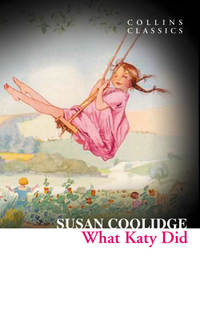

What Katy Did

Dorry and Joanna sat on the two ends of the ridge-pole. Dorry was six years old; a pale, pudgy boy, with rather a solemn face, and smears of molasses on the sleeve of his jacket. Joanna, whom the children called “John”, and “Johnnie”, was a square, splendid child, a year younger than Dorry; she had big brave eyes, and a wide rosy mouth, which always looked ready to laugh. These two were great friends, though Dorry seemed like a girl who had got into boy’s clothes by mistake, and Johnnie like a boy who, in a fit of fun, had borrowed his sister’s frock. And now, as they all sat there chattering and giggling, the window above opened, a glad shriek was heard, and Katy’s head appeared. In her hand she held a heap of stockings, which she waved triumphantly.

“Hurray!” she cried, “all done, and Aunt Izzie says we may go. Are you tired out waiting? I couldn’t help it, the holes were so big, and took so long. Hurry up, Clover, and get the things! Cecy and I will be down in a minute.”

The children jumped up gladly, and slid down the roof. Clover fetched a couple of baskets from the wood-shed. Elsie ran for her kitten. Dorry and John loaded themselves with two great faggots of green boughs. Just as they were ready, the side-door banged, and Katy and Cecy Hall came into the yard.

I must tell you about Cecy. She was a great friend of the children’s, and lived in a house next door. The yards of the houses were only separated by a green hedge, with no gate, so that Cecy spent two-thirds of her time at Dr. Carr’s, and was exactly like one of the family. She was a neat, dapper, pink-and-white-girl, modest and prim in manner, with light shiny hair which always kept smooth, and slim hands, which never looked dirty. How different from my poor Katy! Katy’s hair was for ever in a tangle; her gowns were always catching on nails and “tearing themselves”; and, in spite of her age and size, she was as heedless and innocent as a child of six. Katy was the longest girl that was ever seen. What she did to make herself grow so, nobody could tell; but there she was—up above papa’s ear, and half a head taller than poor Aunt Izzie. Whenever she stopped to think about her height she became very awkward, and felt as if she were all legs and elbows, and angles and joints. Happily, her head was so full of other things, of plans and schemes, and fancies of all sorts, that she didn’t often take time to remember how tall she was. She was a dear, loving child, for all her careless habits, and made bushels of good resolutions every week of her life, only unluckily she never kept any of them. She had fits of responsibility about the other children, and longed to set them a good example, but when the chance came, she generally forgot to do so. Katy’s days flew like the wind; for when she wasn’t studying lessons, or sewing and darning with Aunt Izzie, which she hated extremely, there were always so many delightful schemes rioting in her brains, that all she wished for was ten pairs of hands to carry them out. These same active brains got her into perpetual scrapes. She was fond of building castles in the air, and dreaming of the time when something she had done would make her famous, so that everybody would hear of her, and want to know her. I don’t think she had made up her mind what this wonderful thing was to be; but while thinking about it she often forgot to learn a lesson, or to lace her boots, and then she had a bad mark, or a scolding from Aunt Izzie. At such times she consoled herself with planning how, by-and-by, she would be beautiful and beloved, and amiable as an angel. A great deal was to happen to Katy before that time came. Her eyes, which were black, were to turn blue; her nose was to lengthen and straighten, and her mouth, quite too large at present to suit the part of a heroine, was to be made over into a sort of rosy button. Meantime, and until these charming changes should take place, Katy forgot her features as much as she could, though still, I think, the person on earth whom she most envied was that lady on the big posters with the wonderful hair which sweeps the ground.

CHAPTER 2

Paradise

The place to which the children were going was a sort of marshy thicket at the bottom of a field near the house. It wasn’t a big thicket, but it looked big, because the trees and bushes grew so closely that you could not see just where it ended. In winter the ground was damp and boggy, so that nobody went there, excepting cows, who don’t mind getting their feet wet; but in summer the water dried away, and then it was all fresh and green, and full of delightful things—wild roses, and sassafras, and birds’ nests. Narrow, winding paths ran here and there, made by the cattle as they wandered to and fro. This place the children called “Paradise”, and to them it seemed as wide and endless and full of adventure as any forest of fairyland.

