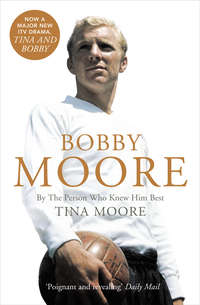

Bobby Moore: By the Person Who Knew Him Best

I wasn’t a total failure. I was picked for the hockey team, showed willing by joining the fencing club and had a very nice English teacher called Miss Mackie, who didn’t seem much older than her pupils. Years later our daughter, Roberta, then 10, won a place at the City of London School for Girls. Bobby and I travelled up to the Barbican with her for her interview and when we were admitted into the Headmistress’s study, there was Miss Mackie! I seemed to grow younger and smaller by the second as I turned into Tina Dean from Christchurch Road with her heel grips and failure to appreciate the finer points of Shakespearean plays.

‘I can only hope Roberta does better than me,’ I faltered.

Miss Mackie looked at Bobby, then nudged me. ‘Oh, I think you did very well, dear,’ she said, with a bit of a wink.

Once it was confirmed that I didn’t have a glittering academic future, my mother decided to get me onto the books of a modelling agency. We went to their headquarters so they could take a look at me and we were waiting to be seen when we overheard the receptionist answering the phone. As she was taking down all the details out loud, we realized that the caller was trying to book one of the agency’s models.

‘Quick,’ hissed my mother and dragged me out into the street, where she hailed a cab and hustled me into it. The next moment, she was telling the cabbie to take us to the address we’d just heard trip off the lips of the receptionist.

When we got there, my mother announced to the client that I was the model sent by the agency. Looking a bit dubious (I was only 15), the client gave me a coat to try on. I did my best, but he received the coat back from me impassively and invited my mother to try it on. As soon as he saw her in it, he offered her the job! I think that was when my mother realized that I wasn’t going to be a star myself, so I’d better aim for the next best thing, which was to marry one.

By that time my mother had been married to Eddie, the ship’s chef, for three years. I was 11 when she first introduced him to me and at the time I liked him. I was still quite innocent and impressionable and it never crossed my mind that he was playing up to me in the hope that I’d accept him, unlike all my mother’s other suitors, which would earn him Brownie points with my mother. I think the fact that I tolerated him where I’d rejected the others probably clinched it for Eddie where my mother was concerned.

When she told me she was getting married, I was so pleased that I immediately started imagining what I’d wear and how I would look with my hair permed in a style called ‘Italian Boy’. But the evening before her wedding, I went to show her my dress, which was white with a floral print and made of paper nylon, and found her crying on the phone to her friend, Sally Lombard.

Although I’ll never know for certain, I’m convinced that she realized she was making a mistake, that she’d only agreed to marry Eddie because she was weary of Joe’s broken promises and because life as a single parent was tough and she longed for a bit of security and support. But Joe was the man she really loved and in any case, Eddie wasn’t as nice as we thought. It was only when he was wooing my mother that he tried to win me over by being as sweet as pie to me. After the wedding, we started to see the other side of him - from sweet as pie to sour as lemons. In the end he took himself off back to sea and that was the last we heard of the Dreaded Eddie.

So when my mother met Bobby, I think she thought, ‘Here’s a decent man.’ She met his parents, Doris and Bob, who had been married for ever. She saw the stable background he’d come from and she wanted that for me. She didn’t want me to re-live her life.

CHAPTER THREE

When Bobby Met Tina

My mother and I used to walk past Ilford Palais on the way to the Regal cinema and I’d look yearningly at it and think I’d never be old enough or glamorous enough to go there.

On the ceiling was a glittering, twinkling ball of mirrored mosaic, spinning and throwing off lights. The girls would put their handbags on the floor and dance round them. The cha-cha was the fashionable dance and there would be a long trail of boys and girls doing it in sync, like line-dancing. I used to think it was so adult and I longed to be part of it.

There was a Babycham bar. Babycham was the drink du jour; it was sparkly and bubbly like champagne, although actually it was made from pears. It came in tiny bottles with a Bambi on the label blowing bubbles from its mouth. You drank it from a proper champagne glass, feeling like sophistication come to life.

The Palais was packed with young people. It featured live bands like Ambrose and his Orchestra. A man called Gerry Dorsey sang with the band, but failed to achieve any great fame until he recorded a song called ‘Please Release Me’ and simultaneously had the inspired idea of changing his name to Engelbert Humperdinck.

