time I saw you was just before the Socialist Worker debacle.

‘Oh yes … I was a bit scared because I didn’t know where it was happening. I got to Liverpool Street and then walked round and round the queue. I felt like a hyena circling a herd of wildebeest. It was a good day!

It was the most orderly and polite London mob I’ve ever experienced.

There was quite a lot of fuss and I was very pleased because we had this big meeting before we began with all the record company people who were to act like this big distribution network for the paper, and the publicity plan was to give out a newspaper in sixty-one cities around the world, simultaneously, for free, that mentioned neither the band nor the title of the album once. They took a little persuading but I think it worked. It got into every real newspaper. It was sufficiently stupid to even catch the eye of the Sun:

‘“Read all about it,” says Yorke, miserablist.

‘“Professional Gloom-monger Thom Yorke was today spotted in London’s Brick Lane handing out an incomprehensible art project …”

‘And then I went home and then I had a cup of tea and thought, “That was alright! I can begin to forget all about it.” Which I almost have.

It was fun though. We both wore flat caps and everything.’

Was The King of Limbs newspaper album designed around the same time as the Universal Sigh?

‘No, that was from the year before; September or something, and it went through lots of redesigns. Imagine setting up a newspaper and publishing the first issue, all that tweaking, changing … because there were going to be loads of sections and a little A5 magazine; lots of different sections, one black, white and red like an old-fashioned tabloid …’

We spoke about these things obliquely before, I suppose, down the pub.

‘Yeah, though it’s weird; when I was doing all the King of Limbs stuff it was all I was thinking about, but now it’s quite hard to recall … but I just thought it was really nice how the newspaper album turned out and the prints were quite rough, with mistakes and holes punched – so valueless, you know? So ephemeral. If you want to keep it nice you’ve got quite a job on your hands.’

Keeping it out of the sunshine … because it’s on the way out already.

‘Exactly. Self-destructing record packaging. I won’t get a Grammy for that one, I’ll tell you now. (Laughs) They won’t appreciate such irreverence, the Grammers.’

I see you’re cutting some wavy lino in the other room.

‘Yeah, meteors or fireballs, Vorticist waves; it’s taken a long time … it’s not just waves, you know! They’re the easy bit, they’re like a little treat for me after doing all the buildings. I did the downtown financial district and all these modernist blocks and they’re really boring to do, but the nicer stuff takes a long time so it’s a bit of a trade-off really.’

Is this for Atoms For Peace?*

‘Yes. I hope so. It is at the moment.’

A lot of your Radiohead work seems cloak and dagger. You’re wrapped up in these projects but can’t discuss them.

‘Yeah, I know, it is weird – very internal, all of us very locked in. I didn’t over-listen to this record either. I mean, I listened to it, obviously, I couldn’t avoid hearing it a lot, but I wanted to try and keep it as something I could enjoy later rather than being sick to death of it – because I usually get really enthusiastic and listen to it intensely, which is great for the year or so it takes to do the artwork but after that … no.

I’ve recently just about been able to listen to OK Computer. I really over-listened to that.’

How does that situation arise? Do you put it on?

‘In shops? It makes me slightly uncomfortable for some reason when I hear Radiohead music in shops. I don’t know why. I don’t know … because in my head it’s still quite a secretive thing and then you think, “Oh no! Everybody knows!”’

Where does this bunker mentality come from, do you think? I mean, other bands are able to embrace it.

‘I know! Able to “Live The Dream!” We’re congenitally unable to live the dream. That’s it. That’s what everybody wants to do, don’t they?

I don’t know what the secrecy thing is about really … perhaps it gets out of hand.’

It’s a bit late now, perhaps, on album number fifteen.

‘Is it!?’

Not really, no. (Laughter)

‘No, it’s about eight or something … I’m supposed to be getting the lino stuff finished because that’s supposed to be being exhibited around the time the Atoms For Peace record comes out.’

Can you tell me that? Surely that’s supposed to be shrouded in subterfuge.

‘I can’t live the dream!’