The way to Paradise was through some wooden bars. Katy and Cecy climbed these with a hop, skip, and jump, while the smaller ones scrambled underneath. Once past the bars they were fairly in the field, and, with one consent, they all began to run till they reached the entrance of the wood. Then they halted, with a queer look of hesitation on their faces. It was always an exciting occasion to go to Paradise for the first time after the long winter. Who knew what the fairies might not have done since any of them had been there to see?

“Which path shall we go in by?” asked Clover, at last.

“Suppose we vote,” said Katy. “I say by the Pilgrim’s Path and the Hill of Difficulty.”

“So do I!” chimed in Clover, who always agreed with Katy.

“The Path of Peace is nice,” suggested Cecy.

“No, no! We want to go by Sassafras Path!” cried John and Dorry.

However, Katy, as usual, had her way. It was agreed that they should first try Pilgrim’s Path, and afterward make a thorough exploration of the whole of their little kingdom, and see all that had happened since last they were there. So in they marched, Katy and Cecy heading the procession, and Dorry, with his great trailing bunch of boughs, bringing up the rear.

“Oh, there is the dear rosary, all safe!” cried the children, as they reached the top of the Hill of Difficulty, and came upon a tall stump, out of the middle of which waved a wild rose-bush, budded over with fresh green leaves. This “rosary” was a fascinating thing to their minds. They were always inventing stories about it, and were in constant terror lest some hungry cow should take a fancy to the rosebush and eat it up.

“Yes,” said Katy, stroking a leaf with her finger, “It was in great danger one night last winter, but it escaped.”

“Oh! how? Tell us about it!” cried the others, for Katy’s stories were famous in the family.

“It was Christmas Eve,” continued Katy, in a mysterious tone. “The fairy of the rosary was quite sick. She had taken a dreadful cold in her head, and the poplar-tree fairy, just over there, told her that sassafras tea is good for colds. So she made a large acorn-cup full, and then cuddled herself in where the wood looks so black and soft, and fell asleep. In the middle of the night, when she was snoring soundly, there was a noise in the forest, and a dreadful black bull with fiery eyes galloped up. He saw our poor Rosy Posy, and, opening his big mouth, he was just going to bite her in two; but at that minute a little fat man, with a wand in his hand, popped out from behind the stump. It was Santa Claus, of course. He gave the bull such a rap with his wand that he moo-ed dreadfully, and then put up his fore-paw, to see if his nose was on or not. He found it was, but it hurt him so that he moo-ed again, and galloped off as fast as he could into the woods. Then Santa Claus waked up the fairy, and told her that if she didn’t take better care of Rosy Posy he should put some other fairy into her place, and set her to keep guard over a prickly, scratchy, blackberry bush.”

“Is there really any fairy?” asked Dorry, who had listened to this narrative with open mouth.

“Of course,” answered Katy. Then bending down toward Dorry, she added in a voice intended to be of wonderful sweetness: “I am a fairy, Dorry!”

“Pshaw!” was Dorry’s reply; “you’re a giraffe—Pa said so!”

The Path of Peace got its name because of its darkness and coolness. High bushes almost met over it, and trees kept it shady, even in the middle of the day. A sort of white flower grew there, which the children called Pollypods, because they didn’t know the real name. They stayed a long while picking bunches of these flowers, and then John and Dorry had to grub up an armful of sassafras roots; so that before they had fairly gone through Toadstool Avenue, Rabbit Hollow, and the rest, the sun was just over their heads, and it was noon.

“I’m getting hungry,” said Dorry.

“Oh, no, Dorry, you mustn’t be hungry till the bower is ready!” cried the little girls, alarmed, for Dorry was apt to be disconsolate if he was kept waiting for his meals. So they made haste to build the bower. It did not take long, being composed of boughs hung over skipping-ropes, which were tied to the very poplar tree where the fairy lived who had recommended sassafras tea to the fairy of the rose.

When it was done they all cuddled in underneath. It was a very small bower—just big enough to hold them, and the baskets, and the kitten. I don’t think there would have been room for anybody else, not even another kitten. Katy, who sat in the middle, untied and lifted the lid of the largest basket, while all the rest peeped eagerly to see what was inside.

