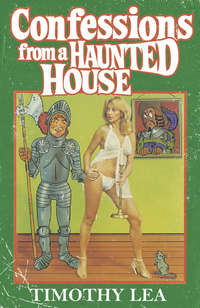

Confessions from a Haunted House

‘Goodbye?’ cried Mum. Where are you going?’

‘My own way,’ said Sid. ‘From this moment on I’m ploughing a lonely furrow.’

‘Farming?’ said Dad. ‘I’ve always thought you had the fingernails for it. But where are you going to farm around here? You’ll have to move out to Croydon or somewhere like that.’

‘I was employing a figure of speech,’ said Sid bitterly. ‘About all I can afford to employ at the moment thanks to laughing boy here.’

‘But what about the business?’ asked Mum. ‘“Emergency Disasters”.’

‘The Noglea Emergency Service,’ hissed Sid through clenched teeth. ‘That is now folded up.’ He laughed hollowly. ‘Not unlike the front half of my mini van.’

I did not say anything. This was another subject that Sid was touchy about. When the flat exploded, the cooker and the fridge went out of the window and landed on the van. It was unfortunate but none of us was spared discomfort. I had to walk home after we had dropped Sid off at the hospital.

‘Are you trying to say that you and Timmy aren’t going to work together any more?’ said Mum.

‘That’s exactly what I’m trying to say,’ said Sid. ‘My legendary patience has finally disappeared up the spout. I have lost count of the wonderful career opportunities on which the dead hand of Lea has put the mockers. From now on we’re finished. F–I–N–’ he started to spell it out and then came to a halt. His spelling was no better than Mum’s.

‘N–’ prompted Mum.

‘There’s only one N in “finish”, you stupid old moo,’ Dad jeered.

‘Blimey, you don’t know nothing about the English Language, do you?’

‘F–I– We’re through!’ shouted Sid.

‘T–H–R–E–W,’ added Mum triumphantly.

At that moment the front door bell rang and Mum went to look through the lace curtains in the front room. Nobody casually chucks their front door open in Scraggs Lane. There might be some suspicious character lurking there. Like a copper.

I must say that Sid’s words took me back a bit. We had been through a lot together – and I am not just talking about birds. Of course we had had our ups and downs – and I am not just talking about birds – but when all was said and done and the water had been passed under the bridge – or against the police station wall – I thought we had a bond between us stronger than anything I would have cared to put into words without a packet of Kleenex handy. Now it seemed that all this was over. The idea took a bit of getting used to. I was so overcome that I remember helping myself to a second cup of tea. Only a warning glance from Dad stopped me from drinking it.

Mum came in holding an airmail letter. ‘It’s from America.’

‘If they want you to support the dollar, they’ve come to the wrong bloke, eh Sid?’ Dad laughed heartily at his little joke while Sid squeezed his teacup so hard that the handle came off.

‘Why didn’t they shove it through the letter box?’ said Dad.

‘Because it was under-stamped,’ Mum explained. ‘The address was wrong as well. It’s been all over the place.’

‘Must be from your sister then,’ said Dad. ‘Mean and stupid. She must have got married again.’

‘She’s only got married twice,’ snapped Mum. ‘That’s nothing in America.’ Mum’s sister Eileen was a G.I. bride. She went to live in Washington at the end of the war – the one that finished in 1945 – and had never been back. Normally we got a Christmas card with news flowing over onto the back, but this was not Christmas.

‘Open it up then,’ said Dad. ‘Let’s see what the old bag’s been up to. Fancy marrying again at her age. Its disgusting.’

‘You don’t know she’s getting married again,’ said Mum, rummaging through her bag for her spectacles. ‘When she last wrote she was very happy with Dwight.’

‘Dwight,’ said Dad, puckering up his mouth. ‘Fancy being called Dwight. It sounds like a plant disease.’

Mum tore the envelope open and made a ‘tcch’ noise. ‘Ooh. This has taken a long time getting here.’ She read on. ‘One of the children is coming over. Harper. Do you remember a Harper, Walter?’

‘No,’ said Dad. ‘Must be a grandchild. What diabolical names they do lumber their kiddies with. Poor little boy.’

I did not say anything. I remembered how they used to take the piss out of me at school because I was called Timothy.

Mum was still reading the letter. ‘She asks if we can put the child up.’

‘Typical!’ grumbled Dad. ‘I don’t know why we don’t turn this place into a guest house and have done with it.’

‘Don’t be unreasonable, Walter,’ said Mum. ‘It’s the first thing she’s ever asked us to do except send the Marmite – Oh no!’

