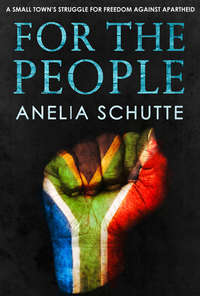

For The People

There, like his father before him, the boy climbed trees, played in the forest and ate wild berries.

Even today, says Ronnie, his son still talks about that day he took him to Concordia, and showed him the life he’d left behind.

Chapter 7

Xenophobia

In my second week back in Knysna, my parents take me to lunch at Crab’s Creek, a pub on the edge of the lagoon. While we wait for the pretty black waitress to bring us our drinks, my mother says hello to a coloured lady she recognises at the table behind us. I’m introduced as the daughter who’s been living in London and the coloured lady says her daughter is overseas too.

At another table, three teenage boys are drinking bottles of Castle lager. Two of them are coloured, one is white.

So much has changed since I was their age.

There were only a handful of non-white children at Knysna High when I finished school in 1995. One of them was black, a girl in my class. In a year below me there was a coloured boy, a talented rugby player. The only others, if I remember correctly, were two younger Indian boys. They were some of the first Indian people I’d ever encountered, as most of South Africa’s Indian population was concentrated in the Natal province on the eastern coast of South Africa, where I’d never been.

It was only the year after, when I went to study in Cape Town, that I made my first black, coloured and Indian friends in an advertising college that was still predominantly white.

Back at my parents’ house, our stomachs full of pub lunch, my father and I settle down to watch TV. As my father pokes his dowel at the buttons to skip through the channels, South Africa’s new racial integration flashes before me. Mixed-race pairs of South African DJs, comedians and equestrian stars do the cha-cha on Strictly Come Dancing. In one of the locally produced soap operas, black actors speak Afrikaans one minute and English or Zulu the next. Another soap is entirely in Zulu, with English subtitles.

When I was little, we had one channel on SABC TV that broadcast only in English and Afrikaans. American shows like Buck Rogers and T. J. Hooker were dubbed into Afrikaans, with the English soundtrack broadcast simultaneously on the radio. On two separate channels, there was ‘black’ programming in African languages.

My father finds the news he was looking for and puts down the dowel.

In stark contrast to Strictly Come Dancing and the soaps, I now see the other extreme of the new South Africa: a report on recent forced removals in Johannesburg. In one incident outside a church, police grab black people, including women and children, off the streets, beating them if they don’t comply. I could be watching a scene twenty, thirty years ago. But unlike thirty years ago, those people aren’t being removed because they’re black. They’re being removed because they’re illegal immigrants from Zimbabwe who were sleeping on the street because the homeless shelter in the church was full. And unlike thirty years ago, the policemen who are beating them are also black.

When the news is over, my father goes back to poking at the TV. On one of the channels he flicks through, the same story from Johannesburg is repeated, this time in Xhosa.

I’ve been hearing and reading a lot about xenophobia in South Africa since I’ve been back here. In Knysna, black people complain about Zimbabweans, Somalis and Nigerians coming into the townships, bringing with them drugs and violence while taking jobs, houses and women. White people complain their taxes are being spent on giving those illegal immigrants special treatment. Coloured people complain they’ve been forgotten.

From what I’ve heard, it’s the black people who are most xenophobic. And in Knysna, the tension between locals and immigrants, or ‘newcomers’, has led to clashes in the townships at least once in the past year.

The stories I’ve heard from various people in town are confirmed by reports on national newspapers’ websites. During what was called South Africa’s ‘xenophobic unrest’ in 2008, several Somali-run shops in Knysna’s townships were looted and their owners driven out of the community. Over a hundred foreign nationals from Somalia and other African countries fled the townships and sought refuge at the police station. Teachers at the local schools were told not to send any foreign children back to the townships. For months, the foreigners had to stay in tents on the rugby and hockey fields at Knysna’s sports park until it was safe to return to their homes.