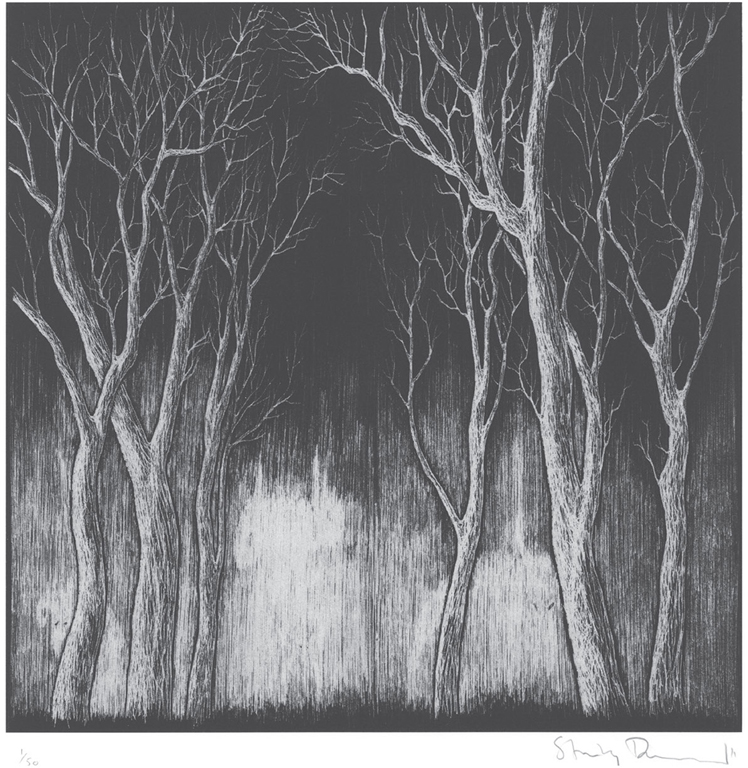

A while ago you mentioned painting a series of portraits in oil. What became of them?

‘They ended up being the trees for King of Limbs! I was going to paint naturalistic portraits of the band because I looked at Gerhard Richter’s paintings and they were really good and I thought, “I’ll do that,” but, of course, I’m not Gerhard Richter; I couldn’t do that. It was not possible. Where he managed to get all these great blurred effects in oil paint, mine turned into mud, it was awful; very depressing for about three months … and then I started painting trees in oils in Oxford … and it all came about because of the way cathedrals used to be all different colours inside. Apparently all the vaults and tracery used to be painted really bright colours before the Puritans came along and painted over them white. All Northern European ecclesiastical architecture is based on the forest – being in glades, being in a sacred grove – they would paint their cathedrals in the brightest colours they’d got, absolutely beautiful. Going into a cathedral would have been like entering into an illuminated manuscript forest and I just thought, if all the trees of the forest were all different colours, how beautiful it would be … and that’s how King of Limbs came to be.

There you are, a rare moment of articulacy! You should put it in a special box with red arrows pointing to it.’

