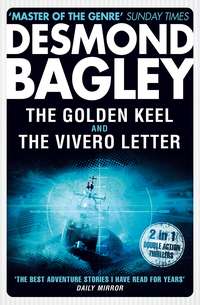

The Golden Keel / The Vivero Letter

The wheelhouse – which Krupke called the ‘deckhouse’ – was well fitted. There were two echo sounders, one with a recording pen. Engine control was directly under the helmsman’s hand and the windows in front were fitted with Kent screens for bad weather. There was a big marine radio transceiver – and there was radar.

I put my hand on the radar display and said, ‘What range does this have?’

‘It’s got several ranges,’ he said. ‘You pick the one that’s best at the time. I’ll show you.’

He snapped a switch and turned a knob. After a few seconds the screen lit up and I could see a tiny plan of the harbour as the scanner revolved. Even Sanford was visible as one splotch among many.

‘That’s for close work,’ said Krupke, and turned a knob with a click. ‘This is maximum range – fifteen miles, but you won’t see much while we’re in harbour.’

The landward side of the screen was now too cluttered to be of any use, but to seaward, I saw a tiny speck. ‘What’s that?’

He looked at his watch. ‘That must be the ferry from Gibraltar. It’s ten miles away – you can see the mileage marked on the grid.’

I said, ‘This gadget must be handy for making a landfall at night.’

‘Sure,’ he said. ‘All you have to do is to match the screen profile with the chart. Doesn’t matter if there’s no moon or if there’s a fog.’

I wished I could have a set like that on Sanford but it’s difficult installing radar on a sailing vessel – there are too many lines to catch in the antenna. Anyway, we wouldn’t have the power to run it.

I looked around the wheelhouse. ‘With all this gear you can’t need much of a crew, even though she is a biggish boat,’ I said. ‘What crew do you have?’

‘Me and Metcalfe can run it ourselves,’ said Krupke. ‘Our trips aren’t too long. But usually we have another man with us – that Moroccan you’ve got on Sanford.’

I stayed aboard the Fairmile for a long time, but Metcalfe and Walker didn’t show up, so after a while I went back to Metcalfe’s flat. Coertze was already there, but there was no sign of the others, so we went to have dinner as a twosome.

Over dinner I said, ‘We ought to be getting away soon. Everything is fixed at this end and we’d be wasting time if we stayed any longer.’

‘Ja,’ Coertze agreed. ‘This isn’t a pleasure trip.’

We went back to the flat and found it empty, apart from the servants. Coertze went to his room and I read desultorily from a magazine. About ten o’clock I heard someone coming in and I looked up.

I was immediately boiling with fury.

Walker was drunk – blind, paralytic drunk. He was clutching on to Metcalfe and sagging at the knees, his face slack and his bleared eyes wavering unseeingly about him. Metcalfe was a little under the weather himself, but not too drunk. He gave Walker a hitch to prevent him from falling, and said cheerily, ‘We went to have a night on the town, but friend Walker couldn’t take it. You’d better help me dump him on his bed.’

I helped Metcalfe support Walker to his room and we laid him on his bed. Coertze, dozing in the other bed, woke up and said, ‘What’s happening?’

Metcalfe said, ‘Your pal’s got no head for liquor. He passed out on me.’

Coertze looked at Walker, then at me, his black eyebrows drawing angrily over his eyes. I made a sign for him to keep quiet.

Metcalfe stretched and said, ‘Well, I think I’ll turn in myself.’ He looked at Walker and there was an edge of contempt to his voice. ‘He’ll be all right in the morning, barring a hell of a hangover. I’ll tell Ismail to make him a prairie oyster for breakfast.’ He turned to Coertze. ‘What do you call it in Afrikaans?’

‘’n Regmaker,’ Coertze growled.

Metcalfe laughed. ‘That’s right. A Regmaker. That was the first word I ever learned in Afrikaans.’ He went to the door. ‘See you in the morning,’ he said, and was gone.

I closed the door. ‘The damn fool,’ I said feelingly.

Coertze got out of bed and grabbed hold of Walker, shaking him. ‘Walker,’ he shouted. ‘Did you tell him anything?’

Walker’s head flapped sideways and he began to snore. I took Coertze’s shoulder. ‘Be quiet; you’ll tell the whole household,’ I said. ‘It’s no use, anyway; you won’t get any sense out of him tonight – he’s unconscious. Leave it till morning.’