‘What is it? Does she want some more Marmite? It’s out of the question. The postage on the—’

‘The child is arriving today!’ Mum’s voice was panic-striken. ‘Ten o’clock at Heathrow Airport! What are we going to do?’

‘Stupid Twits!’ said Dad. ‘You mean they sent the kiddy off without waiting for a reply?’

‘Eileen says “If everything’s all right, don’t bother to reply”.’

‘I always knew she was a daft ha’p’worth!’

‘That’s neither here nor there,’ said Mum. ‘It’s the child we’ve got to think about. How long will it take to get to Heathrow?’

‘At least an hour unless we get a taxi,’ I chipped in.

‘A taxi?’ I might have asked Dad to fill a petrol drum with his own blood. He turned to Sid. ‘What about your van?’

‘What about my van!!?’ Now Sid started to shout. ‘It was a write-off, wasn’t it?’

‘Oh yes,’ I said. ‘Did the insurance pay up?’

Sid looked uncomfortable. ‘Yes, well – er in a manner of speaking, yes. They made a ridiculous offer that I was eventually compelled to accept. Muggins lost out as usual.’ Sid stood up. ‘Right, that’s it. I’ve said what I wanted to say. I will now leave you to grapple with this latest self-inflicted disaster. No doubt we will see each other at Christmas. I don’t know which one but—’

‘What have you done with the insurance money, Sid?’ I asked softly. ‘I mean, I was contributing to the down payments on that van, wasn’t I? It was one of the fringe benefits I was getting instead of a salary.’

At this point Sid began to look uncomfortable and Mum turned her beady eye on him. ‘That old car outside the front door. Who does that belong to?’

‘That is my car,’ said Sid, with a firmness that was almost vicious. ‘Paid for with my money. Taxed and insured with my money – or it will be when I can get around to it.’

‘Where’s my money then?’ I said.

Mum held up a restraining hand. ‘You can talk about that later. Right now I think the least you can do is go and meet little Harper. We can’t have him wandering round London Airport by himself.’

Sid’s face screwed up like an old sock. ‘Lumbered to the bitter end,’ he groaned. ‘I should have known better than to come round here. Right—!’ He banged his fist down on the table and the marmalade spoon performed a couple of somersaults and landed up in his breast pocket. I refrained from applauding. ‘Let it be known that this is the last service that I will perform for you lot. Once I have delivered the infant Harper into your clutches I will be leaving this house for ever. The fluff from your sitting-room carpet will never fill my turn-ups again.’ So saying, he stood up smartly pausing only to crack his knee on the underside of the table.

He was still worked up as we sped down the M4 in what I read on the bonnet to be an Armstrong Siddeley. The name was familiar to me. Like Boadicea or the Ancient Bede. ‘Make no mistake,’ he said. ‘I meant what I said back there. This is the parting of the ways.’

‘I’m sorry, Sid,’ I blurted. ‘I’m sorry for everything. Are you really serious?’ I don’t know why I was going on like this because I had often thought I needed my brain examined to keep tagging along with Sid’s disastrous schemes. However, when it came to the crunch, there I was, grovelling with the best of them.

‘I’ve never been more serious in my life,’ said Sid. An edgy hand snaked into the glove compartment and emerged with a fag which he shoved between his lips. Eager to show willing, I snatched out the cigarette lighter and then found that it was one of the knobs on the walnut fascia. I quickly tossed it aside before Sid could say anything and got hold of the right article. With exquisite care I applied it to the end of Sid’s fag and waited for the maestro to do the necessary. There was a squeal of brakes in front of us and Sid stepped on the anchors. When I looked back at the ciggy it was concertinaed against the noble lips with the lighter nearly inside Sid’s cakehole. His mince pies were peering down towards it like they might tilt out of his nut. I waited a few seconds and then realized that Sid had lost interest in this particular cigarette. ‘You might as well throw it away,’ he said slowly and bitterly. I don’t know what came over me then. I knew he meant the cigarette but it was the lighter that I chucked out of the window. I emitted a nervous shriek when I realized what I had done and promptly pressed the remains of the fag into the hole where the lighter lived. Sid looked at me suspiciously but did not notice what had happened.

We whipped round a roundabout and entered the long tunnel that leads to the airport. ‘Terminal Three,’ I said helpfully.

