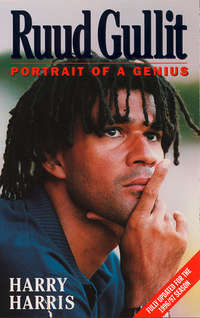

Ruud Gullit: Portrait of a Genius

Copyright

Harper Non-Fiction

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in hardback 1996 by CollinsWillow

First published in paperback in 1997

Copyright © Harry Harris 1997

Harry Harris asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780002187817

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2016 ISBN: 9780008192068

Version: 2016-06-03

Dedication

To Linda ⦠a true Chelsea fan

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 âIâm Not A Foreigner â Iâm a World Travellerâ

2 Rebuilding the Bridge

3 Gullit Mania

4 A New Season, a New Challenge

5 Dreaming of Total Football

6 Cup Battles

7 The Troubleshooter

8 Ruud Awakening

9 Italy â the Dream that Turned Sour

10 World Stage

11 Private Life: The Man Behind the Dreadlocks

12 Boss of the Bridge

13 A Cup-Winning Season

Career Highlights

Index

About the Author

About the Publisher

Acknowledgements

My thanks to close Dutch friend and colleague Marcel van der Kraan for his expert views on the young Ruud Gullit; Godric Smith at the Conservative Party Press Office; and to former Prime Minister John Major for offering his views on Ruud. Plus all the other MPs, celebrities and people in the game who contributed their opinions. My thanks also go to Chelsea chairman Ken Bates, chief executive Colin Hutchinson, Ruudâs UK advisors Jon and Phil Smith of First Artists Corporation, and Sky TV press officer Chris Haynes. The Daily Mirror provided a number of pictures for the book, and it was nice to get so much co-operation from my âFleet Streetâ colleagues, notably Michael Hart and photographer Frank Tewkesbury for the snap of Ruud winning the Evening Standard Footballer of the Month award for January 1996, for which Ruud insisted all his team-mates appear! At publishers HarperCollins, praise too for Editorial Director Michael Doggart for recognising straight away my conviction that a biography of Ruud Gullit would make such fascinating reading; Tom Whiting for his patience and helpful suggestions; and Andrew Clark and David Williams for their diligent sub-editing.

Finally, a special thanks to Dutch photographer Peter Smoulders for his excellent portfolio of Ruud Gullit pictures.

Introduction

The first non-British manager to reach the FA Cup Final is none other than the charismatic Dutchman Ruud Gullit. This is all the more remarkable considering that he achieved this distinction in his very first season in football management.

When he was informed that he had made English football history after Chelseaâs FA Cup semi-final demolition of Wimbledon at Highbury in April 1997, it was a moment to savour, a special achievement even in his distinguished career. âI have just been told that I am the first foreign coach to take a team to Wembley in an FA Cup final and am very proud of that. But it is important we win it, as first place is the only thing that matters in any competition.â And win it they did, in true style.

Gullitâs first season in charge produced a whirlwind of activity at the Bridge. Witnessed by thousands of fans were a kaleidoscope of spectacular goals, famous victories and disappointing defeats. Winning at Old Trafford and beating mighty Liverpool twice at the Bridge would be etched forever in the memories of Chelsea supporters â including that epic 4â2 win in the fourth round FA Cup tie after being two goals down, a match seen by millions on BBC TV.

English football has been a graveyard for foreign managers. Their track record is a litany of disaster. In recent years Dr Joe Venglos at Aston Villa and Ossie Ardiles at Newcastle and then Tottenham have flopped. Gullit broke the mould, as has Arsene Wenger at Arsenal.

But Chelseaâs managing director, Colin Hutchinson, explained that Gullitâs management role is not typical. âEnglish football is entering the era of the coach. It is the Continental way and Chelsea are pioneering this with Ruud working in a classic Continental set-up. He identifies the players he wants and I try to get them. We were fortunate that Ruud had a year in the Premier League as a player to get to know the English game and fellow Blues before taking over as player-manager. It would have been too much to have asked him to play, coach and manage when he first arrived in London from Sampdoria.

