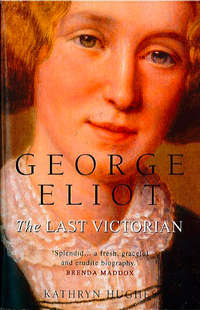

George Eliot: The Last Victorian

GEORGE

ELIOT

The LAST VICTORIAN

KATHRYN HUGHES

Dedication

For my parentsAnne and John Hughesagain

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

CHAPTER 1: ‘Dear Old Griff’ Early Years 1819–28

CHAPTER 2: ‘On Being Called a Saint’ An Evangelical Girlhood 1828–40

CHAPTER 3: ‘The Holy War’ Coventry 1840–1

CHAPTER 4: ‘I Fall Not In Love With Everyone’ The Rosehill Years 1841–9

CHAPTER 5: ‘The Land of Duty and Affection’ Coventry, Geneva and London 1849–51

CHAPTER 6: ‘The Most Important Means of Enlightenment’ Life at The Westminster Review 1851–2

CHAPTER 7: ‘A Man of Heart and Conscience’ Meeting Mr Lewes 1852–4

CHAPTER 8: ‘I Don’t Think She Is Mad’ Exile 1854–6

CHAPTER 9: ‘The Breath of Cows and the Scent of Hay’ Scenes of Clerical Life and Adam Bede 1856–9

CHAPTER 10: ‘A Companion Picture of Provincial Life’ The Mill on the Floss 1859–60

CHAPTER 11: ‘Pure, Natural Human Relations’ Silas Marner and Romola 1860–3

CHAPTER 12: ‘The Bent of My Mind Is Conservative’ Felix Holt and The Spanish Gypsy 1864–8

CHAPTER 13: ‘Wise, Witty and Tender Sayings’ Middlemarch 1869–72

CHAPTER 14: ‘Full of the World’ Daniel Deronda 1873–6

CHAPTER 15: ‘A Deep Sense of Change Within’ Death, Love, Death 1876–80

Epilogue

Select Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Notes

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1

‘Dear Old Griff’

Early Years 1819–28

IN THE EARLY hours of 22 November 1819 a baby girl was born in a small stone farmhouse, tucked away in the woodiest part of Warwickshire, about four miles from Nuneaton. It was not an important event. Mary Anne was the fifth child and third daughter of Robert Evans, and the terse note Evans made in his diary of her arrival suggests that he had other things to think about that day.1 As land agent to the Newdigate family of Arbury Hall, the forty-six-year-old Evans was in charge of 7000 acres of mixed arable and dairy farmland, a coal-mine, a canal and, his particular love, miles of ancient deciduous forest, the remnants of Shakespeare’s Arden. A new baby, a female too, was not something for which a man like Robert Evans had time to stop.

Six months earlier another little girl, equally obscure in her own way, had been born in a corner of Kensington Palace. Princess Alexandrina Victoria was also the child of a middle-aged man, the fifty-two-year-old Prince Edward of Kent, himself the fourth son of Mad King George III. None of George’s surviving twelve children had so far managed to produce a viable heir to succeed the Prince Regent, who was about to take over as king in his own right. It had been made brutally clear to the four elderly remaining bachelors, Edward among them, that the patriotic moment had come to give up their mistresses, acquire legal wives and produce a crop of lusty boys. But despite three sketchy, resentful marriages, the desired heir had yet to appear. Still, at this point it was too soon to give up hope completely. Princess Alexandrina Victoria, born on 24 May 1819, was promisingly robust and her mother, while past thirty, was young enough to try again for a son. If anyone bothered to think ahead for the little girl, the most they might imagine was that she would one day become the elder sister of a great king.

Officially the futures of these two little girls, Mary Anne and Alexandrina Victoria, were not promising. As for every other female child born that year, the worlds of commerce, industry and the professions were closed to them. As adults they would not be able to speak in the House of Commons, or vote for someone to do so on their behalf. They would not be eligible to take a degree at one of the ancient universities, become a lawyer, or manage the economic processes which were turning Britain into the most powerful nation on earth. Instead, their duties would be assumed to lie exclusively at home, whether palace or farmhouse, as companions and carers of husbands, children and ageing parents.

