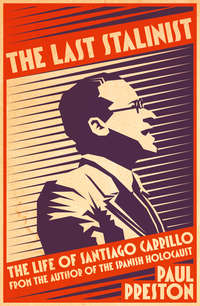

The Last Stalinist: The Life of Santiago Carrillo

That Carrillo was fully aware of this is demonstrated by the minutes of the meeting of the Junta de Defensa on the night of 11 November 1936. One of the anarchist consejeros asked if the Cárcel Modelo had been evacuated. Carrillo responded by saying that the necessary measures had been taken to organize the evacuations of prisoners but that the operation had had to be suspended. At this, the Communist Isidoro Diéguez Dueñas, second-in-command to Antonio Mije at the War Council, declared that the evacuations had to continue, given the seriousness of the problem of the prisoners. Carrillo responded that the suspension had been necessary because of protests emanating from the diplomatic corps, presumably a reference to his meeting with Schlayer. Although the minutes are extremely brief, they make it indisputably clear that Carrillo knew what was happening to the prisoners if only as a result of the complaints by Schlayer.109

In fact, after the mass executions of 7–8 November, there were no more sacas until 18 November, after which they continued on a lesser scale until 6 December. The sacas and the executions have come to be known collectively as ‘Paracuellos’, the name of the village where a high proportion of the executions took place. Those executions constituted the greatest single atrocity perpetrated in Republican territory during the war. Its scale is explained but not justified as a response to the fear that rebel forces were about to take Madrid. Whereas previous sacas had been triggered by spontaneous mass outrage provoked by bombing raids or by news brought by refugees of rebel atrocities, the extra-judicial murders carried out at Paracuellos were the result of political-military decisions. The evacuations and subsequent executions were organized by the Council for Public Order but could not have been implemented without help from other, largely anarchist elements in the rearguard militias.

The brief interlude after the mass sacas of 7 and 8 November was thanks to Mariano Sánchez Roca, the under-secretary at the Ministry of Justice who arranged for the anarchist Melchor Rodríguez to be named Special Inspector of Prisons.110 The first initiative taken by Melchor Rodríguez on the night of 9 November was decisive. Hearing that a saca of 400 prisoners was planned, he went to the prison at midnight and ordered that all sacas cease and that the militiamen who had been freely moving within the prison remain outside. He forbade the release of any prisoners between 6 p.m. and 8 a.m., to prevent them being shot. He also insisted on accompanying any prisoners being transferred to other prisons. In consequence there were no sacas between 10 and 17 November, when Melchor Rodríguez was forced to resign his post by Juan García Oliver, the anarchist Minister of Justice. His offence was to have demanded that those responsible for the killings be punished.111 After his resignation, the sacas started again.112

Manuel Azaña, who had succeeded Alcalá Zamora as President of the Republic, and at least two government ministers in Valencia (Manuel Irujo and José Giral) had learned about the sacas.113 Indeed, a speech made on 12 November by Carrillo suggests that, at the time, secrecy was not a major priority. Speaking before the microphones of Unión Radio, he boasted about the measures being taken against the prisoners:

it is guaranteed that there will be no resistance to the Junta de Defensa from within. No such resistance will emerge because absolutely every possible measure has been taken to prevent any conflict or alteration of order in Madrid that could favour the enemy’s plans. The ‘Fifth Column’ is on the way to being crushed. Its last remnants in the depths of Madrid are being hunted down and cornered according to the law, but above all with the energy necessary to ensure that this ‘Fifth Column’ cannot interfere with the plans of the legitimate government and the Junta de Defensa.114

On 1 December 1936, the Junta de Defensa was renamed the Junta Delegada de Defensa de Madrid by order of Largo Caballero. Having led the government to Valencia, the Prime Minister was deeply resentful of the aureole of heroism that had accumulated around Miaja as he led the capital’s population in resisting Franco’s siege. Thus Largo Caballero wished to restrain what he considered the Junta’s excessive independence.115 Serrano Poncela had already left the Public Order Delegation at some point in early December and his responsibilities were taken over by José Cazorla.