Coertze shook off my hand and turned. He had a black anger in him. ‘I told you,’ he said in a suppressed voice. ‘I told you he was no good. Who knows what the dronkie said?’

I took off Walker’s shoes and covered him with a blanket. ‘We’ll find out tomorrow,’ I said. ‘And I mean we. Don’t you go off pop at him, you’ll scare the liver out of him and he’ll close up tight.’

‘I’ll donner him up,’ said Coertze grimly. ‘That’s God’s truth.’

‘You’ll leave him alone,’ I said sharply. ‘We may be in enough trouble without fighting among ourselves. We need Walker.’

Coertze snorted.

I said, ‘Walker has done a job here that neither of us could have done. He has a talent for acting the damn’ fool in a believable manner.’ I looked down at him, then said bitterly, ‘It’s a pity he can be a damn’ fool without the acting. Anyway, we may need him again, so you leave him alone. We’ll both talk to him tomorrow, together.’

Coertze grudgingly gave his assent and I went to my room.

VI

I was up early next morning, but not as early as Metcalfe, who had already gone out. I went in to see Walker and found that Coertze was up and half dressed. Walker lay on his bed, snoring. I took a glass of water and poured it over his head. I was in no mood to consider Walker’s feelings.

He stirred and moaned and opened his eyes just as Coertze seized the carafe and emptied it over him. He sat up spluttering, then sagged back. ‘My head,’ he said, and put his hands to his temples.

Coertze seized him by the front of the shirt. ‘Jou gogga-mannetjie, what did you say to Metcalfe?’ He shook Walker violently. ‘What did you tell him?’

This treatment was doing Walker’s aching head no good, so I said, ‘Take it easy; I’ll talk to him.’

Coertze let go and I stood over Walker, waiting until he had recovered his wits. Then I said, ‘You got drunk last night, you stupid fool, and of all people to get drunk with you had to pick Metcalfe.’

Walker looked up, the pain of his monumental hangover filming his eyes. I sat on the bed. ‘Now, did you tell him anything about the gold?’

‘No,’ cried Walker. ‘No, I didn’t.’

I said evenly, ‘Don’t tell us any lies, because if we catch you out in a lie you know what we’ll do to you.’

He shot a frightened glance at Coertze who was glowering in the background and closed his eyes. ‘I can’t remember,’ he said. ‘It’s blank; I can’t remember.’

That was better; he was probably telling the truth now. The total blackout is a symptom of alcoholism. I thought about it for a while and came to the conclusion that even if Walker hadn’t told Metcalfe about the gold he had probably blown his cover sky high. Under the influence, the character he had built up would have been irrevocably smashed and he would have reverted to his alcoholic and unpleasant self.

Metcalfe was sharp – he wouldn’t have survived in his nefarious career otherwise. The change in character of Walker would be the tip-off that there was something odd about old pal Halloran and his crew. That would be enough for Metcalfe to check further. We would have to work on the assumption that Metcalfe would consider us worthy of further study.

I said, ‘What’s done is done,’ and looked at Walker. His eyes were downcast and his fingers were nervously scrabbling at the edge of the blanket.

‘Look at me,’ I said, and his eyes rose slowly to meet mine. ‘I think you’re telling the truth,’ I said coldly. ‘But if I catch you in a lie it will be the worse for you. And if you take another drink on this trip I’ll break your back. You think you’re scared of Coertze here; but you’ll have more reason to be scared of me if you take just one more drink. Understand?’

He nodded.

‘I don’t care how much you drink once this thing is finished. You’ll probably drink yourself to death in six months, but that’s got nothing to do with me. But just one more drink on this trip and you’re a dead man.’

He flinched and I turned to Coertze. ‘Now, leave him alone; he’ll behave.’

Coertze said, ‘Just let me get at him. Just once,’ he pleaded.

‘It’s finished,’ I said impatiently. ‘We have to decide what to do next. Get your things packed – we’re moving out.’

‘What about Metcalfe?’

‘I’ll tell him we want to see some festival in Spain.’

‘What festival?’

‘How do I know which festival? There’s always some goddam festival going on in Spain; I’ll pick the most convenient. We sail this afternoon as soon as I can get harbour clearance.’

‘I still think I could do something about Metcalfe,’ said Coertze meditatively.