Yet that, as we know, is not what happened. Neither girl lived the life that the circumstances of her birth had seemed to decree. Instead, each emerged from obscurity to define the tone and temper of the age. Princess Alexandrina Victoria, pushed further up the line of succession by her father’s early death, even gave her name to it. ‘Victorian’ became the brand name for a confident, expansive hegemony which was extended absent-mindedly beyond her own lifetime. ‘Victorian’ was the sound of unassailable depth, stretch and solidity. It meant money in the bank and ships steaming the earth, factories that clattered all night and buildings that stretched for the sky. Its shape was the odd little figure of Victoria herself, sweet and girlish in the early years, fat and biddyish at the end. Wherever ‘Victorian’ energy and bustle made themselves felt, you could be sure to find that distinctive image, stamped into coins and erected in stone, woven into tablecloths and framed in cheap wood. In its ordinary femininity the figure of Victoria offered the moral counterpoise to all that striving and getting. The solid husband, puffy bosom and string of children represented the kind of good woman for whom Britain was busy getting rich.

George Eliot’s image, by contrast, was rarely seen by anyone. Indeed, it was whispered that she was so hideous that, Medusalike, you only had to look upon her to be turned to stone. And her name, during its early years of fame, suggested the very opposite of Victorianism. Her avowed agnosticism, sexual freedom, commercial success and childlessness were troubling reminders of everything that had been repressed from the public version of life under the great little Queen. By 1860 Victoria and Eliot had come to stand for the twin poles of female behaviour, respectability and disgrace. One gave her name to virtuous repression, a rigid channelling of desire into the safe haven of marriage and family. The other, made wickeder by male disguise, became a symbol of the ‘Fallen Woman’, banished to the edges of society or, in Eliot’s actual case, to a series of dreary suburban exiles.

That was the bluster. In real life – that messy matter which refuses to run along official lines – the Queen and Eliot shared more than distracted, greying fathers. Their emotional inheritance was uncannily similar and pressed their lives into matching moulds. Both had mothers who were intrusive yet remote, a tension which left them edgy for affection until the end of their days. Victoria slept in the Duchess of Kent’s room right up to her coronation, while Eliot spent her first thirty years looking for comfortable middle-aged women whom she could call ‘Mother’. When it came to men, both clung with the hunger of children rather than the secure attachment of grown women. Prince Albert and George Henry Lewes not only negotiated the public world for their partners, but lavished them with the intense and symbiotic affection usually associated with maternally minded wives. And when both men died before them, their widows fell into an extended stupor which recalled the despair of an abandoned baby.

What roused them in the end were intense connections with new and unsuitable men. The Queen found John Brown, then the Munshi, both servants, one black. Eliot, meanwhile, married John Cross, a banker twenty years younger and with nothing more than a gentleman’s education. Menopausal randiness was sniggeringly invoked as the reason for these ludicrous liaisons. Victoria was called ‘Mrs Brown’ behind her back. And when John Cross had to be fished out of Venice’s Grand Canal during his honeymoon, the whisper went round the London clubs that he had preferred to drown rather than make love to the hideous old George Eliot.

Because of Eliot’s ‘scandalous’ private life, which actually the Queen did not think so very bad, there was no possibility of the two women meeting. Yet recognising their twinship, they stalked each other obliquely down the years. Eliot first mentions Victoria in 1848 when, having briefly caught the revolutionary mood, she speaks slangily in a letter of ‘our little humbug of a queen’.2 Ironically, only eleven years later, Victoria had fallen in love with Eliot’s first full-length novel, Adam Bede, because of what she saw as its social conservatism, its warm endorsement of the status quo. The villagers of Hayslope, headed by Adam himself, reminded her of her beloved Highland servants, and in 1861 she commissioned paintings of two of the book’s central scenes by the artist Edward Henry Corbould.

