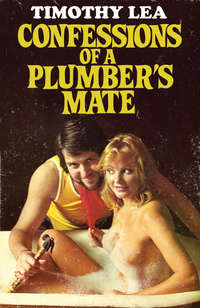

Confessions of a Plumber’s Mate

‘He didn’t wear one, did he?’ says Dad. ‘I thought I hadn’t seen much of him lately. That explains it.’

Before there can be any more explanations, the front doorbell rings. ‘That’ll probably be the food,’ says Rosie. ‘Show them in, Sidney, will you? I’ll help myself to a drink. It’s the only way I’ll get one.’

‘I wouldn’t mind another little drop,’ says Mum, putting down her sherry glass and picking up a tumbler.

‘Me neither,’ says Dad.

I can’t help noticing that Mum and Dad are knocking back the booze like there is a prize for it. I do hope that this is not going to lead to any unpleasantness later in the evening.

As Rosie deals with the drinks, the door opens and a really knock-out bird sails in. She is wearing a long black dress that hangs down from just beneath her knockers and touches the floor, and her blonde barnet flops beguilingly over one eye. Dad registers the newcomer and it is easy to see that he is impressed.

‘Blimey very muchee,’ he says. ‘You no lookee likee Chinese lady.’

Rosie looks embarrassed. ‘This is Imogen Fletcher, father,’ she says.

‘No soundee like Chinese lady,’ says Dad.

‘I no am Chinese lady, that’s why,’ says the bird in a very upper class drawl. ‘My husband and I have lived at Stockwell for three and a half years now. We’re practically natives.’

‘You’re not like most of the natives you see round here,’ says Dad. ‘Do you want a hand with the grub? I hope you don’t expect me to eat with those joss sticks. I have enough trouble with a spoon. I find the bean shoots get stuck between my dentures. Do you have –?’

Listening to Dad is like wanting to cry out when you are having a nightmare. You can see all the terrible things that are happening but when you open your mouth, nothing comes out. Fortunately, Rosie does not have my problems when it comes to basic communication.

‘Really, father!’ she says. ‘How can you be so stupid? Surely it’s obvious that Imogen and Crispin have nothing to do with the meal. They’re guests, like you.’

It occurs to me that Imogen is not a guest like Dad, and Crispin, when he comes into the room bears even less resemblance to my father – or anyone else’s father for that matter. He is wearing a kind of silk tank top with puff shoulders and sleeves and a chiffon scarf that comes down to his knee breeches. These are fastened by a diamanté buckle as are his black shiny shoes. It is a dead cert that he is not a New Zealand rugby player.

He stops in front of Dad and claps his hands together.

‘How quaint!’ he says. ‘I’ve never seen it done better.’

‘Your friends may be able to say the same about you,’ says Dad menacingly. ‘What are you on about?’

‘Look at those clothes, darling,’ pipes Crispin. ‘They’re so authentic, aren’t they? I wonder if his trousers are held up with string?’

‘Crispin’s terribly well known as an interior decorator,’ explains Rosie.

This news does not surprise me. I have no difficulty at all in imagining the creep decorating interiors. What does surprise me is that Rosie should fancy someone like that. It is because he is artistic, I suppose. She always reckons that she is a bit starved in that direction having Sid as a husband.

Crispin is still staring at Dad’s suit. ‘Where did you get it from?’ he croons. ‘Do you have pull at the Salvation Army?’

Actually, I think Crispin is being a bit unkind. Dad’s best suit is no worse than any other old geezer’s clobber. The stains round the front of the trousers aren’t very nice but the half inch of grey woollen underpant protruding above the belt and giving way to the frayed ends of the waistcoat dangling temptingly above it seems to have been with me since childhood. Maybe that is it. I am too used to Dad. Either that, or his cap is creating the wrong impression. I saw Mum trying to take it off him when they came through the front door but he wasn’t having any.

‘And that lovely dress,’ says Mrs Fletcher, turning to Mum. ‘Did you knit it yourself?’

