The Times How to Crack Cryptic Crosswords

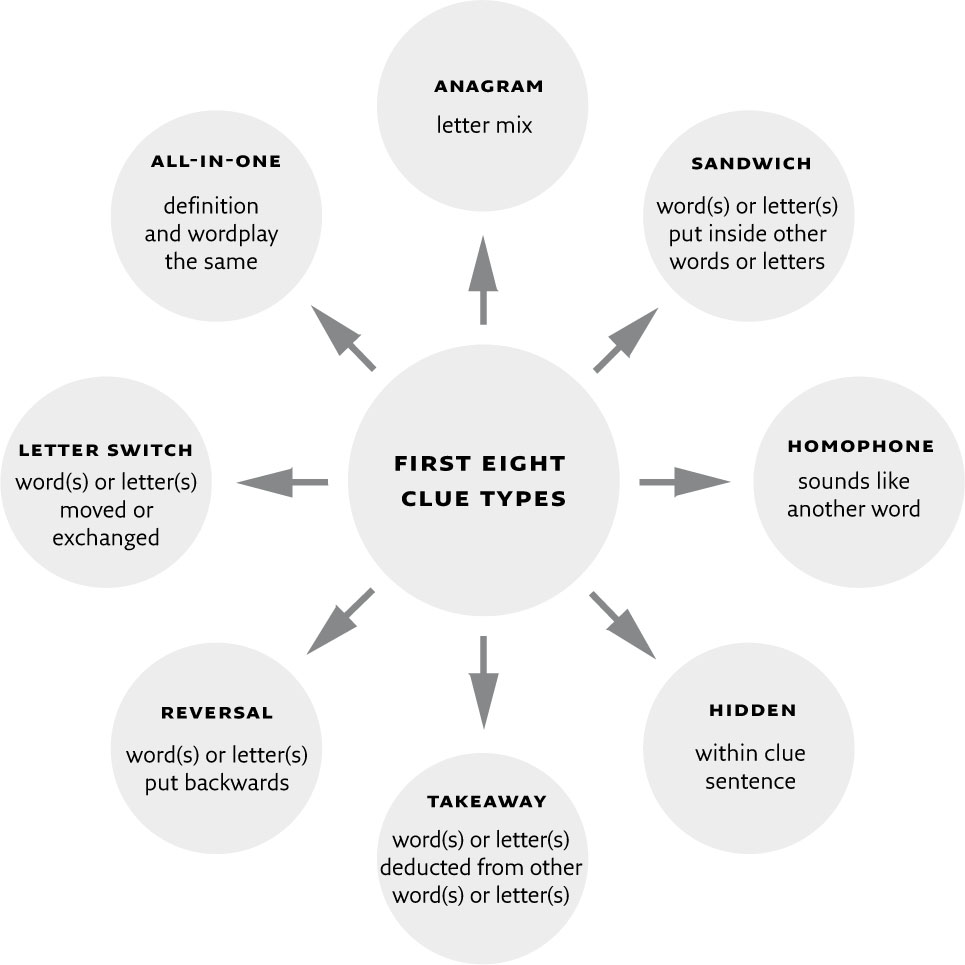

ANAGRAM CLUE: President saw nothing wrong (10)

For the remaining group of four, it’s usually a case of informed guesswork rather than indicators. This may seem unreasonable and impossible for the novice solver but I aim to prove that this is not really the case.

In the meantime, this may be a good time to point out that trial and error and/or inspired guesswork are part and parcel of good solving. This is reinforced by the clueing practice of all good setters whereby the clue type will nearly always become clear on working backwards from the solutions. Indeed, when a solver sees the solution the following day, he or she should only rarely be left thinking (as Ximenes put it):

“I thought of that but I couldn’t see how it could be right.”

We will now proceed to examine in detail all clue types and their indicators, with one and sometimes two examples of each type.

3: Clue Types and Indicators in Detail

“Give us a kind of clue.” W.S. Gilbert, Utopia Limited

Until Chapter 8, we’ll keep it simple with regard to clue types. In later chapters we will see that the clue types can and often do overlap, involving more than one sort of manipulation of letters or words within any one clue.

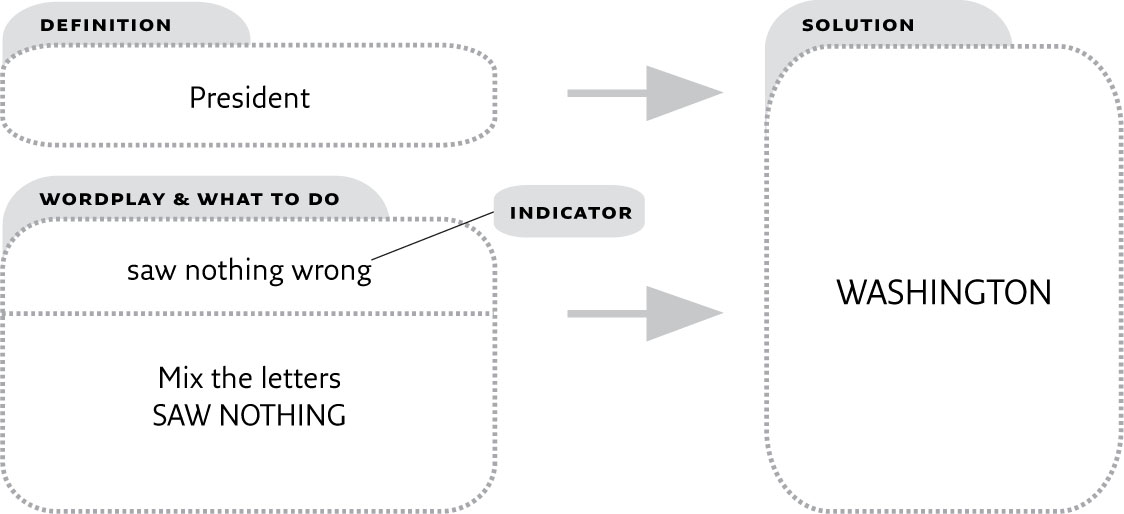

The first eight clue types

We will now examine each of the eight clue types in detail, together with their indicators, and offer some example clues. To give yourself solving practice, you may wish from now on to cover up the bottom part of the diagram that contains the solution and wordplay.

The first eight types are shown in the circular chart below, and we shall take each in turn, working clockwise from the top.

1. The anagram clue

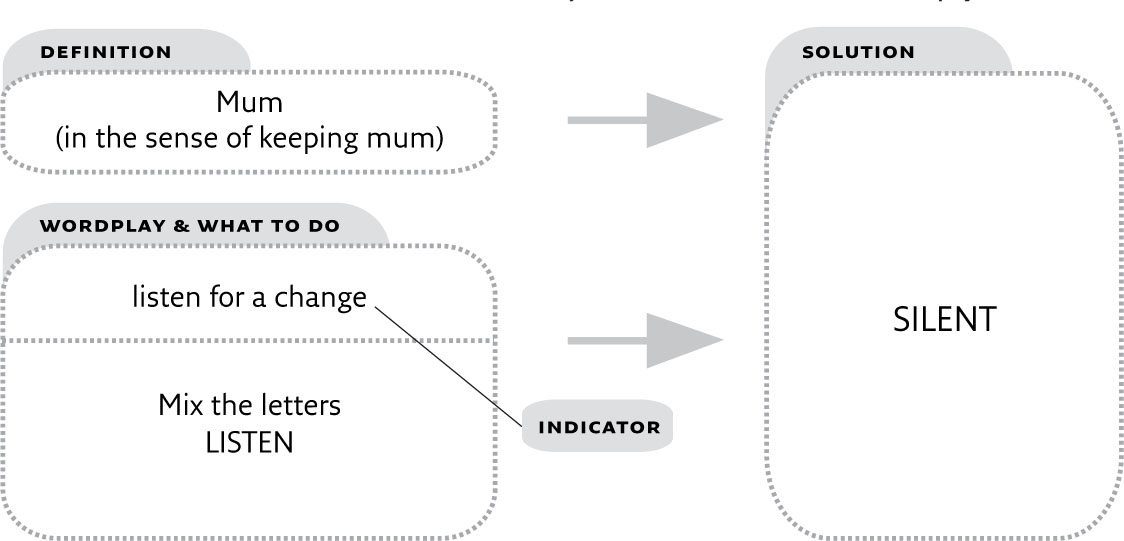

An anagram, sometimes termed a letter mix, is a rearrangement of letters or words within the clue sentence to form the solution word or words.

The letters to be mixed (the anagram fodder) may or may not include an abbreviation, a routine trick for old hands but, as I have observed, a cause of some discomfort for first-timers.