George Eliot noticed how hard the Queen took the loss of Prince Albert in 1861 and, aware of the similarities in their age and temperament, wondered how she would manage the dreadful moment when it came to her. The Queen, in turn, was touched by the delicate letter of condolence that Eliot and Lewes wrote to one of her courtier’s children on his death and asked whether she might tear off their double signature as a memento.3

The Queen’s daughters went even further. By the 1870s Eliot’s increasing celebrity and the evident stability of her relationship with Lewes meant that she was no longer a total social exile. Among the great and the good who pressed for an introduction were two of the royal princesses. Brisk and bright, Vicky and Louise lobbied behind the scenes for a meeting and then, in Louise’s case at least, dispensed with royal protocol by coming up to speak to George Eliot first.4

The princesses were among the thousands of ordinary Victorians, neither especially clever nor brave, who ignored the early grim warnings of clergymen and critics about the ‘immorality’ of George Eliot’s life and work. By the 1860s working-class men and middle-class mothers, New Englanders (that most puritan of constituencies) and Jews, Italians and Australians were all reading her. Cheap editions and foreign translations carried George Eliot into every kind of home. Even lending libraries, those most skittishly respectable of ‘family’ institutions, bowed to consumer demand and grudgingly increased their stock of Adam Bede and The Mill on the Floss.

What is more, all these Victorians read the damnable George Eliot with an intensity and engagement that was never the case with Dickens or Trollope. While readers of Bleak House might sniff over the death of Jo and even stir themselves to wonder whether something might not be done for crossing-sweepers in general, they did not bombard Dickens with letters asking how they should live. That intimate engagement was reserved for Eliot, who alone seemed to understand the pain and difficulty of being alive in the nineteenth century. From around the world, men and women wrote to her begging for advice about the most personal matters, from marriage through God to their own poetry. Or else, like Princess Louise, they stalked her at concert halls, hoping for a word or a glance.

The worries which Eliot’s troubled readers laid before her concerned the dislocations of a social and moral world that was changing at the speed of light. Here were the doubts and disorientations that had been displaced from that triumphant version of Victorianism. An exploding urban population, for instance, might well suggest bustling productivity, but it could also mean a growing sense of social anomie. Rural communities were indeed invigorated by their new proximity to big towns, but they were also losing their fittest sons and daughters to factories and, later, to offices and shops. Meanwhile the suburbs, conceived as a rus in urbe, pleased no one, least of all George Eliot, who spent five years hating Richmond and Wandsworth for their odd mix of nosy neighbours and lack of real green.

For if in one way Victorians felt more separate from each other, in others they were being offered opportunities to come together as never before. It was not just the railway that was changing the psycho-geography of the country, bringing friends, enemies and business partners into constant contact. The postal service, democratised in 1840 by the introduction of the Penny Post, allowed letters to fly from one end of the country to the other at a pace that makes our own mail service look like a slowcoach. Then there was the telephone which, at the end of her life, George Eliot was invited to try. As a result of these changes Victorians found themselves pulled in two directions. Scattering from their original communities, they spent the rest of their lives trying to reconstitute these earlier networks in imaginary forms.

Science, too, was taking away the old certainties and replacing them with new and sometimes painful ones. It would not be until 1859 that Darwin would publish Origin of Species, but plenty of other geologists and biologists were already embracing the possibility that the world was older than Genesis suggested, in which case the Bible was perhaps not the last word on God’s word. Perhaps, indeed, it was not God’s word at all, but rather the product of man’s need to believe in something other than himself. This certainly was the double conclusion that Eliot came to during the early anonymous years of her career when she translated those seminal German texts, Strauss’s The Life of Jesus (1835–6) and Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity (1841). Her readers likewise wrestled with the awful possibility that there was no moral authority except the one which was to be found by digging deep within themselves. Not only did a godless universe lay terrifying burdens of responsibility upon the individual, but it unsettled the idea of an afterlife. To a culture which had always believed that, no matter how dismal earthly life might be, there was a reward waiting in heaven, this was a horrifying blow beside which the possibility that one was an ape paled into insignificance.