‘No,’ says Mum with a funny half curtsey – I can understand why she does it. Imogen Fletcher does make you think that you are in the presence of royalty – ‘I got it at Marks and Spencers. I get all my stuff there. All my clothes, that is.’

‘They are marvellous, aren’t they?’ says Mrs F brightly. ‘I noticed they had avocados there the other day.’

‘Oh really?’ says Mum. ‘That is nice.’

‘What would you fancy to drink?’ says Sid.

Mrs Fletcher orders and turns to me. ‘You must be young Timothy,’ she says. ‘I’ve heard so much about you.’

‘Nothing too terrible, I hope,’ I simper. Mrs Fletcher is the kind of poised upper-class bird who reduces me to a shapeless, mumbling twit. There are tiny little valleys at the corners of her lovely soft cakehole and when she twitches her lips it is as if somebody has pulled a bit of string tied round my Willy Wonker. I nearly ice my birthday cake.

‘Quite the reverse,’ says the lady. ‘I believe you’ve been a tower of support to Sidders in his many business ventures.’

For a moment, I wonder what she is talking about. Then I get it. She means Sid. The upper classes are always messing about with names, aren’t they? Ronny is acceptable but with Ron you have practically kicked the bucket – or gone beyond the pail, as the nobs say.

‘I’ve done what I can,’ I say. ‘Tell me, how do you know Sid and Rosie?’

Mrs F accepts a drink and gestures me towards the settee. ‘It’s all to do with Crispin,’ she says, draping herself gracefully across the scuffed leather. ‘He had a hand in your sister’s venture.’

I am surprised at her coming out with it just like that but some of these posh bints don’t care what they say. That’s what makes them so exciting. On the surface all pure and untouchable, underneath raring to cop a snatchful of steaming hampton straight between the thighs. What does come as a bit of a shock is that Crispin is a furburger fan. I had reckoned him as being a bit of a ginger on the noisy. Just shows how you can’t make sweeping judgements about people.

‘Yes,’ continues Mrs F. ‘He was in at the start of the boutiques and did all the decor for the wine bars.’

‘Oh,’ I say as it occurs to me that I may have misunderstood the lady. ‘You mean the sawdust and that?’

‘Inspirational, wasn’t it?’ says Mrs Fletcher proudly.

‘Definitely,’ I say. ‘I know that Sid uses a lot of it for the kiddies’ ferrets.’ I see a look of doubt coming into Imogen’s eyes. ‘The sawdust, I mean,’ I say hurriedly.

‘Of yes,’ Mrs Fletcher looks round and then places one of her elegant, beautifully manicured Germans on top of mine. ‘Do you think you could coax a teensy weensy bit more gin into my glass? I’m a rather greedy girl, I’m afraid.’ The way she looks at me when she speaks, I would walk barefoot across a sea of white hot coals to fetch her a Kleenex. I stand up and she touches my jacket. ‘Some ice would be fantastic too.’ She winks at me and I have fallen in love. To think I was really not looking forward to this evening. The best things always happen when you least expect them.

I have just wrenched the stupid bird-motif measuring device off the top of the gin bottle and poured Imogen Fletcher a generous slug when Sid moves to my side.

‘Where’s the ice, Sid?’ I ask.

‘It’s in the – fuck!’ Everybody stops talking and Sid examines the front of his jacket. He had tipped up the gin bottle without looking at it and copped the rebound from the bottom of the glass he was filling. ‘Uxbridge!’ shouts Sid, ‘Just beyond the traffic lights. You can’t miss it.’ The threads of conversation are picked up again and Sid turns to me. ‘Did you do that, you stupid berk?’ he hisses.

‘Sorry, Sid,’ I say. ‘It pours so slow with that thing in it.’

‘That’s the idea, you prat! Just leave things alone.’

‘Just tell me where the ice is,’ I plead.

‘I didn’t get any out – I didn’t have time with you arriving an hour early!’

‘I’ll try the fridge,’ I say.