‘Leave Metcalfe alone,’ I said. ‘He may not suspect anything at all, but if you try to beat him up then he’ll know there’s something fishy. We don’t want to tangle with Metcalfe if we can avoid it. He’s bigger than we are.’

We packed our bags and went to the boat, Walker very quiet and trailing in the rear. Moulay Idriss was squatting on the foredeck smoking a kif cigarette. We went below and started to stow our gear.

I had just pulled out the chart which covered the Straits of Gibraltar in preparation for planning our course when Coertze came aft and said in a low voice, ‘I think someone’s been searching the boat.’

‘What the hell!’ I said. Metcalfe had left very early that morning – he would have had plenty of time to give Sanford a good going over. ‘The furnaces?’ I said.

We had disguised the three furnaces as well as we could. The carbon clamps had been taken off and scattered in tool boxes in the forecastle where they would look just like any other junk that accumulates over a period. The main boxes with the heavy transformers were distributed about Sanford, one cemented under the cabin sole, another disguised as a receiving set complete with the appropriate knobs and dials, and the third built into a marine battery in the engine space.

It is doubtful if Metcalfe would know what they were if he saw them, but the fact that they were masquerading in innocence would make him wonder a lot. It would be a certain clue that we were up to no good.

A check over the boat showed that everything was in order. Apart from the furnaces, and the spare graphite mats which lined the interior of the double coach roof, there was nothing on board to distinguish us from any other cruising yacht in these waters.

I said, ‘Perhaps the Moroccan has been doing some exploring on his own account.’

Coertze swore. ‘If he’s been poking his nose in where it isn’t wanted I’ll throw him overboard.’

I went on deck. The Moroccan was still squatting on the foredeck. I said interrogatively, ‘Mr Metcalfe?’

He stretched an arm and pointed across the harbour to the Fairmile. I put the dinghy over the side and rowed across. Metcalfe hailed me as I got close. ‘How’s Walker?’

‘Feeling sorry for himself,’ I said, as Metcalfe took the painter. ‘A pity it happened; he’ll probably be as sick as a dog when we get under way.’

‘You leaving?’ said Metcalfe in surprise.

I said, ‘I didn’t get the chance to tell you last night. We’re heading for Spain.’ I gave him my prepared story, then said, ‘I don’t know if we’ll be coming back this way. Walker will, of course, but Coertze and I might go back to South Africa by way of the east coast.’ I thought that there was nothing like confusing the issue.

‘I’m sorry about that,’ said Metcalfe. ‘I was going to ask you to design a dinghy for me while you were here.’

‘Tell you what,’ I said. ‘I’ll write to Cape Town and get the yard to send you a Falcon kit. It’s on me; all you’ve got to do is pay for the shipping.’

‘Well, thanks,’ said Metcalfe. ‘That’s decent of you.’ He seemed pleased.

‘It’s as much as I can do after all the hospitality we’ve had here,’ I said.

He stuck out his hand and I took it. ‘Best of luck, Hal, in all your travels. I hope your project is successful.’

I was incautious. ‘What project?’ I asked sharply.

‘Why, the boatyard you’re planning. You don’t have anything else in mind, do you?’

I cursed myself and smiled weakly. ‘No, of course not.’ I turned to get into the dinghy, and Metcalfe said quietly, ‘You’re not cut out for my kind of life, Hal. Don’t try it if you’re thinking of it. It’s tough and there’s too much competition.’

As I rowed back to Sanford I wondered if that was a veiled warning that he was on to our scheme. Metcalfe was an honest man by his rather dim lights and wouldn’t willingly cut down a friend. But he would if the friend didn’t get out of his way.

At three that afternoon we cleared Tangier harbour and I set course for Gibraltar. We were on our way, but we had left too many mistakes behind us.

FOUR: FRANCESCA

When we were beating through the Straits Coertze suggested that we should head straight for Italy. I said, ‘Look, we’ve told Metcalfe we were going to Spain, so that’s where we are going.’

He thumped the cockpit coaming. ‘But we haven’t time.’

‘We’ve got to make time,’ I said doggedly. ‘I told you there would be snags which would use up our month’s grace; this is one of the snags. We’re going to take a month getting to Italy instead of a fortnight, which cuts us down to two weeks in hand – but we’ve got to do it. Maybe we can make it up in Italy.’

