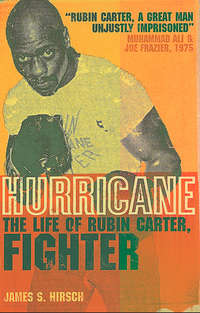

Hurricane: The Life of Rubin Carter, Fighter

For all the confrontations between father and son, Rubin noticed that he liked to do many of the same things as his father. While his two brothers and four sisters often begged off, Rubin hunted with his father and accompanied him on trips to the family farm in Monroeville, New Jersey. His mother told him that his father was hard on him because Lloyd himself had also been a rebel in his younger days. Now, the father saw himself in his youngest son.

That did not become clear to Rubin until he was in his twenties, when he and his father went to a bar in Paterson where the city’s best pool shooters played. As they walked in, the elder Carter quipped, “You can’t shoot pool.”

A challenge had been issued. Rubin considered himself an expert player, and he had never seen his father with a cue stick. Indeed, Lloyd hadn’t been on a table in twenty years. They played, betting a dollar a game, and Lloyd cleaned out his son’s wallet.

Rubin, shocked, simply watched. “Where did you learn to play?” he asked.

“How do you think I supported our family during the Depression?” his father replied. “I had to hustle.”

Unknown to his children, Lloyd Carter had been a pool shark, and his disclosure seemed to clear the air between him and Rubin. “Why do you think I always beat on you?” Lloyd said later that night. “You wouldn’t believe how many times your mother said, ‘Stop beating that boy, stop beating that boy.’ But I saw me in you.” Lloyd Carter had also rebelled against authority, and he knew that was a dangerous trait for a black man in America. “I was trying to get that out of you,” he told his son, “before it got hardened inside.”

It was too late, however. Rubin’s defiant core had already stiffened and solidified.

For all the turmoil in his youth, Carter actually fulfilled one of his boyhood dreams: he wanted to join the Army and become a paratrooper. In World War II the Airborne had pioneered the use of paratroopers in battle. It was not, however, the division’s legendary assaults behind enemy lines that captivated Carter. Nor was it the Airborne’s famed esprit de corps or its reputation for having the most daring men in the armed forces. Carter liked the uniforms. Even as a boy he had a keen eye for sharp clothing, and he admired the young men from Paterson who returned home wearing their snappy Airborne outfits: the regimental ropes, the jauntily creased cap, the sterling silver parachutist wings on the chest, the pant legs buoyantly fluffed out over spit-shined boots.

By the time Carter enlisted, however, the uniform was not his incentive. At seventeen, Carter escaped from Jamesburg State Home for Boys, where he had been serving a sentence for cutting a man with a bottle and stealing his watch. On the night of July 1, 1954, Carter and two confederates fled by breaking a window. They ran through dense woods, along dusty roads, and on hard pavement, evading farm dogs, briar patches, and highway patrol cars. Carter’s destination was Paterson, more than forty miles away. When he reached home, the soles on his shoes had worn off. His father retrofitted a fruit truck he owned with blankets, and Rubin hunkered down in the pulpy hideaway while detectives vainly searched the house for him. Soon Carter was shipped off to relatives in Philadelphia. He decided, ironically, that the best way for him to hide from the New Jersey law enforcement authorities was by joining the federal government—the armed forces. With his birth certificate in hand, he told a recruiting officer that he was born in New Jersey but had lived his whole life in Philly. No one ever checked, and Rubin Carter, teenage fugitive, was sent to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, to learn to fight for his country.

Carter was no patriot, but soldiering allowed him to do what he did best: wield raw physical power. The Army, in some ways, was similar to Jamesburg, the youth reformatory. Carter lived in close quarters with a group of young men, and he was told what to do and when to do it. Individual opinions were forbidden; and just as a reformatory was supposed to correct a wayward youth, the Army was supposed to turn a civilian into a soldier. Carter spent eight grinding weeks in basic training, followed by eight more weeks to join the Airborne. He was then sent to Jump School in Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Recruits were known as “legs,” because graduates received their paratrooper boots. Each class began with about 500 would-be troopers; as few as 150 would graduate. The school’s relentless physical demands thinned the ranks, as recruits were eliminated by the early morning five-mile runs, the pushups on demand, the pullups, the situps, the expectation to run everywhere while on the base, even to the latrine.