Mrs Fletcher gives me a melting look that would see off any lump of ice I had in my hand and I sear towards the kitchen. Crispin Fletcher tries to catch my eye as I speed past and, rejected, turns back to Dad. ‘That really is very interesting,’ I hear him say.

‘That’s just some of the stuff we get in,’ says Dad. ‘Then there’s walking sticks and shooting sticks and umbrellas – oh yes, we get a lot of umbrellas. The last time we counted we had –’

I whip into the kitchen and close the door behind me. It does not half have a lot of gadgets. When you look around, you can see that Rosie is doing all right. I don’t reckon that Sid bought too much of this lot. I have just opened the fridge and knocked a tub of cream over three storeys of food when Rosie rushes in.

‘It hasn’t come!’ she storms. ‘Little perishers. They promised it by eight.’

‘Oh, the food,’ I say, cottoning on to what she is rabbiting about. ‘Can’t you give them a ring?’

‘I don’t have the number. I called in on the way home.’

‘They must be in the book,’ I say.

‘I can’t remember the name. You know what they’re like: Hing Pong, Flung Dung – it could be anything.’

‘If you had a classified you could find out from the address.’

‘But I don’t!’ Rosie faces me angrily. ‘What’s the matter with you? Are you an undercover agent for the GPO or something?’

‘Calm yourself,’ I say. ‘We all have our problems. Where’s the ice?’

‘In the top. Oh no!’ Rosie looks inside the fridge. ‘Did you spill that?’

‘No, it was like that when I opened it.’

‘It must have been Sid,’ snarls Rosie. ‘I’ll kill him one of these days!’

‘You mustn’t be too hard on him,’ I say, holding the ice tray under the hot tap. ‘He’s had a lot on his mind, lately.’

‘A lot on it and nothing in it,’ spits Rosie. ‘I’ll have to give them something to tide them over. Don’t let Dad have another drink what ever you do. He’s pissed already.’ She puts a jar marked ‘cheese’ on the table as I look around for something to put the ice in. ‘I’ll give them a quick fondue.’

‘You’ll what?!’ I say.

‘Give them a fondue – a cheese dip.’

‘I thought you said you’d give them a quick fondle!’

I think the misunderstanding is quite funny but Rosie seems to have lost whatever sense of humour she once had. She accuses me of getting in her way and pushes me to one side while she puts on a saucepan. It is all I can do to tip the ice into a jar before she drives me out of the kitchen. When I get back to the lounge, Imogen is sitting where she was but her lovely mince pies shelter a look of reproach.

‘I thought you’d forgotten about me,’ she says.

‘I don’t think I could ever forget about you,’ I say.

‘How nice.’ Her lips twitch again like they did last summer and I feel percy preparing for a game of ‘Launch My Zeppelin’. ‘You got the ice, did you? I’m sorry to be such a terrible nuisance.’

I make a few mumbling noises and hand over her glass. When she looks at me like that it is difficult to think of things to say. I take the top off the jar and hold it out to her. It seems better mannered to let her help herself rather than cop a mittful of my germs. If I had thought about it I could have brought a pair of tongs but it is too late now. She is still holding my glance and I wonder if she knows what is passing through my mind – I hope her husband doesn’t. Possibly, she is feeling something of what I feel. Beautiful, mature women of the world do fall passionately in love with simple working class lads like me. Half the plays you turn over to on BBC2 for the juicy bits are about it.

Mrs Fletcher sticks her mitt in the jar and – ‘Oh!’ We both look down to see that her delicate digits are grasping what looks like a cube of parmesan cheese. Oh my gawd! In my confusion I must have tipped the ice cubes into the cheese jar. ‘How frightfully original,’ says Mrs F.

Rosie appears at my side. ‘You didn’t touch the –’ She takes a butcher’s at the object between Imogen’s fingers and squeaks.

‘I think, if you don’t mind –’ says the love of my life.

‘I’m very sorry,’ I say. ‘I didn’t mean –’

Rosie snatches the jar out of my hand. ‘Are you mad?!’ she says. ‘Are you stark raving mad?’