First came a great many ginger cakes. These were carefully laid on the grass to keep till wanted: buttered biscuit came next—three apiece, with slices of cold lamb laid in between; and last of all were a dozen hard-boiled eggs, and a layer of thick bread and butter sandwiched with corned-beef. Aunt Izzie had put up lunches for Paradise before, you see, and knew pretty well what to expect in the way of appetite.

Oh, how good everything tasted in that bower, with the fresh wind rustling the poplar leaves, sunshine and sweet wood-smells about them, and birds singing overhead! No grown-up dinner-party ever had half so much fun. Each mouthful was a pleasure; and when the last crumb had vanished, Katy produced the second basket, and there—oh, delightful surprise!—were seven little pies—molasses pies, baked in saucers—each with a brown top and crisp candified edge, which tasted like toffy and lemon-peel, and all sorts of good things mixed up together.

There was a general shout. Even demure Cecy was pleased, and Dorry and John kicked their heels on the ground in a tumult of joy. Seven pairs of hands were held out at once toward the basket; seven sets of teeth went to work without a moment’s delay. In an incredibly short time every vestige of pie had disappeared, and a blissful stickiness pervaded the party.

“What shall we do now?” asked Clover, while little Phil tipped the baskets upside down, as if to make sure there was nothing left that could possibly be eaten.

“I don’t know,” replied Katy dreamily. She had left her seat, and was half-sitting, half-lying on the low crooked bough of a butternut-tree, which hung almost over the children’s heads.

“Let’s play we’re grown up,” said Cecy, “and tell what we mean to do?”

“Well,” said Clover, “you begin. What do you mean to do?”

“I mean to have a black silk dress, and pink roses in my bonnet, and a white muslin long-shawl,” said Cecy; “and I mean to look exactly like Minerva Clark! I shall be very good, too; as good as Mrs. Bedell, only a great deal prettier. All the young gentlemen will want me to go and ride, but I shan’t notice them at all, because you know I shall always be teaching in Sunday-school, and visiting the poor. And some day, when I am bending over an old woman, and feeding her with currant jelly, a poet will come along and see me, and he’ll go home and write a poem about me,” concluded Cecy triumphantly.

“Pooh!” said Clover. “I don’t think that would be nice at all. I’m going to be a beautiful lady—the most beautiful lady in the world! And I’m going to live in a yellow castle, with yellow pillars to the portico, and a square thing on top, like Mr. Sawyer’s. My children are going to have a playhouse up there. There’s going to be a spy-glass in the window, to look out of. I shall wear gold dresses and silver dresses every day, and diamond rings, and have white satin aprons to tie on when I’m dusting, or doing anything dirty. In the middle of my backyard there will be a pond-full of scent, and whenever I want any I shall go just out and dip a bottle in. And I shan’t teach in Sunday-schools, like Cecy, because I don’t want to; but every Sunday I’ll go and stand by the gate, and when her scholars go by on their way home I’ll put some scent on their handkerchiefs.”

“I mean to have just the same,” cried Elsie, whose imagination was fired by this gorgeous vision, “only my pond will be the biggest. I shall be a great deal beautifuller, too,” she added.

“You can’t,” said Katy from overhead. “Clover is going to be the most beautiful lady in the world.”

“But I’ll be more beautiful than the most beautiful,” persisted poor little Elsie; “and I’ll be big, too, and know everybody’s secrets. And everybody’ll be kind then, and never run away and hide; and there won’t be any post-offices, or anything disagreeable.”

“What’ll you be, Johnnie?” asked Clover, anxious to change the subject, for Elsie’s voice was growing plaintive.

But Johnnie had no clear ideas as to her future. She laughed a great deal, and squeezed Dorry’s arm very tight, but that was all. Dorry was more explicit.

“I mean to have turkey every day,” he declared, “and batter-puddings; not boiled ones, you know, but little baked ones, with brown shiny tops, and a great deal of pudding-sauce to eat on them. And I shall be so big then that nobody will say, ‘Three helps is quite enough for a little boy.’”

“Oh, Dorry, you pig!” cried Katy, while the others screamed with laughter. Dorry was much affronted.

“I shall just go and tell Aunt Izzie what you called me,” he said, getting up in a great pet.

But Clover, who was a born peacemaker, caught hold of his arm, and her coaxing and entreaties consoled him so much that he finally said he would stay; especially as the others were quite grave now, and promised that they wouldn’t laugh any more.