‘I know, I know,’ snapped Sid. ‘I’ve got to park, haven’t I? Keep your feet on the mats. This car represents all I have left in the world. I want to keep it nice.’ A thought occurred to him and his brow started to unroll over his eyes like a shop blind. ‘If that horrible little kid starts smearing bubble gum all over the upholstery he’ll get to Clapham as a jigsaw puzzle.’

I did not say anything because I knew that there was no point in talking to Sid when he was in one of his moods. You just had to wait for him to become himself again – not that that was worth hanging around for if there was anything good on the telly.

We went through the traffic lights, past the filling station and up a ramp. The entrance to the car park was via a slip road on the left. Sid stopped at the white pole and a geezer wearing a Sikh’s turban stuck his head out of the kiosk and started addressing Sid in Hindustani. It took me a moment to understand what was happening and then I realized that he had mistaken Sid’s bandage for a turban. Laugh? I thought I’d never stop. Until I saw Sid looking at me. Then I stopped immediately. Sid is tragically slow to see a joke against himself.

We parked the car in silence and not a word was spoken until we reached the arrivals board. Sid looked up at the flashing lights and groaned. ‘The flight’s in. Typical. The day we arrive there has to be a tail wind across the Atlantic. Normally they’d be stacking over Shannon.’

I did not ask him what he was talking about but looked down the hall towards the ‘Arrivals’ gate. Standing with his back to us was a small figure wearing a stetson and high-heeled cowboy boots. Sid followed my eyes and his lip began to curl. ‘That must be him,’ he said. ‘Blimey, what a twit. The kids down Scraggs Lane aren’t half going to give him a going over. I reckon even Jason could handle him.’

Jason Noggett was my brother-in-law’s first-born and as about as handy with his fists as Dame Edith Summerskill. Sadistic, mean and untrustworthy – but no exponent of the noble art.

Sid loped off and I was about to follow him when I glanced through the glass wall into the baggage claim area. Imagine my surprise – go on, I dare you – when my peepers collided with a large carpet bag that had just been lifted off the conveyor belt. On its side in large italic letters was woven the word ‘Harper’. My eyes panned up from the bag and – wow! – what a favour they did themselves. A bird not unlike Farrah Fawcett Thingamybobs was shaking her blonde curls and gazing hopefully for sight of more baggage. I did no more than establish that she was about nineteen years old and definitely a looker of the first magnitude before turning back to grab Sid. Clearly there had been a misunderstanding or an amazing coincidence. ‘Sid—’ My voice struck him firmly between the ear holes but he did not stop. Before I could get close to him, he had sailed up to the American kid and grabbed it by the arm.

‘OK Hopalong Cassidy. Where’s your bag?’

At that point, both Sid and I got a big surprise. The kid turned round to reveal that it had a goatee beard and a moustache. It was obviously very old for its age. Say, about fifty. Sid’s surprise was in fact rather larger than mine because the bloke did not kick me in the instep. Sid let out an agonized shriek and flung back his fist to let one go. I could tell immediately that this was not a good idea. Immediately I saw the geezer standing behind Sid. He was about seven feet tall and made Frankenstein’s monster look like Petula Clark. His great mitt slammed down on Sid’s wrist and within seconds my brother-in-law’s feet were tap dancing eighteen inches off the ground whilst he got a close-up view of the bloke’s fillings.

‘Sid,’ I said, reaching up and tapping him on the back. ‘That’s not him. There’s been a mistake.’ I never found out if Sid was grateful for the information because the little guy spat out a couple of words and the big one let go of what used to be Sid’s lapels. There was a noise like a bomb dropping and Sid landed in an untidy heap on the floor. Colonel Saunders and his mate strode off. ‘Over here,’ I said, eager to get away from the scene of this embarrassing incident. ‘I think that’s Harper.’ I pointed through the sliding doors where the carpet bag had now been joined by a vanity case. Sid shook his head and took in the sight. ‘You fool,’ he snapped. ‘Why didn’t you tell me before? Thank gawd I won’t have to put up with your snivelling incompetence much longer.’ So saying he stepped forward briskly through the sliding doors that had opened to let out a customs official. They promptly closed on his shoulders and for one interesting moment I thought they were going to meet in the middle of his windpipe. But they opened again and I slipped through as about half a dozen blokes in dark blue suits converged on Sid to ask what he thought he was doing. The bird with the carpet bag turned to see what all the commotion was about and I was swiftly at her side.

‘Hi,’ I said in my best transatlantic manner. ‘Is your name Harper?’

‘It sure is,’ she said, turning on a big hundred-watt smile. ‘You’re not Timmy, are you?’

‘Every throbbing corpuscle.’ The sound of heavy breathing alerted me to the presence of my brother-in-law. ‘And this is Sid.’