It seems there’s still tension in Knysna now.

One of the main stories in the Knysna-Plett Herald these last few weeks has been about a group of African traders who’ve been removed from their long-established roadside market by the Knysna Municipality. The reason for it wasn’t xenophobia – the municipality was planning to widen that stretch of road and the traders were in the way. But the public response to the money spent moving the traders – to a new site with pre-built market stalls, toilets and twenty-four-hour security – has had definite xenophobic overtones.

It’s not that the traders are ‘newcomers’ – many of them came from Zimbabwe and Nigeria as far back as ten, fifteen years ago. But in many people’s eyes they’re still nothing more than illegal immigrants.

According to one angry letter in the Herald, ‘These illegals are not “previously disadvantaged”. They come to our country of their own free will and are now using us. They are opportunists and should be treated as such.’

This xenophobic attitude seems to be common in the new South Africa, but it’s news to me. It has never made the headlines in the UK and my mother, who’s always quick to phone me when a family friend has died or there’s been some or other scandal in the government, has never mentioned it either.

So when my mother invites me on a diversity training course organised by her work, I go along in the hope that it will shed some light on xenophobia and how South Africans are being advised to deal with it.

The course is held at a home for the aged in Hornlee where we have a large, cold room to ourselves. There are fifteen people taking part, most of them employees at Epilepsy South Africa, plus a handful from other charitable organisations in neighbouring towns.

The course-leader, a man called Ismaiyili from somewhere in North Africa, divides us into groups, deliberately mixing white, black, coloured, English, Afrikaans, Xhosa, young, old, male and female. I’m separated from my mother and end up in a group with a black man, two black women and two coloured women.

From the start, xenophobia features high on the agenda – as high as the first page of the handbook we’re given, where it says that a recent report on migration in South Africa showed that ‘the practice of xenophobia by South Africans is amongst the highest in the world’.

Ismaiyili asks us to discuss, in our groups, whether foreigners should be allowed to set up a business or get a job in South Africa.

Within our group, there’s a barrier to our communication: the older of the coloured women speaks only Afrikaans. And the younger of the black men refuses to speak anything other than English. I end up translating for the coloured woman’s benefit.

When I was growing up, it was mandatory for white children to study both English and Afrikaans at school.

Having established in our group that by ‘foreigners’ we mean Zimbabweans, Nigerians, Somalis and Mozambicans, my three black team-mates insist that those foreigners shouldn’t be allowed to work in South Africa at all.

‘They come here and they take our jobs,’ says one.

‘And they’re cheap labour,’ says another. ‘We can’t compete.’

I try to be impartial and tell them how the same could be said of me going to London and working there.

They don’t seem convinced, but eventually my black team-mates concede that it’s OK for foreigners to start businesses in South Africa, but only if they give South Africans jobs. The coloured people agree.

The rest of the day deals with more general diversity in the workplace. Some of the most surprising moments come when the older black and coloured delegates share their stories of apartheid and how they were treated ‘back in the day’.

The most junior delegates, about ten, twelve years younger than me, are amazed and amused at the stories of a world that seems foreign to them. And yet they fail to see the parallels with their own attitudes towards their Zimbabwean, Nigerian, Somali and Mozambican neighbours.

The next day, I take my research to the library and the Internet, where I scour news reports, articles and readers’ letters on the subject.

Unemployment seems to be one of the main reasons behind the xenophobia. Black South African workers are more aware of their rights than ever, and unions are quick to stage walkouts over pay. The illegal immigrants, on the other hand, work cheaply. And they work hard.

Housing is another issue. For years, the government has been building identical simple brick houses in townships across South Africa as part of its Reconstruction and Development Programme, or RDP. The houses are meant solely for South Africans, but some foreign nationals from neighbouring countries have found their way into them, usually by renting them off cash-strapped South Africans who are willing to go back to living in a shack in their own back yard if it means earning some extra money.