“And now, Katy, it’s your turn,” said Cecy; “tell us what you’re going to be when you grow up.”

“I’m not sure about what I’ll be,” replied Katy, from overhead; “beautiful, of course, and good if I can, only not so good as you, Cecy, because it would be nice to go and ride with the young gentlemen, sometimes. And I’d like to have a large house and a splendiferous garden, and then you could all come and live with me, and we would play in the garden, and Dorry should have turkey five times a day if he liked. And we’d have a machine to darn the stockings, and another machine to put the bureau drawers in order, and we’d never sew or knit garters, or do anything we didn’t want to. That’s what I’d like to be. But now I’ll tell you what I mean to do.”

“Isn’t it the same thing?” asked Cecy.

“Oh, no!” replied Katy, “quite different; for you see I mean to do something grand. I don’t know what yet; but when I’m grown up I shall find out.” (Poor Katy always said “when I’m grown up”, forgetting how very much she had grown already.) “Perhaps,” she went on, “it will be rowing out in boats, and saving people’s lives, like that girl in the book. Or perhaps I shall go and nurse in the hospital, like Miss Nightingale. Or else I’ll head a crusade and ride on a white horse, with armour and a helmet on my head, and carry a sacred flag. Or if I don’t do that, I’ll paint pictures, or sing, or scalp—sculp—what is it? you know—make figures in marble. Anyhow it shall be something. And when Aunt Izzie sees it, and reads about me in the newspapers, she will say, ‘The dear child! I always knew she would turn out an ornament to the family.’ People very often say afterward that they ‘always knew’,” concluded Katy sagaciously.

“Oh, Katy! how beautiful it will be!” said Clover, clasping her hands. Clover believed in Katy as she did in the Bible.

“I don’t believe the newspapers would be so silly as to print things about you, Katy Carr,” put in Elsie, vindictively.

“Yes, they will!” said Clover, and gave Elsie a push.

By-and-by John and Dorry trotted away on mysterious errands of their own.

“Wasn’t Dorry funny with his turkey?” remarked Cecy; and they all laughed again.

“If you won’t tell,” said Katy, “I’ll let you see Dorry’s journal. He kept it once for almost two weeks, and then gave it up. I found the book this morning in the nursery closet.”

All of them promised, and Katy produced it from her pocket. It began thus:— “March 12.—Have resolved to keep a jurnal.

“March 13.—Had rost befe for dinner, and cabage, and potato and appel sawse, and rice-puding. I do not like rice-puding when it is like ours. Charley Slack’s kind is rele good. Mush and sirup for tea.

“March 19.—Forgit what did. John and me saved our pie to take to schule.

“March 21.—Forgit what did. Gridel cakes for brekfast. Debby didn’t fry enuff.

“March 24.—This is Sunday. Corn-befe for dinnir. Studdied my Bibel leson. Aunt Issy said I was gredy. Have resolved not to think so much about things to ete. Wish I was a beter boy. Nothing pertikeler for tea.

“March 25.—Forgit what did.

“March 27.—Forgit what did.

“March 29.—Played.

“March 31.—Forgit what did.

“April 1.—Have dissided not to kepe a jurnal enny more.”

Here ended the extracts; and it seemed as if only a minute had passed since they stopped laughing over them, before the long shadows began to fall, and Mary came to say that all of them must come in to get ready for tea. It was dreadful to have to pick up the empty baskets and go home, feeling that the long, delightful Saturday was over, and that there wouldn’t be another for a week. But it was comforting to remember that Paradise was always there; and that at any moment when Fate and Aunt Izzie were willing they had only to climb a pair of bars—very easy ones, and without any fear of an angel with flaming sword to stop the way—enter in, and take possession of their Eden.

CHAPTER 3

The Day of Scrapes

Mrs. Knight’s school, to which Katy and Clover and Cecy went, stood quite at the other end of the town from Dr. Carr’s. It was a low, one-story building and had a yard behind it, in which the girls played at recess. Unfortunately, next door to it was Miss Miller’s school, equally large and popular, and with a yard behind it also. Only a high board fence separated the two playgrounds.