ANAGRAM CLUE: Mum, listen for a change (6)

This next example is an anagram clue with a linkword:

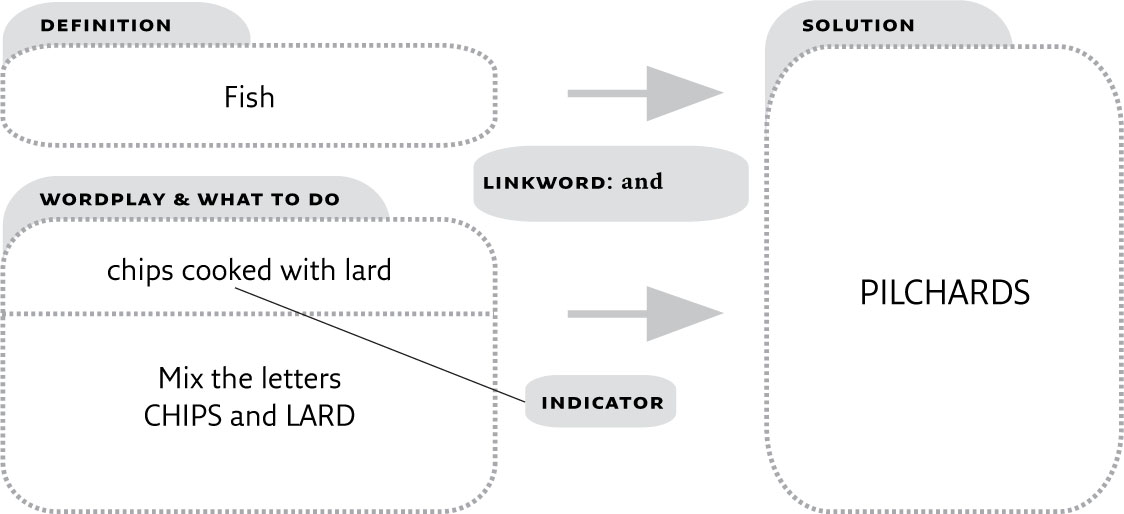

ANAGRAM CLUE: Fish and chips cooked with lard (9)

The third example is one wherein the anagram fodder goes well with the definition to form a remarkably accurate whole:

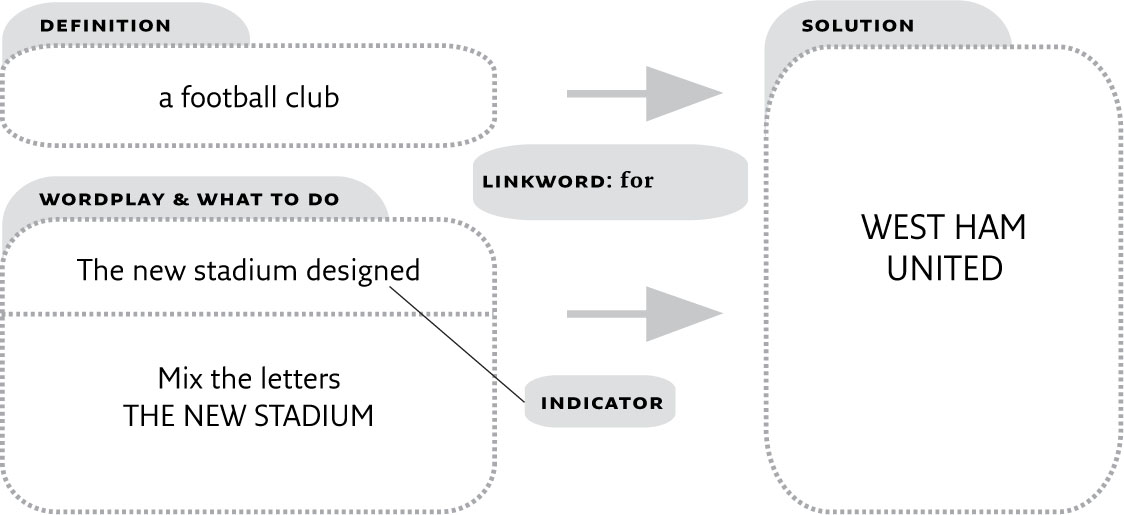

ANAGRAM CLUE: The new stadium designed for a football club (4,3,6)

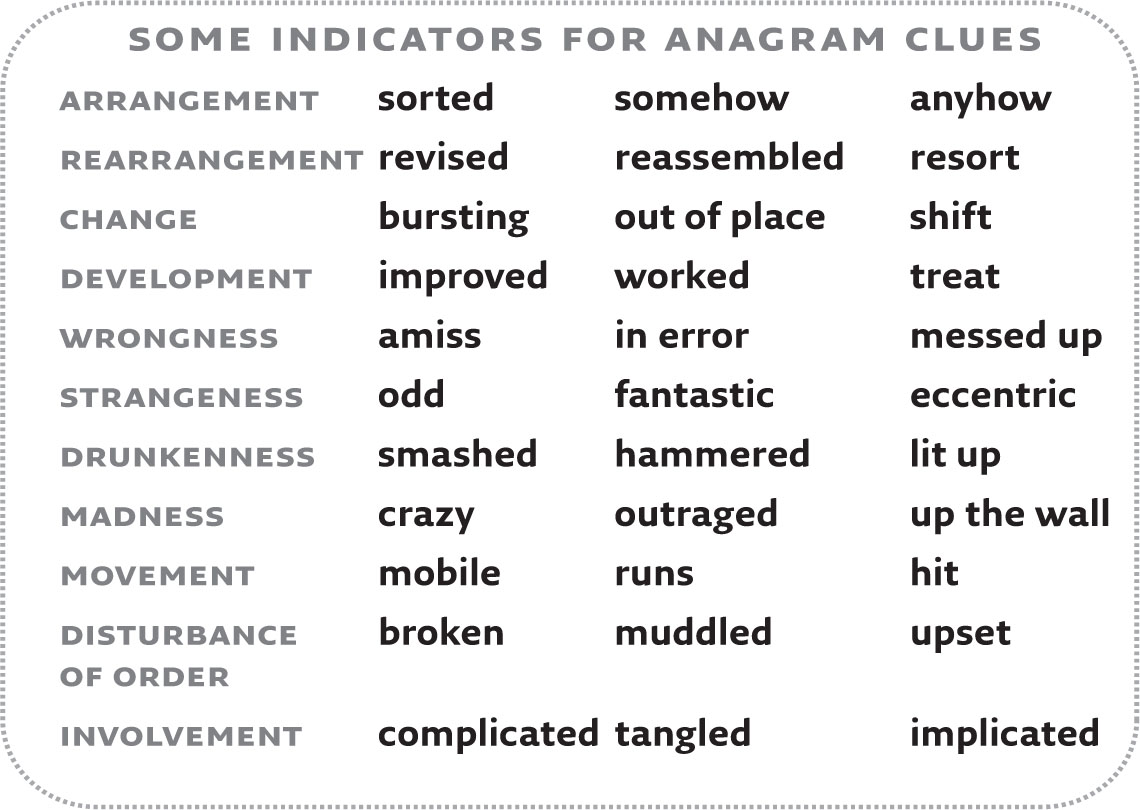

For is a linkword here in the sense that the wordplay is to be arranged for the answer. The essential point for indicators of anagram clues is that they show a rearrangement, a disturbance to the natural order or a change to be made. There are very many ways of doing this, some reasonably straightforward but others requiring a stretch of the imagination. For example, words and phrases related to drunkenness and madness have to be taken as involving disturbance so that stoned, pickled, tight, bananas, nuts, crackers and out to lunch could all be misleading ways to indicate an anagram. I am often asked for a comprehensive list but, because there are so many, unfortunately there is no such list, though the Chambers Crossword Dictionary (see here) has a large list of anagram and other indicators. The table that follows on the next page is designed to expand on the various categories of rearrangement by giving a few examples of each overleaf:

TOP TIP - ANAGRAMS

Early crosswords did not indicate an anagram; solvers were required to guess that a mixture of letters was needed. This is universally regarded as unfair on the solver so that there will always nowadays be an indication of an anagram.

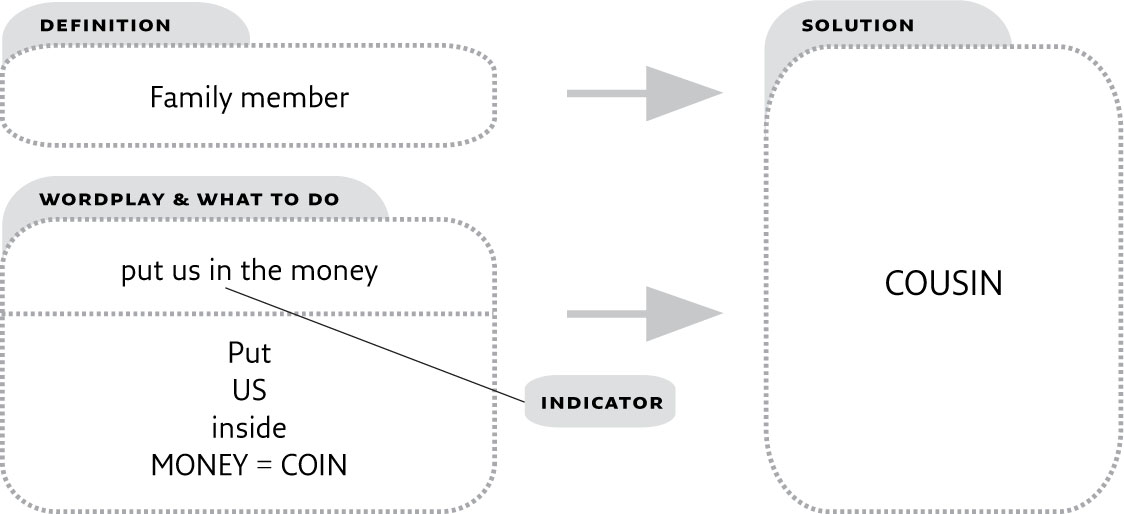

2. The sandwich clue

A sandwich can be considered as bread outside some filling. Similarly in this clue type, the solution can be built from one part either being put outside another part or put inside another part.