âHad Ruud turned down the player-manager role, Chelsea might still have gone Continental. Arsene Wenger was a possibility, although indications were that he would not be available until well into the season. Sven Ericksson, who has had European success with Malmo, Benfica and Sampdoria, was another prospect.

âPremiership squads will continue to be multi-national. The next big invasion could be from Continental coaches, which would be another step on the road to helping raise standards and the technical quality of the English game. If that makes our clubs a stronger force in European competitions, then it will be for the good. Until Englandâs clubs start winning European cups we wonât be seriously considered as the number one league in the world.â

Gullit has helped to transform English football by incorporating a host of ideas from Italy, where he was the worldâs number one with AC Milan. Look at his pre-Chelsea career and you can easily deduce why many of his players say they have learned so much from him. Gullitâs honours include World Footballer of the Year (1987); European Footballer of the Year (1987); European Championships winner (1988); European Cup winner (1989, 1990); Italian League title winner (1988, 1992, 1993) and Dutch League title winner (1984, 1986 1987); 66 caps for Holland and scorer of 16 international goals. Gullit also wins the praise of footballâs top players. George Weah, World Footballer of the Year in 1996, recalls meeting him when they both played for the Rest of the World XI in Munich. âHe was very pleasant and respectful. He spoke to me like a son or a brother. He was full of encouragement and came across as a superb role model for us all. I really admire him as a player. Like Eric Cantona, Ruud always speaks the truth. He never hides from it and that has earned him huge respect worldwide.â In his first season as a player in England, Gullit was quick to win the respect of the UK fans. He was named 1996âs Best International Player in the UK by readers of the football magazines World Soccer, Goal, 90 Minutes, Soccer Stars and Shoot.

His innovations have been a breath of fresh air for the traditional English game, and he has implemented them without any grey flecks appearing on his famous dreadlocks. This isnât to say that Mr Super Cool doesnât experience any emotion. âI think the very best time is the relief of scoring a goal or watching the celebrations of the players after scoring.â

While Kevin Keegan and other high-profile bosses were struck down by burn-out, it was a stress-free zone for Gullit, who in the summer of 1996 managed from the bench in an Armani suit and no socks, and in the winter of 1996/97 with fashionable apparel, including a bobble hat to keep not only his head warm but also his dreadlocks dry.

Voted Britainâs Best Dressed Man, Ruud was signed up for his own designer label Ruud Wear. The BBC negotiated a two-year contract after his roaring success with Des Lynam and Alan Hansen during Euro 96, and he signed a lucrative TV commercial deal to advertise M&Ms.

In his first six months in charge he bought and sold 12 players for a transfer turnover of more than £18 million. He imported Gianluca Vialli, Gianfranco Zola, and Roberto di Matteo and Frank Leboeuf for a cost of £12 million and sold old favourites such as John Spencer, Terry Phelan and Gavin Peacock. Ruud also sold Paul Furlong and youngsters such as Anthony Barness and Muzzy Izzett, with Mark Stein and David Rocastle loaned out.

The players Gullit recruited sent the wage bill soaring to £15 million a year. Accounting for the lionâs share were the £25, 000-a-week salaries of the Italian superstars, who are among Chelseaâs nouveaux-riches and regularly dine at San Lorenzoâs, Princess Dianaâs favourite Kensington eatery.

