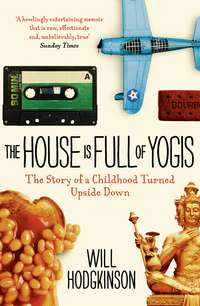

The House is Full of Yogis

He didn’t say anything.

The gerbil I chose was a tiny rat-like creature with a twitching nose and a nervous disposition. I knew when I saw him that he was the one: he was away from his little brothers and sisters in the cage, alone, clawing at the glass. He needed me. I called him Kevin. With the notes I took from Nev’s drawer I also bought a little cage with a wheel. Then, with the money left over, I bought Smash Hits by Jimi Hendrix. It was educational. Nev would have wanted it that way.

Kevin didn’t appreciate his new surroundings. My bedroom was large, and my now semi-permanent Scalextric track looked like a raceway that had fallen on hard times: a grandstand only half painted, racing cars in the pit stop desperately in need of repair, and spectators missing limbs, although the last detail was a punishment from Tom in retaliation for stealing and losing then lying about stealing and losing his Sony Walkman. I had imagined Kevin would feel powerful in this miniature society in decline, but to my disappointment he scrambled under the bed the moment I released him from his cardboard box. Even the exciting sight and sound of cars going around the track wouldn’t entice him out of his shadowy hiding place.

With Kevin unavailable, I made the most of my second purchase of the day. I put the two speakers of my little stack stereo system on the carpet, facing each other, and my head between them. The music was incredible. From the heavy rock of ‘Purple Haze’ to the tenderness of ‘The Wind Cries Mary’, it offered transports into distant lands. I closed my eyes and let the magic carpet ride of Jimi Hendrix take me on a journey.

‘What is this shit?’

Tom was standing over me, the sleeve in his hand. His mouth turned down into a grimace as he held his head back. ‘Good God, not Jimi Hendrix. This is the kind of hippy vomit the idiots at school listen to. I can almost smell the patchouli oil. Crap.’

‘That’s a matter of opinion.’

‘No. Fact.’

‘By the way, what’s happened to your hair?’

Tom had undergone a radical transformation. Earlier that day, he had a floppy fringe befitting a public school boy who liked to walk around the grounds of Westminster School in his gown, spouting Ovid. Now the back and sides of his head were shaved and he had a big sprout of orange hair puffing out of the top, like a prize mushroom. He was dressed differently too. An oversized black jumper, black drainpipe jeans and brothel creepers had replaced the velvet jacket and bowtie he usually wore.

‘What?’ he said, glowering.

I stared at Tom for a while. I made sure he noticed my eyes going from the top of his head to the bottom of his feet. Then I put my head back between the speakers and, after a little chuckle, said, ‘Nothing.’

‘What, you little shit?’

‘It’s ‘Hey Joe’. My favourite song.’

Tom attacked me. He knocked the record and the stylus made a horrible scratching sound. ‘You idiot!’ I screamed, in a much higher-pitched tone than I would have liked. ‘If you’ve damaged it you’re buying a new one.’

Tom got off me and turned his head in confusion. ‘What was that?’

‘What?’

‘I just saw some sort of animal run out of the room.’

‘Oh no. Kevin!’

As my terrible luck would have it, he ran into Mum and Dad’s room. At least Nev would be too severely ill to notice him, and perhaps even me catching him, so I crept in. Mum was in there, alongside a man who was taking Nev’s temperature and looking serious.

‘The problem is that it has reached his blood stream,’ said the doctor. ‘It’s rare to get it this badly. Has he been run down recently?’

‘He’s always had to watch his vitamin levels. He’s got a weak constitution.’ Mum crossed her arms and nodded, as if this diagnosis brought some sort of finality to the situation. ‘Everyone else recovered ages ago. He’s been overworked … By the way, this is my son Will. What is it, darling?’

I could see Kevin, twitching his nose underneath a small round table in the corner of the room. All I needed to do was encourage him to run back out again. Then I could grab him and put him in his cage.

As I moved towards the little table, slowly and sideways, like a drugged crab, I said: ‘I … I just had to see Nev. I’ve been worrying about him so much.’

‘Liar,’ came Tom’s voice from the other side of the door.