Mrs. Knight was a stout, gentle woman, who moved slowly, and had a face which made you think of an amiable and well-disposed cow. Miss Miller, on the contrary, had black eyes, with black corkscrew curls waving about them, and was generally brisk and snappy. A constant feud raged between the two schools as to the respective merits of the teachers and the instruction. The Knight girls, for some unknown reason, considered themselves genteel and the Miller girls vulgar, and took no pains to conceal this opinion; while the Miller girls, on the other hand, retaliated by being as aggravating as they knew how. They spent their recesses and intermissions mostly in making faces through the knot-holes in the fence, and over the top of it, when they could get there, which wasn’t an easy thing to do, as the fence was pretty high. The Knight girls could make faces too, for all their gentility. Their yard had one great advantage over the other: it possessed a wood-shed, with a climbable roof, which commanded Miss Miller’s premises, and upon this the girls used to sit in rows, turning up their noses at the next yard, and irritating the foe by jeering remarks. “Knights” and “Millerites” the two schools called each other; and the feud raged so high that sometimes it was hardly safe for a Knight to meet a Millerite in the street; all of which, as may be imagined, was exceedingly improving both to the manners and morals of the young ladies concerned.

One morning, not long after the day in Paradise, Katy was late. She could not find her things. Her algebra, as she expressed it, had “gone and lost itself”, her slate was missing, and the string was off her sun-bonnet. She ran about, searching for these articles and banging doors, till Aunt Izzie was out of patience.

“As for your algebra,” she said, “if it is that very dirty book with only one cover, and scribbled all over the leaves, you will find it under the kitchen-table. Philly was playing before breakfast that it was a pig: no wonder, I’m sure, for it looks good for nothing else. How you do manage to spoil your school-books in this manner, Katy, I cannot imagine. It is less than a month since your father got you a new algebra, and look at it now—not fit to be carried about. I do wish you would realise what books cost!

“About your slate,” she went on, “I know nothing; but here is the bonnet-string;” taking it out of her pocket.

“Oh, thank you!” said Katy, hastily sticking it on with a pin.

“Katy Carr!” almost screamed Miss Izzie, “what are you about? Pinning on your bonnet-string. Mercy on me! what shiftless thing will you do next? Now stand still and don’t fidget! You shan’t stir till I have sewed it on properly.”

It wasn’t easy to “stand still and not fidget”, with Aunt Izzie fussing away and lecturing, and now and then, in a moment of forgetfulness, sticking her needle into one’s chin. Katy bore it as well as she could, only shifting perpetually from one foot to the other, and now and then uttering a little snort, like an impatient horse. The minute she was released she flew into the kitchen, seized the algebra, and rushed like a whirlwind to the gate, where good little Clover stood patiently waiting, though all ready herself, and terribly afraid she should be late.

“We shall have to run,” gasped Katy, quite out of breath. “Aunt Izzie kept me. She has been so horrid!”

They did run as fast as they could, but time ran faster, and before they were half-way to school the town clock struck nine, and all hope was over. This vexed Katy very much; for, though often late, she was always eager to be early.

“There,” she said, stopping short, “I shall just tell Aunt Izzie that it was her fault. It is too bad.” And she marched into school in a very cross mood.

A day begun in this manner is pretty sure to end badly, as most of us know. All the morning through things seemed to go wrong. Katy missed twice in her grammar lesson, and lost her place in the class. Her hand shook so when she copied her composition that the writing, not good at best, turned out almost illegible, so that Mrs. Knight said it must all be done over again. This made Katy crosser than ever; and, almost before she thought, she had whispered to Clover, “How hateful!” And then, when just before recess all who had been speaking were requested to stand up, her conscience gave such a twinge that she was forced to get up with the rest, and see a black mark put against her name on the list. The tears came into her eyes from vexation; and, for fear the other girls would notice them, she made a bolt for the yard as soon as the bell rang, and mounted up all alone to the wood-house roof, where she sat with her back to the school, fighting with her eyes, and trying to get her face in order before the rest should come.

Miss Miller’s clock was about four minutes slower than Mrs. Knight’s, so the next playground was empty. It was a warm, breezy day, and as Katy sat there, suddenly a gust of wind came, and seizing her sun-bonnet, which was only half tied on, whirled it across the roof. She clutched after it as it flew, but too late. Once, twice, thrice it flapped, then it disappeared over the edge, and Katy, flying after, saw it lying a crumpled lilac heap in the very middle of the enemy’s yard.