This is an example of outside (with an abbreviation to be made in wordplay):

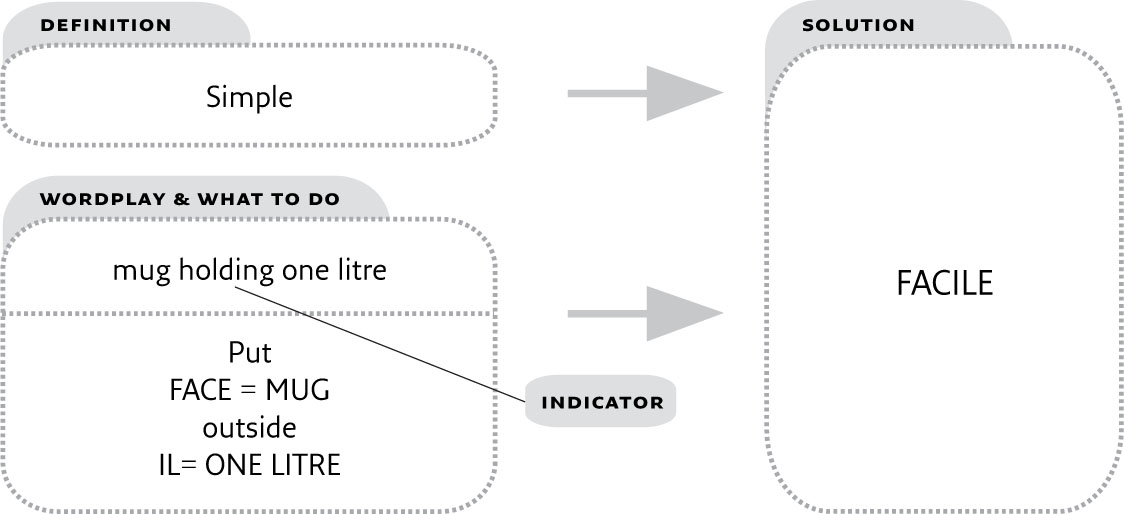

SANDWICH CLUE: Simple mug holding one litre (6)

This is an example of inside with a clear instruction as to what’s to be done:

SANDWICH CLUE: Family member put us in the money (6)

Note that about has multiple uses in crosswords (see Chapter 10).

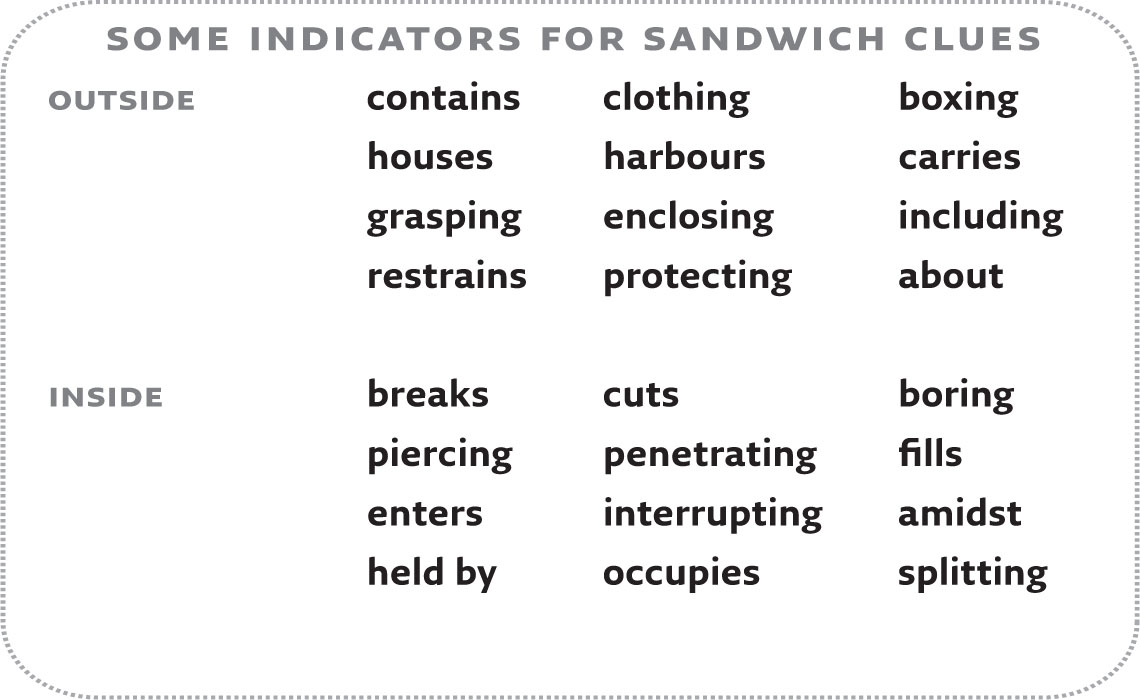

3. The homophone clue

In this type, the solution sounds like another word given by the wordplay. The clue is often fairly easy to recognize but it may be harder to find the two words which sound alike.

HOMOPHONE CLUE: The Speaker’s feeble for seven days (4)

Indicators for homophone clues:

Anything which gives an impression of sounding like another word such as so to speak, we hear, it’s said acts as an indicator. This extends to what’s heard in different real-life situations; for example, at home it could be on the radio; in the theatre it could be to an audience; in the office it could be for an auditor.

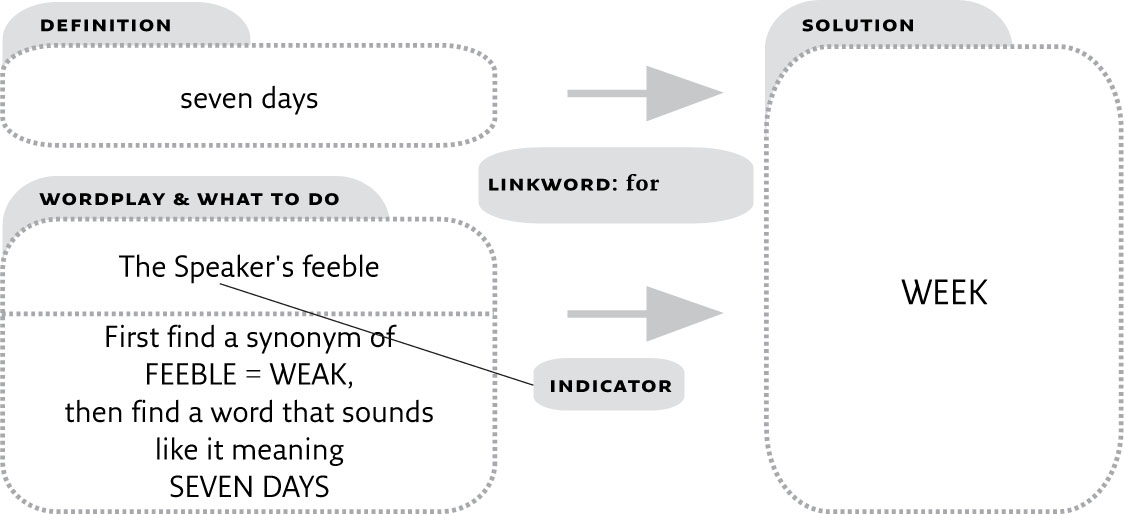

4. The hidden clue

A hidden clue is arguably the easiest type to solve. That’s because the letters to be uncovered require no change: they just need to be dug out of the sentence designed to conceal them. In the first example, the indicator is inside:

HIDDEN CLUE: Parched inside Kalahari desert (4)

Indicators for hidden clues:

Commonly some (in the sense of a certain part of what follows), some of, partly, are unique to hidden clues; within, amidst, holding and in can be either hidden or sandwich indicators.

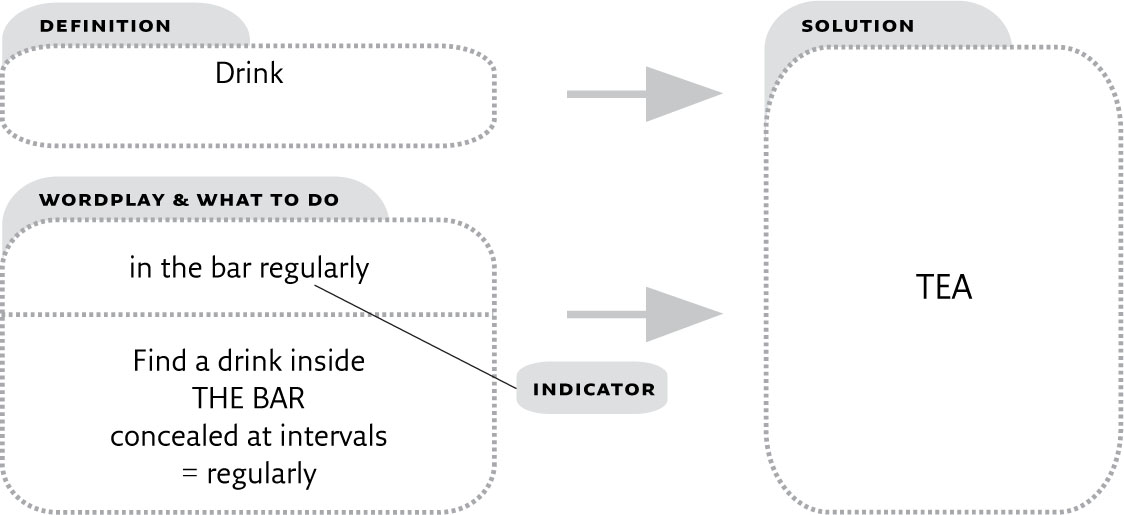

A variant of the hidden clue is where the letters are concealed at intervals within the wordplay, most commonly odd or even letters. You are asked to extract letters that appear as, say, the first, third and fifth letters in the wordplay section of the clue sentence and ignore the intervening letters. Note that there will never be superfluous words in such a clue sentence, making it easier to be certain which letters are involved in the extraction.