‘Will, if this is one of your pranks …’

This required extra effort. ‘It’s not,’ I cried, wobbling my voice and wishing for tears, although they never came. ‘I don’t want to lose him.’ I turned my head away. Kevin was no longer under the table. I had no idea where he was. I sat down on the side of the bed and hid my head in my hands while secretly staring at the floor, watching out for a gerbil.

The doctor gave a deep, low sigh. ‘This is a difficult time for your family. But I’d like to emphasize how in most cases like this the patient does pull through. The best course of action is to let your husband get as much rest as he can.’

Kevin was right next to the bed. It should have been achievable to just lean down and grab him, but I didn’t want Mum and the doctor to see so I lay face down on the side of the bed and sobbed while stretching my arm out and inching it ever closer to the gerbil.

‘Will, I know it’s upsetting,’ said Mum, ‘but we really need to leave Nev to get as much peace and quiet as possible.’

Then she screamed.

‘A rat!’ She jumped onto the bed.

Nev groaned. I managed to get hold of Kevin, who bit me. I put him in my shirt and dropped him into his cage. Mum had to wait for the doctor to leave before she had the chance to come in and start yelling.

My twelfth birthday came while Nev was still in bed, woefully thin and exhausted by trips to the bathroom but no longer on the verge of death. He and Mum got me a BMX bike, which I had long dreamed of owning. Tom bought me a record. He hadn’t bothered to wrap it up and it was second-hand; the album sleeve was ripped and over the price sticker in the top right hand corner he had scribbled ‘Happy Birthday Scum’. It was The Byrds’ Greatest Hits.

‘Who are The Byrds?’

‘Presumably you have heard of The Beatles? They’re the American version, ergo, better suited to your limited intellectual capacity.’

Reader, I hit him.

With Nev out of action and Mum working late whenever she got the opportunity, we relied increasingly on a local girl called Judy to look after us. One afternoon when Tom was out, an afternoon Will Lee and I had intended to occupy by building Kevin his very own adventure park out of Mum’s new Salvatore Ferragamo leather boots and a few toilet rolls, Judy turned up with three other teenage girls and a Ouija Board.

‘What’s a Ouija board?’ I asked.

‘It’s a way of contacting the spirits of the dead,’ said Judy. ‘You normally speak to people who used to live in the house you’re in, but you never know who you’ll find. We got the ghost of Jim Morrison once. Turns out he had a thing for teenage girls from Richmond.’

Will and I studied the board. It had ornate and slightly scary Edwardian etchings of a smiling sun, a frowning moon and some ghostly silhouettes. The letters of the alphabet were spelled out, and there were also the words ‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘goodbye’, for the spirits to use when in a hurry.

I looked at this group of teenagers. Four girls, at a guess aged around seventeen, in pixie boots and legwarmers. They set up the board and argued about which one of them Jim Morrison’s ghost had been talking about when he said she was ‘well hot’. Will Lee and I hovered around them, poked our heads over their shoulders, and generally tried to get their attention.

‘Leave us alone,’ said one of the girls, after they turned the lights off and put a single candle in the middle of the kitchen table. ‘We need to concentrate for our séance to work.’

As we left them to it, they put all of their hands together on the plastic heart-shaped object designed to move around the board.

‘Voices from the Other Side, talk to us.’

‘It’s moving,’ one of them shrieked.

On the other side of the door, meanwhile, we did our best to listen in. They could hear us sniggering.

‘Go away.’

We stuck our heads round the door. ‘What’s happening? Found any dead people?’

‘We’ve contacted a Victorian man called Bartholomew,’ our babysitter replied. ‘He had two wives and six children, although three of them died in childbirth and one grew up to become a whore in Islington.’

‘What’s a whore?’ asked Will.

The girls refused to tell us, and for that reason we decided to play a trick on them. Nobody had got round to fixing the milk hatch that had broken off its hinges, so its little wooden door was simply jammed into position on the outside wall of the kitchen but not actually held on by anything. This would allow us our revenge. We went round to the side of the house and tried to listen to the girls’ conversation with Bartholomew. It was impossible; only when they giggled could we hear them. So we waited until they weren’t giggling. That would mean they were absorbed in a tense moment of Ouija board mysticism.

‘OK,’ I whispered to Will, ‘one, two, three.’