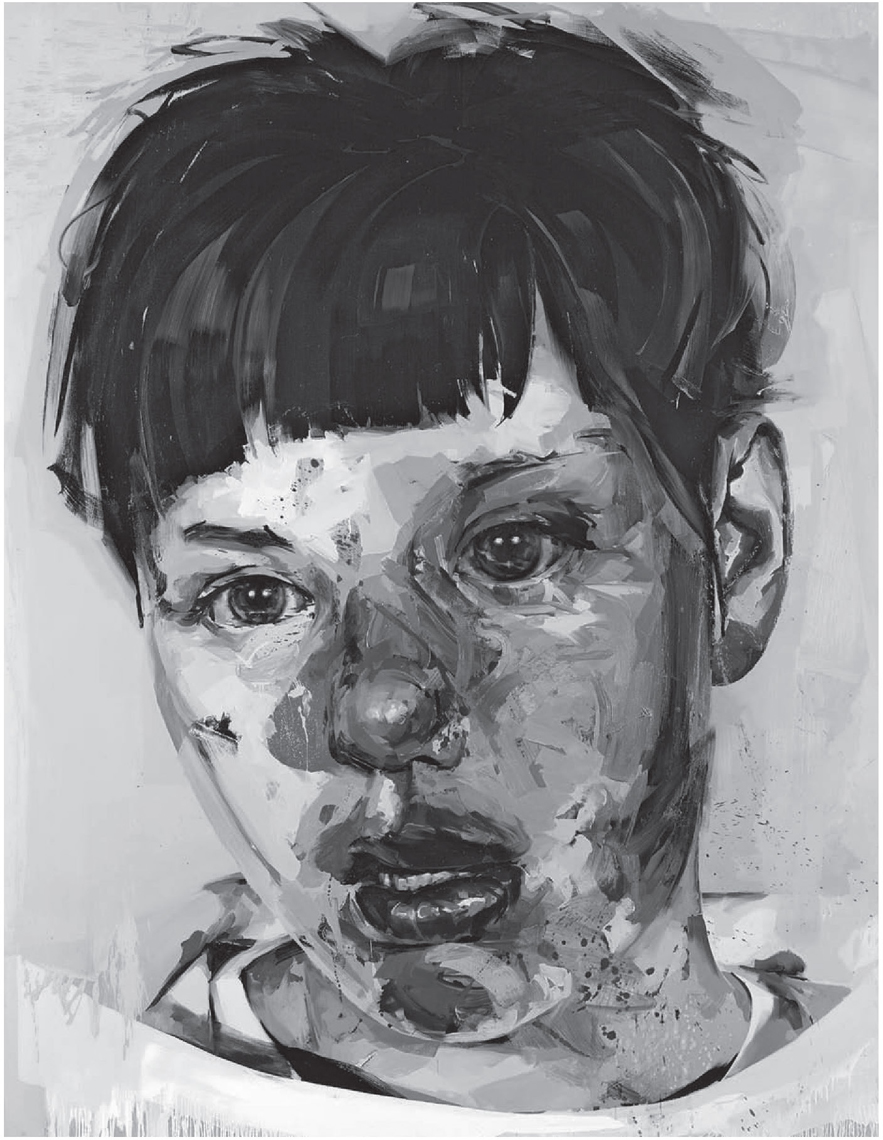

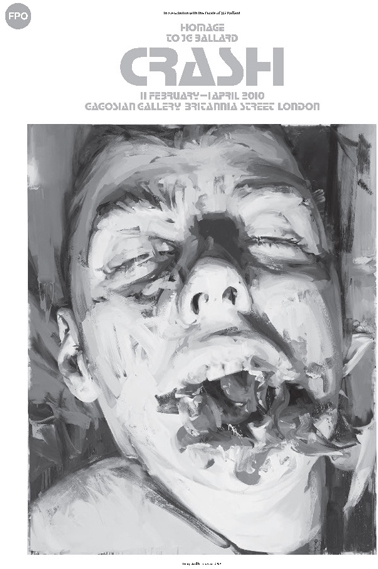

JENNY SAVILLE, RA (1970– ) is a Cambridge-born artist. Her visceral oil paintings and drawings of the human body are often realised on a massive scale and have appeared in exhibitions at the Royal Academy of Art, Gagosian Galleries and Norton Museum of Art, Florida. Her work has featured on the covers of two albums by Manic Street Preachers – The Holy Bible (1994) and Journal for Plague Lovers (2009).

JENNY SAVILLE

Brewer Street, Oxford

26 January 2010

In light of Stanley’s eclecticism, I wrote to Gagosian, Jenny Saville’s gallery, and asked if I might have an audience with her since she seemed to represent the other end of the spectrum: a lone figure singularly preoccupied with painting flesh and the figure – solid, tangible, massive adipose studies of the body in oils.