Most difficult of all, however, trainees had to learn to leap twelve hundred feet from a C-119 Flying Boxcar. To prepare, they hung from the “nutcracker,” a leather harness suspended ten or fifteen feet aboveground. They lay on their backs strapped to an open parachute while huge fans blew them through piles of sharp gravel until they were able to deflate the chute and gain their footing. There was also the “rock pit.” Soldiers stood on an eight-foot platform, jumped into the air, and did a parachute-landing fall onto the jagged bed of rocks. They then got up and did it over and over again until ordered to stop. To quit was tempting, but the Army sergeants and corporals who ran the Jump School gave those who faltered a final dose of humiliation. They were forced to walk around the base with a sign on their shirt that read: “I am a quitter.”

To Carter, Jump School was “three torturous weeks of twenty-four-hour days of corrosive annoyance.” But when he executed his first jump, he excitedly wrote home about it, flush with pride, and later described the sensation.

There was no time for thought or hesitation. I could only hear the dragging gait of many feet as man after man shuffled up to the door and jumped, was pushed, or just plain fell out of the airplane. The icy winds ripped at my clothing, spinning me as I hit the cold back-blast from the engines, and then I was falling through a soft silky void of emptiness, counting as I fell: “Hup thousand—two thousand—three thousand—four thousand!” A sharp tug between my legs jerked me to a halt, stopping the count, and I found myself soaring upwards—caught in an air pocket, instead of falling. I looked up above me and saw that big, beautiful silk canopy in full blossom and I knew that everything was all right. The sensation that flooded my body was out of sight! I didn’t feel like I was falling at all; rather, the ground seemed to be rushing up to meet me.

The ground, however, gave Carter a jolt of reality. Even though the armed forces had officially been desegregated under President Truman, racial segregation and inequality still prevailed. Riding a train from Philadelphia to Columbia, South Carolina, black soldiers were shoehorned into the last two cars while whites rode in relative comfort in the first twenty-odd vehicles. When paratrooper trainees were bused from South Carolina to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, passing through Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee, blacks sat in the back of the bus. At dinnertime, whites ate at steakhouses while blacks had to stay outside and eat cold baloney sandwiches and lukewarm coffee.

This experience pricked Carter’s racial consciousness for the first time. Whites and blacks had mixed easily in his old neighborhood in Paterson, and while Jamesburg State Home segregated the inmates, Carter assumed that whites slept in their own quarters because they were weaker than blacks and therefore vulnerable in fights. But as his bus rolled through mountainsides of quaking aspens, he saw white farmers guzzling beer at resting stops, their drunken rebel shrieks grating his nerves. Their pickup trucks carried mounted gun racks, and they eyed the black soldiers suspiciously. Carter suddenly realized why his father and uncles drove their families through the Deep South in caravan style. He had thought it reflected the family’s solidarity, but he now understood that it was to provide safety in numbers. He felt angry that his parents had not told him about the true dangers that lay across the land—in the South and throughout the country. This discovery came at the very moment Carter was training to fight for America. He decided from here on he would defend himself in the same fashion that he was defending his country—with guns. If his adversaries, be they communists or crackers, had weapons, so too would he. Carter kept these thoughts to himself, however. Speaking out was not his style. But his silence, about race and all other matters, would soon end.

By the time the winter winds blew through Fort Campbell in 1954, the 11th Airborne was preparing to transfer to Europe. Carter was one of three hundred paratroopers recruited from the States to be part of the advance party. Their destination: Augsburg, Germany. Founded almost two thousand years ago, Augsburg is one of those languorous Bavarian towns that lolls in the shadows of its history. Grand fountains and tree-shaded mansions with mosaic floors evoke a golden age of Renaissance splendor. In the Lower Town, among a network of canals and dim courtyards, small medieval buildings once housed weavers, gold-smiths, and other artisans. Nearby is Augsburg’s picturesque Fuggerei, the world’s oldest social housing project that still serves the needy. Built in 1519, it consists of gabled cottages along straight roads and preaches the maxim of self-help, human dignity, and thrift.

But Augsburg’s patrician munificence and cobblestone alleys were far removed from the fervid world of Private Rubin Carter. He spent most of his time on the Army base, a member of Dog Company in the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment. Each day began at 6 A.M. with an hour’s run on the cement roads surrounding the compound. Even on the coldest winter mornings, Dog Company ran in short-sleeve shirts, their frozen breath from shouted cadences hanging in the Augsburg air.