At the end of the war, Serrano Poncela gave an implausible account of why he had left the Public Order Delegation. He told the Basque politician Jesús de Galíndez that he did not know that the words ‘transfer to Chinchilla’ or ‘release’ on the orders that he signed were code that meant the prisoners in question were to be executed. The use of such code could have been the method by which those responsible covered their guilt – as suggested by the phrase ‘with responsibility to be hidden’ in the minutes of the meeting of the evening of 7 November. Serrano Poncela told Galíndez the orders were passed to him by Santiago Carrillo and that all he did was sign them. He told Galíndez that, as soon he realized what was happening, he resigned from his post and not long afterwards left the Communist Party.116 This was not entirely true since he held the important post of JSU propaganda secretary until well into 1938. In an extraordinary letter to the Central Committee, written in March 1939, Serrano Poncela claimed that he had resigned from the Communist Party only after he had reached France the previous month, implying that previously he had feared for his life. He referred to the disgust he felt about his past in the Communist Party. He also claimed that the PCE had prevented his emigration to Mexico because he knew too much.117 Indeed, he even went so far as to assert that he had joined the PCE on 6 November 1936 only because Carrillo had browbeaten him into doing so.118

Subsequently, and presumably in reprisal for Serrano Poncela’s rejection of the Party, Carrillo denounced him. In a long interview given to Ian Gibson in September 1982, Carrillo claimed that he had had nothing to do with the activities of the Public Order Delegation and blamed everything on Serrano Poncela. He alleged that ‘my only involvement was, after about a fortnight, I got the impression that Serrano Poncela was doing bad things and so I sacked him’. Allegedly, Carrillo had discovered in late November that ‘outrages were being committed and this man was a thief’. He claimed that Serrano Poncela had in his possession jewels stolen from those arrested and that consideration had been given to having him shot.119 Serrano Poncela’s continued pre-eminence in the JSU belies this. Interestingly, neither in his memoirs of 1993 nor in Los viejos camaradas, a book published in 2010, does he repeat these detailed charges other than to say that it was during their time together in the Consejería de Orden Público that their differences began to emerge.120

The claim that he personally had nothing to do with the killings was repeated by Carrillo in his memoirs. He alleged that the classification and evacuation of prisoners was left entirely to the Public Order Delegation under Serrano Poncela. He went on to assert that the Delegation did not decide on death sentences but merely selected those who would be sent to Tribunales Populares (People’s Courts) and those who would be freed. His account is brief, vague and misleading, making no mention of executions and implying that the worst that happened to those judged to be dangerous was to be sent to work battalions building fortifications. The only unequivocal statement in Carrillo’s account is a declaration that he took part in none of the Public Order Delegation’s meetings.121 However, if Azaña, Irujo and Giral in Valencia knew about the killings and if, in Madrid, Melchor Rodríguez, the Ambassador of Chile, the Chargé d’Affaires of Argentina, the Chargé d’Affaires of the United Kingdom and Félix Schlayer knew about them, it is inconceivable that Carrillo, as the principal authority in the area of public order, could not know. After all, despite his later claims, he received daily reports from Serrano Poncela.122 Melchor Rodríguez’s success in stopping sacas raises questions about Santiago Carrillo’s inability to do the same.

Subsequently, Francoist propaganda built on the atrocity of Paracuellos to depict the Republic as a murderous Communist-dominated regime guilty of red barbarism. Despite the fact that Santiago Carrillo was just one of the key participants in the entire process, the Franco regime, and the Spanish right thereafter, never missed any opportunity to use Paracuellos to denigrate him during the years that he was secretary general of the Communist Party (1960–82) and especially in 1977 as part of the effort to prevent the legalization of the Communist Party. Carrillo himself inadvertently contributed to keeping himself in the spotlight by absurdly denying any knowledge of, let alone responsibility for, the killings. However, a weight of other evidence confirmed by some of his own partial revelations makes it clear that he was fully involved.123

For instance, in more than one interview in 1977, Carrillo claimed that, by the time he took over the Council for Public Order in the Junta de Defensa, the operation of transferring prisoners from Madrid to Valencia was ‘coming to an end and all I did, with General Miaja, was order the transfer of the last prisoners’. It is certainly true that there had been sacas before 7 November, but the bulk of the killings took place after that date while Carrillo was Consejero de Orden Público. Carrillo’s admission that he ordered the transfers of prisoners after 7 November clearly puts him in the frame.124 Elsewhere, he claimed that, after he had ordered an evacuation, the vehicles were ambushed and the prisoners murdered by uncontrolled elements. He stated, ‘I can take no responsibility other than having been unable to prevent it.’125 This would have been hardly credible under any circumstances, but especially so after the discovery of documentary proof of the CNT–JSU meeting of the night of 7 November.