‘Gee. I never expected your father to come along as well, I feel real honoured.’

I winced on Sid’s behalf as he took a deep breath. ‘Don’t let my mature man-of-the-world suavity confuse you, Harper,’ he said through gritted teeth. My only relationship with Timothy is thankfully one of marriage.’

‘You’re married?’ said Harper brightly. ‘Gee, England is so liberated these days.’

‘He’s married to my sister Rosie,’ I explained quickly.

‘Oh of course. Sidney Noggett. I’ve seen you on the Christmas cards.’ She made Sid sound like a robin. ‘You’re Timmy’s partner, aren’t you?’

‘Was’, said Sid firmly. ‘All that is behind me. Once I deliver you safely to Mrs Lea I will never be darkening their bath towels again. I could go on and explain why, but the details are probably too harrowing for a young girl raised in the colonies.’ I could tell from all the old bunny that Sid was quite impressed with our Harper but his desire to get shot of me was too strong to be set aside. It was all rather hurtful really.

‘I hope it all works out for the best for the both of you,’ said Harper winsomely. ‘Say Sid, would it be awful inconvenient if we passed through the city of London on the way to the house? I’m supposed to see a solicitor very urgently. That’s really why I’m here.’

I could see Sid’s mug settling in to an unhelpful expression so I stepped in quickly. ‘Of course not, Harper. No trouble at all. Are these all your bags?’

I ignored Sid’s nasty frown and followed her pointing arm.

‘Just that one on the top. I’m afraid it’s a little difficult to reach.’

‘The big one?’ I asked.

‘That’s right.’ It was about the size of a cabin trunk yet having the shape of a folded mattress secured by straps. It was balanced on top of a lot of other stuff as if the baggage men had been playing sand castles. Eager to prove that the spirit of English chivalry was not dead I sprang onto the conveyor belt. ‘OK I’ll get it.’

I suppose, in a way, I was right. I did get it. Right in the mush. Hardly had I started grappling with the pile of bags than some thoughtless sod tried to drag his golf clubs out from underneath me and brought the whole lot down. For a few seconds I performed a grape-treading motion whilst staggering backwards under the weight of Harper’s enormous case. Then I collapsed and was swept down the opening where the conveyor belt re-loops. I caught a glimpse of Sid turning round to look for me and then he was snatched from view by the rubber flaps. It was a horrible experience. I can think of a million better ways of spending Christmas. Hardly had I wriggled clear of the golf clubs than another ton of luggage showered down on me from out of the darkness. Bits and pieces of things were sticking into me from all angles. I felt like a new temp at the office Christmas party. Not only that, but as if I had been taken back to my childhood. It was like being on the magic train at Arding and Hobbs which took you to Father Christmas’s grotto. Round the bend I went and there at the end of the tunnel I could see light. Still struggling, I copped a twelve-inch strip of rubber in the cakehole and emerged to find not Father Christmas but Sid. The expression on his face made previous attempts at depicting loathing seem almost half-hearted. ‘You—!’ he began.

He did not have time to finish because an elderly gent in a checked suit elbowed him aside and attempted to retrieve his golf clubs. Normally he would have had my blessing but on this occasion most of the clubs were wedged up my trouser leg – head first. I found out the latter bit when Colonel Blimp gave a vicious wrench which achieved a hole in one – a hole in one of my trouser legs.

‘Where are my balls!?’ he kept shouting. I felt like asking the same question but was prevented by the fact that I was still screaming in agony. The conveyor belt stopped and Sid hauled me off.

As usual he was a tower of support. ‘You stupid twit!’ he hissed, blushing scarlet. ‘Why do you always have to make an exhibition of yourself? I can’t stand the humiliation.’

I stood up and four golf balls rolled out of my trouser legs – two from each side. Colonel Blimp fell on them greedily.

Sid was so worked up that he actually carried one of the bags until we were through customs. Then it was back to me and a tight-lipped silence ensued as we walked back across the ramp to the car park. They walked, I staggered. It was strange but, looking back, I think that that is when I first had the sensation of foreboding. It was not just that Sid’s face was black as the clouds looming overhead but something more. Something indefinable. The car park was cold and gloomy and a sneaky wind was chasing an old fag packet amongst the concrete pillars. There was nobody to be seen and yet I had the feeling that we were being watched. We came to an intersection and I turned my head to look up one of the aisles of parked cars. Just for a second, a figure was framed in the square of light at the end of the row. Then it disappeared. Maybe I am imagining all this because of what happened later but I don’t think so.