“Hup-Ho-o-Ladeeoooo!” the sergeant yelled.

“Hup-Ho-o-Ladeeoooo!” the Dog Company echoed.

“Some people say that a preacher don’t steal!”

“Hon-eee! Hon-eee!”

“Some people say that a preacher don’t steal—but I caught three in my cornfield!”

“Hon-eee-o Ba-aa-by Mine!”

Military maneuvers on the steep hills around Augsburg were a weekly exercise. The soldiers clambered up and down the slopes in leg-burning labors, firing blank bullets to secure a hill or to push back an imaginary enemy. But Carter learned what the real nemesis was on his first maneuver.

“Oh shit!” someone yelled. “It’s comrades’ ‘honey wagons.’”

A fetid smell swept across the hills. On nearby cropland, farmers took human excrement from outhouses, slopped it in honey wagons, and spread it across their potato and cabbage fields. There was no defense against this invasion, but Carter never complained. Shit, the stench inside prison is worse.

Carter attended daily military classes in the “war room,” where maps of the European terrain hung on the wall and the platoon’s weapons were stored. He studied heavy weapons, rifles, and mortars, memorizing their firepower. Carter trained as a machine gunner; his job would be to back up the front line.

He liked the rigors and responsibilities of Army life, but his early days in Augsburg were marked by isolation and loneliness. His stutter, as always, deterred him from reaching out to others. He was also afraid that the Army would discover the deceptive circumstances of his enlistment and that he was a wanted man in New Jersey. Best to keep a low profile, he figured. So he never spoke up in class, he ate alone in the mess hall, and he rarely socialized at the service club, where friendships were forged over watered-down beer and folds of cigarette smoke. On weekends, he took the military bus to Augsburg. The town had an aromatic blend of fresh bread, spicy bratwurst, and heavy beer, a piquant scent that would hang on the soldiers’ leather jackets long after they returned to the States. Augsburg’s horse-drawn wagons and pockmarked buildings from a 1944 air raid added to the town’s quaint and battered charm; but for most soldiers, its attractions were the liquor and the women. At one restaurant, each table was equipped with a telephone so that male patrons could ring nearby ladies of the evening and request a date.

Carter, however, rarely socialized and did not stray far from Augsburg’s Rathausplatz, the town square. He had no special interest in its statue of Caesar on an elaborate sixteenth-century fountain. He simply was afraid he would be stranded if he missed the bus home.

The Airborne troops conducted weekly practice jumps in a nearby drop zone. One morning, after falling from the sky, Carter was folding his parachute when he heard a strange voice from over his shoulder.

“How you doin’, little brother?”

Carter looked up but said nothing. A man he had never seen before had landed within twenty yards of him, but the close touchdown did not appear to be accidental.

“I’ve been watching you,” the strange man said, “and I think you’ve got a problem.”

“W-w-what’s that?” Carter demanded, stunned by the stranger’s effrontery.

“We’ll talk about that later,” the stranger said. “Let’s go back to the base.”

Ali Hasson Muhammad was unlike anyone Carter had ever met. A Sudanese Muslim, Hasson had immigrated to America and was now trying to earn early citizenship by serving in the Army. He wanted to give Carter guidance as much as friendship. With braided hair that wrapped around his head and a shaggy beard, he was like a sepia oracle. While other authority figures in Carter’s life—his father, reformatory wardens, Army sergeants—had lectured him, Hasson spoke in parables designed to redefine Carter as a black man.

Walking back to their barracks one night, Hasson told Carter how a fat countryman from Sudan fell asleep while shelling peas in the attic of his cramped hovel. “The hut mysteriously caught on fire, and the village people rushed in to save the farmer,” he said. “But they couldn’t do it, because the man was too fat and the attic too small to maneuver him over to the stairs. The townsmen worked desperately, but without success, to save the man before it was too late. Then the village wise man came upon the scene and said, ‘Wake him up! Wake him up and he’ll save himself!’ ”

Black Americans were also asleep, Hasson told Carter, and they would have to wake up to save themselves. Hasson was a slender man who spoke softly and worked as a clerk because he refused to carry a weapon. But his dark, glaring eyes conveyed the passion of his beliefs. “Nobody can beat the black man in fighting, or dancing, or singing,” he told Carter. “Nobody can outrun him or outwork him—as long as the black man puts his mind and soul to it.” Tears of frustration welled in Hasson’s eyes. “What on God’s earth ever gave the black man in America the stupid, insidious idea that white men could out-think him?”