We pushed the door of the milk hatch as hard as we could. We heard chilling, terrified screams. We ran round to see what had happened. The milk hatch had landed right in the centre of the Ouija board, smashing the plastic heart. The girls were standing up, away from the table, with widened eyes and their hands over their mouths. Pasty-faced suburban girls, they were even paler than usual.

‘I’m never doing it again.’

‘We’re dealing with forces we don’t understand.’

‘We just asked Bartholomew a question,’ said Judy, ‘and that thing flew onto the table.’

‘What was the question?’ said Will.

The girls shuddered in unison. ‘“How did you die?”’

Without Nev to help me with homework, school became one form of torture after another. If it wasn’t games – freezing on the brittle mud of a football field as a defender after being picked last, apart from Bobby Sultanpur who had one leg shorter than the other – it was science, with Mr Mott threatening to whack us with his paddle stick if we did so much as set fire to the annoying kid’s blazer with a Bunsen burner. Music lessons were a waste of time altogether. Our teacher, Mr Stuckey, had a vague connection with Andrew Lloyd Webber, which meant that our school provided the boys for the choir in the West End production of Evita. About half of my class was in the choir. They got five pounds a night, they went up to Soho on a coach once or twice a week, and they had Mr Stuckey’s full attention. He sat around a piano and trained the chosen ones while the Evita rejects had to sit in a cold, grey back room and amuse themselves in whatever ways unsupervised twelve-year-old boys could.

Art was appalling, but not because of the art teacher. He was a man with red hair and a beard in a fisherman’s jumper who told us that Mrs Oates, our English teacher, who put on white lacy gloves before handling a piece of chalk and got emotional as she told us the word gay had been ruined forever, slept in the same bed as a cannon. It was years before we discovered her husband was Canon Oates, a high-ranking member of the clergy. Art was appalling because I couldn’t draw or paint. The concept of perspective eluded me. You had to have something in school to be good at, even if you were diabolical at everything else. I might have scraped through English with a bit of dignity if it hadn’t been for Mrs Oates and her horrific taste in literature. She considered A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin a masterpiece and dismissed The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, which I had read over an afternoon of uncontrollable laughter, as vulgar. And sooner or later it always came back to the Bible, surely the most boring book ever written. The only lesson that was vaguely bearable was French, and that was because Mr Gaff had a fascination with combustion engines which meant that once you got him on the subject he would spend the entire lesson talking about them rather than the clauses and declensions he was meant to be concentrating on. It felt like a minor victory.

Worst of all was the comment I got when another ink-blot-stained exam paper came back scrawled in angry red marker pen. ‘After your brother, you’re a bit of a disappointment. Aren’t you, Hodgkinson?’

If only those teachers could see the torments Tom put the rest of the family through. While Nev was still a silent and bedridden presence, Tom refused to wear the anorak Mum had bought him, even though the very air was soaked through. Fog and rain had turned the suburbs of London into a dark grey, mud-splattered pit of dirty concrete and squelching grass.

‘For a start it’s too big,’ said Tom, throwing the anorak to the ground. ‘Secondly, the zip doesn’t work. And thirdly, everyone will laugh at me. You haven’t been to school in thirty years. You don’t know what it’s like.’

‘It’s an anorak. Everyone else’s mums will have insisted they wear one,’ shouted Mum, picking it up off the floor and thrusting it back at Tom. ‘You don’t get picked on because of what you wear. You get picked on for not standing up for yourself.’

‘And I’m not going to stand here listening to you. You’re not sophisticated enough to know what it’s like to be a scholarship boy.’

A week after the birthday party, I came home from school with the intention of going straight out on my BMX and heading over to the woods, where there was a stream in dire need of being jumped over. Then I saw Nev, sitting by our kitchen table, nursing a cup of tea. Mum was next to him. He looked peaceful, serene and frail. It was the first time in two months I had seen him out of his pyjamas.

‘Hello, Sturchos,’ he said, his old familiar grin back in place. ‘How have you been?’

He looked older. Nev had always been a young dad, and young for his age – he was thirty-eight and he could pass for a decade less – but now he looked weathered, reduced. He was extremely thin, like a skeleton rattling about in jeans and a jumper, and the skin was stretched over his knuckles. His curly blonde hair was thin and neat; he must have had a haircut that afternoon. I told him I was fine except that on the day of my birthday the kids at school gave me the bumps – throwing you up in the air for as many times as match your age – and then, when the bell for the end of break went, they all ran off as the bumps hit twelve, leaving me to land on the ground with a thud.