By Gullitâs own admission the 1996/97 football season was a âroller coaster yearâ. But how the fans loved it. The average home game attendance was 27, 600 â the best for nine years. Season ticket sales for 1997/98 have set a record for the third year running. The next stage of the Bridge development is a lavish £25 million new West Stand with 15 millennium suites, 34 boxes, 14, 000 capacity and more than 2, 500 places for meals on match days. The current capacity of 28, 500 will rise to 35, 000 in the 1997/98 season and ultimately 43, 000 when the complex is complete. Clearly, Chelsea are building towards becoming the Manchester United of the South. Captain Dennis Wise said: âWe used to play in front of 13, 000, but this year it has been totally different. It has been 28, 000 every week, and thatâs how it should be at Chelsea. As a result weâre more where we should be as a club.â

Mark Hughes is a man of action and few words. He said: âPerhaps in the past Chelsea hoped to be involved in a competition at their climax. Now we expect to be. Thatâs progress.â

Chelsea Football Club were once synonymous with racism. It was infested by the National Front, the home of soccer bigotry. The Shed was its symbol, a breeding ground and recruitment centre. It was not alone, of course. There were several other terraces in English football plagued with violent and unsavoury fans, whose racism was demonstrated by antics such as throwing bananas onto the pitch and imitating monkey noises.

Chelseaâs few black players were hardly welcome. So, it was hell for black opponents, targeted much to the embarrassment of black and white Chelsea players alike.

Ken Bates presided over years of racial tension. âPaul Cannoville was our first black player and our own fans would throw bananas at him when he warmed up at the side of the pitch. Now we have the first black manager in the Premiership.â Bates battled against racism, and Gullit has helped his campaign. âWith us, it was a question of give a dog a bad name. Yet it was happening at other clubs. Blackburn, for example, never signed a black player; nor did Liverpool for a long time. But donât believe that racism has left the Bridge, it hasnât â it has just been contained. Gullit has had an effect, a marvellous effect, but heâs not the Messiah!â

Maybe not, but his influence is apparent. Fans used to shave their heads in homage to unpalatable and dangerous right-wing groups ⦠now they shave their heads in worship to Vialli.

In his own forthright and inimitable style, Bates discussed the clubâs Big Fish at the Bridge over an exquisite Italian meal of lobster and sea bass at a fashionable Chelsea restaurant, LâIncontro in Pimlico Road. âHoddle bought Gullit, but Hoddle couldnât have bought the players Gullit has! Four years ago we would have been on par with the likes of QPR and Crystal Palace. Hoddle produced that quantum leap by transforming the club into a Little England. Gullit has made it a Little Europe. Gullit has made people realise that English clubs can look beyond the white cliffs of Dover.â

Bates finally got it right in his choice of manager after John Hollins, Bobby Campbell and Ian Porterfield. At the time of Gullitâs appointment he was asked how it felt to be not only starting his first season as manager but also the highest-profile black manager in the English game. There wasnât a flicker of emotion as he responded: âWhether you are black or white, what is important is talent. My father, who studied economics at night school, told me that I would have to work harder than others for what I would achieve. For me, that was the stimulation. I took it positively. I felt proud of who I was, of the colour, everything. Of course, I am aware that Iâm black and that I stand out. But I use it to my advantage. I view it positively. If you feel attacked by your difference, then it is you who has the problem.â

Former Chelsea boss David Webb believes Gullit is destined for the top in management. Webb, still adored by Chelsea fans, is delighted his old club are now FA Cup champions with an eye on winning the league championship in 1997/98. He said: âIf heâs successful here, the really big clubs in Europe will want him. Every move he makes is watched in Europe. Powerful teams like AC Milan will be aware of what he achieves. The biggest clubs want the very best, which is why Cruyff ended up at Barcelona.

âItâs different for English managers. It seems they have to be successful for three or four years at a club before they are considered to be among the best. But in Europe people move about much more. Everythingâs a stage in their career for them. But Iâd love it if Ruud stays at Chelsea for years and really builds something. Itâs great to see Chelsea up there among the best. What the club must do is build over a period of time. Itâs what Iâve set out to do at Brentford and I like to feel weâre reaping the rewards. Thatâs why it pleases me to see youngsters like Morris, Myers and Duberry making an impact at Chelsea alongside the big-money Italian signings.â