Carter heard Hasson’s ardent pleas but never really absorbed them. What does this have to do with me? He didn’t understand some of Hasson’s more opaque sermons and euphemisms, and he had trouble believing Hasson’s thesis of black superiority. What evidence was there in his own life to prove such a claim?

The evidence soon surfaced a half mile from Carter’s barracks. The Army’s Augsburg fieldhouse, with a sloped quarter-mile track, a basketball court, and weight machines, was the social and athletic epicenter of the base. Even on nights when frost covered the ground, the creaking gym retained a muggy, pungent atmosphere from the men’s concentrated exertions.

Carter rarely entered the fieldhouse. But after pouring down a few too many beers at the service club one night, he and Hasson took a shortcut through the gym. There, they were stopped cold by what they saw—prizefighting. The 502nd regimental boxing team was in training, and the drills seemed to produce their own wonderful soundtrack: the staccato beat of speed bags, the plangent thuds of fists against heavy bags, the testosterone snorts of determined fighters. Carter and Hasson watched for a good while.

“Shit!” Carter said suddenly. “I-I-I can beat all these niggers.” Hasson looked at him in disdain. “I can see why you don’t open your mouth too much,” he said. “Every time you open it, you stick your foot right in it. So why don’t you just finish the job and tell that gentleman over there what you’ve just told me. Maybe he can straighten you out.”

Hasson motioned to a young, ruddy-faced coach named Robert Mullick, whose blond hair was sheared so short you could see the pink of his skull. His blue eyes sparkled as he reviewed the boxers working out. The boxing ring was the Army’s surrogate battlefield, where champions were wreathed in glory, and the boxing coach trained his men to show no mercy. “Lieutenant?” Hasson said, grinning. “My little buddy thinks he can fight. In fact, he honestly feels that he can take most of your boys right now. So he’s asked me to ask you if you could somehow give him a chance to try out for the team.”

Mullick looked over Hasson’s shoulder at Carter, who suddenly felt his silver parachutist wings hanging heavily on his shirt. Paratroopers were known as a cocky crew, often boasting that one of them could do the work of ten regular soldiers. They were also disliked for another reason: they received higher pay than the GIs, driving up the price of prostitutes.

Now Carter thought his parachutist wings were like a bull’s-eye, signaling to the grim lieutenant that this was his chance to teach at least one saucy trooper a lesson. “So, you really think you can fight, huh?” Mullick asked. “Or are you just drunk and you want to get your stupid brains knocked out? Is that what you want to have happen, soldier?”

Carter’s first reaction was to do what he always did when someone challenged him: knock him down, teach him some respect, show him he wasn’t to be meddled with. But he held back his fists if not his lip.

“I-I-I can fight—I can fight,” Carter stammered. “I’ll betcha on that.”

“You will?” Mullick said, a grin creasing his face. “Well, I’m going to give you a chance to do just that, but not tonight. You’ve been drinking, and I don’t want any of my boys to hurt you unnecessarily. Just leave your name and I’ll call you down tomorrow. Maybe by then you won’t think you’re so goddamn tough.” He turned his back to Carter; the conversation was over.

The next day Carter lay in bed, petrified. He had always been a streetfighter, and a good one at that. His gladiator skills had earned him the position of “war counselor,” or chief, of his childhood gang. War counselors negotiated the time and place of rumbles between gangs, but sometimes they agreed to fight it out between themselves. Carter always relied on “cocking a Sunday,” or slipping in a wrecking ball of a punch when his opponent wasn’t expecting it. He didn’t know how to move around a boxing ring, to counterpunch or to tie up, and his chances of cocking a Sunday on a skilled fighter seemed impossible.

But Mullick was not about to let Carter off the hook. His drunken challenge was a slur against Army boxers, and now he would pay for it. Through a company clerk, Mullick ordered Carter to report to the fieldhouse. When he arrived, the arena was abuzz. Prizefighting was a big sport in Germany, and the impending fight had attracted droves of Army personnel, including sportswriters from Stars and Stripes, the Army newspaper. It seemed that the dismantling of a brassy parachute jumper would liven up an otherwise slow day in the Cold War.

Carter stood unnoticed in the doorway, watching two fighters in the ring hammer each other. The short dark fighter was bleeding from a gash over his eye. The other fighter seemed to be suffocating from his smashed nose, spitting out gobs of blood from his mutilated mouth. The crowd stood, cheered, roared for more mayhem, indifferent to who was winning or losing as long as someone toppled over. Carter knew he was out of his class.