I’ve heard that some RDP homeowners have even ‘sold’ their houses in unofficial transactions for as little as a month’s wages. I wonder whether they realise they’ve blown their one chance to get a house from the government.

The black families who are still waiting for their houses in Knysna’s townships after fifteen years of promises from the ANC government are understandably angry when they see the Zimbabweans and Nigerians moving in.

It’s hard to believe that, less than forty years ago, there were hardly any black people here.

Chapter 8

1972

Owéna hadn’t come across many black people in her life. Growing up in the Western Cape, the non-white people she encountered were mostly coloured. That was because the government had declared the entire region a ‘coloured labour preference area’, meaning that, by law, manual and semi-skilled jobs were to go to coloured people over black.

If a black person wanted to try their luck getting a job in the Western Cape, or indeed anywhere in South Africa, they also had the pass laws to contend with.

The pass laws were part of the apartheid government’s plan to restrict the influx of black people into ‘white’ South Africa from the African homelands. Created by the National Party government in the 1950s, the homelands were ten regions within South Africa’s borders where the different black tribes were meant to live, develop and work among their own. Despite black South Africans outnumbering white by around eight to one, the ten homelands together made up just thirteen per cent of the country’s land.

Encouraged by the government, several of the homelands became self-governing, quasi-independent states in 1959.

In 1970, a law was passed that made all black South Africans citizens of their homelands and no longer of South Africa, removing their right to vote and making white people the new majority.

If any black person wanted to travel outside the borders of their homeland, they had to carry a passbook at all times. And if they wanted to live and work in a South African town or city, they needed one of two things in their passbook: either a so-called ‘section 10’ stamp, or a temporary work permit.

The section 10 stamp gave the bearer of the passbook permission to live somewhere permanently, usually because they were born there. To live and work anywhere else, they needed a work permit that had to be renewed every year. An employer had to apply for that permit on behalf of a worker, so that no black person could move between towns and cities without having a guaranteed job at their destination. The work permit usually covered only the worker, not his wife or children, who had to stay behind. Anyone caught without the necessary paperwork was evicted and sent back to where they came from – a job that fell to the Bantu Affairs Administration Board.

Formed in 1972, Bantu Administration, as most people called it even after its name changed a number of times, was the government department responsible for the ‘development and administration’ of South Africa’s black population. As an enforcer of apartheid, the Administration was despised by the black people and in this context, the word ‘bantu’ – Zulu for ‘people’ – became offensive by association.

The government’s influx control meant Knysna, like the rest of the Western Cape, didn’t have much of a black population in 1972.

The few black people in Knysna – those who had been born and raised in the area and so had the necessary section 10 stamp to stay there – lived among the coloured people in places like Salt River until they were evicted along with their coloured neighbours.

But the black people couldn’t go to Hornlee with its schools and its churches and its community centres and sports fields. Because, under the Group Areas Act, black and coloured couldn’t mix.

With no township of their own to go to, they ended up squatting in shacks in the hills around town, on land that was undeclared for any particular colour.

In a desperate attempt to give their families a better life, many black people attempted to get into Bigai by pretending to be coloured, even changing their surnames to sound less African.

The authorities had various tests and techniques to catch out those imposters. One was to check whether the person could speak Afrikaans, as most coloured people spoke it as their first language. A black man from the Transkei, the official Xhosa homeland, would never have had the opportunity to learn the language, and so would be exposed as ‘acting coloured’ if he failed to answer a question in Afrikaans. Alternatively, a policeman might ask that black man to say ‘Ag-en-tagtig klein sakkies aartappeltjies’, an Afrikaans phrase that simply meant ‘eighty-eight small bags of potatoes’, but had so many guttural sounds and inflections completely alien to the African tongue that few Xhosa people could pronounce it.

Fortunately, many of the Xhosa people native to Knysna spoke fluent Afrikaans, having grown up among the coloured community. And so there were some of them who passed the language test and made it into Hornlee.