The last I’d read, she was working in Sicily, so the approach was a bit of a punt since I wasn’t sure how I’d get out there even if she agreed to see me. However, it turned out Jenny had recently relocated to a studio in Oxford, so any thoughts of a Mediterranean adventure were quickly replaced with the more prosaic reality of a day return ticket because, to my surprise, she did agree to see me.

So one freezing Tuesday morning – satchel packed with a wine-stained notebook and a fickle Dictaphone – I caught a train.*

• • • • •

Jenny Saville’s studio is in a quiet shaded lane that belies its central city location. A two-storey building; grey-fronted and anonymous.

Lewis Carroll wrote Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland at Christ Church College, two minutes from here. My rabbit hole is rather unprepossessing – an ashen door with a burnt-out intercom. I clatter at the letterbox and wait, stamping my feet in the cold.

Descending footsteps. Jenny opens the door and I step in. To my left is a room of large, briefly glimpsed drawings and charcoal pieces.

A set of stairs before me. We go up and Jenny makes tea.

The first floor is spacious and open plan, lit by large windows and greenhouse-like skylights. The walls are white. In front of the walls are paintings.

At the top of the stairs is a three-metre-high work of a newborn baby, the umbilical cord snaking back to a splayed vagina and soapy legs. Along from this is a trolley stand stacked with books – magazines, newspaper paint swatches, photographs and journals. Notes, clippings and articles are stuck up on the walls while other torn-out pages are filed out on the floor – creative ‘compost’ as Francis Bacon dubbed it.*

Empty cigarette packets, turned to display pictures of cancer and disease – bad teeth, laryngeal tumours, black lungs – are lined up on a dado rail.

Below the packets is a radiator that bears a painterly impression of Jenny’s bottom – a Rorschach test pattern.

The studio, as well as being large, is freezing and Jenny explains she can only work for an hour or so before she starts to seize up. The radiator is where she warms herself and takes stock:

‘This is where I stand, as you can see. I find that a cigarette is a perfect space to stand or sit and analyse what you’re doing – the length of a cigarette.’

Opposite the radiator are several explorations of a single subject – a face with a mangled mouth; eyes closed, taut waxen skin lit from below, rising from a writhing, exploded mess. There are three versions of this piece, a large charcoal drawing, a mostly monochrome painted scheme – some patches of intense red and peach/pine – and an enormous black and white painting, streaked and leaking, the running paint visible below the surface layer.

None of the three is explicit about what is going on with the mouth, the wound is elusive and seemingly out of focus – a flayed moment of abstract expressionism – a de Kooning maw.

The finished piece, Witness, has recently left the studio for a London show in honour of J.G. Ballard. I’ve just missed it:

‘I think that show’s a brilliant thing to do because he was going to write my catalogue notes several times and I’ve got a lot of faxed letters from him – these great rejection letters from Ballard. (Laughs) Whenever I was asked who I’d like to write the catalogue I would always say, “Ballard. J.G. Ballard,” but first his partner was ill and then he was ill and then he wrote a fantastic summary of my work but didn’t want to write the catalogue – I’ve still got that. Everyone I’ve told about it has said, “Oh, you’ve got to publish it” – letters from Shepperton. I’ve got a really good interview with him that I taped off the radio. It’s from just after he wrote Cocaine Nights and he’s talking about the internet. Claire Walsh, his partner, was telling me how they used to watch a site where you can see the migration of swallows, a camera follows them. That was his favourite thing to watch.’*

We sit down on a pair of paint-specked chairs and I ask about the studio, how long she’s been here, and the differences between here and her previous workspace in Palermo, Sicily.

‘In Palermo I had the guts of animals outside my studio window; the stench was amazing in the summer. That has an effect on the way you think about making work. When I first walked in here there was blossom on the trees and it had an airy feeling. I haven’t wanted to overload it so far, it’s quite pure for me to have a space like this with only the work and a few things up – normally the floor is a cascade of books, but they’re all still in boxes so I’ve quite enjoyed having a clearer head. I’ve noticed that, when I have a lot of reference material around, I tend to work a certain way, so I’ve tried to switch that around a bit and see what happens.’