When the bout was over, Mullick jumped down from the apron—he had officiated the fight—pushed through the crowd, and found Carter. “Are you ready for that workout now, mister?” Mullick asked. “Or do you have a hangover from boozing it up too much last night and want to call it off?” Carter shook his head.

The lieutenant nodded, wheeled around, and strode back toward the ring, where his fighters were clustered. Carter admired the sweaty black faces. They were scarred and ring battered, but they seemed to have a closeness about them that transcended their ebony surface. They were men of great courage, Carter thought. You’d have to shoot them to stop them, for their pride and integrity couldn’t be broken.

Finally, breaking away from the squad and climbing into the ring was a large boxer with a sculpted chest and stanchions for legs. He shook out his arms, flexed his ropy muscles, and shadowboxed in a glistening ritual. I have to admit, the nigger looks good, Carter thought.

The mob of spectators jumped to their feet and shouted their conqueror’s name. He was Nelson Glenn, six feet one inch of animal power, the All-Army heavyweight champ for the previous two years. Mullick climbed through the ropes and began lacing on his fighter’s gloves. At the same time, he motioned Carter to enter the ring. It was too late to back out, so he climbed in, Hasson on his heels.

Carter felt the adrenaline pump through his stout body and he showed no fear. He felt light on his feet but also strong, resolute. He was not going to flinch, to back down, to quit. He felt a sharp, electrifying twinge of self-respect. Nelson Glenn will have to bring ass to get ass. But he also felt the loneliness, the vulnerability, of the boxing ring. There was no escape.

Hasson tied on Carter’s liver-colored gloves and offered some counsel. “Stay down low, and watch out for his right hand,” he whispered softly. “And try to protect yourself at all times.” Carter nodded.

Mullick called both fighters to the center of the ring to explain the ground rules, but he spotted a problem with Carter. Like Glenn, Carter wore his standard green Army fatigues (long pants, shortsleeve shirt) and tight Army cap, but Mullick pointed to Carter’s shoes. “What are those?” he asked.

“My boots,” Carter said.

Mullick rolled his eyes. “What size shoe do you wear?” he asked.

“Eight and a half,” Carter responded.

“You need boxing shoes,” Mullick said, more in pity than disgust. He fetched a pair from one of his own boxers and Carter sheepishly made the switch. Now he was ready.

The bell rang.

Glenn came out dancing, jabbing, grunting, contemptuous of this no-brain, no-brand opponent who presumed to step into the ring with the champion. Carter tried to stay beneath his crisp left hand, pursuing his adversary like a cat in an alley fight. Carter bobbed, feinted, ducked, then lashed out with his first punch of the fight—a whizzing left hook that caught Glenn flush on his chin, spilling him to the canvas. The blow may have startled Carter as much as Glenn.

Glenn bounced up quickly but was now groggy. He was surprised by the power of a mere welterweight. Carter returned to the attack and bored in with a quick, crunching left hook, then another, then a third, the last shot sending Glenn’s mouthpiece flying out of the ring. Nelson’s eyes turned glassy, his arms fell limp, and he started sinking softly to the canvas. Carter realized he could hear himself panting; the crowd was stunned into silence. Then pandemonium erupted. Spectators stood on their seats, whooping, gaping in disbelief at the knocked-out champion, cheering long and hard for Carter. The former hoodlum was now a hero. He had cocked a Sunday.

The triumph did more for Carter than prove he could slay a Goliath. It gave his life purpose and legitimacy. The boxing ring became his new universe, a place where his splenetic spirit and brawling soul were not only accepted but celebrated. His enemy couldn’t hide behind a warden’s desk or a police badge. He now stood face-to-face with his rival, and each bout had a moral clarity: the best man won, and if you fight Rubin Carter, you better bring ass to get ass.

After the Nelson Glenn fight, Carter never held an Army weapon again. Mullick cut through the Army’s red tape and transferred Carter to a Special Service detachment for boxers for the 502nd. They lived in their own building, three glorious floors for twenty-five men. The first floor held a vast recreational area, with ping-pong tables and pool tables, as well as a kitchen. The second floor was sectioned off with bathtubs and shower stalls, whirlpools and rubbing tables, while the top floor had secluded sleeping quarters. This was nirvana in the Army.