Gullit hired Ade Mafe, an Olympic 200-metre finalist and Linford Christieâs former training partner, as fitness trainer. Mafeâs mission was to help the players increase their speed over short distances and to develop their stamina and upper body strength. Gullit saw Mafeâs appointment as helping to address the clubâs failure of not being able to hold onto the lead, which happened on 17 occasions in Hoddleâs final year at Chelsea. The improvement was seen early in the 1996/97 season: Chelsea were stronger in the final 15 minutes than they had been in the previous season and were less likely to make fatigue-induced errors. Gullit said: âWe scored late goals against Middlesbrough and Arsenal and that proved we still had strength at the end of games.â

Mafe had moved into the lucrative world of personal fitness training before being snapped up as part of Ruudâs backroom team. âIt is really good to be back in the elite sporting world again. I feel this is a good challenge and I love a challenge. Iâm working on the playersâ speed off the mark, their leg strength, agility, reaction times and awareness â all things we had to do for athletics that are applicable to soccer.â

But heâs reluctant to take credit for the resurgence in the teamâs fortunes or their vast improvement in the last third of their games. âWhat has happened is down to Ruud and a new era starting. Iâm just a small part of the whole and I want to see the team succeed.â

Ex-Olympian champion and true-Blue fan Sebastian Coe knows Ade well. Both travelled to Los Angeles in 1984 as part of the British Olympic team. âThe science and technique of training in English football has been something thatâs been overlooked for years. Ruud Gullit has recognised that no Continental club would consider training to be something that took place between 10am and midday. I know the Italian set-up well, having lived in Italy for some time, and itâs a full-time 9am to 5pm job with work on technique and conditioning.â Coe points out, though, that athletes have been employed as coaches before in English football training. âNorman Whiteside is one example. He was taught sprinting techniques by Olympic gold medallist Mary Peters. But this is more the exception than the rule. Lessons can also be learned from other sports. If you look at the success of the England rugby union side, it has been based on athletic technique.â

Gullit has effected a Continental-style revolution that started with Ade. Gullit said: âAde has done an excellent job. The players are much fitter now and some go out and do extra work by themselves. Now they understand that if they take care of their bodies then they can last longer in the game.â

Dan Petrescu is used to such methods from Italian football. âAll Ruud is trying to do is to bring Italyâs more professional approach to training to Chelsea. Ade is something new in English football, as he is the first fitness coach in the Premier League. But in Italy the use of fitness coaches is not unusual. Some of the English players were surprised in pre-season how hard the training was. Perhaps they are not used to training as hard as players in Italy. âWe are not horses,â they said. But we should be thoroughbreds, because the games here are so much quicker than in Italy.â

As for Gullitâs transition from player to manager, Petrescu said: âRuudi likes to laugh and joke, but he can also stand apart from us and do what a manager must do. We know he is not happy when we do not play well â even if we win. But he inspires us to play better.â

Gullitâs laid-back manner hides his desire to be as successful a manager as he was a player. Early in the 1996/97 season Dennis Wise said: âWe are all encouraged to put forward our views. He is happy to listen to them. He laughs when we moan but almost always says: âGo out and enjoy yourselves and score some goals.â This is my seventh season at Chelsea. Iâve been in four semi-finals and one final and havenât won anything for my club. Ruudâs attitude is so positive. He wants to win something, and so do I. He makes me believe I will as he does the rest of the team, because he gives us that little bit extra. In fact, this season itâs more than a little bit extra with the players he has bought.â

Chelsea were the original fashionable club of the swinging 1960s. Raquel Welch once sat alongside Dickie Attenborough at the Bridge â there was no trendier place to be seen. Alan Hudson was the all-time crowd favourite, the trend-setter. Alan says Gullit has brought the buzz back to the famous borough of Kensington and Chelsea. âThis is the nearest weâve ever got to the atmosphere of the late 1960s and early 1970s. You can still sense it when there isnât even a game on. The club has been very dour for a long time, but Stamford Bridge now is alight.â

Less than two miles from Heathrow, the worldâs busiest airport, nestles the serene setting of Chelseaâs Harlington training headquarters. In the past, only a handful of journalists would assemble for pre-match briefings. Now the place is constantly under siege. Schoolchildren, families, fans and just the curious swell the ranks of onlookers to catch a glimpse of Gullit and the foreign stars. Youngsters just want to touch Gullit. So many turn up that crash barriers manned by overworked guards who also patrol the pitch are now a familiar sight.