‘I’m afraid the same thing happened to me,’ he said. ‘Boys can be terribly stupid. The most important thing is not to let it affect you too much. You can’t control the way other people behave, but you can control the way you respond to their behaviour.’

We chatted about how Nev had been feeling during his two months of serious sickness, as Mum looked at him in a way I hadn’t seen before. She wasn’t teasing and playful, as she had been with Nev when Tom and I were younger, and she didn’t show the resentment and competitiveness that had made the boat trip so tense. She was genuinely concerned about him. There was some kind of affection there, like he was a friend who had gone through a hard time and it was her job to make him feel better. She brought him a bowl of soup as he tried to explain what it had been like to be so ill.

‘In a strange way it felt positive,’ he said, lightly. ‘A lot of it was extremely uncomfortable, but all the pain, and being so sick, made me stop worrying about work for once. It forced me to take a breather. I realized how a lot of things that have been bothering me, such as not having a secretary or not getting my own office, aren’t nearly as important as I thought they were. I guess the most significant thing is that it feels as if this illness has been telling me something.’

‘Like, don’t eat chicken cooked by Penny Lee?’

‘I mean it’s shown me something about my ego,’ he said. ‘It was taking over. And at the height of my fever … it was either a flash of light or total darkness, but for a moment I felt a sense of release from the weight of the world. It was beautiful.’

‘Maybe you went to the Other Side,’ I said breathily. I recounted the tale of the Ouija board, and Bartholomew, and the milk hatch flying onto the table. ‘Now don’t tell me that’s a coincidence.’

Nev smiled, but in a strained way. He had been speaking in a slightly fey tone, which I found uncomfortable. It was like when I saw him talking to the burly dad of a friend and was gripped with the fear that he was about to challenge Nev to a fight.

‘Anyway, Mum and I have got something we need to talk to you about.’

They looked solemn.

‘You’re not getting a divorce, are you?’

Mum was sending Nev off to Florida for a month to recuperate, build his strength up, and relax in a stress-free environment. He was to stay with a friend of a friend in a house by a lake in a place called, appropriately enough, Land O’ Lakes. The friend of a friend ran the house as something of a retreat, inviting people to stay with them free of charge on the proviso that they use the time there for quietude and contemplation. ‘He’s not allowed to do any work,’ said Mum. ‘I’m not going to let him tell the paper where he is. It’s going to be a total rest.’

‘Sorry to rush off as soon as I’m able to talk to you,’ said Nev. ‘But this way I’ll be able to recover properly and then we can do all kinds of things together. We can climb trees. Have conker fights. Build dens in the woods. Play games on the Atari.’

‘I’ll tell you what I’d like to do,’ I said, thinking of a family ritual that hadn’t happened in a while. ‘I’d like us to bomb down to Brighton after having loads of spare ribs in the Royal China, spend the afternoon on the pier, have a pinball tournament, play air hockey and go on the beach and try to hit a rusty tin can with a pebble. And then we can stop off at a country pub on the way back to London and you can drink beer while me and Tom have a Coke and a packet of crisps. Can we do that again?’

‘Of course we can,’ said Nev, warmly. ‘That sounds like fun.’

But we never did.

4

Nev Returns

While Nev was off in Florida, I made a new friend. Sam Evans lived in Hammersmith, West London, in a flat. All of my suburban chums lived in houses – not big houses, but houses nonetheless – so a flat seemed terribly cosmopolitan. You walked up a flight of stairs to enter the living room, where Sam’s mother Erica slept on a bed that folded out of the sofa. Upstairs was Sam’s room. He had a poster of Judge Dredd, a Commodore 64 computer and a large bookshelf with grown-up novels; apart from Tom, I had not come across a boy who had read A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich or Animal Farm. I poked my head into Sam’s sister’s room. It was phenomenally untidy: clothes piled everywhere, ashtrays – shocking in itself – and posters of David Bowie on the walls.

‘Your sister looks cool.’

‘Are you joking? Let’s go downstairs and get Mum to make us some French toast.’