That much-vaunted prosperity turned out to be a tricky business too. For every Victorian who felt rich, there were two who felt very poor indeed, especially during the volatile 1840s and again in the late 1860s. During Eliot’s early years in the Midlands she saw the effect of trade slumps on the lives of working families. As a schoolgirl in Nuneaton she had watched while idle weavers queued for free soup; at home, during the holidays, she sorted out second-hand clothing for unemployed miners’ families. Even her own sister, married promisingly to a gentlemanly doctor, found herself as a widow fighting to stay out of the workhouse.

To middle-class Victorians these sights and stories added to a growing sense that they were not, after all, in control of the economic and social revolution being carried out in their name. Getting the vote in 1832 had initially seemed to give them the power to reshape the world in their own image: the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 had represented a real triumph of urban needs over the agricultural interest. But it soon became clear that early fears that 1832 would be the first step towards a raggle-taggle democracy were justified. On three occasions during the ‘hungry forties’ working-class men and women rallied themselves around the Charter, a frightening document demanding universal suffrage and annual parliaments. By the mid-186os, with the economy newly unsettled, urban working men were once again agitating violently for the vote.

These were worrying times. The fat little figure of the Queen was not enough to soothe Victorians’ fears that the blustery world in which they lived might not one day blow apart completely. In fear and hope they turned to the woman whose name they were initially only supposed to whisper and whose image they were seldom allowed to see. George Eliot’s novels offered Victorians the chance to understand their edginess in its wider intellectual setting and to rehearse responses by identifying with characters who looked and sounded like themselves. Thanks to her immense erudition in everything from theology to biology, anthropology to psychology, Eliot was able to give current doubts their proper historic context. Dorothea’s ardent desire to do great deeds, for instance, is set alongside St Teresa’s matching passion in the sixteenth century and their contrasting destinies explained. In the same way Tom Tulliver’s battles with his sister Maggie are understood not just in terms of their individual personalities, but as the meeting point of several arcs of genetic, cultural, and family conditioning at a particular moment in human history.

While disenchantment with Victorianism led readers to George Eliot, George Eliot’s advice to them was that they should remain Victorians. Despite the ruptures of the speedy present, Eliot believed that it was possible, indeed essential, that her readers stay within the parameters of the ‘working-day world’ – a phrase that would stand at the heart of her philosophy. She would not champion an oppositional culture, in which people put themselves outside the ordinary social and human networks which both nurtured and frustrated them. From Darwin she took not just the radical implications (we are all monkeys, there is probably no God), but the conservative ones too. Societies evolve over thousands of years; change – if it is to work – must come gradually and from within. Opting out into political, religious or feminist Utopias will not do. Eliot’s novels show people how they can deal with the pain of being a Victorian by remaining one. Hence all those low-key endings which have embarrassed feminists and radicals for over a century. Dorothea’s ardent nature is pressed into small and localised service as an MP’s wife, Romola’s phenomenal erudition is set aside for her duties as a sick-nurse, Dinah gives up her lay preaching to become a mother.

Eliot’s insistence on making her characters stay inside the community, acknowledge the status quo, give up fantasies about the ballot, behave as if there is a God (even if there isn’t) bewildered her peers. Feminist and radical friends assumed that a woman who lived with a married man, who had broken with her family over religion, who was one of the highest-earning women in Britain, must surely be encouraging others to do the same. And when they found that she did not want the vote for women, that she felt remote from Girton and that she sometimes even went to church, they felt baffled and betrayed.