Those who didn’t returned to the squatter camps.

Whereas the Western Cape had no black population to speak of, it was a very different story in the neighbouring Eastern Cape.

With no coloured labour preference and a border shared with the poverty-stricken Transkei homeland, the Eastern Cape was a popular destination for migrant Xhosa workers looking to feed their starving families. Once there, they worked in factories and on farms, in gardens and on building sites, anything they could get to be able to send some money back home.

But the black workers far outnumbered the available jobs in the Eastern Cape. Desperate for money, many of them turned their attention to the Western Cape. And when they heard rumours of job opportunities in Knysna’s sawmills and furniture factories, one black man after another took his chances and moved there, work permit or not.

From towns and cities like Umtata and East London, they hitchhiked to Knysna, a long and arduous journey often undertaken on the back of a Toyota or Isuzu bakkie, the pick-ups popular with South Africans and especially farmers.

Those people with work permits were often put up in compounds on their employers’ premises. Those without permits, however, had no choice but to join the squatters in the hills, where they lived in fear of getting caught.

The Bantu Administration van was a familiar and feared sight in the squatter camps. Raids were common, often at three, four in the morning in an effort to catch people while they were sleeping.

But word spread quickly, and the ‘illegals’ were good at hiding.

Chapter 9

Jack and Piet

As a white child in Knysna, I knew nothing of the Bantu Administration or its work. So it comes as news to me that one man who used to work for the Administration is someone I know.

Piet van Eeden’s family went to the same church as mine, and his daughters were just a few years ahead of me at school.

My parents tell me there’s another ex-employee of the Bantu Administration who’s still in Knysna. His identity is even more surprising than Piet’s, not because I know him – I don’t – but because he’s black.

Neither of them is hard to track down. Piet van Eeden now manages a supermarket near my parents’ house, and his black ex-colleague Jack Matjolweni is working at the Department of Labour.

I call Jack at work, introducing myself by my married name. At first he sounds guarded, but when I explain who my parents are, he’s more forthcoming.

‘Aaaah, I know your mother,’ he says. I can hear he’s smiling now. ‘And I know your father very well.’

My father often deals with Jack to sort out benefits for Johnny, our gardener.

Jack says he’ll come to my parents’ house after work.

I’ve heard of Jack. In the last week I’ve had a few conversations with people from the townships and Jack’s name came up often – and never in a favourable light. It’s not surprising. A black man who worked for the apartheid government and raided his own people’s houses to catch women’s husbands and boyfriends and send them away couldn’t have been popular.

One woman I spoke to put it down to the attitude with which Jack did his job. He was young and full of spirit, she said. He was just too keen.

Jack is all smiles when my father opens the door. He’s tall, so tall he has to bend over slightly to get through the door between the kitchen and the dining room. He looks much younger than his fifty years in a leather jacket and khaki chinos that make him resemble a black Indiana Jones.

Jack speaks Afrikaans to my father but switches to English when he speaks to me. It seems more natural that way, as we spoke English on the phone. His English is broken with a strong African accent and he throws in the odd Afrikaans word here and there.

I offer Jack a coffee, tea, maybe a beer. Just hot water, he says. With sugar. I bring him his drink with a bowl of freshly baked rusks.

Jack laughs when he remembers the past. He has a high-pitched giggle that doesn’t go with his face or his size, and I find myself warming to him. It’s not that he’s making light of history by laughing about it, rather that he can hardly believe his own stories of how things used to be.

Jack tells me he was still at school when he started working for the Bantu Administration. He was seventeen.

He was recruited by chance in 1976 while he was waiting in line in a Bantu Administration office. Born in Humansdorp in the Eastern Cape, he needed a stamp in his passbook for permission to go to school in a nearby town. While Jack’s papers were being processed, one of the white Bantu Administration officials came to him and offered him a job. ‘He came to me and said “Hey, I want someone like you,”’ says Jack.