Before I can say any more, the front door bell rings. ‘It must be the nosh – I mean, food,’ I say. ‘I’ll let them in.’

As I head for the door, I hear Rosie explaining that both Sid and I have been under a lot of strain lately. It is noticeable that when she talks to the Fletchers her voice is a lot more refined than it is when she is parleying to the family.

‘– a hundred and forty-five with broken spokes. Of course, with them it’s touch and go as to whether they were lost or abandoned. That’s something only experience will tell you –’ Dad’s voice is still droning on as I open the front door.

‘Solly about delay. Go to wong address. Very tlying.’ The little bloke with the pile of containers is behind me before he has finished his sentence. I look out into the street in case there is any one else but there is only a large black cat running as fast as its legs will carry it. ‘Where you want?’

‘Well, I think everybody’s quite hungry now,’ says Rosie looking at Dad anxiously. ‘Can you lay it out on the table, please?’

‘Chinese food? How lovely!’ Imogen Fletcher drops the cheese-covered ice cube into an ashtray and rises to her feet.

‘Those cats were Kung Fu fighting,’ croons Dad. ‘I don’t reckon it myself, you know. I mean, look at him. He doesn’t come up to my chest.’

‘Neither does anyone else if they got any sense,’ says Mum. ‘Come on, Walter. Get a grip on yourself.’

The Chinese bloke is laying out lots of little cardboard boxes full of grub and taking no notice of Dad.

‘You hear what I say, Chinky Chops?’ goads Dad. ‘Show us a bit of the old martial arts. Bamboo stalk that bend in wind no support mighty pagoda. You savvy words of Oriental wisdom?’

‘You savvy punch up throat?’ says the small Chinese gentleman.

‘Stop it, Dad!’ says Mum. ‘Can’t you see you’re embarrassing everybody?’

Dad starts swaying and bobbing – he has been swaying for most of the evening. ‘Those cats were Kung Fu fighting,’ he chants. ‘Oh, it was most exciting – Come on, Ping Ling. Show us your muscles!’

The Chinaman places both hands together and bows towards Sid. ‘Food laid out,’ he says.

‘You know what you are?’ says Dad. ‘You’re yellow! All you Chinks are the same. You can’t even get a proper Chinaman to play one of you. That bloke in Kung Fu, he’s not Chinese. They pull his eyes back with sellotape.’ WHAM! CRASH! BANG! Dad turns a couple of somersaults – it may have been three, it happens so fast – and lands in an untidy heap on the settee.

The Chinaman gives Sid another bow. ‘Honourable gentleman laid out,’ he says.

‘Do something!’ screams Dad, scrambling to his feet and trying to hide behind Mum. ‘Don’t let him get away with it. Coming in here and assaulting innocent people. Ring for the police!’

‘Do shut up, Walter,’ says Mum. ‘You had it coming to you.’

‘Yes, Dad,’ says Sid. ‘Belt up!’

The Chinaman goes out and Dad immediately advances to the drinks tray and empties the remains of a bottle of brandy into a tumbler. ‘Soon saw him off, didn’t I?’ he says. ‘Didn’t take him long to see which way the wind was blowing. He could see what was going to happen – one carrotty chop on a vital nerve point and – pouf!’ – Crispin looks up sharply. ‘All the way back to Gerrard Street in a wheelbarrow.’

‘Talking of carrotty chops,’ says Sid, indicating the nosh. ‘We’d better get stuck into this lot before it gets cold.’

In fact, it is cold. And there is not much worse than cold Chinese food – though this stuff would probably run it close when it was hot. Crispin and Imogen send out a series of polite squeaks but Dad is blunt in his attitude to the fare provided. ‘I don’t mind the vinegar,’ he says. ‘That’s got more taste than the rest of it put together. I reckon it’s why they’re so small, these Chinks. You can’t build a man up on this, can you? It’s not like the roast beef of old England.’

‘The Roast Beef of Old England doesn’t seem to have got us very far at the moment, does it?’ says Crispin, carefully picking a bean shoot off his blouse.