Here is one such clue in which you have to take only the odd letters of the bar for the solution.

HIDDEN CLUE: Drink in the bar regularly (3)

Some other indicators for hidden-at-intervals clues:

Oddly, evenly, ignoring the odds, alternately.

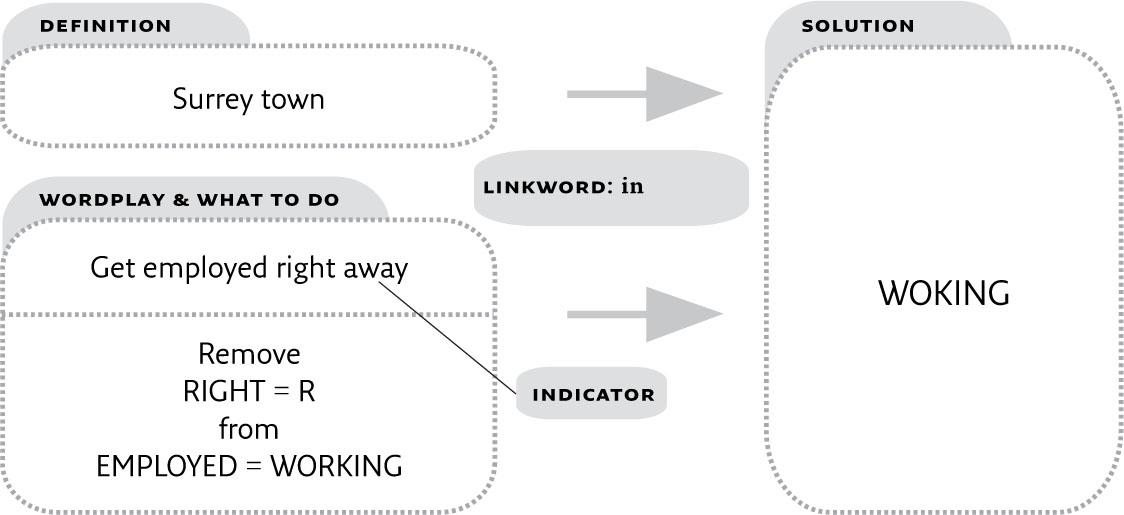

5. The takeaway clue

A takeaway clue involves something being deducted from something else. This can be one or more letters or a whole word. In the example below it’s one letter, R, which is an abbreviation of right, and get is an instruction to the solver. It should be noted that sometimes you will find abbreviations signposted, e.g. “a small street”, more usually not, e.g. “street”. You will find in the Appendices a list of those most frequently appearing in crosswords and all of those used in the clues and puzzles of this book.

TAKEAWAY CLUE: Get employed right away in Surrey town (6)

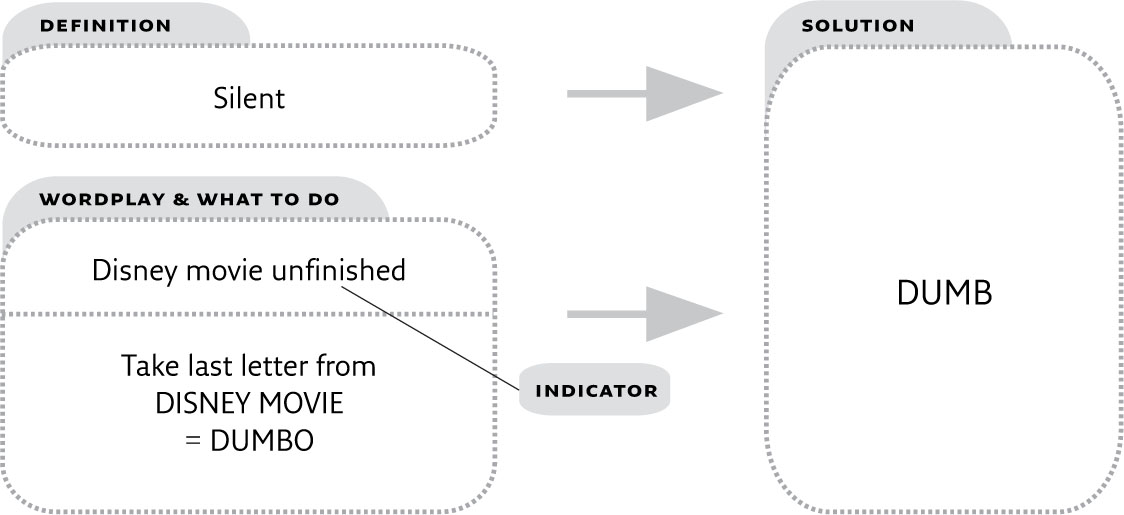

In our second example, it’s the last letter that is to be taken away to leave the solution:

TAKEAWAY CLUE: Silent Disney movie unfinished (4)

Indicators for takeaway clues:

These tend to be self-explanatory, such as reduced, less, extracted, but, beware, they can be highly misleading, such as cast in a clue concerning the theatre, or shed in one ostensibly about the garden. Some indicators inform us that a single letter is to be taken away. These include short, almost, briefly, nearly and most of, all signifying by long-established convention that the final letter of a word is to be removed. There is more on takeaway indicators such as unopened, disheartened, needing no introduction and endless on here, which deal with letter selection indicators.

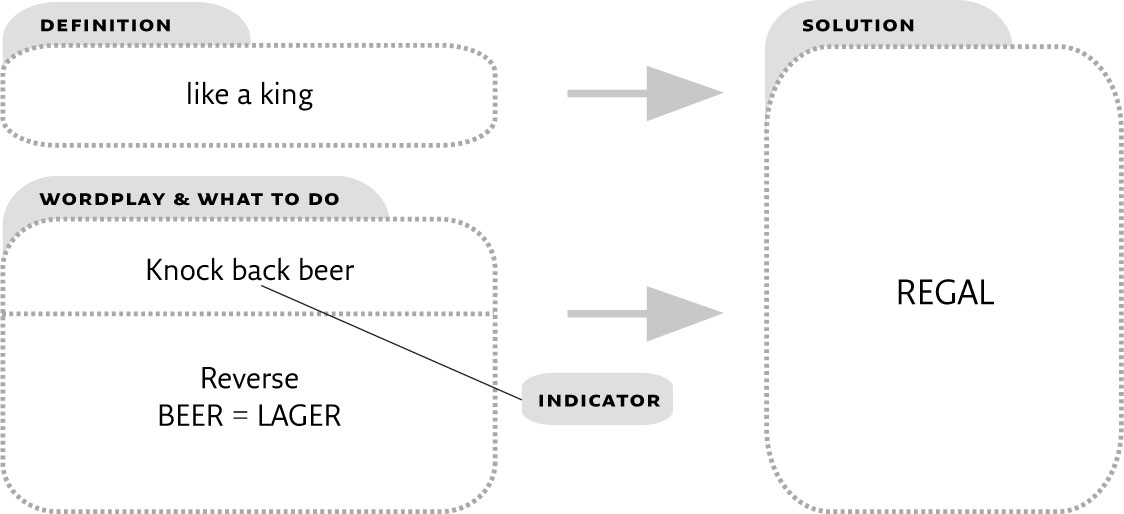

6. The reversal clue

The whole of a solution can sometimes be reversed to form another entirely different word. In addition, writing some letters backwards or upwards is often part of a clue’s wordplay, but for the time being we are concerned with reversal providing the whole of the answer. This is a clue for an across solution:

REVERSAL CLUE: Knock back beer like a king (5)

This is a reversal clue for a down solution (see below for an explanation of why this matters):

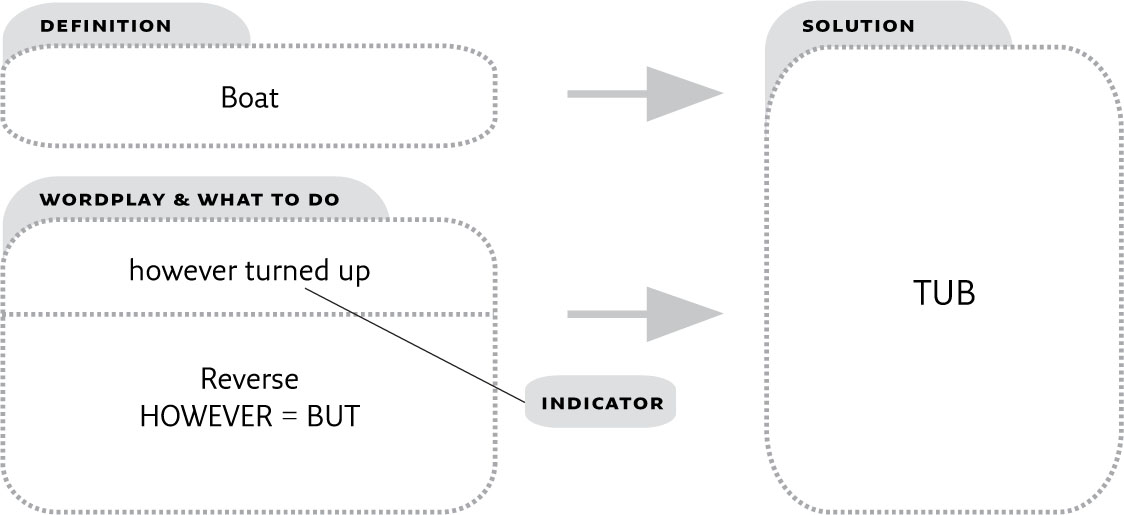

REVERSAL CLUE (DOWN): Boat however turned up (3)

Indicators for reversal clues:

Anything showing backward movement, e.g. around, over, back, recalled.