Moreover, Carrillo’s post-1974 denials of knowledge of the Paracuellos killings were contradicted by the congratulations heaped on him at the time. Between 5 and 8 March 1937 the PCE celebrated an ‘amplified’ plenary meeting of its Central Committee in Valencia. Such a meeting, with additional invited participants, was midway between a normal meeting and a full Party congress. Francisco Antón, a rising figure in the Party and known to be Pasionaria’s lover, declared: ‘It is difficult to say that the fifth column in Madrid has been annihilated but it certainly has suffered the hardest blows there. This, it must be proclaimed loudly, is thanks to the concern of the Party and the selfless, ceaseless effort of two new comrades, as beloved as if they were veteran militants of our Party, Comrade Carrillo when he was the Consejero de Orden Público and Comrade Cazorla who holds the post now.’ When the applause that greeted these remarks had died down, Carrillo rose and spoke of the work done to ensure that the 60 per cent of the members of the JSU who were fighting at the front could do so ‘in the certain knowledge that the rearguard is safe, cleansed and free of traitors. It is not a crime, it is not a manoeuvre, but a duty to demand such a purge.’126

Comments made both at the time and later by Spanish Communists such as Pasionaria and Francisco Antón, by Comintern agents, by Gorev and by others show that prisoners were assumed to be fifth columnists and that Carrillo was to be praised for eliminating them. On 30 July 1937, the Bulgarian Stoyán Mínev, alias ‘Boris Stepanov’, from April 1937 one of the Comintern’s delegates in Spain, wrote indignantly to the head of the Comintern, Giorgi Dimitrov, of the ‘Jesuit and fascist’ Irujo that he had tried to arrest Carrillo simply because he had given ‘the order to shoot several arrested officers of the fascists’.127 In his final post-war report to Stalin, Stepanov wrote proudly that the Communists took note of the implications of Mola’s statement about his five columns and ‘in a couple of days carried out the operations necessary to cleanse Madrid of fifth columnists’. In this report, Stepanov explained how, in July 1937, shortly after becoming Minister of Justice, Manuel Irujo initiated investigations into what had happened at Paracuellos including a judicial inquiry into the role of Carrillo.128 Unfortunately, no trace of this inquiry has survived and it is possible that any evidence was among the papers burned by the Communist-dominated security services before the end of the war.129

What Carrillo himself said in his broadcast on Unión Radio and what Stepanov wrote in his report to Stalin were echoed years later in the Spanish Communist Party’s official history of its role in the Civil War. Published in Moscow, and commissioned by Carrillo when he became secretary general of the PCE, it declared proudly that ‘Santiago Carrillo and his deputy Cazorla took the measures necessary to maintain order in the rearguard, which was every bit as important as the fighting at the front. In two or three days, a serious blow was delivered against the snipers and fifth columnists.’130

Rather unexpectedly, at the meeting of the Junta Delegada de Defensa on 25 December 1936, Carrillo resigned as Consejero de Orden Público and was replaced by his deputy, José Cazorla Maure. He announced that he was leaving to devote himself totally to preparing the forthcoming congress which was intended to seal the unification of the Socialist and Communist youth movements. It was certainly true that a JSU congress was to be held, for which he was preparing an immensely long speech. However, it is very likely that the precipitate timing of his departure was also connected with an incident two days earlier.131 On 23 December, a Communist member of the Junta de Defensa, Pablo Yagüe, had been shot and seriously wounded at an anarchist control post when he was leaving the city on official business. The culprits then took refuge in the local anarchist headquarters, the Ateneo Libertario, of the Ventas district. Carrillo ordered their arrest, but the CNT Comité Regional refused to hand them over to the police. Carrillo then sent in a company of Assault Guards to seize them. At the meeting of the Junta at which this was discussed, he called for them to be shot.132 It was the prelude to a spate of revenge attacks and counter-reprisals. Ultimately, Carrillo failed in his demand for the Junta de Defensa to condemn to death the anarchists responsible for the attack on Yagüe, something which was beyond its jurisdiction. He was furious when the case was put in the hands of a state tribunal where the prosecutor refused to ask for the death penalty on the grounds that Yagüe had not shown his credentials to the CNT militiamen at the checkpoint.133