Another of Ambrose’s singers was Kathy Kirby. She looked like Marilyn Monroe, with fabulous platinum blonde hair and glossy red lipstick and a soaring soprano voice. In the early Sixties she went on to have a huge hit called ‘Secret Love’, but in those Ilford days she and her sister, Pat, lived virtually opposite us. I’d see her in the window of her front room, wearing a satin cat suit and walking around holding the phone on a very long wire, which to me was the height of chic. Pat was quite something, too. She married Terry Clemence, who owned the Seven Kings Motor Company, and they had three daughters who all went on to make brilliant marriages, one to a viscount, the other two to lords. Not bad going for three car dealer’s girls from Essex.

I wasn’t to know then, but Pat and Terry would one day become near neighbours of Bobby and me in Chigwell. We lived it up at many a party. But that was all years into the future . . .

The big day came when I finally made it to the Palais. I’d been off school with flu since the start of the week and my mother had been trying to build up my strength with nourishing invalid breakfasts of bread in warm milk with sugar before she headed off for work. Towards the end of the week I started feeling better and concocted a plan with a school friend, Vivien Day, to go to the Palais for the lunchtime session. This started at twelve and as my mother didn’t get back from work until early evening, I knew I could get back home and into my sickbed without her being any the wiser.

That morning she treated me to the bread-and-milk as usual. Yuk. Who wants that when you’re heading for the Babycham bar? She was really worried because I only picked at it, and to tempt back my appetite left me Irish stew, my favourite, for my lunch.

The stew went untouched. Instead, Vivien and I were tremblingly shelling out 6d. each at the door of the Palais. Sixpence was the lunchtime cheap rate. In new money, it translates into the staggering sum of 2½p.

My heart was beating like a hammer as I advanced into the place that I’d dreamed of for so long. I just looked and looked. It was crowded with people of my own age, most of whom had nipped out during school lunch hour. I was particularly awestruck by the ladies’ cloakroom. The walls were panelled in rich, plum-coloured velvet. The fittings were gilt. It was lit by chandeliers. I was amazed.

When I got home, still starry-eyed, my mother was waiting for me. I’d forgotten that Thursday was her half-day. The lamb stew was thrown straight into the dustbin. As far as she was concerned, it was the most heinous thing I’d done since getting myself flashed at in Valentine’s Park. It was boarding school for me again, for all of twenty-four hours.

The Ilford Palais episode wasn’t my only covert expedition. I used to sneak up to the Two I’s with my girlfriends to see Tommy Steele, but things would hardly have started before we had to steal away at 10 pm like Cinderella. Another place we went to was Heaven and Hell, which was in a basement accessed only by some very narrow stairs. If a fire had broken out, it would have been virtually impossible to escape. But you never think of that kind of thing when you’re 15. You’re immortal.

My first boyfriend was Harry and I went out with him for six months. He was 17 and had lovely amber-coloured eyes with long eyelashes. Harry was a Mod and wore a bum-freezer jacket; he took me to haunts like the Skiffle Parlour in Ilford Lane on the back of his scooter. But that Easter I was offered a school trip to Perpignan, and my mother said, ‘I think it would be a good idea if you went on that.’ She had no time for Harry, amber eyes or not.

No sooner had she removed me from the clutches of Harry than I fell for Gilbert, the Perpignan Adonis. He played rugby for France schoolboys and was my first real crush. Cupid’s dart must have been more of a pinprick, though, because Gilbert was soon abandoned in favour of my next conquest, an actor. He can’t have been a very successful one because I’ve forgotten his name. But he had some great lines. ‘When you grow up,’ he murmured, ‘you’re going to be quite something. You must always drink champagne with a peach at the bottom of the glass.’

My suitors also included the one who arrived to pick me up in a Jag. The Jag was nearly as old as he was. When he knocked on the door, my mother opened it and said, ‘Can I help you?’

‘I’ve come to see Tina.’

My mother said, ‘Do you know how old she is? Fifteen.’

‘Well, I like them young.’ Off he went, never to be sighted again.

And then came Bobby.

‘Blue Moon, you saw me standing alone

Without a dream in my heart

Without a love of my own.’