Early in the 1996/97 season Scott Minto said: âThere are so many people who turn up at our training ground that I have had to tell the stewards guarding the entrance that Iâm a player and had to ask them to let me drive in for training. It is amazing really to think that the club has attracted players like Vialli, Zola and Gullit. I wouldnât have thought I would be playing with players like them when I joined from Charlton two years ago.â

One of Englandâs finest-ever imported players, Ossie Ardiles, is now enjoying a managerial renaissance in Japan. He arrived from South America with Ricardo Villa to experience the original culture shock. Back at his Hoddeston home on a break from his managerial successes in Japan, he told me: âI think coming to London is a big advantage for Gullit and his Italian signings. It is a big, big difference living in the capital than living, say, in the north of England. There is a big Argentinian community in London that helped me to settle, and there is similarly a large Italian community in the capital. The cosmopolitan Chelsea area, in particular, is definitely conducive to keeping star foreign players happy.â

Also in the clubâs favour is that Gullit can contend with settling-in difficulties. Having made big international moves he can empathize with his foreign stars and help them to adjust. An added complication, however, is that Chelseaâs culture shock has been two-way. While the Italians have had to adjust, so too have the British players. The bangers and mash brigade, led by that typically chirpy cockney Dennis Wise, have had to alter their eating habits to follow the Continental approach extended from the Hoddle regime. Routine food allergy tests are conducted to examine whether anything has been absorbed into the playersâ bodies that might affect their performance. Erland Johnson was told to steer clear of lager â a big blow for the Norwegian! Ruud has had to cut down on bread, coffee and chocolate, and Jakob Kjeldbjerg was warned off lettuce. Then there is the Frenchman Frank Lebeouf. The new delicacy he brought to the training ground canteen was cornflakes in his cup of tea! Sometimes he eats his breakfast cornflakes with apple juice out of the bowl.

Like others, Minto pinpoints the beginning of Chelseaâs transformation to the date Hoddle signed Gullit. âThings have changed much more since Ruud has taken over. Training has been a little more relaxed â apart from the five-a-sides. We have a fiver a man on those now, so the tackles really fly. But more seriously, this club is going to get bigger still under Ruud. He is such a charismatic player and manager that he will attract the top players from around Europe. You look at his career and he has done everything. If you watch the way he trains and plays, he is a good example. You canât help but learn from him.â

Andy Myers agrees: âOff the field the club has definitely progressed and become more professional. We go for tests to see if we are allergic to any foods. Iâm taking more care of my diet than I was a couple of years ago and I feel fitter thanks to the work Ade Mafe has put in. Weâre becoming 24-hour-a-day professionals in the same way as the Italians.â

Gullit says he found it difficult, at first, to make the transition from player to manager. âIâve had to distance myself because I must make tough decisions. I used to enjoy being part of the locker room. But I knew Iâd have to separate myself from that when I took the job.â Gullitâs methods differ from Hoddleâs, but he refuses to make any comparison. âBefore I took charge I had to sit quietly in the dressing room and suggest changes discreetly. I never knew whether they would be carried out. Now I am right there in the middle, giving talks, holding meetings and showing the players what they are doing right and wrong. Itâs so nice to be able to express my feelings and ideas this way. And you can see from the playersâ faces that they are enjoying what they are doing. They know there is more to the game than just kicking the ball into the box and hoping somebody might score. They have improved as players and they can still do better. My job is not to get a better team in order to chase Manchester United. It is just to get a better team.â