Despite the Yagüe crisis, there can be little doubt that Carrillo needed to devote time to the JSU. The organization had expanded massively since July 1936 and its importance in every aspect of the war effort can scarcely be exaggerated. The PCE’s determination to consolidate its control of the JSU could be seen in Carrillo’s role in the national youth conference held in January 1937 in Valencia. It replaced the congress which had initially been scheduled to establish the structure and programme of the new organization. A congress had formal procedures that required the election of representative delegates, and wartime circumstances made that virtually impossible. A conference had the advantage of permitting Carrillo to choose the delegates himself. Thus he was able to pack the proceedings with hand-picked young Communists from the battle fronts and the factories. He then exploited that to perpetrate the sleight of hand whereby the conference made decisions corresponding to a congress. To the astonishment and chagrin of those FJS members who still harboured the illusion that the new organization was ‘Socialist’, the entire event was organized along totally Stalinist lines. All policy directives were pre-packaged, there was virtually no debate and there was no voting.134

One of the delegates from Alicante, Antonio Escribano, reflected later that ‘Ninety percent of the young Socialists present did not know that Carrillo, Laín, Melchor, Cabello, Aurora Arnaiz, etc had gone over lock, stock and barrel to the Communist Party. We thought that they were still young Socialists and they were acting in agreement with Largo Caballero and the PSOE. If we had known that these deserters had betrayed us, something else would have happened.’135 The impression that the proceedings were carried out under the auspices of Largo Caballero was shamelessly given by Carrillo, who declared, ‘It is necessary to say that Comrade Largo Caballero has, as ever, or more than ever, the support of the Spanish youth fighting at the front and working in the factories. It is necessary to say here that Comrade Largo Caballero is for us the same as before: the man who helped our unification, the man from whom we expect much excellent advice so that, in defence of the common cause, the unity of Spanish youth may be a reality.’136

As newsreel footage revealed, apart from Julio Álvarez del Vayo and Antonio Machado, the poet and alcalde (mayor) of Valencia, the stage party was made up of Communists headed by Pasionaria, Dolores Ibárruri. Carrillo opened his long speech with thanks to the Communist Youth International, the KIM, for its support. He made especially fulsome reference to the KIM representative, Mihály Farkas, introduced as ‘Michael Wolf’, with whom his relationship was growing closer. No longer the revolutionary firebrand of the Cárcel Modelo, Carrillo explained that, while the Socialist Youth, the FJS, had tried to undermine the government in 1934, now the JSU supported the Republican government’s war effort. According to Carrillo’s close collaborator Fernando Claudín, Farkas/Wolf had considerable input into Carrillo’s speech. Thus the Comintern line was paramount in Carrillo’s talk of broad national unity against a foreign invader. Central to his rhetoric was the defence of the smallholding peasants and the small businessmen with some bitter criticisms of anarchist collectives. There was also the ritual denunciation of the POUM (the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista) as a subversive Trotskyist outfit. With the guidance of Codovila and Farkas/Wolf, Carrillo had already started down the road of linking the POUM to the Francoists. The primary function of the JSU was no longer the fomenting of revolution but the education of the masses – the basic reformist aspiration of the Republican–Socialist coalition for which he had previously excoriated Prieto and the PSOE centrists. This was Comintern policy, although it also made perfect sense in the wartime context.137

Carrillo boasted that the new organization had had 40,000 members immediately after its creation but now had 250,000. He placed special emphasis on the fact that the JSU was a completely new organization entirely independent of both the PSOE and the PCE, in which neither component had the right to demand its leadership. This was a sophistry to neutralize Socialist annoyance about the fact that, since Carrillo, Cazorla and Serrano Poncela had formally joined the PCE, the JSU executive now had eleven Communists to four Socialists.138 It was hardly surprising, given the primordial role of the Soviet Union in helping the Republic, that Carrillo should express such enthusiasm for the Communist Party. It would not be long before he would clinch his betrayal of his erstwhile patron.