After three wrong turnings we found the car and I saw Sid looking towards Harper expectantly. He obviously reckoned that she was going to be impressed with his new toy. ‘Is this your automobile, Sid?’ she asked. ‘Gee. I never knew you were in the antique business.’ Sid’s face dropped a couple of miles.

‘This is a British automobile, Harper,’ he said sternly, really spelling it out. ‘Not one of your blooming great American mouth organs on wheels. We call them cars, as well.’

Harper seemed quite unconcerned. ‘I suppose it is kinda cute,’ she said, after reflection. ‘Back in the States we have something about twice the size of this we call a compact.’

The boot was locked so I put the bags down and went to Sid for the key. He was still trying to sell Harper on the car. ‘This model was the pride of the range, you know. There were people crying outside the factory when they brought in the new version.’

‘Yes,’ I said smartly. ‘All the people who had bought the old one.’ Harper laughed agreeably at my little sally but I could see that it had not gone down too well with Sid. ‘Put the bags in the boot!’ he snapped.

‘The boot?’ said Harper, looking at my feet.

‘He means the trunk,’ I explained.

‘I mean the boot,’ snarled Sid. ‘Harper is in England now. Home of the English language. Elephants have trunks, cars have boots!’ Harper and I exchanged a glance and I went back to the baggage. It was strange but I could have sworn that I had left the vanity case on top of the large bag. Now it was on the ground. I did not think much about it at the time. Later, I did.

The boot was not big enough for all the baggage so I took the vanity case in the back with me. Harper was in the front with Sid. We handed over a few rupees to Sid’s mate and were soon heading for Harper’s first taste of British driving conditions: the traffic jam into London that starts shortly after you leave the airport. Harper looked at Sid’s nut and I realized with a sinking heart that she was about to ask the inevitable question. ‘What did you do to your head, Sid?’

‘I didn’t do anything to it. He did.’ He nodded at me over his shoulder and I smiled winsomely. This was obviously the moment for a change of subject.

‘What does the solicitor want to see you about, Harper?’ I asked.

Her big blue eyes sparkled with excitement. ‘I don’t really know anything yet. It’s something to do with the English branch of the family. I’ve never met any of them. The Deneuves who live near Dartmoor. Do you know them?’

‘I know Dartmoor,’ I said. It might have been my imagination but I thought I saw Sid’s shoulders flinch. Rumour had it that a not too distant relation in the Noggett family did a stretch on the moor for robbing a bank. One of the last brushes with money that the family ever had. ‘Harper, there’s one thing I don’t understand,’ I continued. ‘Are you saying that your name is Deneuve? I thought Aunty Eileen had married somebody called Eikelberger.’

‘It’s kinda complicated,’ replied Harper, giving me the undivided attention of her melting mince pies. ‘Before Eileen married Dwight Eikelberger she was married to my father. I was his child by a previous marriage. Mom died when I was very young. When poor pop died I was the only Deneuve left.’

‘So we’re not really related at all,’ I mused, relishing the good news. ‘There’d be nothing to prevent us getting married.’

Sid groaned. ‘Only the fact that you’ve only known each other for ten minutes.’ He shoved an irritable hand into the glove compartment and fed himself a fag. A fresh feeling of unease held me in its grip. Now Sid was going to find out about the lighter. I fiddled for my own lighter – but too late. Sid pressed his fingers against the spot where he expected to find the lighter and then into the hole. As he looked down, puzzled, there was a little flash and he tore his hand away with a piercing scream. It quite made me jump, it did. Not as high as Sid though. His bandaged nut made a dent in the roof of the car. Poor old sod. With anyone else you would have felt sorry for him. After that the journey continued with a lot more silence and Harper trying to find a landmark to take a photograph of. Not easy when about the only building of merit is where Beechams make their little pills. We were approaching Hammersmith when Sid deigned to speak.

‘Where’s this address you want to go to, Harper?’

‘Oh yeah.’ She turned to me. ‘It’s in the letter just inside my vanity case. Somewhere near a saloon called Gray’s Inn. Can you get it out, Timmy?’

‘Right away.’ Ever eager to oblige, I popped the case up on my lap and flicked open the clips. To my surprise I was not looking at little feminine goodies but an alarm clock strapped to a couple of sticks of rock. Where they came from it was difficult to say because there was no lettering running through the candy. I glanced at the time on the clock. One minute to twelve. It bore no relation to the real time. ‘You’d better reset your travelling clock now you’re in England,’ I said.