Do be aware that some reversal indicators apply to down clues only, reflecting their position in the grid. The example above of a down clue uses turned up for this purpose; other possibilities are overturned, raised, up, on the way up and served up.

7. The letter switch clue

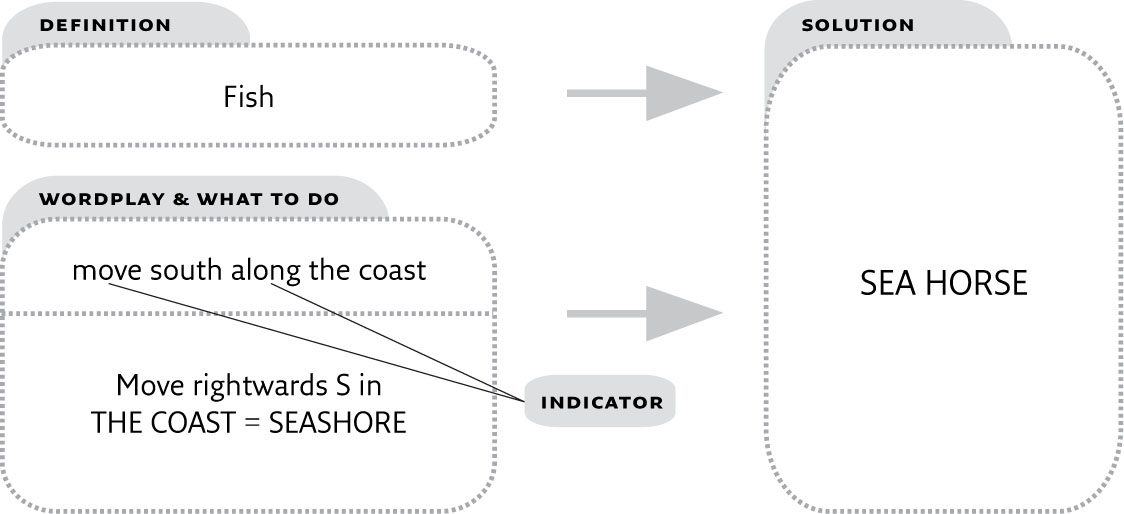

Where two words differ from each other by one or more letters, this can be exploited by setters so that moving one or more letters produces another word, the solution. Here is an example in which you are instructed to shift S for South along a word meaning coast to produce a fish. You are not told which of the two s’s is to be moved but trial and error will eventually show it’s the second.

An extra point to be brought out here is that if a pause or comma after the first word is imagined, the instruction should become clearer. This imaginary punctuation effect is common to many crossword clues; see Chapter 4, here, for more on this point.

LETTER SWITCH CLUE: : Fish move south along the coast (3,5)

There is also a form of letter switch in which letters are replaced rather than moved; see Chapter 8, here, for more on this.

8. The all-in-one clue

In many crossword circles this is also known as & lit. However, I have found my workshop participants usually consider this too cryptic a name! It actually means “and is literally so” but people tend to puzzle over that at the expense of understanding the concept.

In fact, it is a simple one that I prefer to call all-in-one, which is what it is: the definition and wordplay are combined into one, often shortish sentence which, when decoded, leads to a description of the solution.

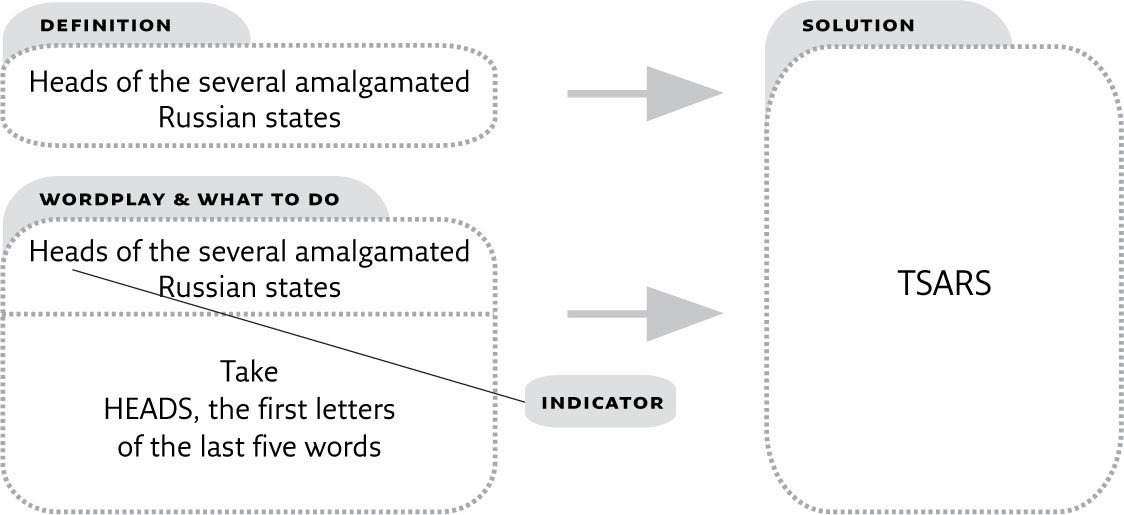

ALL-IN-ONE CLUE: Heads of the several amalgamated Russian states (5)

This clue relies on the letter selection indicator heads (see here) to provide the solution. Most of the clueing techniques outlined earlier can be used to make an all-in-one clue (see examples in Chapter 8, here), always provided that the definition and wordplay are one and the same.

Probably the commonest type is an all-in-one anagram, with an anagram as part or all of the wordplay and no extra definition needed because it has been provided by the wordplay. Here is an example:

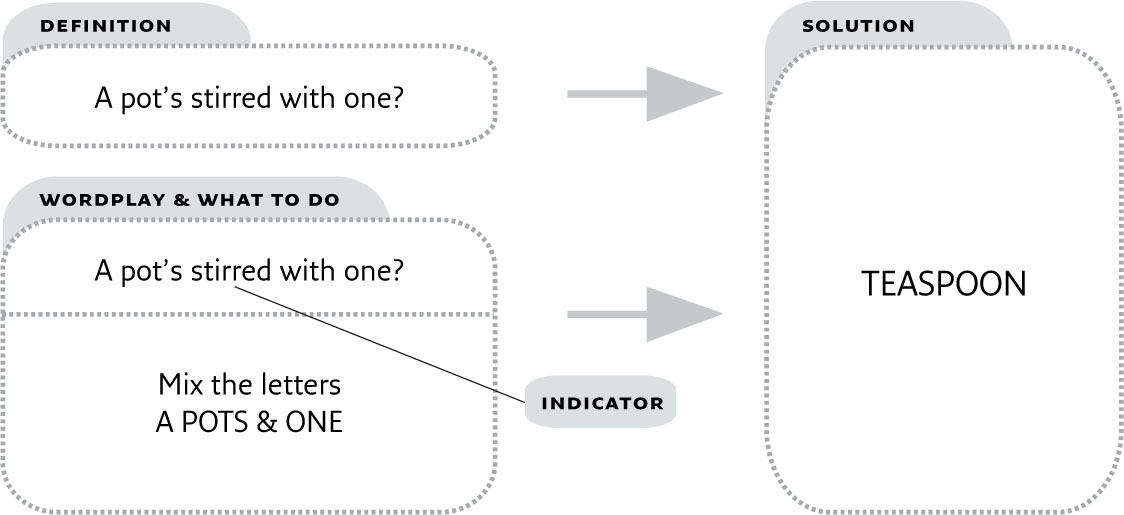

ALL-IN-ONE ANAGRAM CLUE: A pot’s stirred with one? (8)

Incidentally, this clue demonstrates how punctuation can give you some help with a clue. The question mark is telling you that a pot isn’t necessarily stirred with a spoon but it may be. For examples of when punctuation is not so helpful, see Chapter 4, here.