It’s true. It really happened that way. The band at the Ilford Palais was playing ‘Blue Moon’ and suddenly this blond boy was in front of me, asking for a dance. Bobby always had an incredible knack of staging things to perfection.

To him, I suppose, I was a pretty girl in a lovely dress. Pat Booth, who went to the Palais at around the same time as me, said she’d catch sight of me in a boat-necked long-sleeved number and feel deeply envious - which was funny, because I used to lust after her clothes, a ‘mod’ dress, bell-skirted, with cap sleeves. I discovered later that she also went out at one point with Harry the Mod; it must have been those amber eyes. After that she went out with one Billy Walker, who was a bouncer at the Palais, though not for much longer. He was just passing through on his way to becoming the golden boy of British heavyweight boxing

Bobby would go to the Palais with some of his fellow apprentices from the West Ham ground staff. Much later I found out that he’d been watching me for weeks, stationed on the balcony but too shy to approach me. What did Bobby see in me? I spoke nicely, I’d led a sheltered life and my mother had groomed me to the best of her ability. All those elocution lessons, dancing lessons and my grammar school education had combined to turn me into what, in the late Fifties, was called ‘a nice type of girl’. I’m not sure that the fencing lessons ever came in useful, but my sense of humour did. I could make him laugh and this intense, rather inhibited football prodigy needed that.

Once you’re in a relationship, you get to know and trust the other person and then your real self starts to unfold. Bobby unfolded a lot. Even now, I have a very strong image of him as a teenager, just sitting watching me, laughing because I amused him. I was the extrovert of the partnership and that’s what he enjoyed about me. I brought him out of his shell. I could always twist things to see the funny side and although Bobby projected a public image of self-control and aloofness, he actually had a very dry wit. It was so subtle that unless you were completely attuned to him, you missed it.

When we met, I was coming up to my sixteenth birthday. He seemed a bit square at first. Because I’d grown up in such a female-dominated environment, I knew nothing about football. I wasn’t at all impressed that Bobby was a player, let alone that he had just signed professional forms with West Ham and was an England Youth international. I didn’t even realize he was a footballer at first, not a proper one who was planning to make a career out of the game.

His great heroes were Johnny Haynes, captain of England, and the Manchester United icon, Duncan Edwards, with whom he was besotted. I hadn’t a clue who he was talking about - didn’t even realize that Duncan Edwards, one of the Busby Babes, had died along with seven of his team-mates earlier that year in the Munich air crash. Duncan had been a left-half and was already established in the England side, despite his tender age. Bobby was shattered when he heard the news.

He was much more taken with me than I was with him in the early stages. After that first dance I agreed to meet him at the Palais the following Saturday - then I stood him up. He waited all evening for me.

I’d told him I liked going to the record store, so he took to lurking around there in the hope that I’d walk in, but the most he would get from me was a little nod of acknowledgement. Even so, something about him must have made an impression because I told my mother about him. That was when Fate took a hand. One day, my mother and I were sitting in the back of a taxi as it crawled along Ilford High Street in the traffic when I happened to glance out of the window. There he was, sitting in a coffee bar. ‘That’s him!’ I exclaimed. ‘That’s the boy who asked me out.’

My mother leaned across me to get a better view. ‘Mm, he looks nice,’ she said. ‘Why don’t you invite him home for tea?’

Our first date took place the evening after his second game for the West Ham first team. Bobby had made his first team debut at Upton Park when West Ham, newly promoted to the top flight, had beaten Manchester United 3-2. Bobby, only brought into the side because senior players were unfit, had been brilliant. He dominated the following day’s back page headlines.

It was actually a bitter-sweet moment for Bobby when he got his first team chance, because his rival for the Number Six shirt was Malcolm Allison, who had been Bobby’s mentor and idol since Bobby joined the club as a schoolboy. For most of 1958, they had both been fighting to get out of the reserves, Bobby because he was knocking on the door to his future, Malcolm because he was trying to prove he could still play after a spell in a sanatorium recovering from TB.

Malcolm was thirteen and a half years older than Bobby. Very tall, big-shouldered and handsome, he was a man, whereas Bobby was a boy. He had a slightly sardonic air and sometimes he could be cutting. It would be a while before he developed his twin reputations as fedora-wearing, cigar-smoking playboy and brilliant, flamboyant, big-spending coach, but even then he had panache. More than that, he could tell greatness in the raw. As one of thirteen colts on the ground staff at Upton Park, Bobby had been widely regarded as ordinary, but Malcolm saw something in him that others at the club didn’t and set about coaching him. For that alone, Bobby adored him.