In the light of Largo Caballero’s incompetence as a war leader, the PCE was increasingly determined to see his removal as Prime Minister. Within barely a month of the JSU conference, the opportunity arose with the disastrous fall of Málaga to rebel forces on 8 February. The disaster could be attributed to Largo Caballero’s mistakes as Minister of War and those of his under-secretary, General José Asensio Torrado. By mid-May, mounting criticism had forced Largo Caballero to resign and he was replaced by the Treasury Minister, Dr Juan Negrín. An internationally renowned physiologist, the moderate Socialist Negrín shared the Communist view that priority should be given to the war effort rather than to revolutionary aspirations. An early contribution to the process of undermining Largo Caballero’s reputation was made by Carrillo when, in early March 1937, he headed a delegation from the JSU to an amplified plenum of the Central Committee of the PCE. In his speech, he was especially savage in his criticism of the POUM. What entirely undermined his constant claims about the JSU’s independence was his hymn of praise to the Communist Party. Moreover, the way he referred to his pride in leaving past mistakes behind must have galled Largo Caballero: ‘Finally, we found this party and this revolutionary line for which we have fought all our life, our short life. We are not ashamed of our past, in our past there is nothing deserving of reproach, but we are proud to have overcome all the mistakes of the past and to be today militants of the glorious Communist Party of Spain.’ His remarks on his reasons for joining the PCE were even more devastating for Largo Caballero. He referred to ‘those who, when the rebels were nearing Madrid, set off for Valencia’. He went on to say that ‘many of those who today are attacking the JSU were among those who fled’.139

Despite the prominence that came with his earlier position in the Junta de Defensa de Madrid and now as leader of the JSU, Carrillo’s role within the Spanish Communist hierarchy was a subordinate one. He accepted this, doing as he was told with relish. At that March 1937 meeting, he was made a non-voting member of the PCE’s politburo. He attended and listened but took little part in the discussions – being, as Claudín put it, ‘simply the man whose job it was to make sure that the JSU implemented party policy. He did not belong in the inner circles where the important issues were discussed and debated by the delegates of the Comintern (Palmiro Togliatti, Boris Stepanov, Ernst Gerö, Vittorio Codovila), by the top Soviet diplomatic, military and security staff and by the most prominent leaders of the PCE (José Díaz, Pasionaria, Pedro Checa, Jesús Hernández, Vicente Uribe and Antonio Mije).’ Carrillo himself believed at this stage that he was simply not trusted enough to be admitted to these top-secret meetings and was determined to achieve that trust. Accordingly, he was careful to maintain excellent relations with the Comintern representatives, especially with Togliatti and Codovila, the man he regarded as his mentor. Codovila was certainly satisfied with the progress made by his pupil.140

The extent to which Carrillo had transformed himself into ‘his master’s voice’ was confirmed at the JSU National Committee meeting on 15–16 May 1937 – just as Largo Caballero was being removed from the government. Carrillo roundly criticized Largo Caballero’s supporters within the organization and called for their expulsion. Indeed, throughout 1937 and 1938, together with Claudín, Carrillo presided over the systematic elimination of his erstwhile Caballerista allies from the JSU. Claudín’s efforts earned him the nickname of ‘the Jack the Ripper of the JSU’ (el destripador de las juventudes). This process would return to haunt the PCE leadership at the end of the war.141

The importance of Carrillo’s position derived from the fact that the mobilization of the male population, in which the PCE played a key role beginning with the creation of the Fifth Regiment, relied on the continued expansion of the JSU. Its members filled the ranks of the Fifth Regiment and then of the newly created Popular Army as well as those of the Republic’s rearguard security forces. For most of the time during 1937 and 1938, Carrillo devoted himself to building up the PCE’s most valuable asset. However, because he was of military age and should have been in a fighting unit, it was arranged for him to meet his obligations by spending brief periods attached to the General Staff of the commander of Fifth Army Corps, Lieutenant Colonel Juan Modesto. He claimed later to have witnessed parts of the battles of Brunete, Teruel and the Ebro. This later provoked outraged jibes by General Enrique Líster. It is almost certainly the case that any visits to the battle front were made in order to check on the JSU’s many political commissars. However, Carrillo’s subsequent attempts to fabricate an heroic military career in response to Líster’s accusations of cowardice were perhaps unnecessary. He could legitimately have argued that he had made a substantial contribution to the Republican war effort through his work in terms of the political education of the great influx of new recruits.142