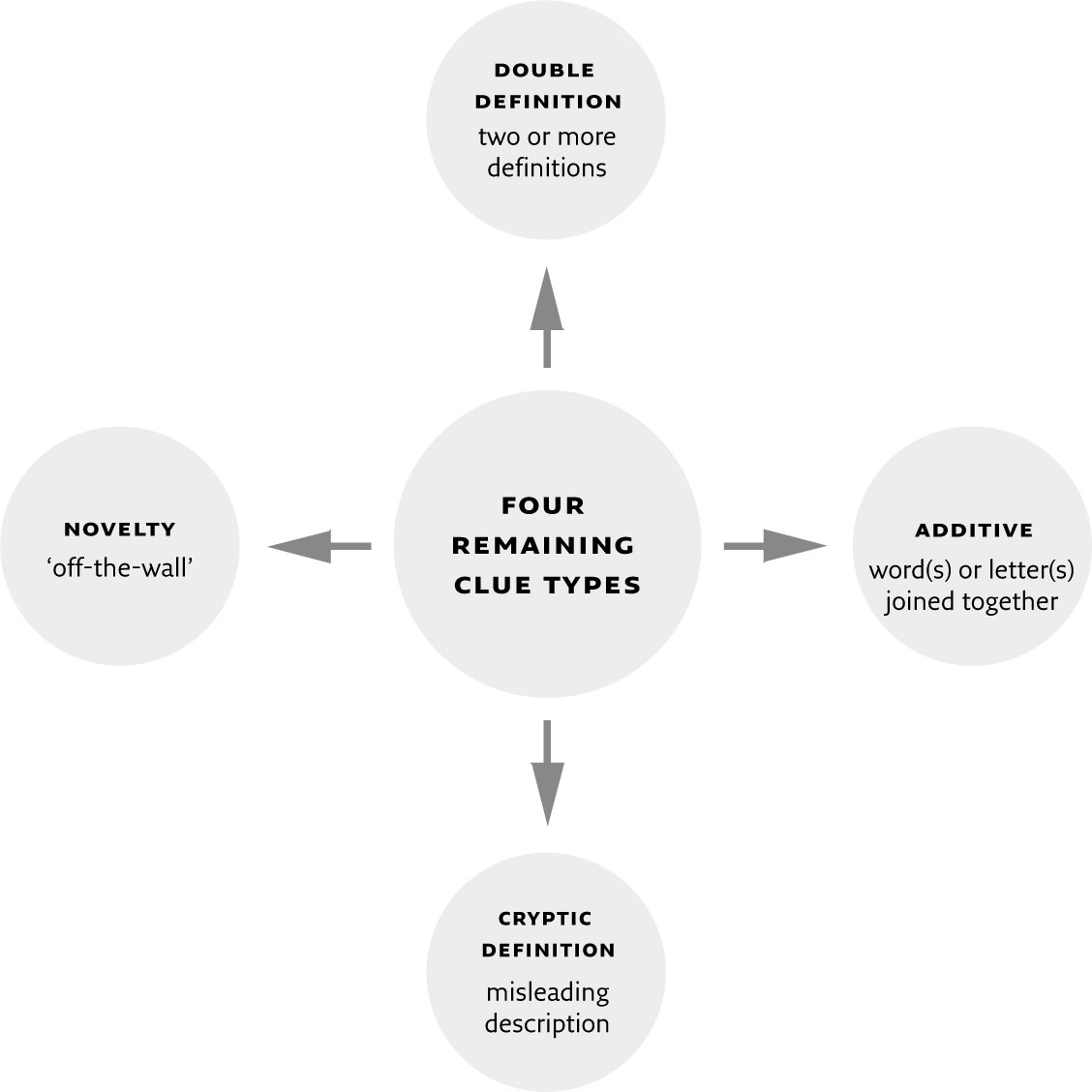

The remaining four types

Now we will focus on the remaining four clue types. Remember that these four only very rarely include indicators within the clue sentence. Here they are together in one chart from which we will proceed to examine each one in turn, starting at the top and going clockwise.

How do we recognize these when no indicator is included?

Punctuation may occasionally be helpful but it’s mainly intelligent guesswork that’s needed. Are these types therefore harder? You can judge for yourself but I’d say not necessarily.

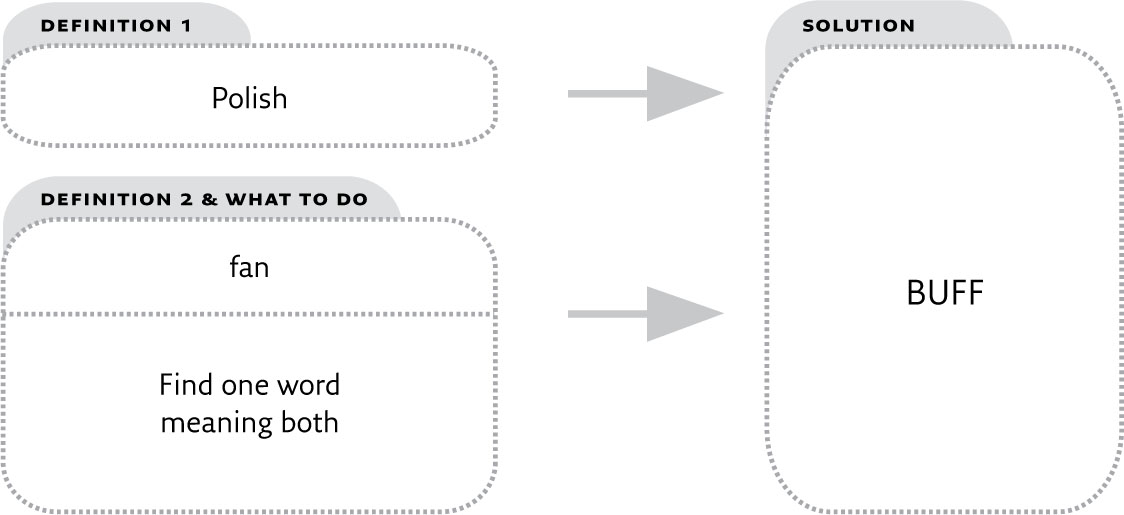

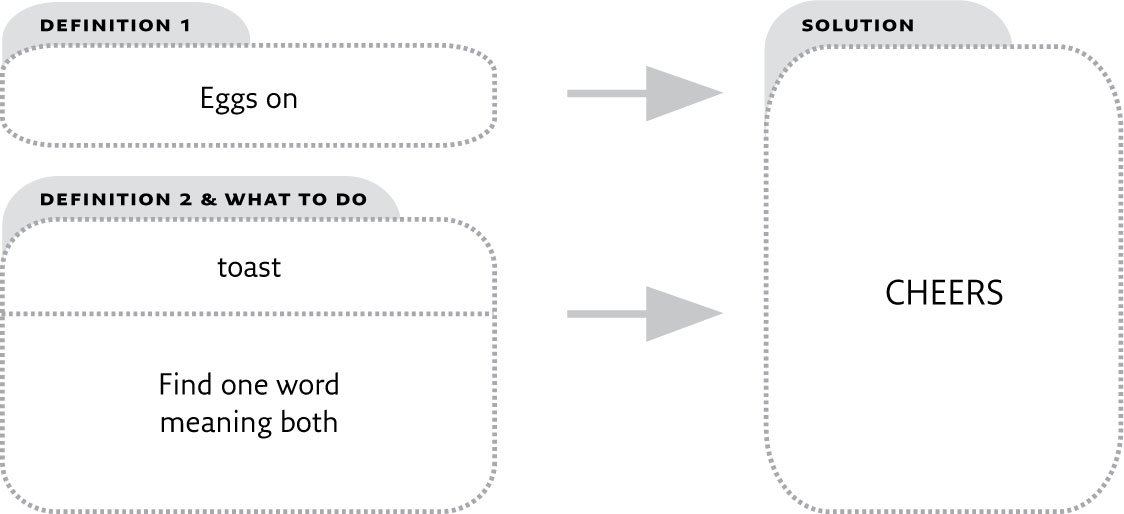

9. The double definition clue

This is simply two, or occasionally more, definitions of the solution side by side. There may be a linking word such as is or ’s, but most frequently there is none, as in this clue.

DOUBLE DEFINITION CLUE: Polish fan (4)

DOUBLE DEFINITION CLUE: Eggs on toast (6)

Indicators for double definition clues:

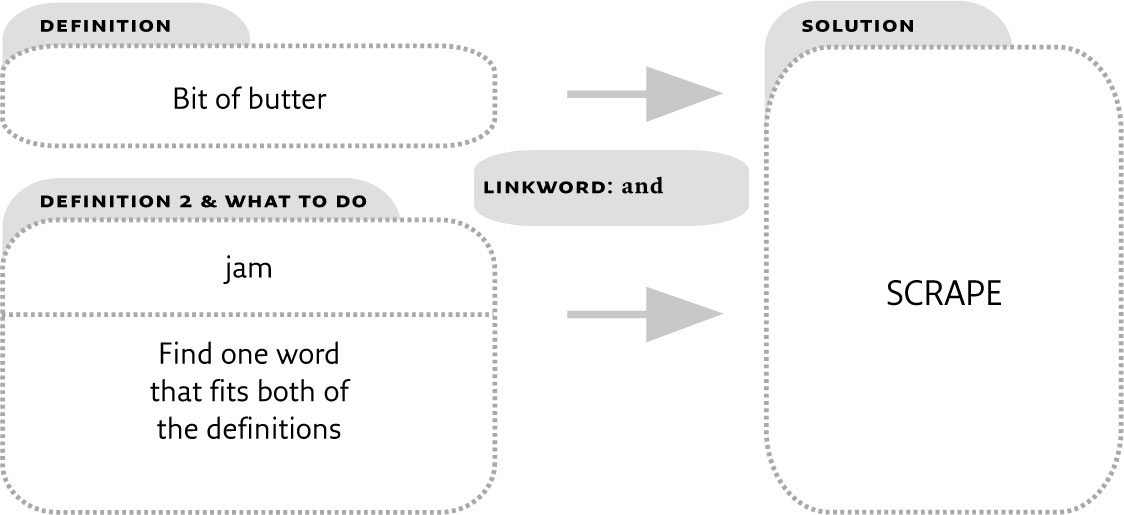

To repeat, though no specific indicator is given the clue type can often be guessed by its shortness. With only two or three words in a clue, there’s a good chance it’s a double definition. One way of spotting this type of clue is an and in a short clue, as in our next example.