By ‘someone like you’, the man meant a black boy who could speak Xhosa, Afrikaans and English, and was still young enough to be trained and shaped into whatever the Bantu Administration wanted him to be.

Jack says the fact that he was only seventeen and still at school didn’t seem to faze his prospective employer.

‘He said I could go to night school and finish my studies that way.’

Jack accepted the job. It was just too attractive an offer to refuse. Being a Bantu Administration employee meant he no longer needed permits in his passbook. It also made it relatively easy to transfer to Knysna.

As a Bantu Administration inspector, Jack had to check people’s passbooks and make sure they had the necessary permits to be in Knysna. Sometimes he would go from door to door in the squatter camps looking for ‘illegals’, other times he would get a call or an anonymous letter from someone blowing the whistle on a rival for a job or a girl.

‘What, black people would turn each other in?’ I ask him.

‘Ja!’ he says. Yes.

Sometimes the letters and calls were from coloured workers who’d lost out on a job. Other times they came from white employers, maybe bitter about losing a worker to a competitor who was willing to pay more. But most often the letters and calls were from black people: jealous boyfriends in Knysna who wanted to get back at the men who took their women, or concerned wives in the Transkei who hadn’t heard from their husbands for months.

Jack explains that most black workers left their wives and families behind in the homelands when they came to Knysna, promising to send money as often as they could. But a year was a long time for a man to be away from his wife, and many of the workers took girlfriends in Knysna. Jack remembers wives turning up from the Transkei and the Eastern Cape looking for their husbands. He tells me how those wives would cry when they saw their husbands with other women, often with new children.

‘If somebody came to me saying the husband has left and he’s got kids, then I was fighting for that,’ says Jack. ‘I was not worried about girlfriends and boyfriends. But I was always fighting for married people.’

Not all of the illegals in Knysna were married, however, and some of them fell in love with the local girls. Those men found themselves in a different predicament. Even if they married their Knysna girl, they wouldn’t be allowed to stay without a permit. Should they try to find work without a permit, they increased their chances of getting caught. And should they get caught, they’d be sent away, back to where there was no work to support their new family.

‘What about those women?’ I ask.

‘It made no difference,’ he says. ‘The men had to go back.’

And leave the wife and children behind?

‘The law doesn’t look on that,’ says Jack. ‘That time they would say the wife must go to Transkei.’

I am amazed at his apparent loyalty to his then employer, the apartheid government, and his almost blind acceptance of its laws. But he admits that it simply wasn’t his place to say anything.

‘I was an inspector,’ he says. ‘They wouldn’t worry about me.’

It’s an attitude I’ve heard from other black people and white people too, my parents included. That, back then, you didn’t disagree with the government; you just accepted that things were the way they were, you did your job and you kept quiet. Those who didn’t were marked out either as activists or sympathisers, both of which could land you in trouble.

Throughout our conversation, Jack insists that he was helping people – and that the people were grateful for what he was doing. The outsiders were coming and taking the locals’ jobs and women, he says. The locals wanted them out.

I ask him how the people reacted when he caught them.

‘They would fight,’ he says. ‘It was dangerous.’

That’s why he carried a gun.

‘Because it’s dangerous,’ he says again. ‘They can kill you.’

Sometimes, Jack says, he had to run. Other times he would get the police to go back with him. But he never had to use the gun, and no one ever as much as pointed a gun at him. Knives, yes, ‘to try to open the road and run,’ he says. ‘But if they see you’ve got a gun, nobody will bother you.’

He pauses for a long time. He’s not laughing now.

‘It was…’ he stops again.

‘Yoh, it was very hard. Because it’s my job. If I couldn’t do that, then I would be fired.’

He says people threatened to kill him sometimes, saying it wasn’t right, the job he was doing.

‘And I would say to them, “Give me a better job, and I will do that.”’