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’ says Dad. ‘Don’t you fancy this country, then? Are you one of those knockers who’s always saying we’re not the greatest nation living on Earth?’

‘We will be living on earth if we go on at this rate,’ says Crispin.

‘Oh yes, darling. Very good,’ says the lovely Imogen.

‘What do you mean, very good?!’ says Dad ferociously. ‘That’s not very good, that’s bleeding awful! Are you a foreigner? Come over here to load yourself up with free specs and dentures on the National Health?!’

Oh dear. I can see that the demon liquor has once again unhinged Dad’s feeble mind. He always becomes unpleasant when he has had a few.

‘Dad –!’ says Sid.

‘Not so much of the Dad, sonny! Your relationship to me is one of marriage, not blood. You never sprung from my loins.’

‘He would if he had to get anywhere near them,’ sniffs Mum.

‘You shut your face!’ says Dad.

‘Really!’ bristles Imogen. ‘I think you’re the most unpleasant old man I’ve ever met!’

‘That’s because I’m a patriot!’ rants Dad. ‘Because I won’t stand to see my country run down by shameless hussies who want to show off their tits and inflame men’s natural appetites! If you’re so proud of them, let’s all see them!’ So saying, he lunges for the front of Imogen’s dress, loses his footing, and collapses on the imitation sheepskin rug.

‘That’s it!’ snaps Rosie. ‘I want him out of my house! I don’t care if he is my father. I never want to see him again!’

Mum stops hitting Dad over the bonce with her shoe. ‘What do you mean if? Of course he’s your father! You mind what you’re saying, my girl!’

‘Out!’ screams Rosie. ‘Out!’

Imogen Fletcher rises to her feet, her hand draped elegantly against her forehead. ‘Please don’t disturb your father,’ she says. ‘I think it’s better if I leave. I’m not feeling very well. Crispin –’

‘But you can’t leave yet,’ says Sid. ‘You’ve hardly touched your sweet and sour pork. Anyway, there’s something I want to talk to you both about. It’s been at the back of my mind for a long time.’

‘Well, I think if – er, Imogen isn’t feeling herself –’

‘I wouldn’t put it past her,’ says Dad from the floor. ‘Feeling herself, I mean.’

‘Shut up!’ Sid kicks Dad in the stomach and it is obvious that the evening is on the verge of boiling over into unpleasantness. ‘You stay, Crispin,’ begs Sid. ‘If Imogen doesn’t feel up to it, Timmy can drive her home. It won’t take a minute. I’ve got an idea I want to talk to you about.’

‘Er – well?’ Crispin looks at Imogen and I can see that he is about as keen to stay as he would be to substitute his cock for a piece of cheese in a rat trap. To my surprise, Imogen seems prepared to look upon the idea with less than total disfavour.

‘I’m certain Timothy doesn’t want to take me home,’ she says – is it my imagination or is that a pout at the corner of that delectable mouth?

‘It would be a pleasure,’ I say. ‘I mean – I wouldn’t mind at all.’ I tone my response down when I see the way Crispin is looking at me. Wary might be one way of describing it.

‘I think, maybe I’d better –’

‘That’s settled then,’ says Sid breezily. ‘I hope you feel better soon, Imogen. I’m sorry about my father-in-law. He becomes prone to these bouts of over-tiredness.’

There is a lot more ‘lovely evening!’ and ‘don’t mention it’ while Rosie fetches Imogen’s coat. Crispin has grudgingly given me his car keys and is staring at the jumbo-sized brandy Sid has just shoved in his mitt. ‘The reverse is up and away from you,’ he says.

‘Your wife knows the – yes, of course, she must do,’ I say, glad that I have prevented myself from asking if Imogen knows the way to her own home.

‘I’m ready,’ she calls to me from the front door. Her handbag clicks shut like a trap closing on its prey and she delivers a minute flare of the nostrils as she catches my eye. ‘Goodnight, Crispin,’ she says. ‘I’m going to take one of my pills, so I won’t be awake when you get home.’ Crispin says something sympathetic and blows her a kiss. They don’t have a proper Swiss Miss.