What Eliot’s critics missed was that she was no reactionary, desperately trying to hold back the moment when High Victorianism would crumble. Right from her earliest fictions, from the days of Adam Bede in 1859, she had understood her culture’s fragility, as well as its enduring strengths. None the less, she believed in the Victorian project, that it was possible for mankind to move forward towards a place or time that was in some way better. This would only happen by a slow process of development during which men and women embraced their doubts, accepted that there would be loss as well as gain, and took their enlarged vision and diminished expectations back into the everyday struggle. In Daniel Deronda, Eliot’s penultimate book and last proper novel, she shows how this new Victorianism, projected on to a Palestinian Jewish homeland, might look and sound. Although it will cohere around a particular social, geographic and religious culture, it will acknowledge other centres and identities. It will know and honour its own past, while anticipating a future which is radically different. By being sure of its own voice, it will be able to listen attentively to those of others.

It was Eliot’s adult reading of Wordsworth and Scott that instilled in her the conviction that ‘A human life, I think, should be well rooted in some spot of a native land … a spot where the definiteness of early memories may be inwrought with affection.’5 But it was during her earliest years, as she accompanied her father around the Arbury estate in his pony trap, that she fell deeply in love with the Midlands countryside. Her ‘spot’ was Warwickshire, the midmost county of England. Uniquely, the landscape was neither agricultural nor industrial, but a patchwork of both. In a stunning Introduction to Felix Holt, The Radical, George Eliot used the device of a stagecoach thundering across the Midlands on the eve of the 1832 Reform Act to describe a countryside where the old and new sit companionably side by side.

In these midland districts the traveller passed rapidly from one phase of English life to another: after looking down on a village dingy with coal-dust, noisy with the shaking of looms, he might skirt a parish all of fields, high hedges, and deep-rutted lanes; after the coach had rattled over the pavement of a manufacturing town, the scene of riots and trades-union meetings, it would take him in another ten minutes into a rural region, where the neighbourhood of the town was only felt in the advantages of a near market for corn, cheese, and hay.6

Mary Anne’s early life, contained within the four walls of Griff farmhouse, where her family moved early in 1820, still belonged securely to the agricultural ‘phase of English life’ and was pegged to the daily and seasonal demands of a mixed dairy and arable farm. Although there were male labourers to do the heavy work and female servants to help in the house, much of the responsibility was shouldered by the Evans family itself. Like many of the farmers’ wives who appear in Eliot’s books, Mrs Evans took particular pride in her dairy, running it as carefully as Mrs Poyser in Adam Bede, who continually frets about low milk yields and late churnings. Like the wealthy but practical Nancy Lammeter in Silas Marner, too, Mrs Evans and her two daughters had bulky, well-developed hands which ‘bore the traces of butter-making, cheese-crushing, and even still coarser work’.7 Some years after George Eliot’s death, a rumour circulated in literary London that one of her hands was bigger than the other, thanks to years of turning the churn. It was a story which her brother Isaac, now gentrified by a fancy education, good marriage and several decades of high agricultural prices, hated to hear repeated.

The rhythms of agricultural life made themselves felt right through Mary Anne’s young adulthood. As a prickly, bookish seventeen-year-old left to run the farmhouse after her mother’s death, she railed against the fuss and bother of harvest supper and the hiring of new servants each Michaelmas. And yet the very depth of her adolescent alienation from this repetitive, witless way of life reveals how deeply it remained embedded in her. Thirty years on and established in a villa in London’s Regent’s Park, her first thought about the weather was always how it would affect the crops.

But life on the Arbury estate was no bucolic idyll. The Newdigate lands contained some of the richest coal deposits in the county. As she grew older, the fields in which Mary Anne played had names like Engine Close and Coal-pit Field. Lumps of coal lay casually amid the grass. At night the girl was kept awake by the chug-chug of the Newcomen engine pumping water out of the mine less than a mile from her home. The canal in which she and Isaac fished was busy with barges taking the coal to Coventry. And when Mary Anne accompanied her father on his regular visits to Mr Newdigate at Arbury Hall, she would have noticed the huge crack which cut across the gold-and-white ceiling of the magnificent great hall. Subsidence caused by the mine-working had dramatically marked a building whose elaborate refashioning only a generation before had come to stand for everything that was elegantly Arcadian about aristocratic life.