So Bobby’s first-team debut brought mixed feelings. He was thrilled, but sorry it had happened because of Malcolm’s illness. Malcolm, for his part, didn’t bear a grudge. Bobby was his favourite son. Who better to replace him?

Five days after Bobby’s dream debut, the complete opposite happened against Nottingham Forest. He had a terrible game, with the huge crowd shouting to the Forest players, ‘Play on the left-half, that’s the weak link.’ West Ham lost 4-0. Bobby bought an evening paper at Nottingham station and the report on his performance was so damning that he tore it up. He hadn’t any inkling that the last thing I’d be interested in was the football results.

Anyway, I had my own cross to bear. Having spent all afternoon preparing for our date and having my hair specially set for the occasion, I went to meet him at King’s Cross. In those days it was a sooty Victorian edifice with iron gates controlling access to the platforms and huge steam engines fuelled by coal. When I heard the familiar grinding of the wheels and saw Bobby’s train chugging to a stop, I decided to position myself where the steam gently wafted from the engine. I had visions of the mist slowly lifting and me emerging like the mysterious heroine of a romantic movie into a bedazzled Bobby’s path. Sadly, that was not to be. The steam had other ideas and I came out looking like orphan Annie, with the hair that had been so carefully coiffed hanging limp and damp round my forlorn face.

I did think Bobby was great-looking, of course. He didn’t have spots - well, occasionally a couple, but only very, very small ones. He was a terrific dancer; whatever he did, he had to be Mr Perfect. We used to kiss in time to the music. It was heady stuff! Looking back, though, it was so innocent.

The reason I found him a bit square was probably that he’d led a very disciplined life compared to most boys in the Fifties. He and the amber-eyed Harry were around the same age, but Bobby seemed not much more than a baby, really.

Doris was the dominant figure in the Moore marriage and in Bobby’s childhood, and she was fiercely protective of him. She called him ‘My Robert’. She was a very strong character and I think she recognized a similar strength in me. It was a while before we had a relaxed, easy relationship. In contrast, I got on immediately with Bobby’s dad, Big Bob. He was a gas-fitter and came from Poplar. He was much more Cockney than Doris, was prematurely bald and liked clowning around and wearing silly hats. His childhood had been tough - he lost his father in World War One - but he was a lovely, kind man with a wonderful twinkle in his eye. He was straight-talking with it, though. He would tell you if he thought you were wrong.

In some ways Doris, who was always known as Doss, was a bit of a rebel by her family’s standards. Most of them were Salvation Army. They used to go out on a Sunday carrying the Good Book, singing the hymns and wearing the bonnets - the whole ten yards, in fact. Maybe Doss started off by going with them but decided it wasn’t for her - she was an independent-minded individual. Even so, she and Big Bob were very upright, God-fearing people.

Their terraced house in Waverley Gardens had a front fence where Big Bob always chained his bike. The first time I stayed round there, I was put in the box room. Doss cornered me there. ‘Any girl,’ she said, ‘who gets My Robert into trouble will have me to deal with.’

My mother was absolutely furious when I told her. Floored, livid and silent with rage. But she soon recovered her powers of speech. ‘You weren’t brought up to be a floozy!’ she gasped.

She was right. I was an innocent. Bobby and I did our courting in the pre-pill era. A girl I had been to school with died after a back-street abortion. I read about it in the local paper and felt horrified and frightened. But Doss’s words hung over me. I never got Her Robert into trouble.

Neither Doss nor Big Bob smoked or drank alcohol and Bobby realized that my mother was much more worldly and sophisticated than them. When the time came for him to introduce them to the mother of the girl he loved, he bought gin and wine for them to serve. Meanwhile, my mother had realized that Doss and Bob Moore were teetotallers. Wanting to make a good impression, she said, ‘I’d love a cup of tea’ when Doss asked her what she would have.

Equally beside herself to impress, Doss came back with, ‘Cow’s milk, sterilized or condensed?’ It became a running joke between Bobby and me whenever anyone asked what we’d like to drink.