‘How do you feel?’ I say, once we are in the car and I am trying to find out how the lights work.

‘Tense,’ she says. She feels in her bag and brings out a packet of fags. ‘Do you use these?’

‘No,’ I say. I am wondering whether to do any more apologizing for the family. In the circumstances, it seems best to leave the subject alone. It could sound a bit like a German apologizing for Hitler. ‘Tell me where you want me to go, will you?’

‘Down the end of the street and turn left. It’s very near. I could have walked.’

‘Better not to, these days.’ I say in my best Dixon of Dock Green voice. ‘You might bump into a spot of bother.’

‘You mean, I might be raped?’ She drags in a lungful of smoke and blows it out so hard that I expect it to splinter the windscreen. ‘I should be so lucky.’

‘There’s one or two nutcases about,’ I say.

‘Lead me to them!’ Mrs Fletcher grits her teeth and rakes her finger nails down my thigh. I manage to keep the car off the pavement, but only just. ‘Poor Timothy,’ says my volatile passenger. ‘You must think I’m mad.’

‘Of course, I don’t,’ I say soothingly. ‘You’re just a bit unsettled, that’s all. The cheese on the ice-cubes and all that.’

‘You think it’s giving me nightmares?’ Imogen laughs. ‘Cheese is supposed to give you mightmares, isn’t it?’

‘You didn’t eat any, did you?’ I say soothingly.

Lovely Imogen Fletcher brushes some hair from her eye. ‘It’s often the things you don’t have that give the most trouble, isn’t it?’

‘I suppose it is,’ I say. I don’t have to get out my crystal balls to see that there is something troubling the lady. Something apart from Dad and the rest of the aggrochat. ‘Your family wear their hearts on their sleeves, don’t they?’ She gives a short laugh. ‘That father of yours practically wears his parts on his sleeve!’

‘I’m sorry,’ I say. ‘I –’

Imogen touches my sleeve. ‘Turn right at the level crossing and it’s the third house on the right. Don’t apologise for your father. At least he comes out with what he thinks. Crispin and I are less honest.’

I take the car round the corner and pull up outside the third house. It is half a large semi-detached, painted white. I notice that they have new dustbins. ‘Here we are,’ I say.

Imogen pulls her coat across her Manchesters. ‘Come in and have a drink,’ she says. ‘A coffee, something like that.’ The way she says it, she sounds as if she means it. ‘You weren’t particularly enjoying the party, were you?’

‘I was enjoying being with you.’

Imogen waves a hand like a conjuror producing a handkerchief from her sleeve. ‘If you come in, you’ll continue to be with me.’

I hesitate for a moment while I think what her old man is going to say. Is he going to cut up rough if I don’t show up in a couple of minutes? Sid and Rosie haven’t exactly been responsible for the party of the year, so far. Am I going to put the kibosh on it even further?

‘Nobody will notice if you’re away for a few minutes.’ She is right, of course. When you’re pissed – and everybody at Rosie’s was pretty pissed – people can disappear for hours and it seems like minutes. I remember when Sid had it off with Gabriella Duke at Sandy Ponder’s party. I thought he’s only just gone into the karsi, yet, when they broke the door down they were both starkers and she was – it doesn’t really matter what she was doing. That has nothing to do with the time element. It didn’t half surprise me, though. Mainly because I was younger, I suppose.

‘Are you coming?’ Love Goddess is getting out of the car and tilting her flawless nut in my direction. It’s meeting a bird like this that makes me wish I’d been to Oxford University. It may seem a funny thing to come out with but it’s true. It’s all a question of communication. You have to have the same terms of reference if you are going to sustain a relationship. I don’t mean having money and talking posh. I mean approaching things in the same way. Having the same attitude of mind. If you don’t have that in common then you’re never going to get much further than humping the sack together. It doesn’t normally worry me overmuch. Only sometimes. Very rarely. Occasionally.