DOUBLE DEFINITION CLUE 3: Bit of butter and jam (6)

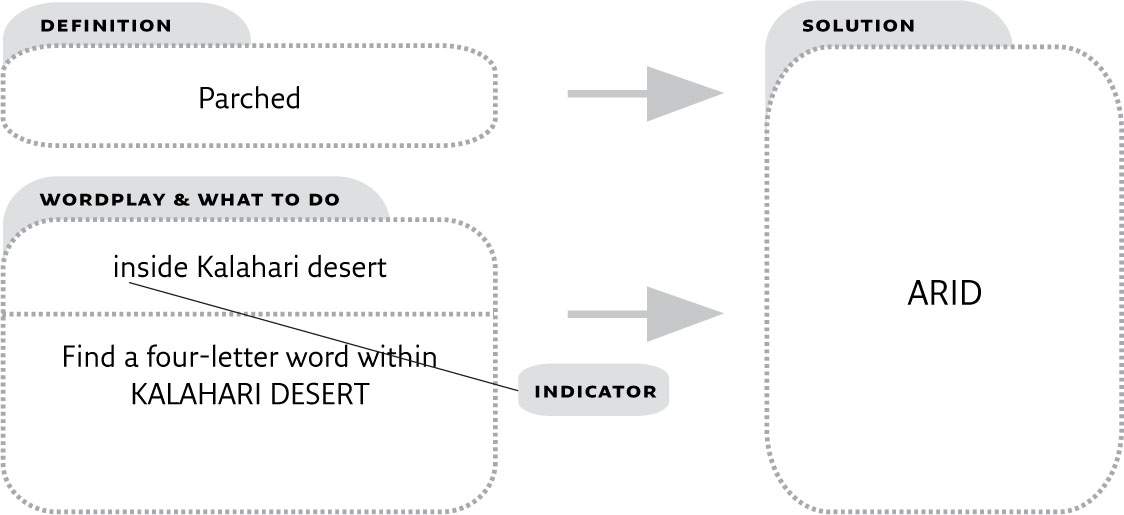

10. The additive clue

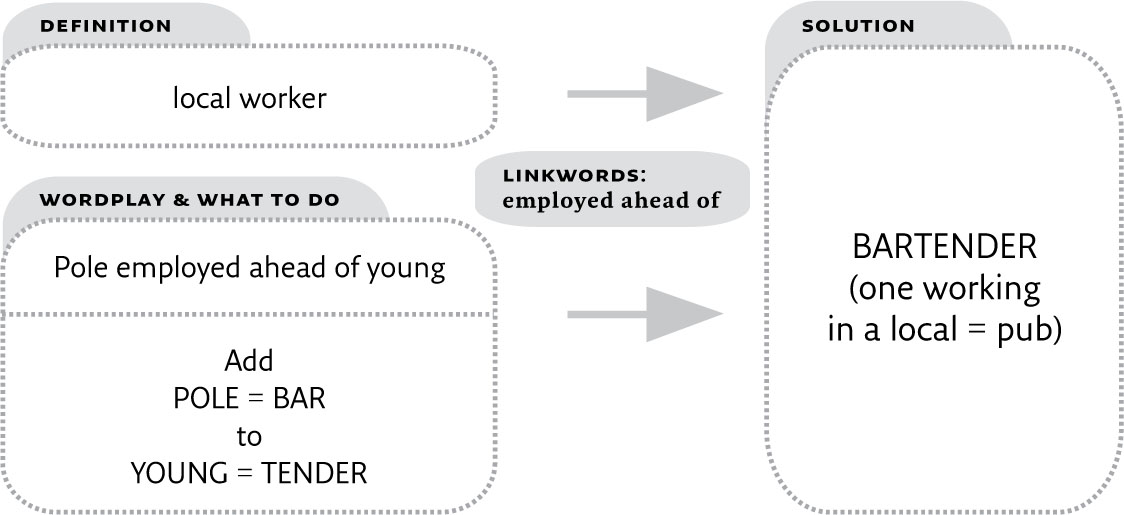

As we saw at the very beginning of this book, an additive clue consists of the solution word being split into parts to form the solution. Sometimes known as a charade (from the game of charades, rather than its more modern meaning of ‘absurd pretence’), it may be helpful to describe it as a simple algebraic expression A + B = solution C. Here is one with several misleading aspects. Note the use of the linking phrase employed ahead of, telling you to join part A to part B:

ADDITIVE CLUE: Pole employed ahead of young local worker (8)

Indicators for additive clues:

With no specific indicator, it’s a question rather of spotting that A + B can give C, the solution. Sometimes, as in above example, this is made easier by linkwords such as facing, alongside, with, next to, indicating that the parts A and B have to be set alongside each other. In the case of down clues, the corresponding linkwords would be on top of, looking down on and similar expressions, thereby reflecting the grid position of letters to be entered.

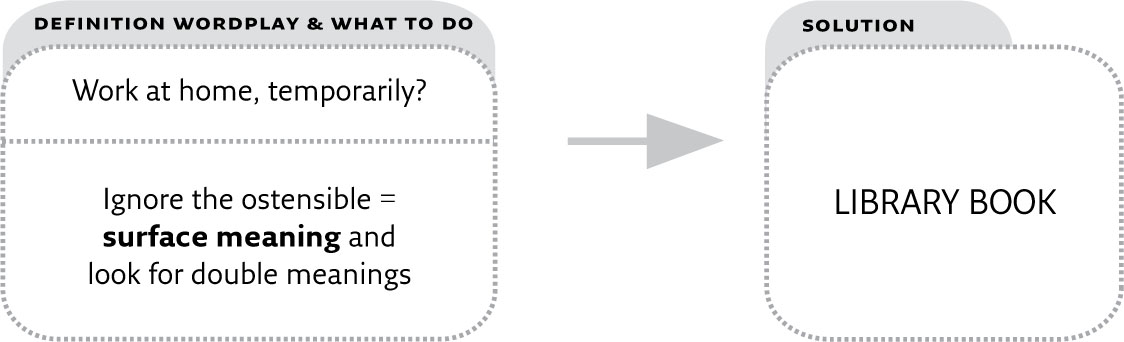

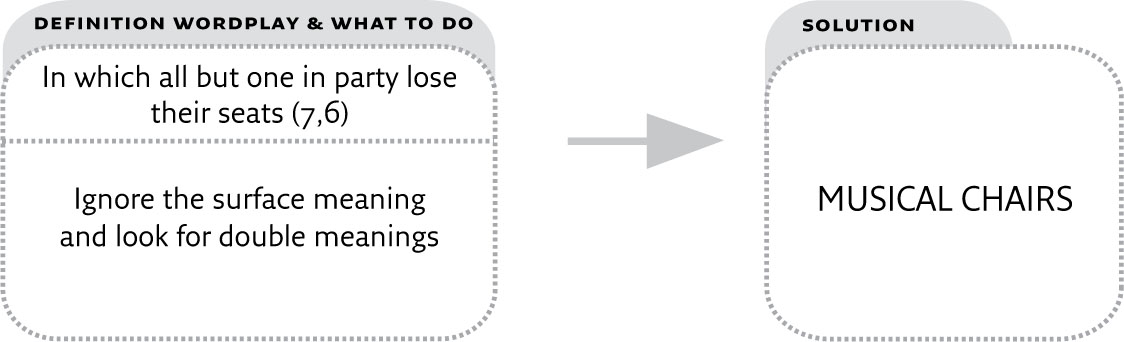

11. The cryptic definition clue

There are no component parts at all to this clue, which consists simply of a misleading, usually one-dimensional, way to describe the solution. Depending on how much information is imparted by the clue, it can be very easy or very tough. The best of these clues have an amusing or whimsical air, as in both these examples:

CRYPTIC DEFINITION CLUE: Work at home temporarily? (7,4)

CRYPTIC DEFINITION CLUE: In which all but one in party lose their seats (7,6)

Indicators for cryptic definitions:

The nature of this clue type is such that no indicator is ever given. It can be identified either from the fact that nothing in the clue looks like an indicator, and/or from the presence of a question mark. A tip is to look hard at words which have more than one meaning and then think below the surface. Otherwise, wait until some intersecting letters are available.

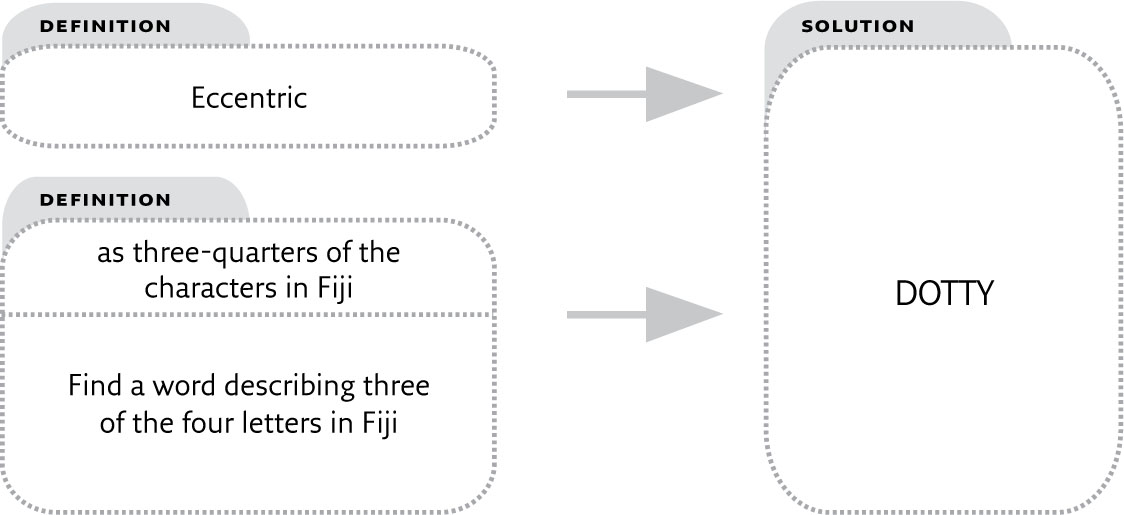

12. The novelty clue

From the inception of crypticity in crosswords, there have been innovative clues conforming to no single pattern which defy categorization into any of the preceding groups. These clues are often solved with extra pleasure.