He grumbled at that, saying I was unreasonably frightened of Metcalfe. I said, ‘You’ve waited fifteen years for this opportunity – you can afford to wait another fortnight. We’re going to Gibraltar, to Malaga and Barcelona; we’re going to the Riviera, to Nice and to Monte Carlo; after that, Italy. We’re going to watch bullfights and gamble in casinos and do everything that every other tourist does. We’re going to be the most innocent people that Metcalfe ever laid eyes on.’

‘But Metcalfe’s back in Tangier.’

I smiled thinly. ‘He’s probably in Spain right now. He could have passed us any time in that Fairmile of his. He could even have flown or taken the ferry to Gibraltar, dammit. I think he’ll keep an eye on us if he reckons we’re up to something.’

‘Damn Walker,’ burst out Coertze.

‘Agreed,’ I said. ‘But that’s water under the bridge.’

I was adding up the mistakes we had made. Number one was Walker’s incautious statement to Aristide that he had drawn money on a letter of credit. That was a lie – a needless one, too – I had the letter of credit and Walker could have said so. Keeping control of the finances of the expedition was the only way I had of making sure that Coertze didn’t get the jump on me. I still didn’t know the location of the gold.

Now, Aristide would naturally make inquiries among his fellow bankers about the financial status of this rich Mr Walker. He would get the information quite easily – all bankers hang together and the hell with ethics – and he would find that Mr Walker had not drawn any money from any bank in Tangier. He might not be too perturbed about that, but he might ask Metcalfe about it, and Metcalfe would find it another item to add to his list of suspicions. He would pump Aristide to find that Walker and Halloran had taken an undue interest in the flow of gold in and out of Tangier.

He would go out to the Casa Saeta and sniff around. He would find nothing there to conflict with Walker’s cover story, but it would be precisely the cover story that he suspected most – Walker having blown hell out of it when he was drunk. The mention of gold would set his ears a-prick – a man like Metcalfe would react very quickly to the smell of gold – and if I were Metcalfe I would take great interest in the movements of the cruising yacht, Sanford.

All this was predicated on the fact that Walker had not told about the gold when he was drunk. If he had, then the balloon had really gone up.

We put into Gibraltar and spent a day rubber-necking at the Barbary apes and looking at the man-made caves. Then we sailed for Malaga and heard a damn’ sight more flamenco music than we could stomach.

It was on the second day in Malaga, when Walker and I went out to the gipsy caves like good tourists, that I realized we were being watched. We were bumping into a sallow young man with a moustache everywhere we went. He sat far removed when we ate in a sidewalk café, he appeared in the yacht basin, he applauded the flamenco dancers when we went to see the gipsies.

I said nothing to the others, but it only went to confirm my estimate of Metcalfe’s abilities. He would have friends in every Mediterranean port, and it wouldn’t be difficult to pass the word around. A yacht’s movements are not easy to disguise, and he was probably sitting in Tangier like a spider in the centre of a web, receiving phone calls from wherever we went. He would know all our movements and our expenditure to the last peseta.

The only thing to do was to act the innocent and hope that we could wear him out, string him on long enough so that he would conclude that his suspicions were unfounded, after all.

In Barcelona we went to a bullfight – the three of us. That was after I had had a little fun in trying to spot Metcalfe’s man. He wasn’t difficult to find if you were looking for him and turned out to be a tall, lantern-jawed cut-throat who carried out the same routine as the man in Malaga.

I was reasonably sure that if anyone was going to burgle Sanford it would be one of Metcalfe’s friends. The word would have been passed round that we were his meat and so the lesser fry would leave us alone. I hired a watchman who looked as though he would sell his grandmother for ten pesetas and we all went to the bullfight.

Before I left I was careful to set the stage. I had made a lot of phoney notes concerning the costs of setting up a boatyard in Spain, together with a lot of technical stuff I had picked up. I also left a rough itinerary of our future movements as far as Greece and a list of addresses of people to be visited. I then measured to a millimetre the position in which each paper was lying.

When we got back the watchman said that all had been quiet, so I paid him off and he went away. But the papers had been moved, so the locked cabin had been successfully burgled in spite of – or probably because of – the watchman. I wondered how much he had been paid – and I wondered if my plant had satisfied Metcalfe that we were wandering innocents.

From Barcelona we struck out across the Gulf of Lions to Nice, giving Majorca a miss because time was getting short. Again I went about my business of visiting boatyards and again I spotted the watcher, but this time I made a mistake.

I told Coertze.

He boiled over. ‘Why didn’t you tell me before?’ he demanded.