Actually, Doss could never accept that Bobby could put away a lager or four. If he’d had too many, she’d say he was ‘under the weather’. Quite a few years later, one Christmas after Bobby and I were married, he and a lot of the other West Ham lads went out at lunchtime to celebrate the festive season. Christmas Eve always seemed to be a bit of a nightmare for me. There’d been a couple of times earlier when the turkey, West Ham’s annual Christmas present, would go walkabout instead of coming home. Each time it would be spotted sitting on the bar, with Bobby ordering a lager for himself ‘and a gin and tonic for the bird’. They’d eventually find their way home with the turkey propped up in the front seat.

On this particular occasion, Bobby and I were due to go to a function in the West End that night but by mid-afternoon, when he and the turkey still hadn’t made it home, I began ringing round all his known haunts. Eventually I tracked him down to the Globe in Stepney and reminded him about the function.

‘I’ll be home in twenty minutes,’ he said.

I waited for an hour, then rang again. ‘Don’t worry,’ said my increasingly merry husband, ‘I’ll finish my drink and be on my way.’

So I waited another hour, then rang again. ‘If you don’t come home right now, I’ll tell your parents to come and get you,’ I said.

Even that didn’t flush him out, so I carried out my threat. Doss and Big Bob duly set out for the Globe, where they advanced on him from the rear. Doss laid a hand on his shoulder and said, ‘Home, son.’

‘Mum,’ said Bobby as they escorted him out, ‘I’m 31.’

Doss turned and said to the assembled company, ‘He isn’t usually like this, you know. He’s been under the weather lately.’

Bobby was their only child, and Doss and Big Bob adored him. He was Mr Perfect, their reason for being. The only bad thing he’d ever done was pee in a milk bottle - disgusting! Doss was involved in everything Bobby did, from supporting him at every single match he played in to washing, bleaching and scrubbing his laces with a nailbrush to make sure they stayed sparkling white, then ironing them.

It was Big Bob and Doss who took me to Upton Park for my first visit. I’d never been to a match before and I couldn’t believe the number of people there. We sat in D Block with all the other players’ families, behind the Directors Box, and Doss barely took her eyes off Bobby the whole game. She kept shouting, ‘Unload him! Unload him!’ I thought it was a technical term.

Doss had been very pretty as a girl; she’d won a beauty contest and you could see who Bobby got his looks from. Our daughter, Roberta, has inherited her lovely nose. And she was a very good woman: unaffected, modest, generous to those she loved, and natural. But she was a Scorpio and a typical one in some ways. She would harbour grudges. If anyone said anything bad about Her Robert, that would be it for them. They’d be completely cut out, for good and all time.

It wasn’t just her looks that were handed down to Bobby. A lot of his personality traits, like his repressed, uptight side, came from her, too. They were both strict with themselves, both terribly disciplined, almost obsessively immaculate. Even after a late, lager-fuelled night, Bobby would get a clothes brush out and brush his whole suit down before turning in. Everything he did had to be faultless, and that was his mother’s way too.

She used to cut and edge little ‘Vs’ in the side of his shorts just the way he liked them, so naturally when I leapt onto the scene I decided that that was going to be my job from then on. The first time I did it, they split all the way up to the waist during a match, so the first time was also the last. Doss got her job back. My Vs just didn’t cut the mustard.

I also discovered she was a wonderful knitter, so I embarked on making Bobby a hideous green V-neck sweater. I did aspire, but she set such a terribly high standard. Whenever I ate round at Waverley Gardens, she would serve the mashed potato in exact half-moon shapes, using an ice cream scoop. The cuffs and collars of Bobby’s shirts were always as smooth as glass. She’d never rush anything as crucial as the ironing. But as I’ve said, she and Big Bob were good people, and Doss was a little wounded and put out when Bobby fell in love with me. She felt he’d excluded her from his life. But again, that was Bobby - he only ever had one passion at a time. He met me and that was it. He was absolutely besotted.

Bobby also realized that his mum was possessive and he rebelled against that to a certain degree. It wasn’t that he cut any ties with his parents. Once we were married, we constantly went round on visits. He was never derogatory about them. It was just that the intimacy, the sense of having one single, special person you shared your world with, had been transferred to me. He shut off from Doss emotionally. It must have hurt.