The setter has found it possible to exploit coincidences or special features of a word. As with the cryptic definition type, the solver is asked to think laterally and throw away any misleading images created by the clue. In some rare circumstances when an especially novel idea is used, there may not even be a proper definition. There are more examples of the novelty clue in Chapter 8 but, as a taster, here is one:

NOVELTY CLUE: Eccentric as three-quarters of the characters in Fiji? (5)

TOP TIP – CLUE FREQUENCY

Given the twelve clue types identified, which are the most commonly found? The answer to this is that frequency patterns vary according to setter and newspaper but that the additive, anagram, cryptic definition and sandwich types are the most common; they may indeed account for more than half the clues in many crosswords. It may help you to know that there are rarely more than two or three of the following types in any one puzzle: hidden, homophone, all-in-one, novelty, letter switch.

Letter selection indicators

Before moving on to solving clues, we have to consider how individual letters within clues are signposted. We have seen what sort of indicators go with what sort of clues; now we’ll take a look at another commonly used indicator which is essential to solving skills. Take this clue as an example:

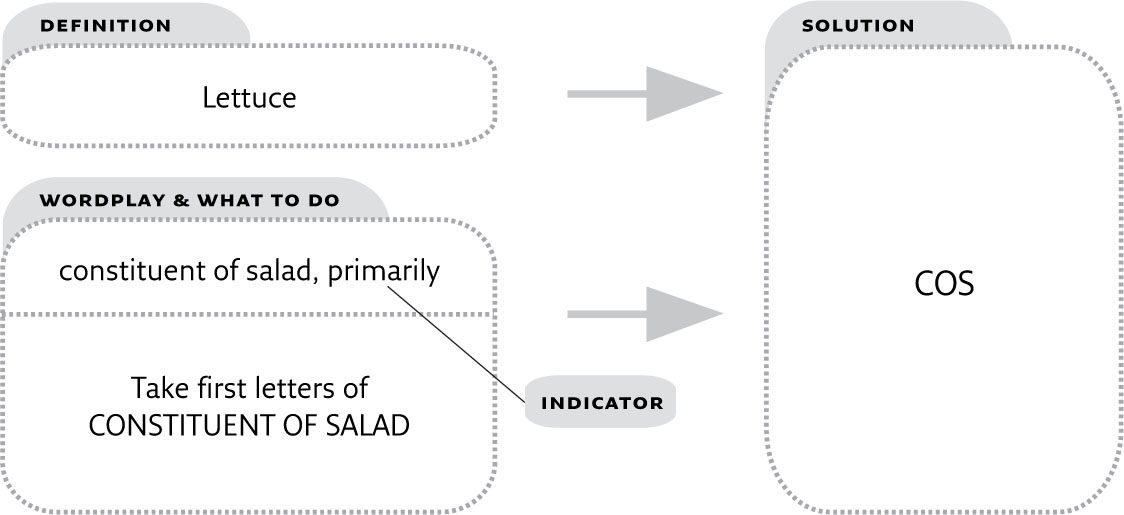

ADDITIVE CLUE: Lettuce constituent of salad, primarily (3)

Experienced solvers would be immediately drawn towards the word primarily as it indicates that the first letter or (as in this case) letters of the preceding words are to be selected as building blocks to the solution. In more complex clues they could then be subject to further treatment, such as forming part of an anagram, but here they are used simply to form cos, the lettuce salad ingredient.

There are many alternative ways of showing that the first letter is to be manipulated in some way. Some of these indicators are: starter, lead, source, opening, top, introduction and so on. They may be extended to the plural form too with the use of, say, beginnings, foremost and heads. Note that bit of, part of and suchlike by long-standing convention always indicate the first letter.

Other positions within words are indicated in a similar fashion. The last letter can be end, back, finally, tail and the middle letter centre, heart, and all of the inside letters of a word can be innards, contents, stuffing.

In their negative takeaway guise, they can be headless, unopened, failing to start; and empty signifies that the whole of the innards of a word is to be removed.

Overleaf are some examples of letter selection indicators at work:

TAKEAWAY CLUE: Endless industrial action in a Scandinavian port (4)

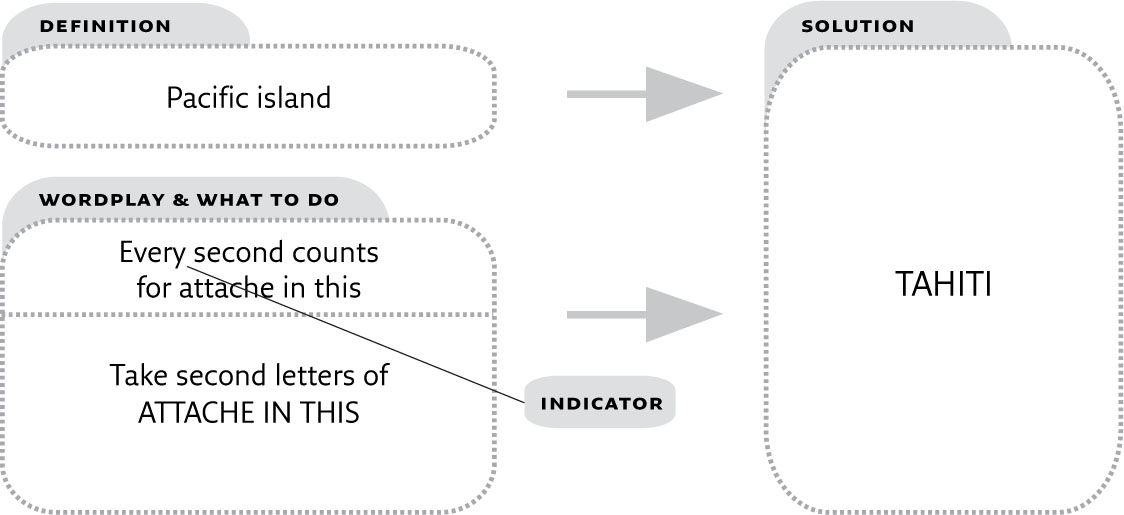

ADDITIVE CLUE: Every second counts for attaché in this Pacific island (6)

After a time, you will become familiar with looking beyond and through the surface meaning of a word doing duty as an indicator so that you realise what you are required to do to the relevant letter(s) or word(s).

TOP TIP – LETTER SELECTION INDICATORS

Beware letter selection indicators that, depending on the setter’s policy, can do double or triple duty:

Endless: take away last letter only, or first and last letters.

Head: first letter, or take away first letter (in its sense of behead).

Cut: last letter takeaway, sandwich (inside type), anagram (in its slang sense of drunk).

Back: last letter, reversal.

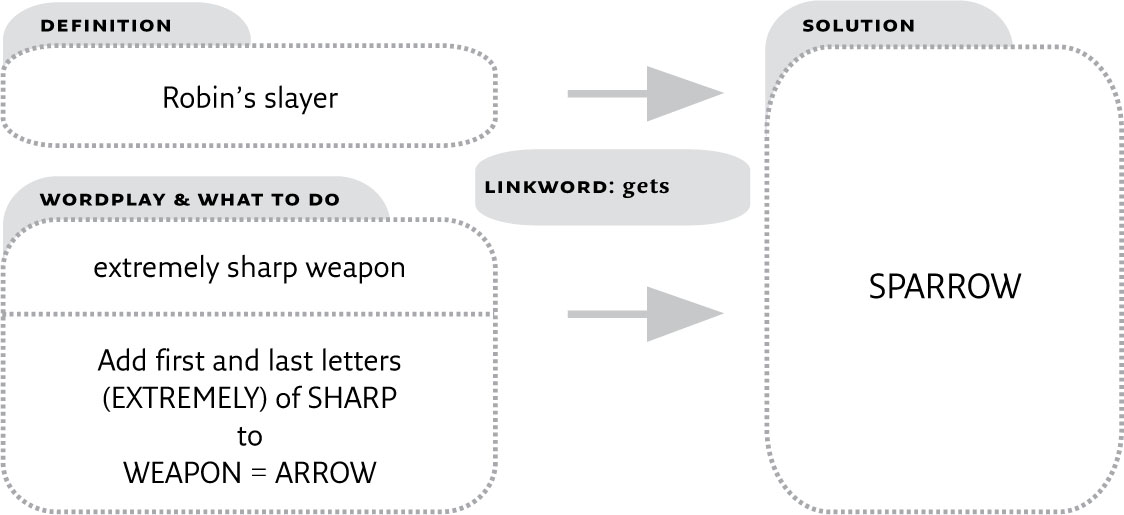

Note that in the example below extremely indicates first and last letters; in some crosswords it can indicate the last letter only of the preceding word.

ADDITIVE CLUE: Robin’s slayer gets extremely sharp weapon (7)

There are examples of indicators throughout this book but it would take an impossibly large volume to include all those used. There are books which list more (as covered in Chapter 12) but even they are not comprehensive. The point to bear in mind is that once you are aware of the possible clue types, you will often be able to infer from a word or words what you are being instructed to do.