‘What was the point?’ I said. ‘We can’t do anything about it.’

‘Can’t we?’ he said darkly, and fell into silence.

Nothing much happened in Nice. It’s a pleasant place if you haven’t urgent business elsewhere, but we stayed just long enough to make our cover real and then we sailed the few miles to Monte Carlo, which again is a nice town for the visiting tourist.

In Monte Carlo I stayed aboard Sanford in the evening while Coertze and Walker went ashore. There was not much to do in the way of maintenance beyond the usual housekeeping jobs, so I relaxed in the cockpit enjoying the quietness of the night. The others stayed out late and when they came back Walker was unusually silent.

Coertze had gone below when I said to Walker, ‘What’s the matter? The cat got your tongue? How did you like Monte?’

He jerked his head at the companionway. ‘He clobbered someone.’

I went cold. ‘Who?’

‘A chap was following us all afternoon. Coertze spotted him and said that he’d deal with it. We let this bloke follow us until it got dark and then Coertze led him into an alley and beat him up.’

I got up and went below. Coertze was in the galley bathing swollen knuckles. I said, ‘So you’ve done it at last. You must use your goddamn fists and not your brains. You’re worse than Walker; at least you can say he’s a sick man.’

Coertze looked at me in surprise. ‘What’s the matter?’

‘I hear you hit someone.’

Coertze looked at his fist and grinned at me. ‘He’ll never bother us again – he’ll be in hospital for a month.’ He said this with pride, for God’s sake.

‘You’ve blown it,’ I said tightly. ‘I’d just about got Metcalfe to the point where he must have been convinced that we were O.K. Now you’ve beaten up one of his men, so he knows we are on to him, and he knows we must be hiding something. You might just as well have phoned him up and said, “We’ve got some gold coming up; come and take it from us.” You’re a damn’ fool.’

His face darkened. ‘No one can talk to me like that.’ He raised his fist.

‘I am talking to you like that,’ I said. ‘And if you lay one finger on me you can kiss the gold goodbye. You can’t sail this or any other boat worth a damn, and Walker won’t help you – he hates your guts. You hit me and you’re out for good. I know you could probably break me in two and you’re welcome to try, but it’ll cost you a cool half-million for the pleasure.’

This showdown had been coming for a long time.

He hesitated uncertainly. ‘You damned Englishman,’ he said.

‘Go ahead – hit me,’ I said, and got ready to take his rush.

He relaxed and pointed his finger at me threateningly. ‘You wait until this is over,’ he said. ‘Just you wait – we’ll sort it out then.’

‘All right, we’ll sort it out then,’ I said. ‘But until then I’m the boss. Understand?’

His face darkened again. ‘No one bosses me,’ he blustered.

‘Right,’ I said. ‘Then we start going back the way we came – Nice, Barcelona, Malaga, Gibraltar. Walker will help me sail the boat, but we won’t do a damn’ thing for you.’ I turned away.

‘Wait a minute,’ said Coertze and I turned back. ‘All right,’ he said hoarsely. ‘But wait till this is over; by God, you’ll have to watch yourself then.’

‘But until then I’m the boss?’

‘Yes,’ he said sullenly.

‘And you take my orders?’

His fists tightened but he held himself in. ‘Yes.’

‘Then here’s your first one. You don’t do a damn’ thing without consulting me first.’ I turned to go up the companionway, got half-way up, then had a sudden thought and went below again.

I said, ‘And there’s another thing I want to tell you. Don’t get any ideas about double-crossing me or Walker, because if you do, you’ll not only have me to contend with but Metcalfe as well. I’d be glad to give Metcalfe a share if you did that. And there wouldn’t be a place in the world you could hide if Metcalfe got after you.’

He stared at me sullenly and turned away. I went on deck.

Walker was sitting in the cockpit. ‘Did you hear that?’ I said.

He nodded. ‘I’m glad you included me on your side.’

I was exasperated and shaking with strain. It was no fun tangling with a bear like Coertze – he was all reflex and no brain and he could have broken me as anyone else would break a matchstick. He was a man who had to be governed like a fractious horse.

I said, ‘Dammit, I don’t know why I came on this crazy trip with a dronkie like you and a maniac like Coertze. First you put Metcalfe on our tracks and then he clinches it.’

Walker said softly, ‘I didn’t mean to do it. I don’t think I told Metcalfe anything.’