Erica Evans, who was American and wore oversized glasses and bright yellow dungarees, worked for something called the Institute For Psychic Research. ‘We’re all psychic,’ she said in a matter of fact way as she worked through a pile of papers on the dining table. ‘It’s just a question of unlocking the power within.’ I told her about the Ouija board episode. ‘Yeah, you get some pretty restless spirits with Ouija,’ she said, nodding enthusiastically. ‘Ghosts are dead people who haven’t resolved their issues in this world, so they cling on to the living. Best not to mess around with that shit.’

Sam picked up a plastic bag full of white powder that was sitting on the top of a bookcase and said, winking at me, ‘Are you selling cocaine again, Mum?’

‘I realized this morning we had run out of washing powder and I didn’t have time to go out and buy some more, so I asked one of the gay guys downstairs if I could borrow some. He was wearing incredibly tight jeans, and I swear, he had no penis whatsoever. I couldn’t stop staring. I hope he didn’t notice.’

I was incapable of contributing to this conversation.

It got worse, or rather, better, when Erica had to go out, presumably for a combination of cocaine selling, ghost hunting and the examining of tiny penises. Sam’s flat had a video machine and he suggested we watch a film called The Man Who Fell to Earth. ‘David Bowie plays an alien. Fancy it?’

‘OK,’ I said.

‘It’s got, like, a blowjob scene, but it’s no big deal.’

‘Cool,’ I said, with a shrug. What was a blowjob?

It was like moving to a foreign country for the afternoon.

The television was on the floor, under the stairs, which meant that the best way to watch it was lying down. Perhaps a family’s discipline could be measured by the height at which they relaxed. At Will Lee’s house, with the exception of the beanbags in the attic, stiff wooden chairs with high, straight backs kept you at a minimum of two feet off the ground at all times, which seemed unfair considering his mother was under five feet tall and had to climb onto them. In our house everything levelled out at a conventional foot and a half. At the Evans’s, sitting above carpet level was for the unenlightened.

The film was made up of a series of exotic images, none of which I understood but which stayed with me for years afterwards: David Bowie watching a bank of televisions; wandering around an arid, distant planet; painted figures performing a ritualistic dance in a Japanese restaurant; and a sex scene with the aforementioned blowjob, something that before then I didn’t actually know existed. As the months passed those images kept playing back at me, ever more jumbled and confused but still with vivid flashes, and always associated with the first time I saw Sadie Evans.

It was some time near the end of the film when she came up the narrow stairs and into the flat. She must have been about fourteen, the same age as Tom, but she looked older. She had lank reddish hair cut to her shoulders and pale, pimple-flecked skin. She was wearing denim jeans, a denim jacket, a studded belt and a Motorhead T-shirt. She hovered over us, hands on her hips.

‘Who said you could watch my Man Who Fell to Earth?’

‘Who said I couldn’t?’ Sam replied, not looking up at her.

‘You’re lucky,’ she said with a curl of the lip, ‘that I’m in a good mood.’ She kicked her brother in the ribs. Sam yelped and called her an idiot. She cocked her head at me and said, ‘Who’s this?’

‘I … I … I … I’m … Wuh-whu-whu … Will.’

‘You will what?’

‘That’s his name?’ said Sam, eyes raised heavenwards.

For some reason this appeared to annoy her, as she stomped off to her room. But halfway up the stairs she stopped, looked at me, and winked. She took the last remaining steps at a slow, steady, sashaying pace.

Half an hour later, the telephone went. It was Mum, telling me it was time to come home: Nev had returned. I left the flat as if in a trance, with only a hazy impression of taking the tube for the three stops from Turnham Green to Richmond, walking up the alleyway at the side of the station and bashing into a man who told me to watch out where I was going, then crossing Queens Road and getting honked at by the oncoming traffic.

I had met girls before. Not many, but I had, and I knew what they looked like and how they sounded. What was it about Sadie, a girl I had known for a total of twenty-six seconds, which caused this strange feeling?

Who could I talk to? Tom was out of the question. Will Lee was unlikely to be of much help. A boy that spent after-school sessions classifying fossils could not be expected to know the mysteries of love. Nev would surely know what to do and what to say. He had intimate knowledge of difficult women and it looked too as though once more he had the strength to take on his paternal duties. After I had crashed through the back door and opened the fridge to glug orange juice straight from the carton, I saw the family, sitting around the table, looking at me expectantly.